In retrospect, these declarations often run parallel with the politics of a particular place and time. They are also usually a revolt against some earlier manifestation made by a different, if tangentially related, group of artists. Such is the case of the Neo-Concrete Movement.

The Brazilian poet, essayist, and art critic Ferreira Gullar is credited with writing the original Neo-Concrete Manifesto. It was also Gullar who first identified a need to react against the rigidity and cool rationalism of geometric abstraction that arose in Europe after WWI.

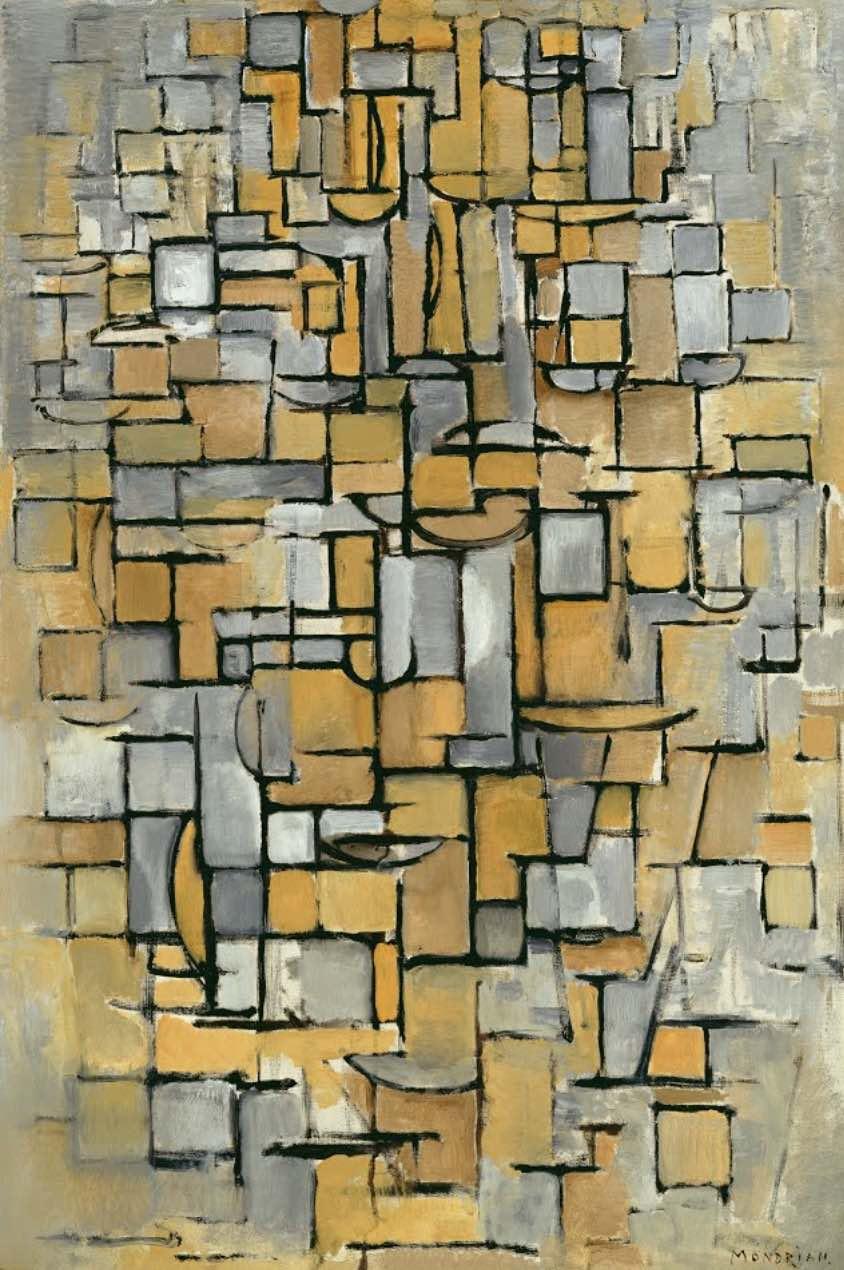

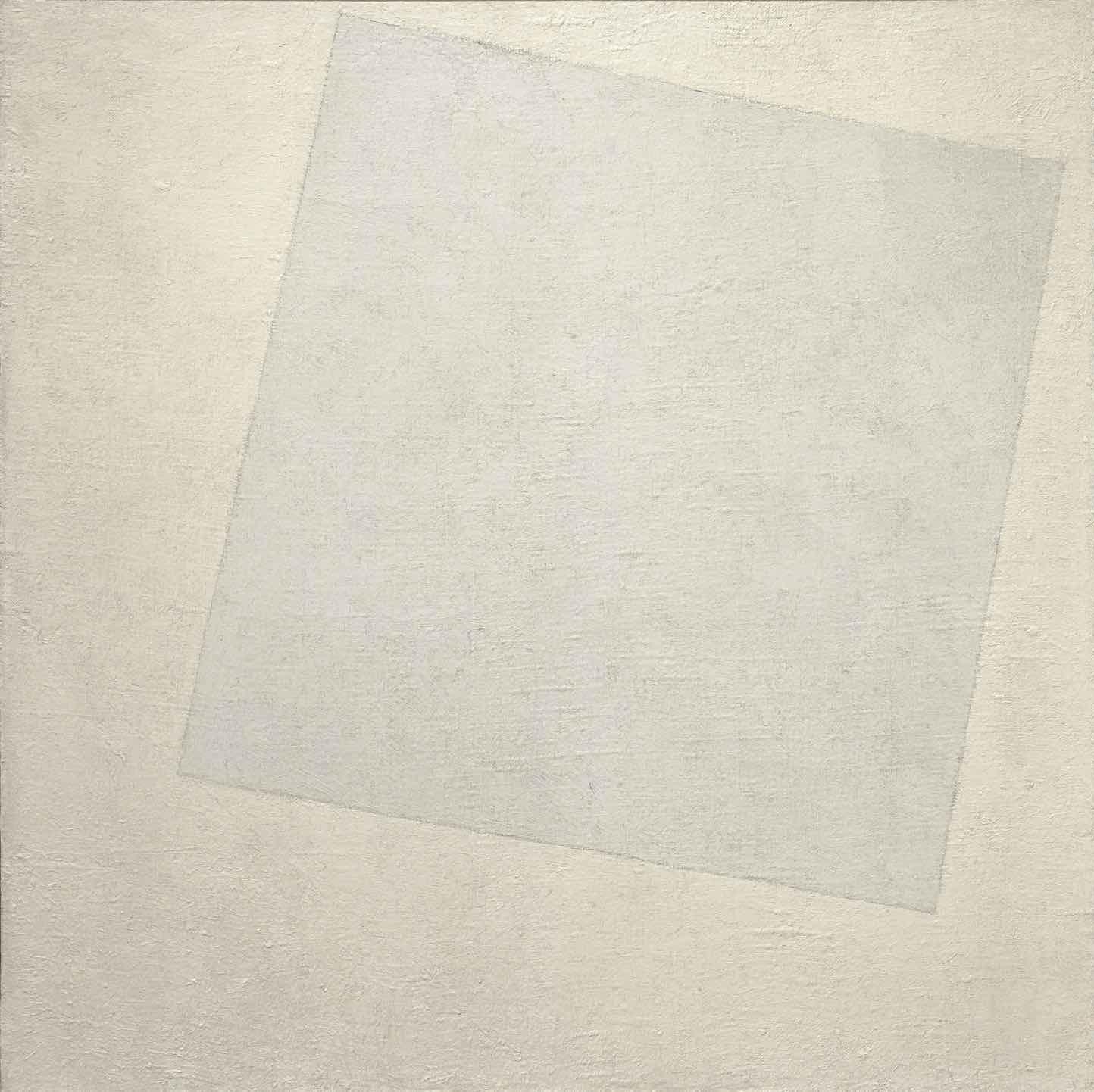

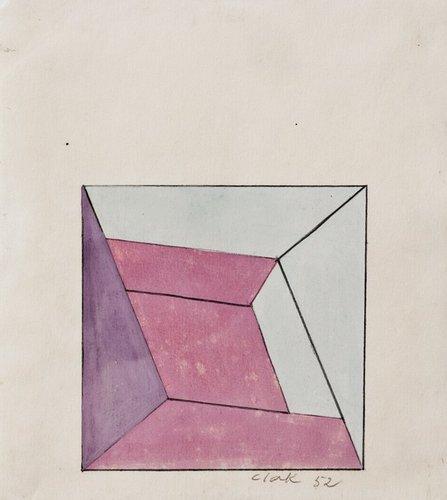

In 1930, the Dutch artist and leader of De Stijl Theo van Doesburg coined the term, Concrete Art. Riding on a wave of post-war euphoria, in thrall to science and industry, artists like Netherlandish painter Piet Mondrian, Russian constructivist El Lisitski, and Ukrainian-Russian supremacist Kazimir Malevich all practiced the art of reduction.

As a group, they made art without reference to nature. It was Malevich who brought the art of elimination to its logical extreme in Black (1915), his oil painting of a square, and in his slightly more complicated painting of two squares in White on White (1918).