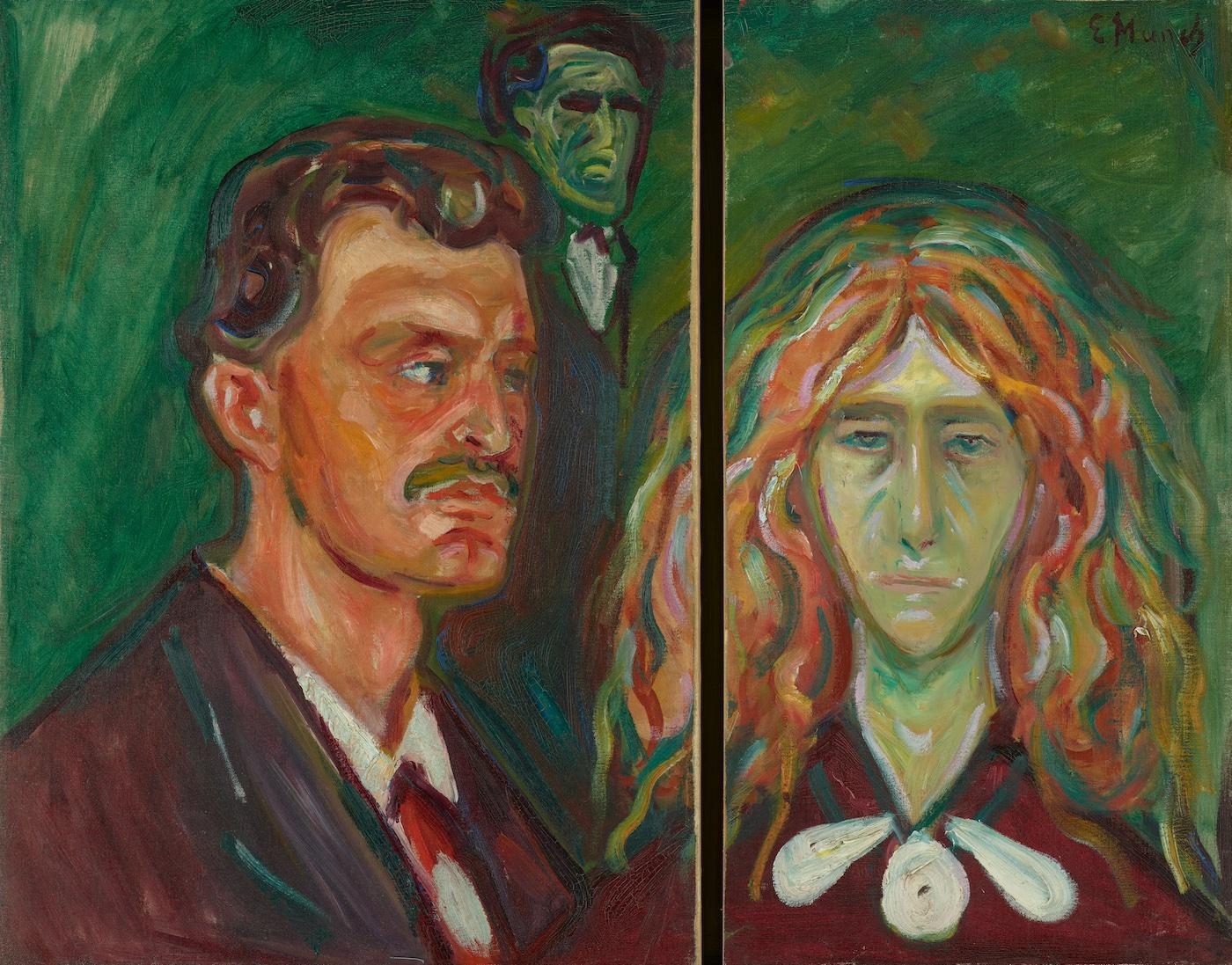

Born in 1863 in Loten, Norway, Munch didn’t have an easy life. His childhood was marked by the tragic death of his mother and sister, and he constantly suffered from poor health and later, alcoholism and mental disorders, due to other traumas and personal issues.

His artistic talent manifested while he was still a child, and despite his troubled life, he visited and lived in many European cities where he was influenced, inspired by, and developed various artistic techniques and styles.

Among others, Paris, Kristiania (today Oslo), and Berlin were especially important milestones in Munch’s intellectual and artistic formation. The artistic and literary group of The Kristiania Bohème, which included the anarchic writer Hans Jæger and the painter Christian Krohg, influenced him dramatically. They were supporters of free sexuality, critics of religion, gender, and class prejudices, and their members’ thoughts contributed to shaping many of Munch’s progressive and modern ideas.