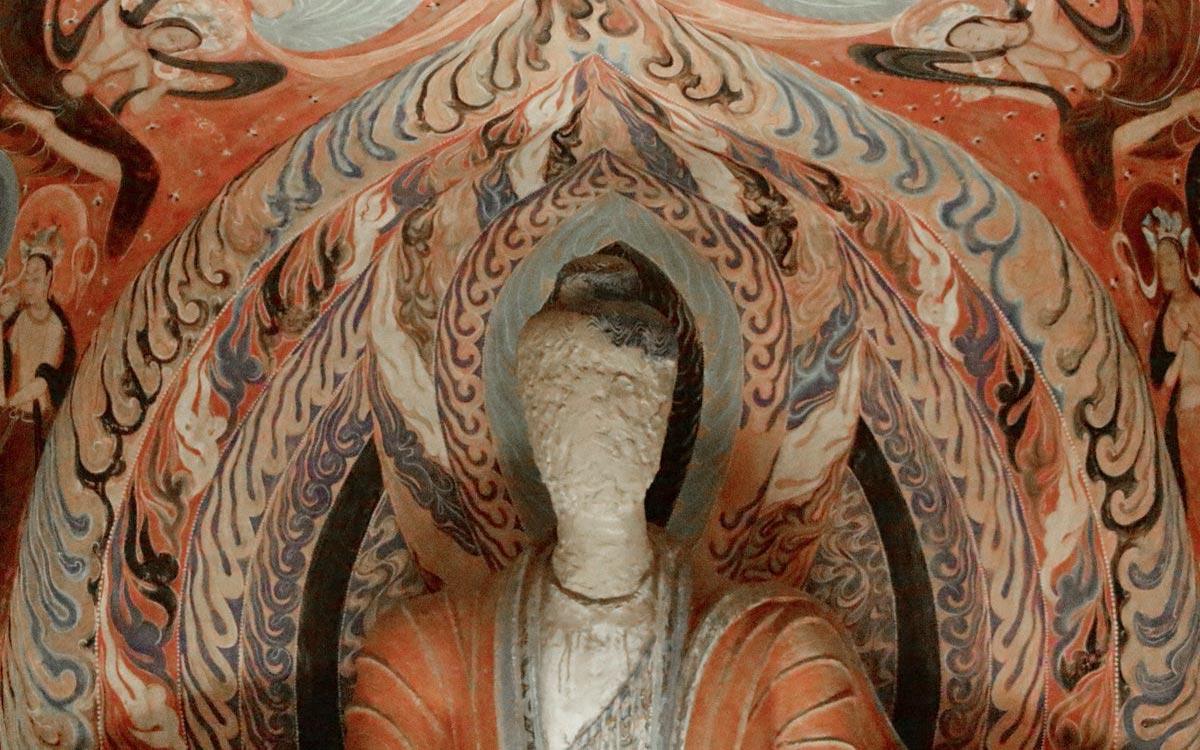

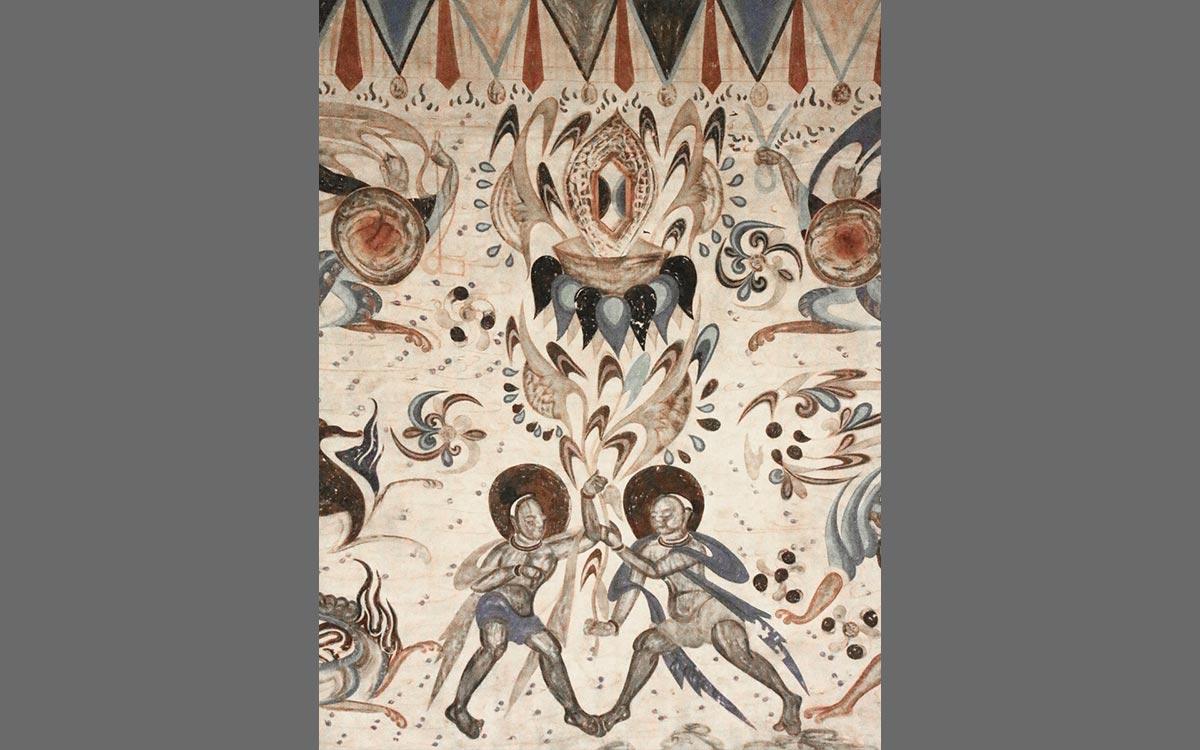

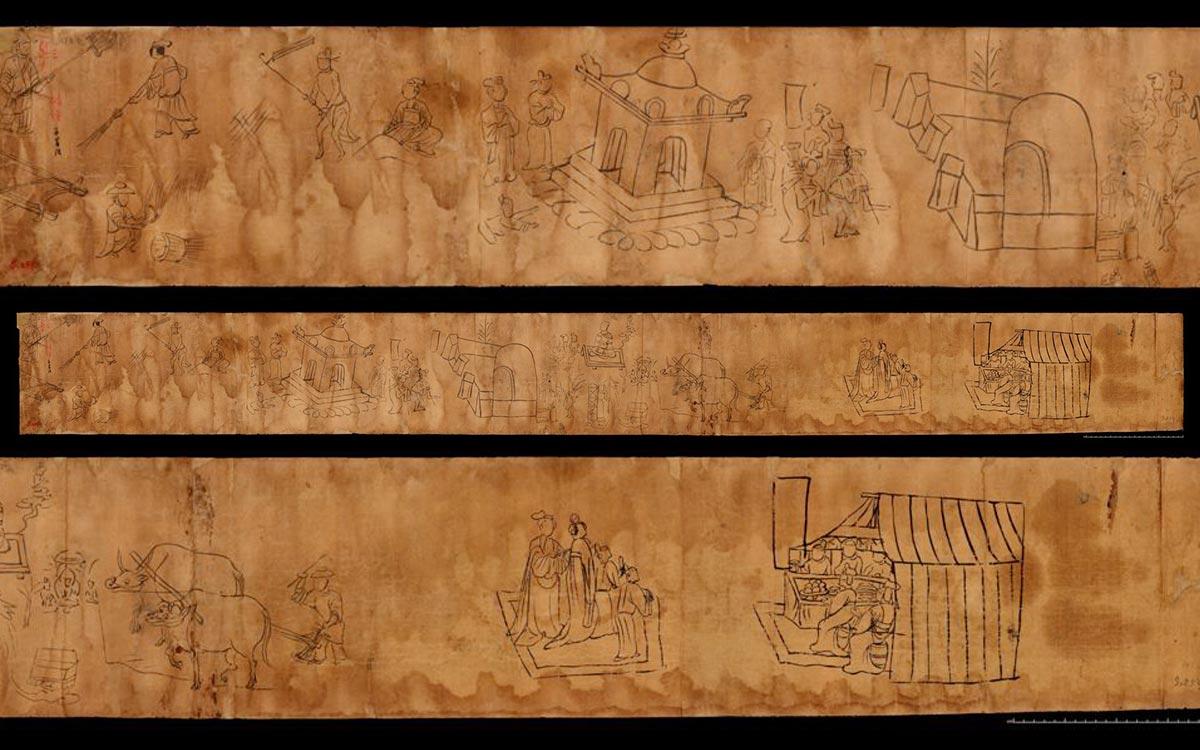

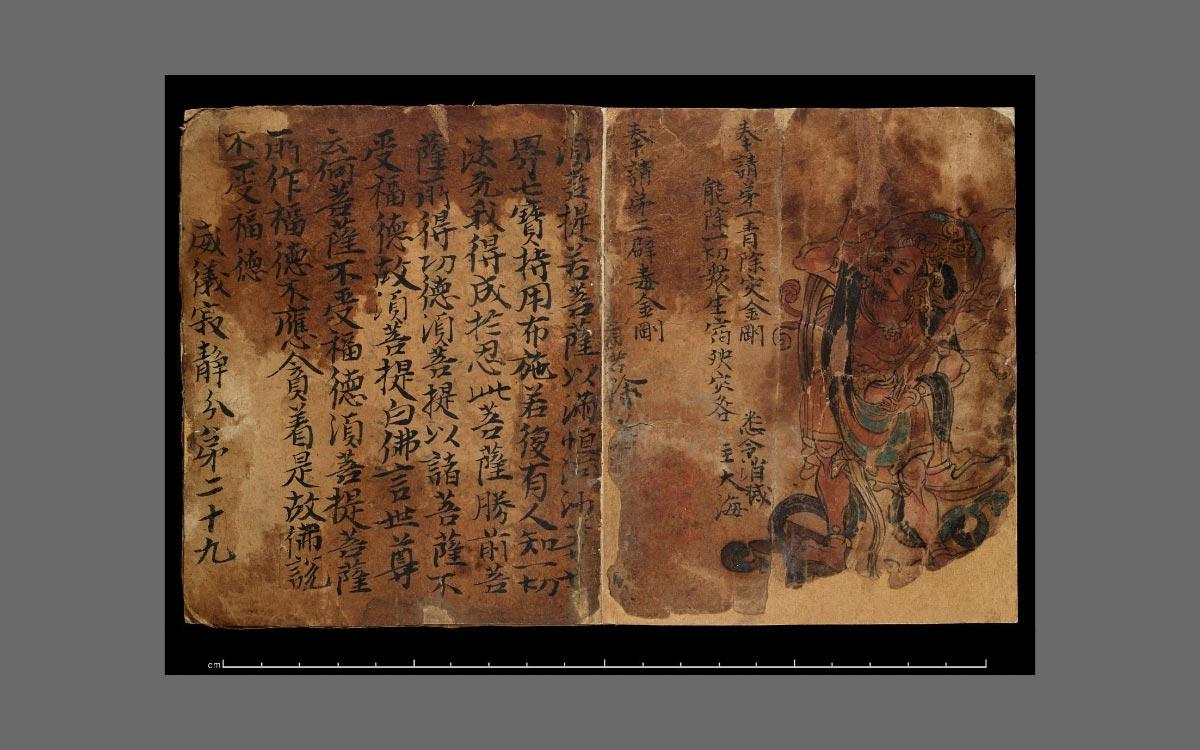

In the remote western landscape of China, on the edge of the Gobi Desert, sits Dunhuang, a lonely city of about 200,000 that was once one of the region's most vital hubs. Established as a garrison outpost in 111 BCE, from 400 AD it grew into a thriving crossroads of art, culture, trade, and ideas stemming from a wide range of influences from the Middle East, Persia, China, India, Greece, and Rome. Evidence of its illustrious past can be found in the nearby UNESCO certified Mogao Caves, a lonely stone cliff pocked with over 700 man-made recesses. Around 500 of these have painted interiors equivalent to a wall of art 15 feet high and six miles long.

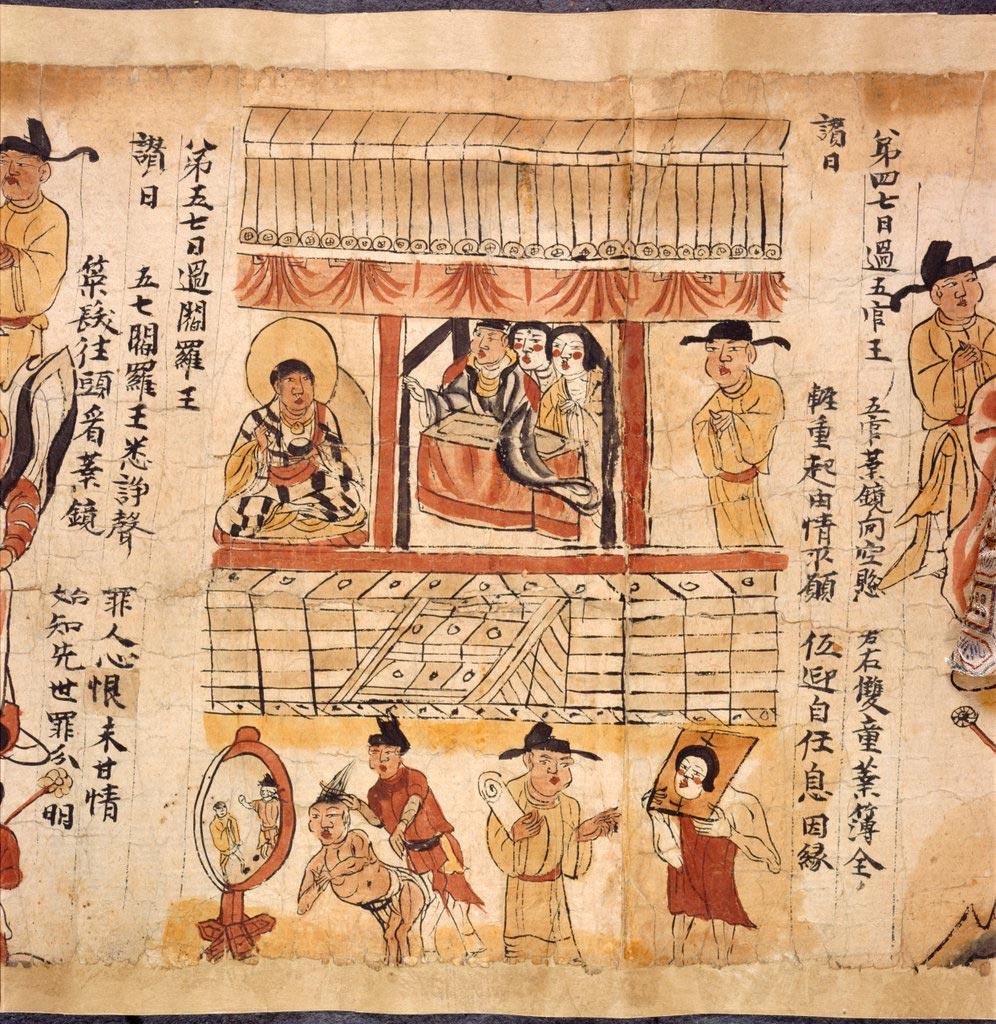

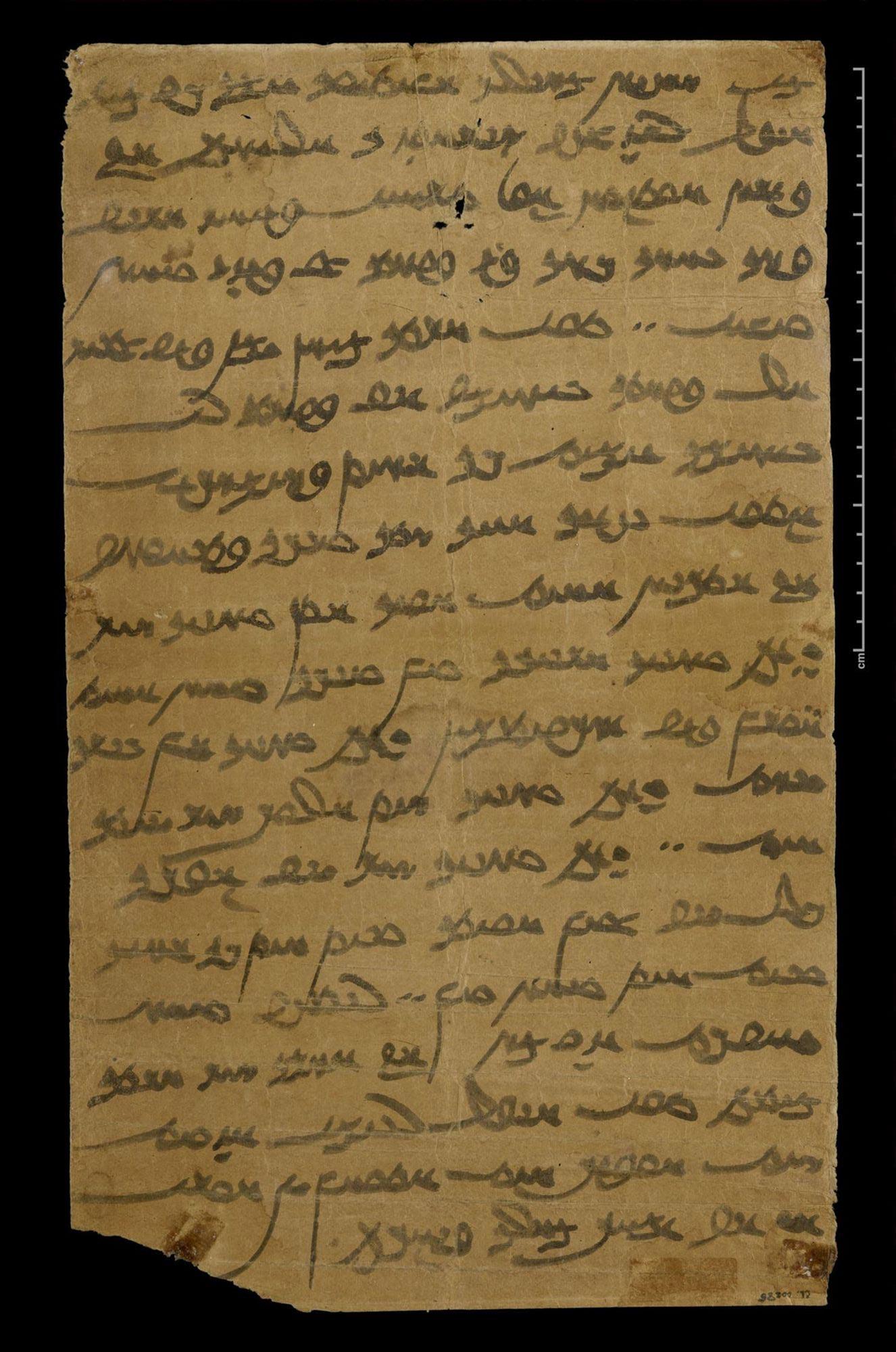

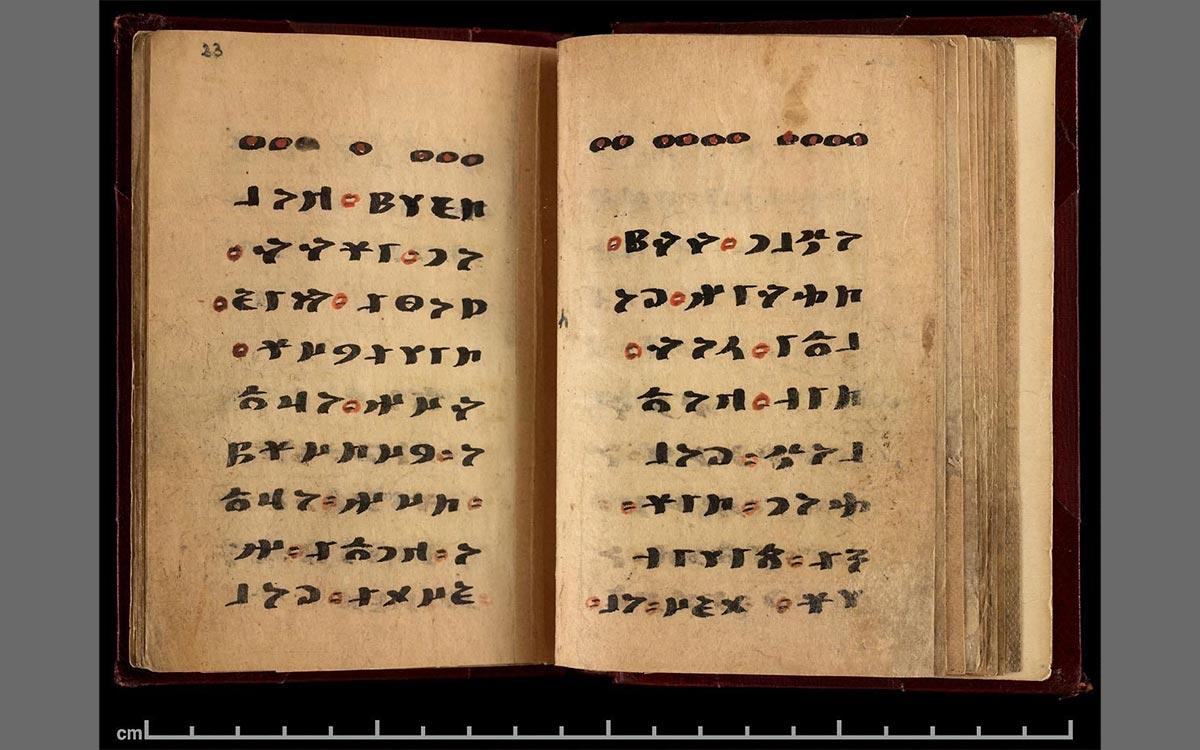

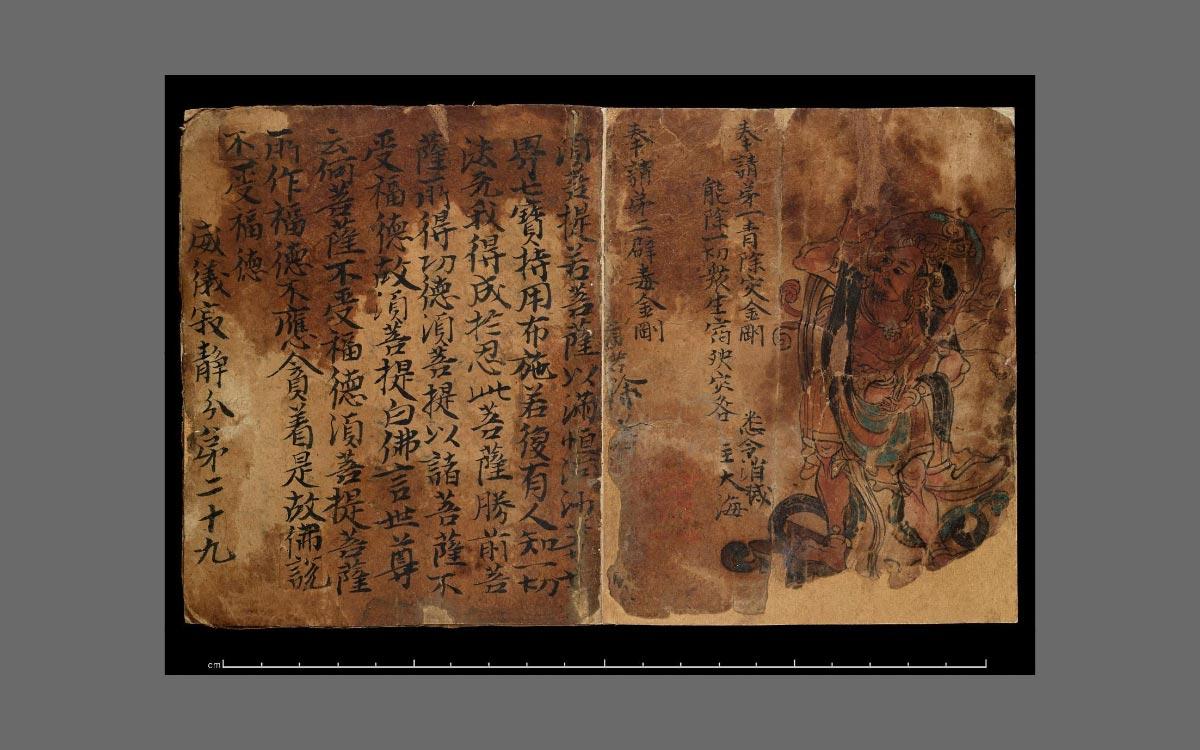

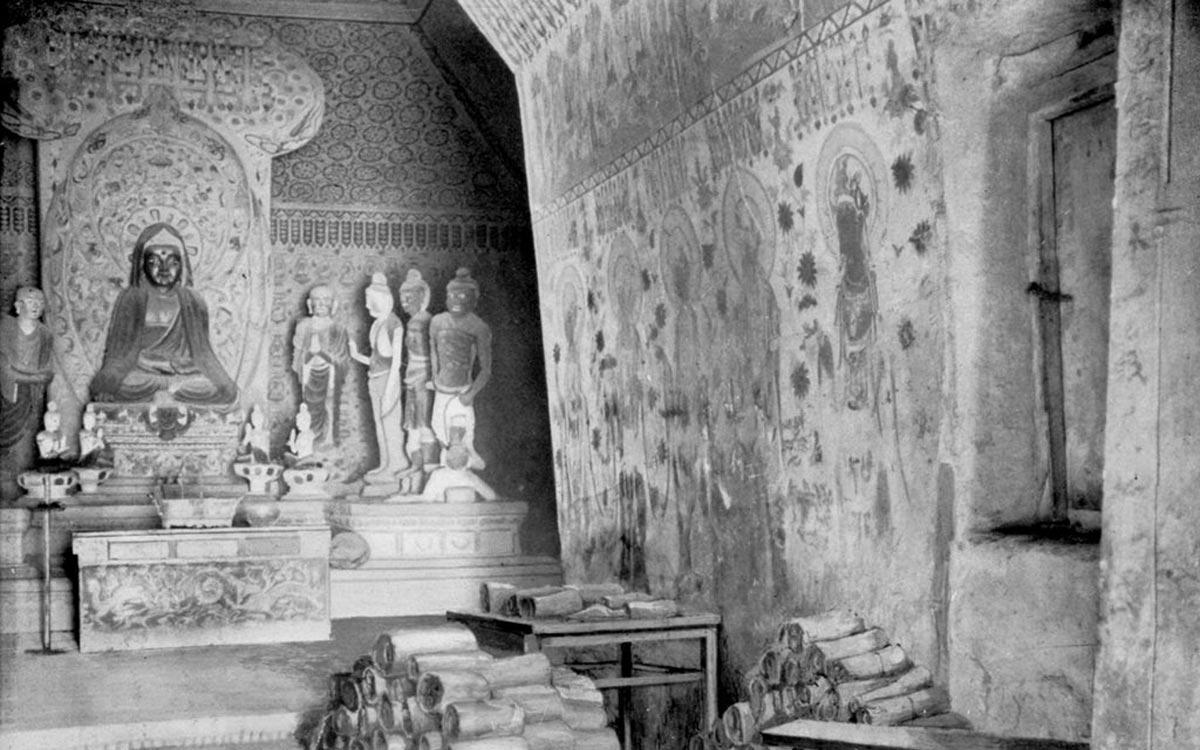

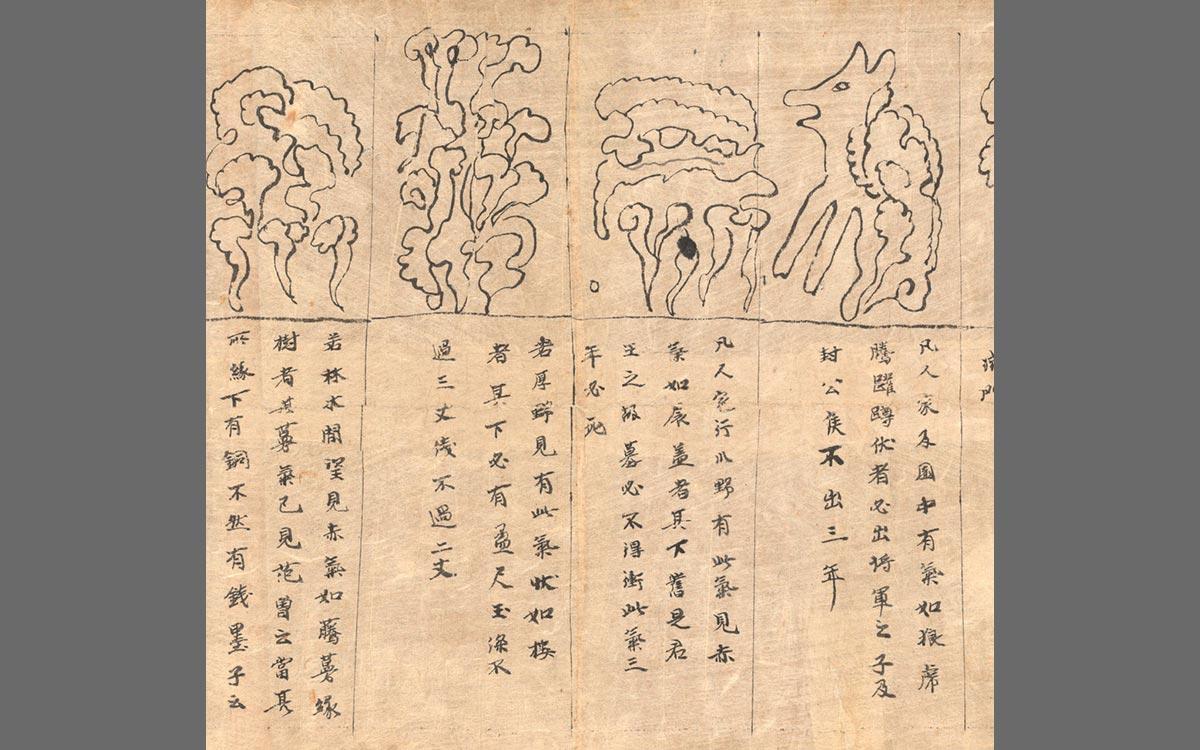

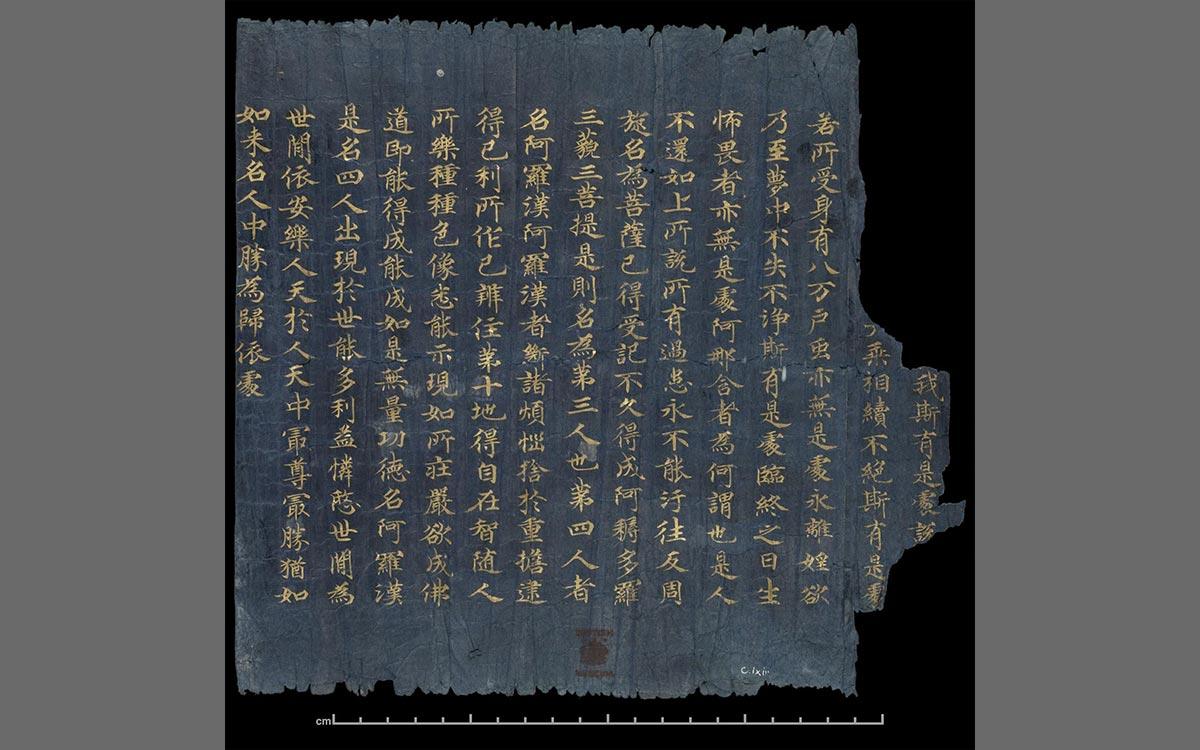

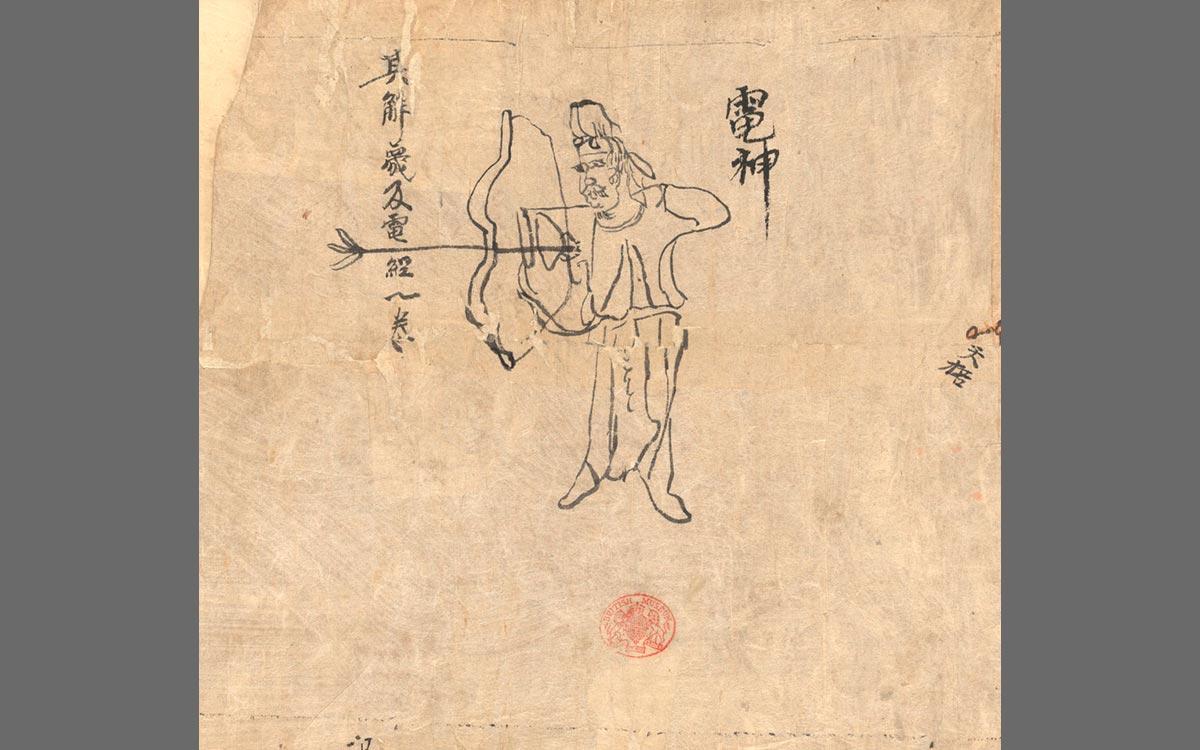

At the end of the 19th century, a Taoist priest called Abbot Wang Yuanlu, who appointed himself caretaker, discovered a chamber that became known as the Library Cave, sealed since the 11th century. In it were 40,000 objects– documents, scrolls, business contracts, drawings, and ephemera, as well as priceless works of art. In 1908, a 30-year-old French monk by the name of Paul Pelliot, a polyglot speaking 25 languages and already a tenured professor at the French University of Hanoi, pored through 10,000 documents in just three weeks, unlocking the mysteries of the caves.