The pleasure of retrospectives is that they allow us to go deep into an artist’s singular development, but the danger is that arranging an artist’s work in retrospective sets that development out in such a neat, pre-ordained progression that the very nature of the arrangement separates an artist from his influences and the iterative process of making art in the first place. The limits of such a panoramic view of an artist’s work has the unintended consequence of flatting out the turns of influence and experience that shape what and how an artist sees and makes.

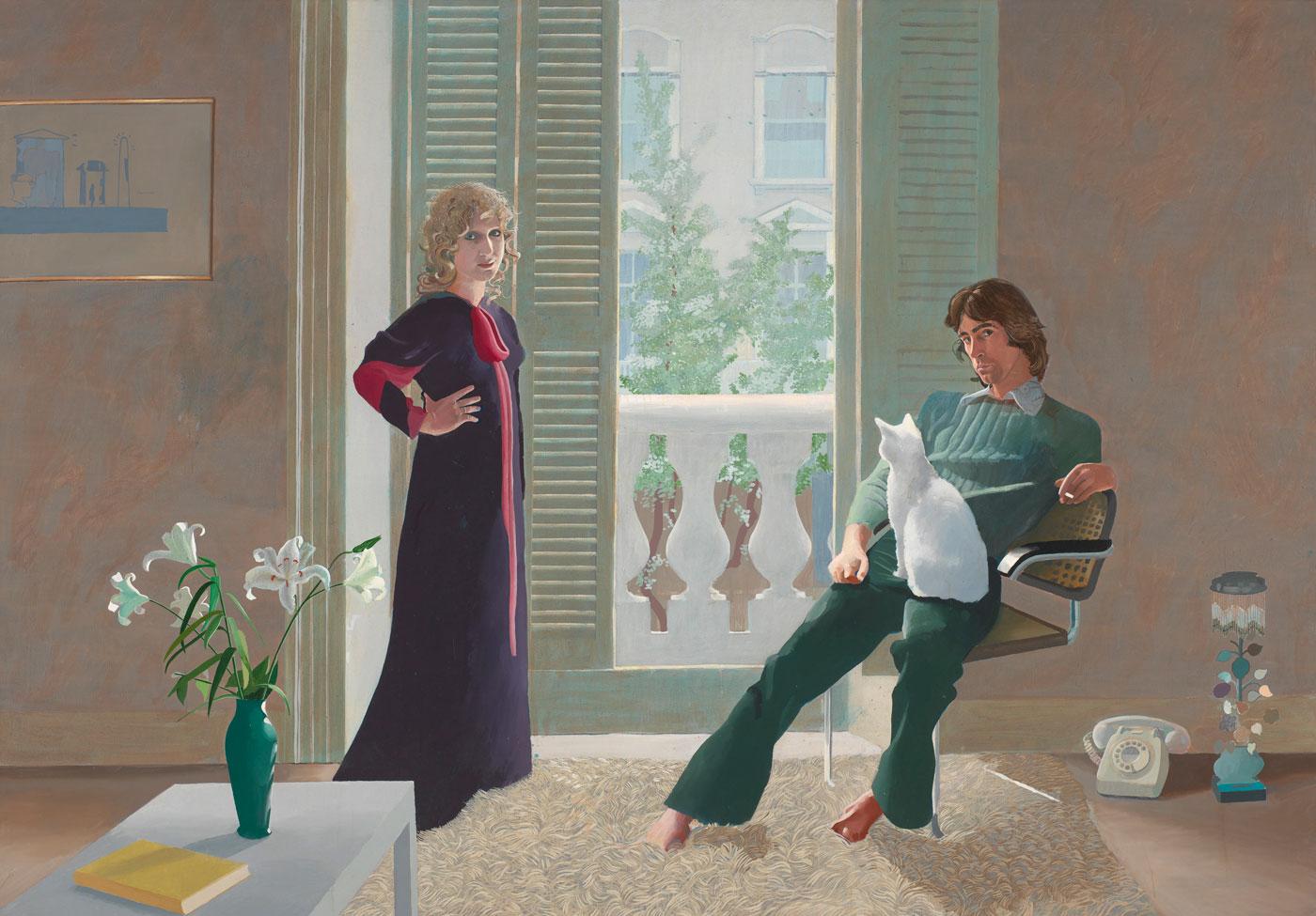

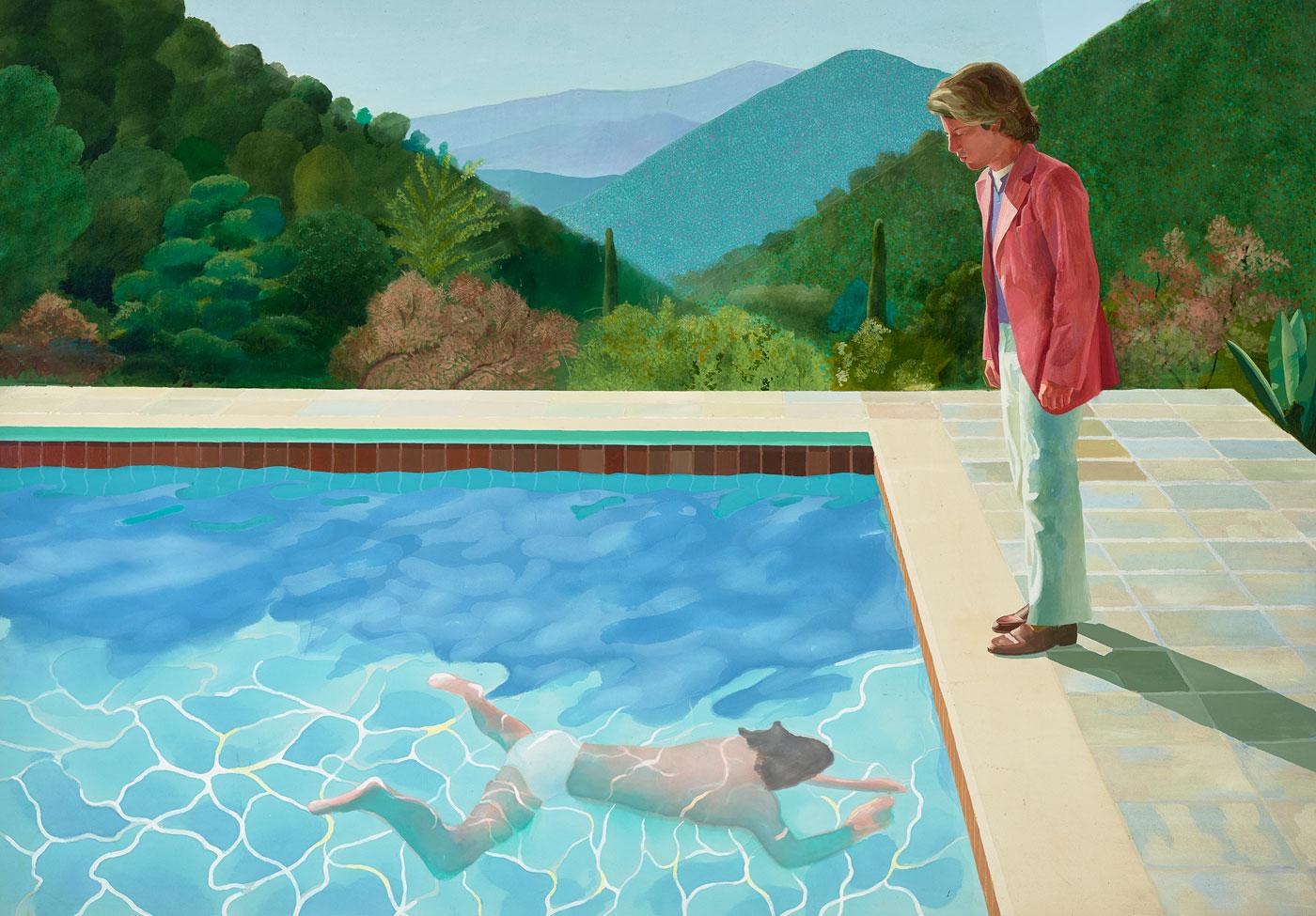

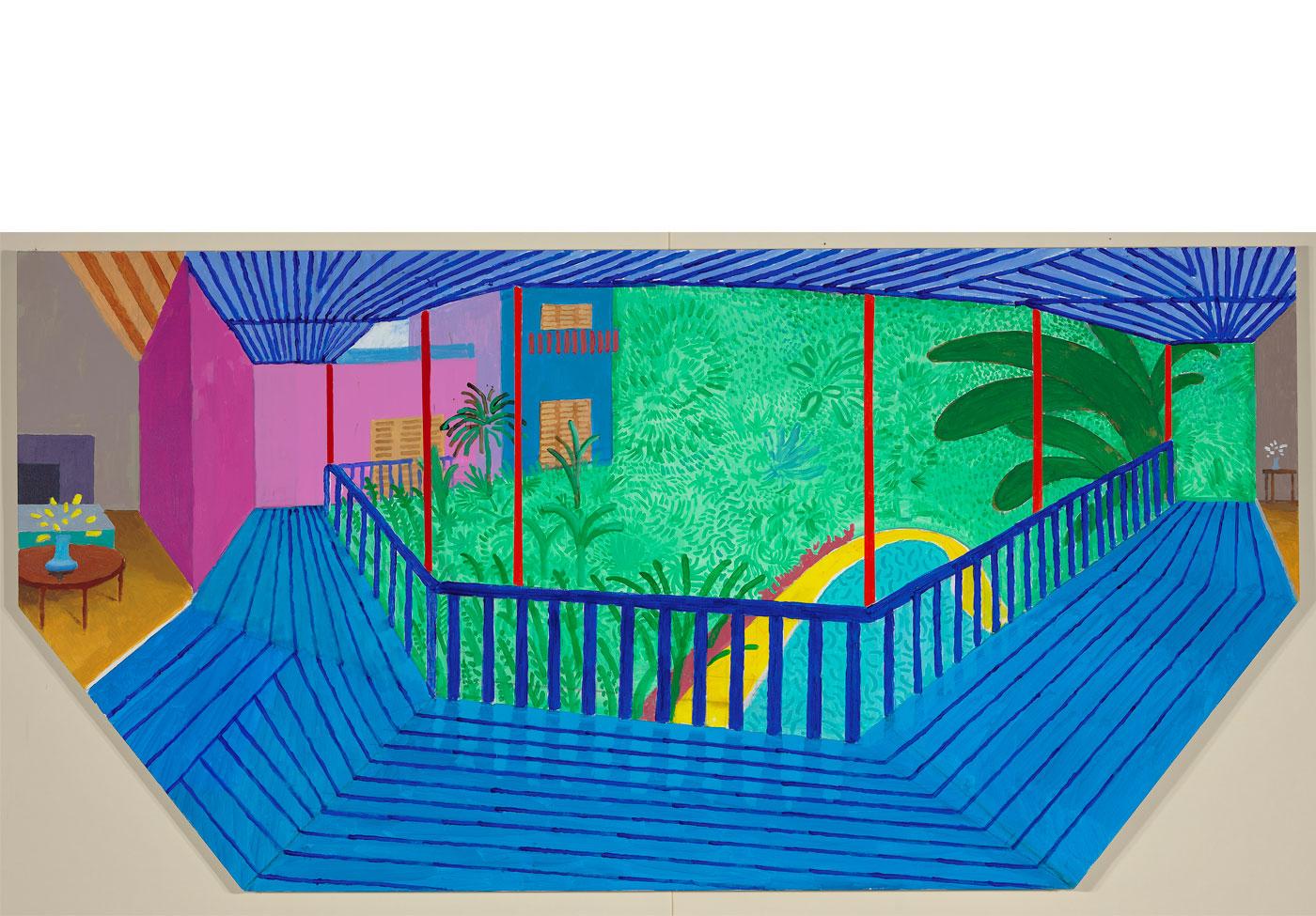

The Metropolitan Museum of Art's 2018 sweeping David Hockney retrospective was an extended meditation on what style means in modernism, and in particular what it means to Hockney. The vast span of his work demonstrates his utter originality as an artist and yet at the same time his various bodies of work bear traces of influence, not only from how he’s looked—and what he’s looked at—but how he has observed his own experience.

One theme of the show was Hockney’s sustained engagement with what he would call “the history of pictures,” which is the title of the book he co-authored with critic Martin Gayford in 2016. By pictures he means something distinct from art history—a history of images that includes high and low, from Disney to Caravaggio. In the pages of The History of Pictures: From the Cave to the Computer Screen, Hockney writes that “Any picture is an account of looking at something.” One way to see David Hockney is as a chronicle of what David Hockney has thought worth looking at.

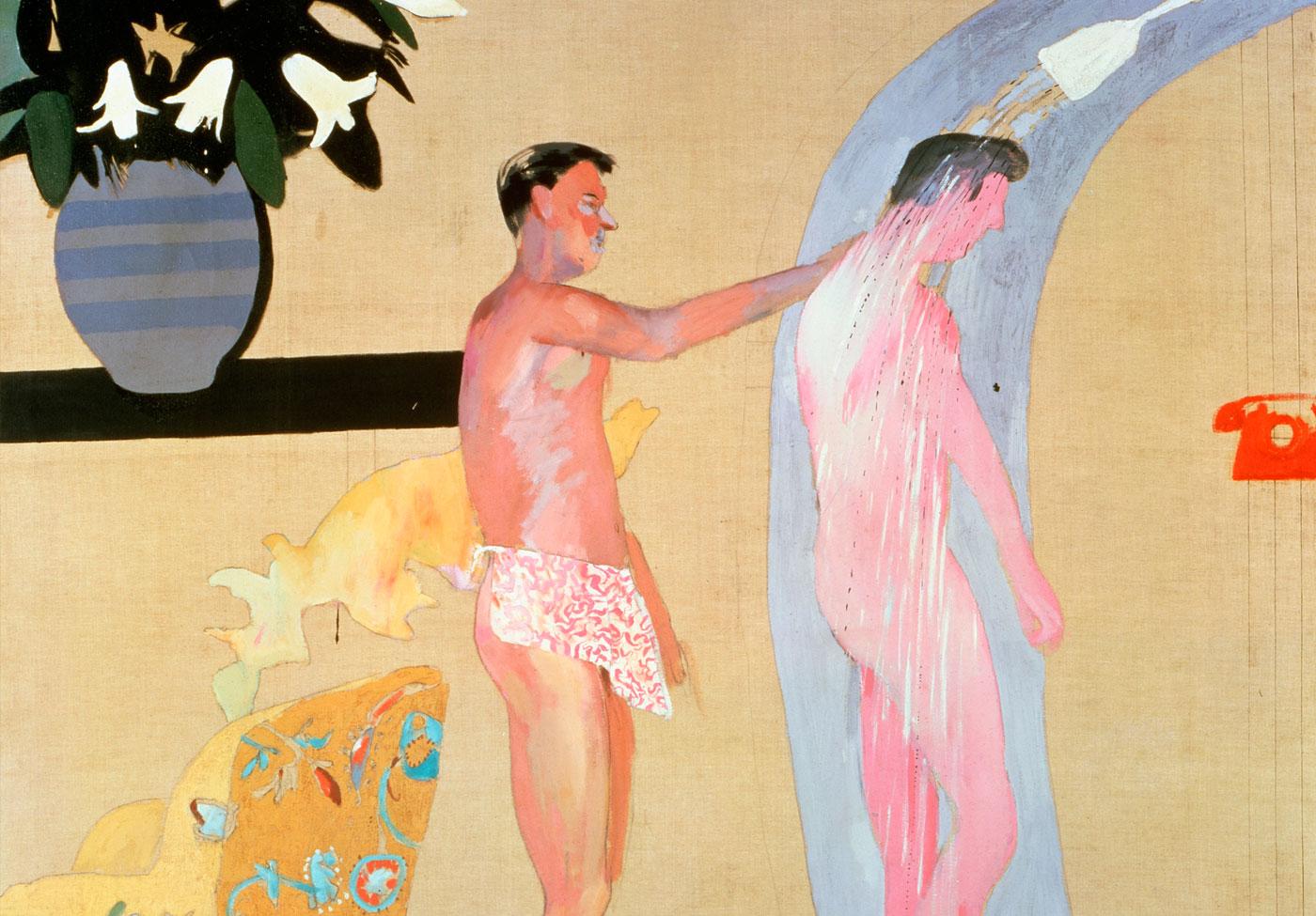

Like all retrospectives, this one began at the beginning, with paintings Hockney made while a student at the Royal College Art in the 1960s, as he creates a visual vocabulary that navigates between British art and the rise of American abstract expressionism and Pop Art. What is most exciting to see in his progression is the way he has moved between styles to create a coded, and then not-so-coded, visual style of his own inspired by Picasso, Jean Dubuffet, Andy Warhol, and Jackson Pollock, to express gay desire at a time when homosexuality was criminalized in Britain.