Back to Art & Object

7 Examples of Edward Curtis's Photographic Genius

7 Examples of Edward Curtis's Photographic Genius

Photogravure - An Oasis in the Badlands - Sioux

- Artist Edward Curtis

- Date 1905

- Dimensions 45 x 53 in

Photogravure is an expensive and time-consuming method of producing fine photographic prints. It was known as the “king of printing processes” because of its ability to consistently produce rich, finely detailed prints, which made it ideal for Curtis’ forty volume magnum opus The North American Indian. Approximately 98% of all surviving Curtis prints are photogravures because Curtis chose photogravure for the prints needed for his sets of books. Each set was illustrated by over 2,000 images, all printed in the photogravure process.

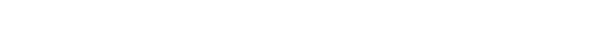

Photo Courtesy : Christopher Cardozo Fine ArtGoldtone - Canyon de Chelly

- Artist Edward Curtis

- Date 1904

- Dimensions 45 x 53 in

Curtis pioneered and popularized the goldtone process (also known as “Curt-tone” or “oro-tone”). Goldtones are printed directly on glass and backed with a gold liquid wash. This gives them extraordinary luminosity and three-dimensionality. It was Curtis’ favorite process and he is acknowledged as the foremost creator of goldtones. Goldtones comprise less than 1% of Curtis’ surviving photographs and are prized by many collectors. Each goldtone was sold with an Arts and Crafts influenced hand-made frame.

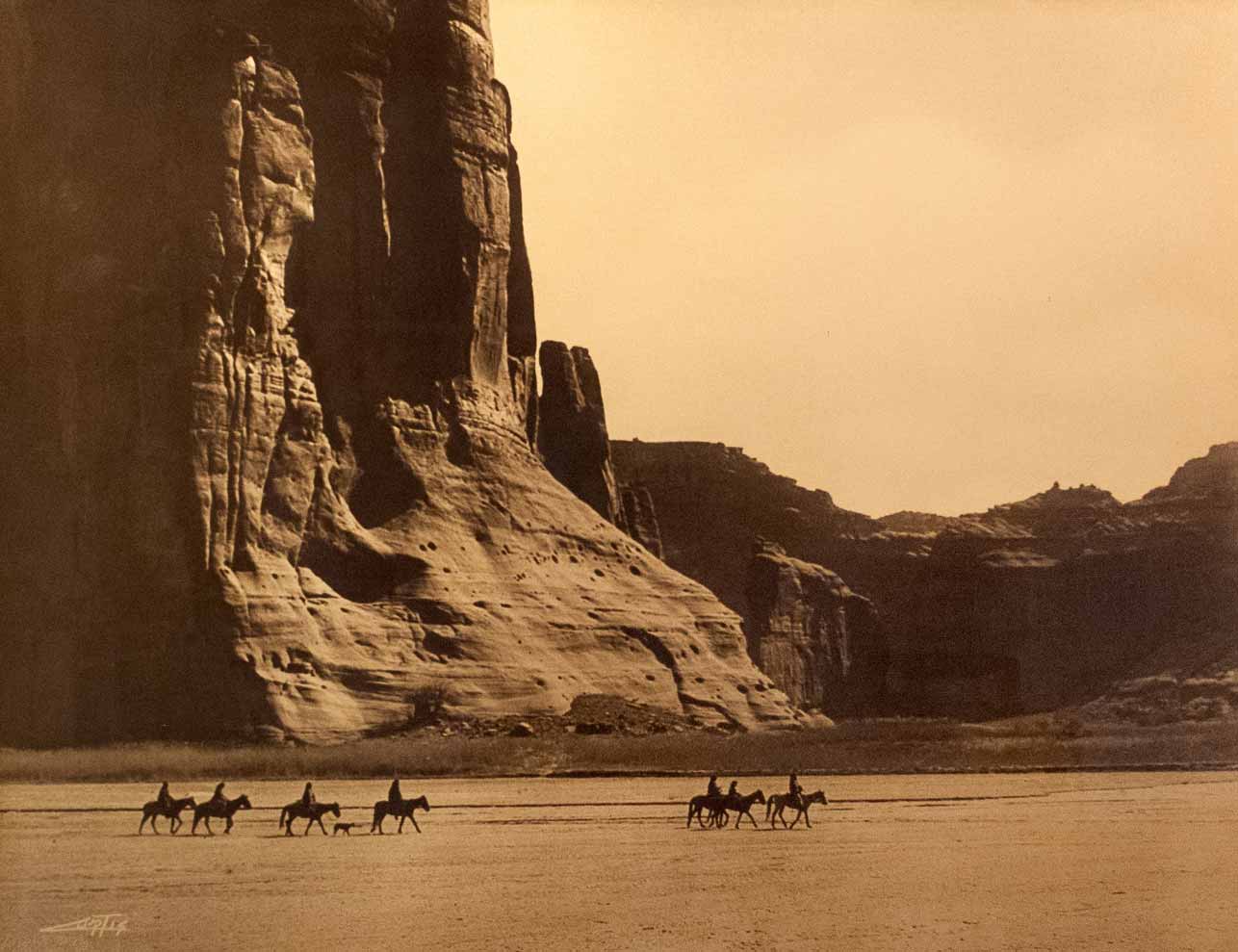

Photo Courtesy : Christopher Cardozo Fine ArtPlatinum Prints - A Zuni Girl

- Artist Edward Curtis

- Date 1903

- Dimensions 45 x 53 in

Many photography connoisseurs consider platinum prints to be the highest form of photographic expression. Platinum photographs are renowned for their exceptional richness, subtle nuance, broad tonal range, and permanence. Curtis used platinum prints for his most important exhibitions and also offered them for sale individually. Over the past decade a number of Curtis’ platinum prints have sold for over $100,000. Today they are his most prized prints and have been exhibited extensively in museums internationally. Platinum photographs are capable of yielding an exceptionally broad and delicate tonal range. The New York Public Library and the Peabody Essex Museum have important holdings of Curtis’ platinum prints.

Photo Courtesy : Christopher Cardozo Fine ArtGelatin Silver Prints – Aphrodite and Awaiting the Return of the Snake Racers

- Artist Edward Curtis

- Date Aphrodite - 1925, Awaiting the Return of the Snake Racers - 1921

- Dimensions 45 x 53 in

Curtis created traditional gelatin silver prints in a variety of forms. He created thousands of untoned “reference” prints. These 6” x 8” untoned silver prints were made in the darkroom so Curtis could see what his negatives looked like (as simple black and white prints) for reference purposes. He would then decide whether the image was good enough to justify more printing. These “reference prints” are often the only examples that survive of some of Curtis’ negatives. Curtis also created sepia-toned gelatin silver prints for exhibition and sale. He created a small body of sepia-toned silver “border” prints wherein he created a dark-toned border in the print itself through additional exposure to light in the darkroom. He also created warm-toned silver prints without a “border”. Both styles were created for sale and for exhibition. Curtis also created blue-toned silver prints for his “Hollywood” (“Aphrodite”) series of nudes and for a few other photographs.

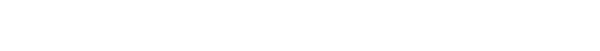

Photo Courtesy : Christopher Cardozo Fine ArtGold-Toned Printing-Out-Paper Prints - Typical Nez Perce

- Artist Edward Curtis

- Date 1899

- Dimensions 45 x 53 in

From 1898-1901 Curtis also created a very small body of gold-toned printing-out-paper prints (GTPOP). These are very scarce and prized by serious collectors for their rarity, fine grain structure, sharp resolution and their beautiful russety, sepia tones. The sharpness of their resolution is unlike Curtis’ softer photogravure and platinum prints, giving them a slightly more “documentary” feel. Unlike gelatin silver prints the GTPOP’s silver emulsion is not suspended in gelatin and development in chemicals is not required as light itself activates the image (it is what is known as a “printing-out process”). The hue of a typical GTPOP is distinct: it is sepia colored, with warm, reddish hues which distinguish them from his typical sepia colored photogravures and platinum prints. While largely forgotten today, Curtis choose GTPOP’s to exhibit as early as 1901. Only a hand-full exist today.

Photo Courtesy : Christopher Cardozo Fine ArtHand-Colored Photographs – Oasis in the Badlands

- Artist Edward Curtis

- Date 1905

- Dimensions 45 x 53 in

Curtis hand-colored photographs in at least three different mediums: platinum, silver, and photogravure. Every set of The North American Indian contain over twenty hand-colored photogravures. Curtis also created a very small body of hand-colored silver and platinum prints. For this purpose, he used both watercolors and oils.

Photo Courtesy : Christopher Cardozo Fine ArtCyanotype - Red Plume - Piegan

- Artist Edward Curtis

- Date 1905

- Dimensions 45 x 53 in

Cyanotype is a photographic printing process that produces a cyan-blue print. It is a simple, low-cost process for printing. Curtis used it extensively in the field because it was inexpensive and did not require enlarging equipment or developing chemicals. It is presumed that nearly all of Curtis’ nearly 40,000 negatives were initially printed, in the field, as cyanotypes, very few of which have survived.

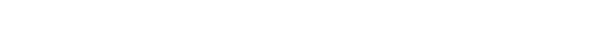

Photo Courtesy : Christopher Cardozo Fine ArtThe Complete Reference Edition

- Artist Edward Curtis, Reproduced by Christopher Cardozo

- Dimensions 45 x 53 in

“Hundreds of Curtis’s vintage photographs have never been reproduced and, therefore, remain largely unknown,” Cardozo said. “This is even more true for the more than two million words of superb ethnographic text and transcriptions of language and music. Thus, while Curtis may be the most widely exhibited and collected photographer in the history of the medium, a great deal of his oeuvre remains largely unknown.” This is part of the reason why Cardozo, a photographer and historian himself, has undertaken the monumental task of recreating The North American Indian, a twenty-volume, twenty-portfolio set of books. Cardozo tripled his staff and invested over $1,000,000 for this republication. The “Custom Limited Edition” version involved thousands of hours of hand work and complete sets now reside at The Morgan Library and at Harvard University. Cardozo has recently released a more affordably priced “Complete Reference Edition”, which is identical in content to the Custom Limited Edition. The “Complete Reference Edition” is beautifully and durably produced but was not hand assembled and bound. Cardozo hopes that in doing so, not only will Curtis’ remarkable scholarship will be more accessible to the public, but collectors and art enthusiasts will become more familiar with Curtis’ skill and dedication to his craft.

Photo Courtesy : Christopher Cardozo Fine ArtPhotogravure - An Oasis in the Badlands - Sioux

Photogravure is an expensive and time-consuming method of producing fine photographic prints. It was known as the “king of printing processes” because of its ability to consistently produce rich, finely detailed prints, which made it ideal for Curtis’ forty volume magnum opus The North American Indian. Approximately 98% of all surviving Curtis prints are photogravures because Curtis chose photogravure for the prints needed for his sets of books. Each set was illustrated by over 2,000 images, all printed in the photogravure process.

Photo Courtsey of Christopher Cardozo Fine ArtGoldtone - Canyon de Chelly

Curtis pioneered and popularized the goldtone process (also known as “Curt-tone” or “oro-tone”). Goldtones are printed directly on glass and backed with a gold liquid wash. This gives them extraordinary luminosity and three-dimensionality. It was Curtis’ favorite process and he is acknowledged as the foremost creator of goldtones. Goldtones comprise less than 1% of Curtis’ surviving photographs and are prized by many collectors. Each goldtone was sold with an Arts and Crafts influenced hand-made frame.

Photo Courtsey of Christopher Cardozo Fine ArtPlatinum Prints - A Zuni Girl

Many photography connoisseurs consider platinum prints to be the highest form of photographic expression. Platinum photographs are renowned for their exceptional richness, subtle nuance, broad tonal range, and permanence. Curtis used platinum prints for his most important exhibitions and also offered them for sale individually. Over the past decade a number of Curtis’ platinum prints have sold for over $100,000. Today they are his most prized prints and have been exhibited extensively in museums internationally. Platinum photographs are capable of yielding an exceptionally broad and delicate tonal range. The New York Public Library and the Peabody Essex Museum have important holdings of Curtis’ platinum prints.

Photo Courtsey of Christopher Cardozo Fine ArtGelatin Silver Prints – Aphrodite and Awaiting the Return of the Snake Racers

- Artist Edward Curtis

- Date Aphrodite - 1925, Awaiting the Return of the Snake Racers - 1921

- Dimensions 45 x 53 in

Curtis created traditional gelatin silver prints in a variety of forms. He created thousands of untoned “reference” prints. These 6” x 8” untoned silver prints were made in the darkroom so Curtis could see what his negatives looked like (as simple black and white prints) for reference purposes. He would then decide whether the image was good enough to justify more printing. These “reference prints” are often the only examples that survive of some of Curtis’ negatives. Curtis also created sepia-toned gelatin silver prints for exhibition and sale. He created a small body of sepia-toned silver “border” prints wherein he created a dark-toned border in the print itself through additional exposure to light in the darkroom. He also created warm-toned silver prints without a “border”. Both styles were created for sale and for exhibition. Curtis also created blue-toned silver prints for his “Hollywood” (“Aphrodite”) series of nudes and for a few other photographs.

Photo Courtsey of Christopher Cardozo Fine ArtGold-Toned Printing-Out-Paper Prints - Typical Nez Perce

From 1898-1901 Curtis also created a very small body of gold-toned printing-out-paper prints (GTPOP). These are very scarce and prized by serious collectors for their rarity, fine grain structure, sharp resolution and their beautiful russety, sepia tones. The sharpness of their resolution is unlike Curtis’ softer photogravure and platinum prints, giving them a slightly more “documentary” feel. Unlike gelatin silver prints the GTPOP’s silver emulsion is not suspended in gelatin and development in chemicals is not required as light itself activates the image (it is what is known as a “printing-out process”). The hue of a typical GTPOP is distinct: it is sepia colored, with warm, reddish hues which distinguish them from his typical sepia colored photogravures and platinum prints. While largely forgotten today, Curtis choose GTPOP’s to exhibit as early as 1901. Only a hand-full exist today.

Photo Courtsey of Christopher Cardozo Fine ArtHand-Colored Photographs – Oasis in the Badlands

Curtis hand-colored photographs in at least three different mediums: platinum, silver, and photogravure. Every set of The North American Indian contain over twenty hand-colored photogravures. Curtis also created a very small body of hand-colored silver and platinum prints. For this purpose, he used both watercolors and oils.

Photo Courtsey of Christopher Cardozo Fine ArtCyanotype - Red Plume - Piegan

Cyanotype is a photographic printing process that produces a cyan-blue print. It is a simple, low-cost process for printing. Curtis used it extensively in the field because it was inexpensive and did not require enlarging equipment or developing chemicals. It is presumed that nearly all of Curtis’ nearly 40,000 negatives were initially printed, in the field, as cyanotypes, very few of which have survived.

Photo Courtsey of Christopher Cardozo Fine ArtThe Complete Reference Edition

“Hundreds of Curtis’s vintage photographs have never been reproduced and, therefore, remain largely unknown,” Cardozo said. “This is even more true for the more than two million words of superb ethnographic text and transcriptions of language and music. Thus, while Curtis may be the most widely exhibited and collected photographer in the history of the medium, a great deal of his oeuvre remains largely unknown.” This is part of the reason why Cardozo, a photographer and historian himself, has undertaken the monumental task of recreating The North American Indian, a twenty-volume, twenty-portfolio set of books. Cardozo tripled his staff and invested over $1,000,000 for this republication. The “Custom Limited Edition” version involved thousands of hours of hand work and complete sets now reside at The Morgan Library and at Harvard University. Cardozo has recently released a more affordably priced “Complete Reference Edition”, which is identical in content to the Custom Limited Edition. The “Complete Reference Edition” is beautifully and durably produced but was not hand assembled and bound. Cardozo hopes that in doing so, not only will Curtis’ remarkable scholarship will be more accessible to the public, but collectors and art enthusiasts will become more familiar with Curtis’ skill and dedication to his craft.

Photo Courtsey of Christopher Cardozo Fine Art