Despite an abundance of controversial topics to comment on, America’s editorial cartoonists have had a rough time lately. In January 2019, the Gannett-owned Arizona Republic newspaper axed Steve Benson, the Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist whose sharp sketches had livened up its pages for almost forty years.

As Michael Cavna wrote in the Washington Post, Benson joined a cadre of high-profile staff cartoonists laid off in recent years, as the newspapers that employed them have faced declining revenues and rising pressure from owners who care more about profit than content. Other recent casualties include Rob Rogers of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Charlie Daniel at the Knoxville News-Sentinel, and Nick Anderson of the Houston Chronicle. “This is a worrisome trend,” Benson told Cavna. “Cartoonists are canaries in the coal mine—and we draw darned good canaries. This is a foreshadowing of more to come.”

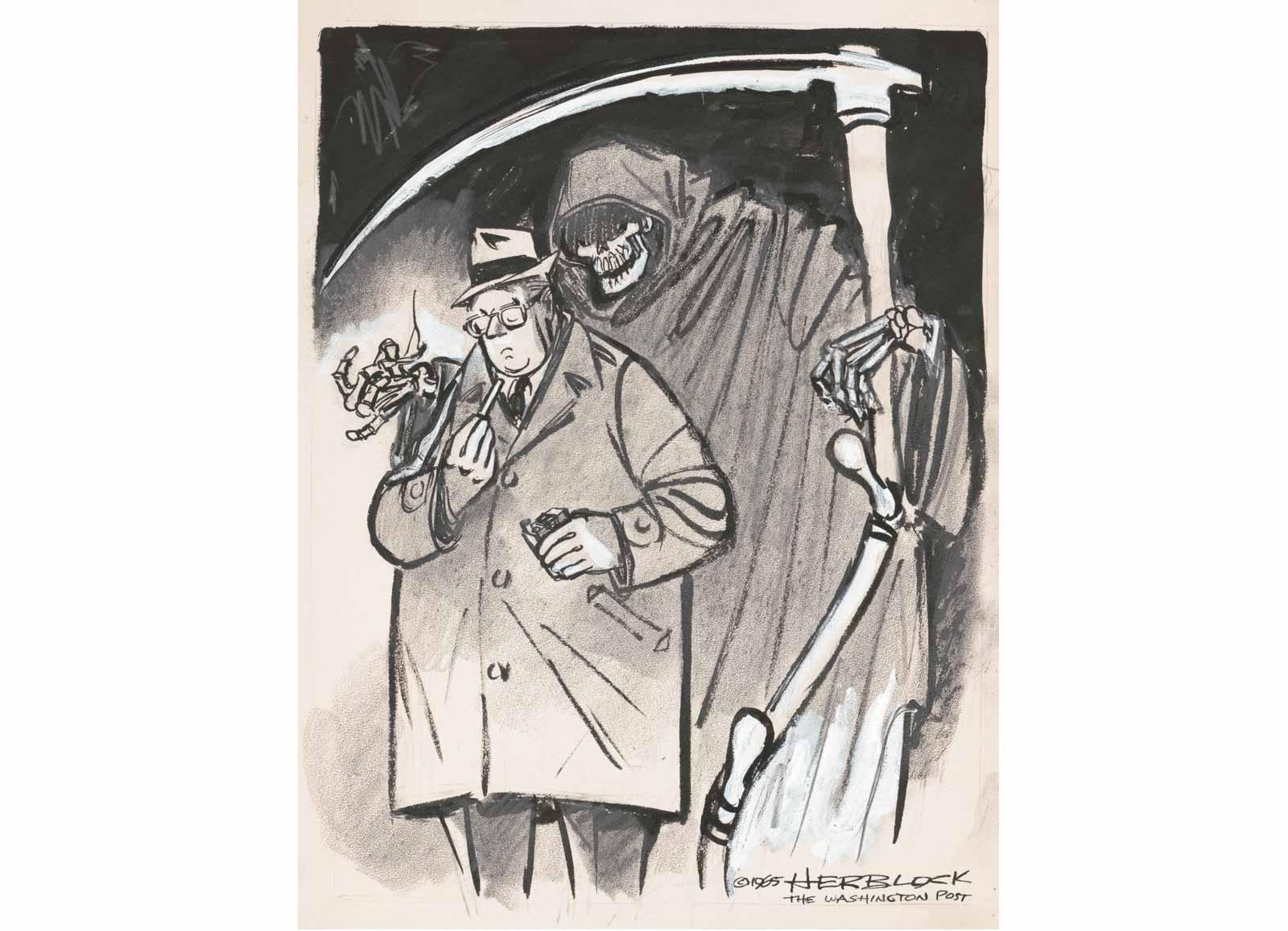

Even as traditional outlets for it shrink, socially conscious art and the desire to make it remain as strong as ever. Art in Action, a 2019 exhibition at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., makes the point that editorial cartooning, in some form, has been with us a long time. And it continues to persist even as traditional outlets for it shrink.

The problem has never been a shortage of material. The Trump era has given artists an excess of subjects to sharpen their pens on. And while the digital era has disrupted some channels artists once used to distribute their work—newspapers, for instance—it has also made it possible to make and distribute art more widely. Artists now share their output via grassroots networks and social media instead of via print media.

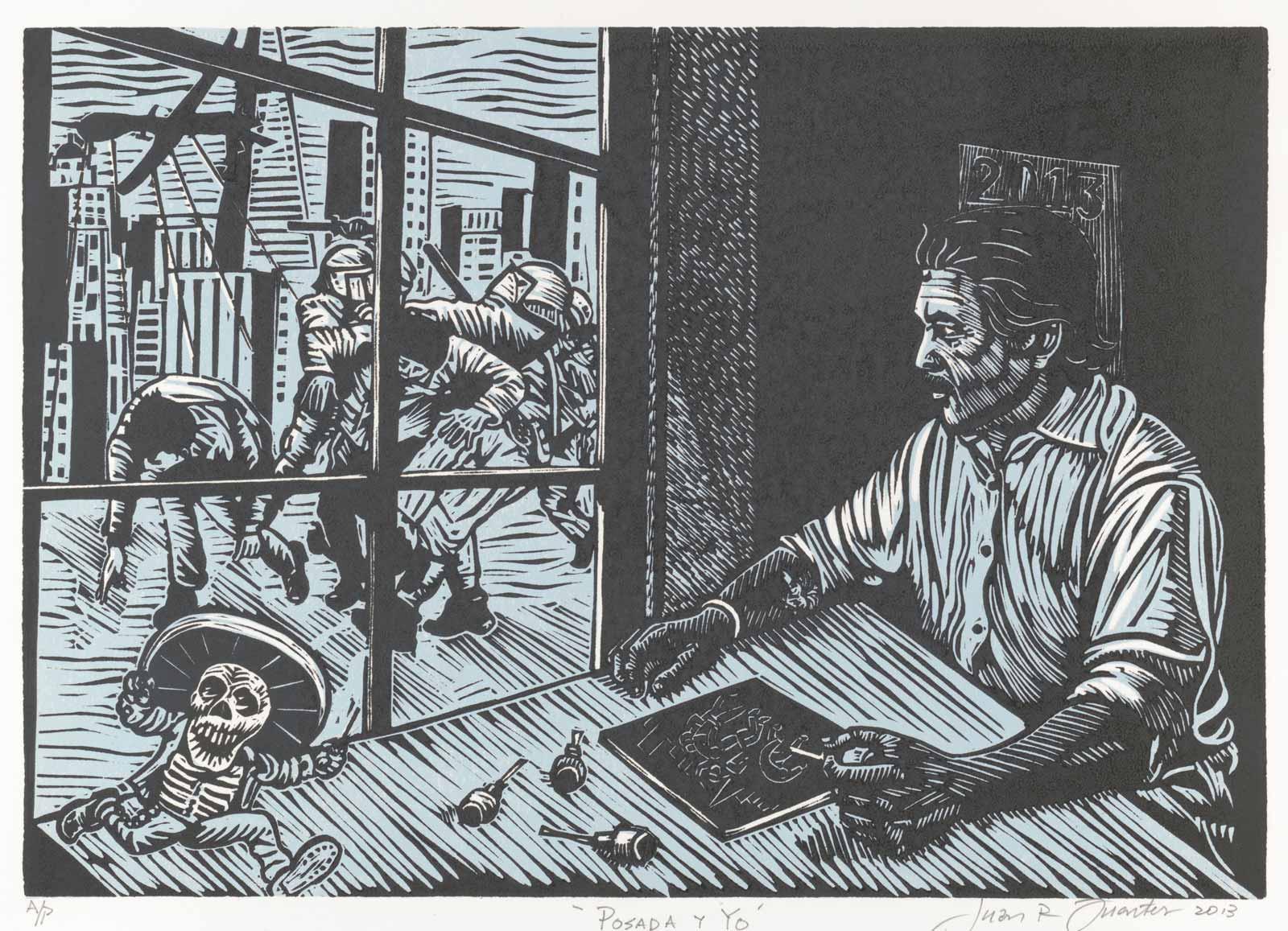

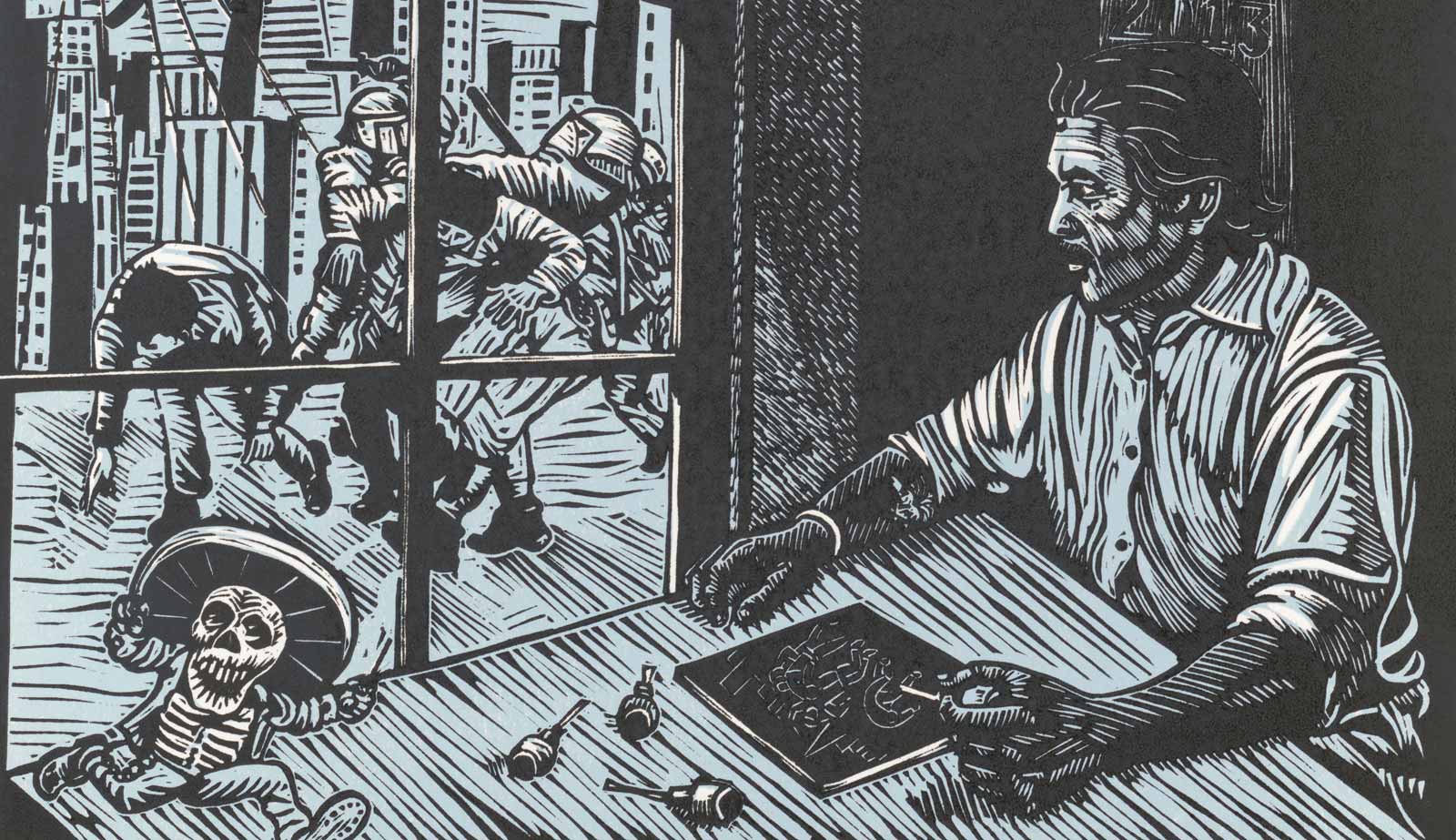

![cartoon-slides-02.jpg Leopoldo Méndez (1902–1969). Posada en su taller [Posada in His Workshop], 1953. Linocut.](https://cdn.artandobject.com/sites/default/files/styles/media_crop/public/cartoon-slides-02.jpg?itok=aMGRsF3O)