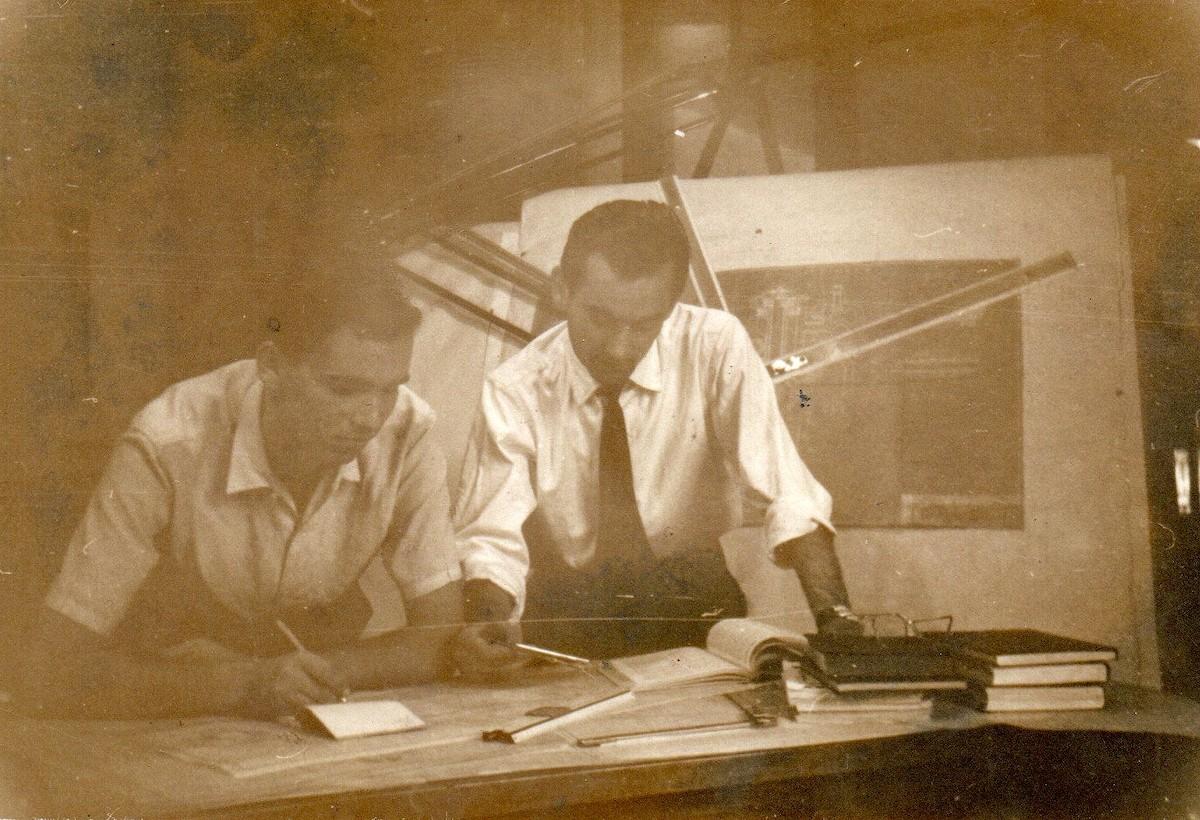

The Almaviva Archive began on paper notebooks in the 1960s when Almaviva’s wife, Maria Luisa, got into the habit of keeping a written record of all his paintings, which ones were sold and to whom, and the exhibitions in which he took part. Other materials included in the archive are past correspondence, exhibition catalogs, and art and history books. A considerable part of these sources are useful for keeping track of the artist's past and ongoing work.

Almaviva also recognizes how his archive helped him remember details of a career that spans five decades. “To discover a painting that I had forgotten was surprising and sometimes left me feeling slightly disoriented," he said. "Such discoveries allowed me to engage with the complex and unpredictable universe of collectors, admirers, and supporters.”

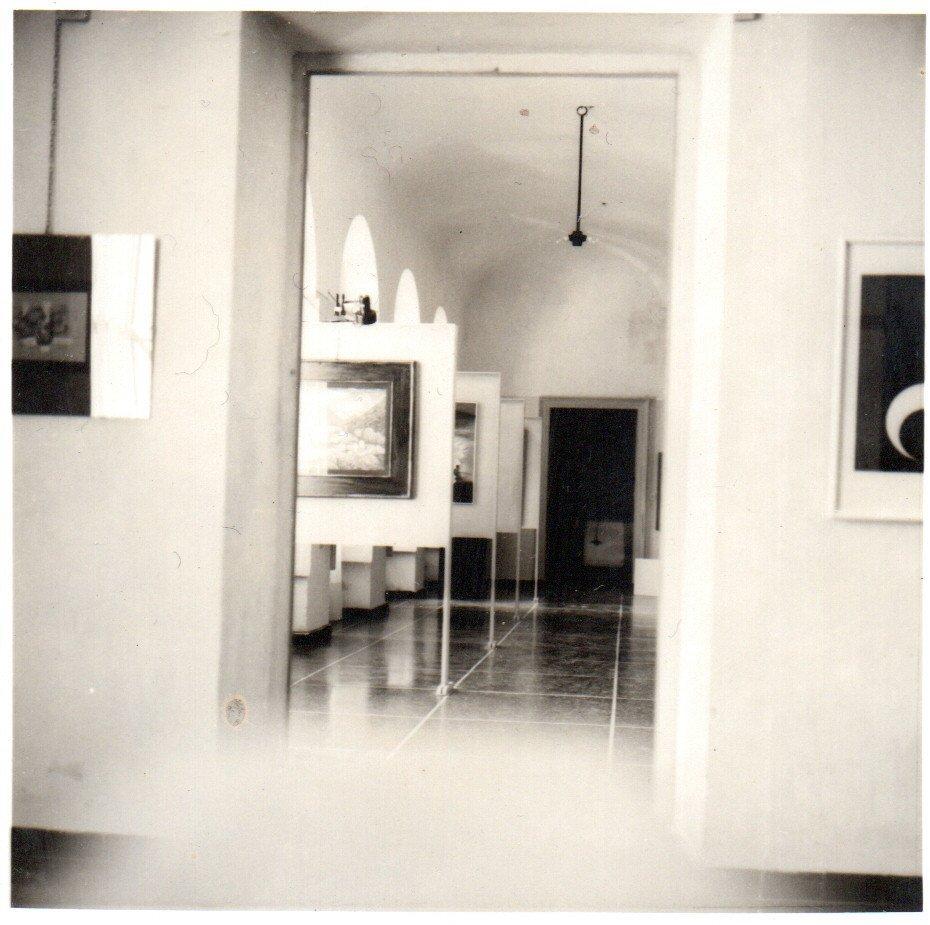

The archive is not just about remembrance but also about self-assurance, a way to protect for posterity an artist’s viewpoint and innovative accomplishments in a field. This was especially crucial for Almaviva as he pushed the boundaries of painting through the new styles of Tonaltimbrica and Filoplastica. Backed by an archive that offered a solid background of the art environment of the second half of the 20th century, he was able to claim the originality of his works and his pursuit of innovation.