To create his photograph, Niépce treated a heated pewter plate with bitumen of Judea, or Syrian asphalt, a naturally occurring asphalt with light-sensitive properties. The plate was placed in a camera obscura facing out his second-story window. Niépce kept the camera open for at least eight hours, and possibly as long as two days. The bitumen hardened where the light was strongest, creating an image of the streetscape that only became visible once the unhardened parts of asphalt were removed.

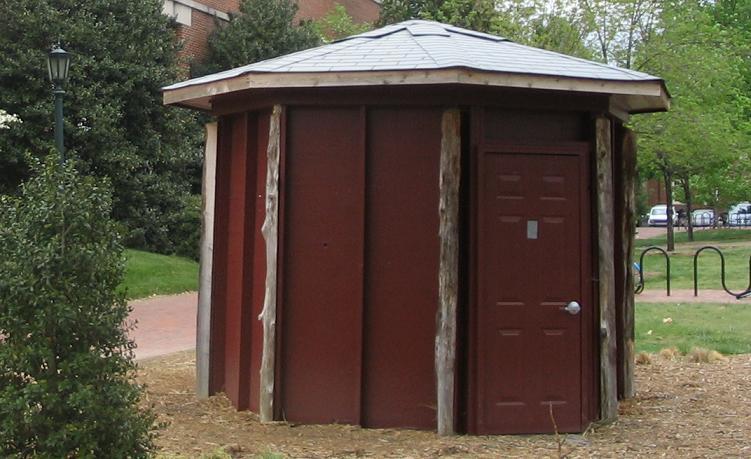

Portable Camera Obscura, 1800s. Goethe Nationalmuseum, Weimar, Germany.

Taken in 1826 or 1827 by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, the world’s oldest surviving photograph was captured using a technique Niépce invented called heliography, which produces one-of-a-kind images on metal plates treated with light-sensitive chemicals.

Not particularly impressive at first glance, Niépcein’s View from the Window at Le Gras is a grey-hued pewter plate with the blurred shadow-shapes of treelines and buildings―a digitally retouched copy makes the images easier to discern. Despite its unprepossessing appearance, this photograph was integral to the development of modern photography.

Also known as a pinhole camera, the camera obscura has been used for centuries to watch eclipses without damaging vision, as a drawing aid, and for scientific experiments. While the term photography wasn’t coined until the nineteenth century, humanity has had a long fascination with photographic effects. Historians suspect Neolithic peoples used the camera obscura effect in some of their monuments. The Ancient Chinese philosopher Mozi (470 to 390 BCE) made the earliest known written reference to the camera obscura, while Renaissance artists used the devices as drawing tools. The first clear description of a camera obscura device resides in a sketchbook of Leonardo da Vinci’s from 1502. Da Vinci went on to sketch approximately 270 diagrams of the devices over the years.

A camera obscura works similarly to the human eye. Latin for “dark chamber,” the earliest versions were darkened rooms with a small hole, like the pupil of an eye, admitting light. An inverted image of the outside scene was projected through the hole onto the whitened opposite wall. Over time, camera obscuras grew smaller and more portable, becoming the ancestors of the modern camera. Angled mirrors were added to many in order to orient the reflected image right side up.

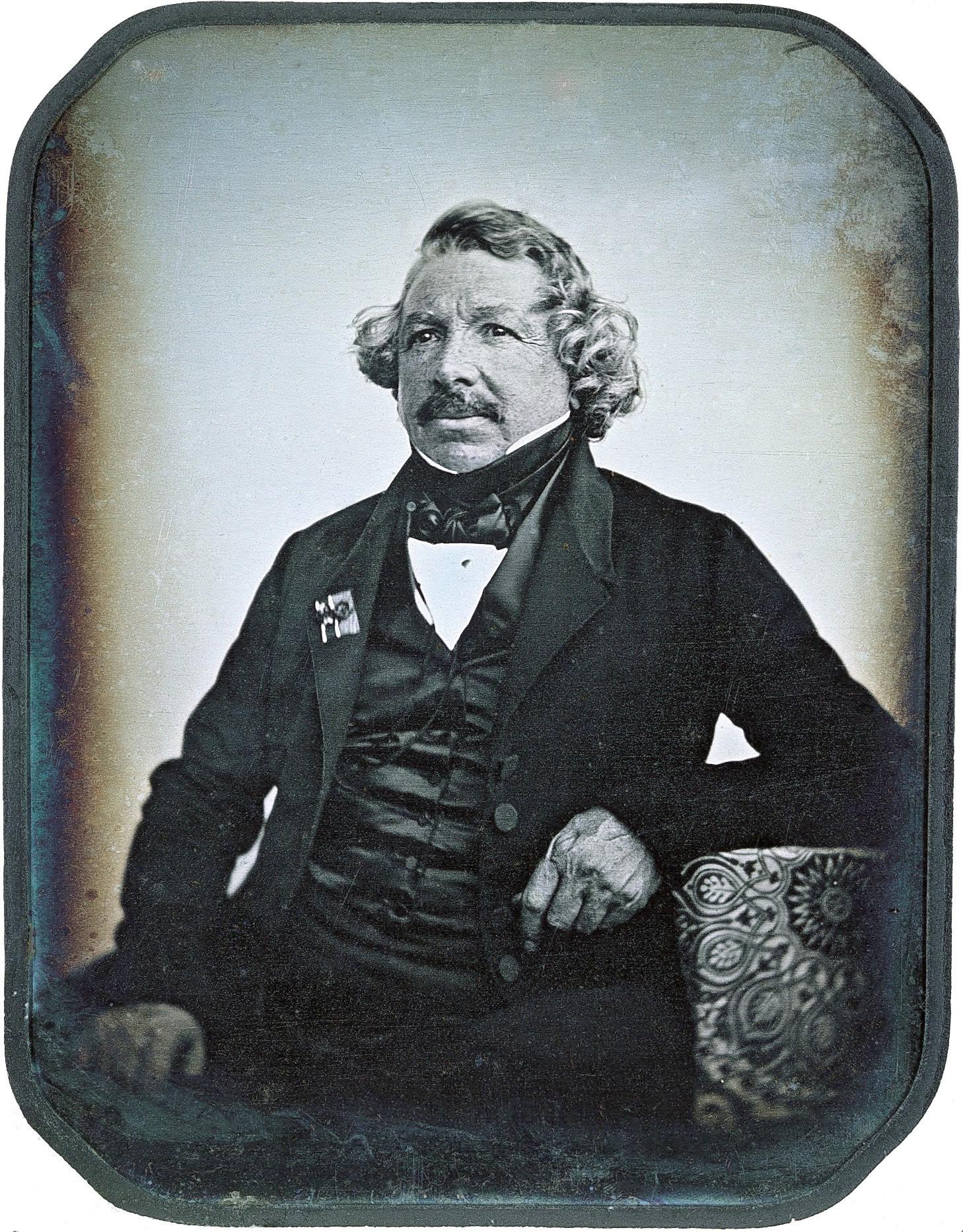

Jean-Baptiste Sabatier-Blot, Portrait of Louis Daguerre, 1844. Daguerreotype. George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY.

In 1829, Niépce joined forces with Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, another pioneer in photography. After Niépce’s sudden death in 1833, his son Isidore continued working with Daguerre. Together, they devised a system—which involved a silver-iodide plate exposed to mercury fumes—to produce high-quality images within minutes. The process became known as ‘the daguerreotype’ and the images produced as daguerreotypes.

Unknown (American), Seated Young Man Resting Arm on Table Beside Daguerreotype Case, 1840s. Daguerreotype with applied color. Image dimensions: 2 11/16 x 2 3/16 in (6.9 x 5.5 cm).

In 1839, in exchange for lifetime pensions, the French government bought their photography technique and it became the first publicly available photo-taking system. This availability played a huge role in the development of photography as a social phenomenon.

While nineteenth-century photography took considerably more time than the seconds it takes to shoot and post a selfie on social media, we owe a lot to the inventions of Niépce and Daguerre.