A month into the Spanish Civil War, on August 20, 1936, Francoist forces reported that the world-famous painter Igancio Zuloaga had been assassinated by the Republican army in Madrid. The news made headlines in the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, and all over Europe. Zuloaga was actually in France at the time, but the false reports succeded in distracting from the real murder of the renowned poet Federico García Lorca by the Fascists two days earlier in Granada. On March 7, 1937, Francoists falsely reported that Zuloaga had been killed by the ‘Reds,’ this time in Bilbao. Again, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Los Angeles Times lamented the senseless murder of Spain’s most admired and representative painter.

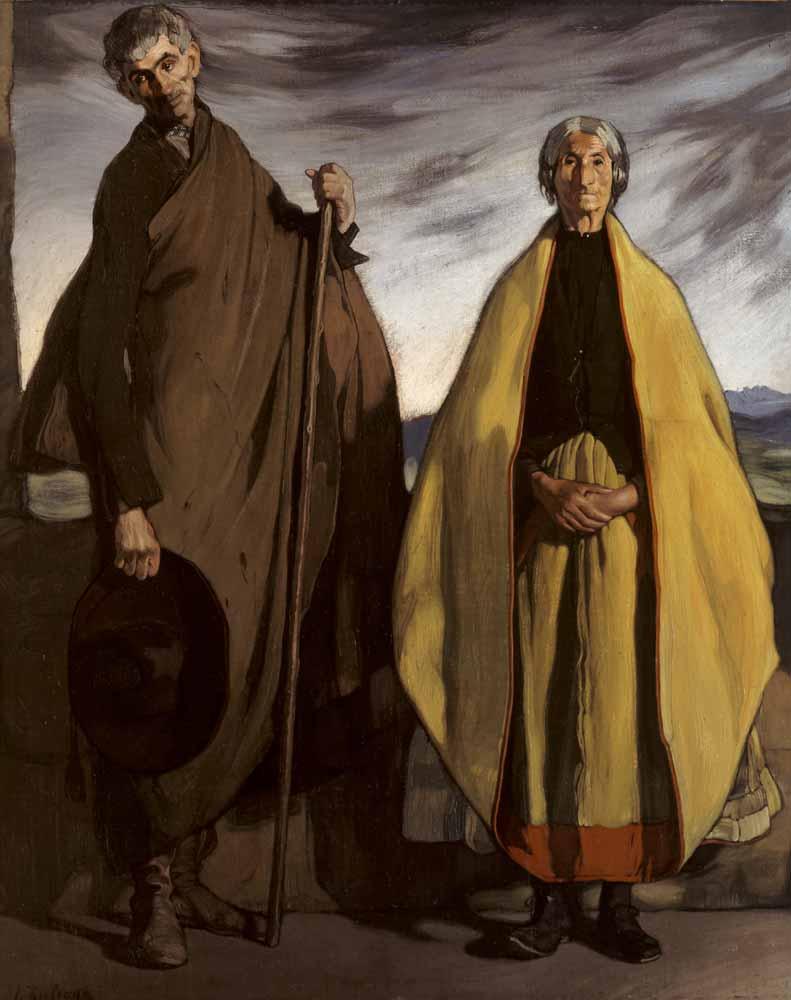

From the beginning of the conflict, Zuloaga was invaluable to the Fascist propaganda machine. But before the Civil War, the painter had spent the majority of his life rejected and ridiculed by audiences, critics, and institutions in his homeland. Zuloaga: 1870-1945 at Bilbao’s Museo de Bellas Artes explored how the painter went from innovative exile to national emblem in the course of his career.