The goddess Venus is one of the most widely represented deities in art history. “Venus is the embodiment of all facets of beauty and love, femininity. This is a complex and ambiguous character, domineering and gracious, dangerous, and attractive. Speaking of Venus not as a character, but as a power, its dominance is even more justified,” says Anna Berkutsia, the digital curator behind the popular Instagram account @mythology_in_art, which, over the course of months, examines individual deities and mythological themes covered by artists.

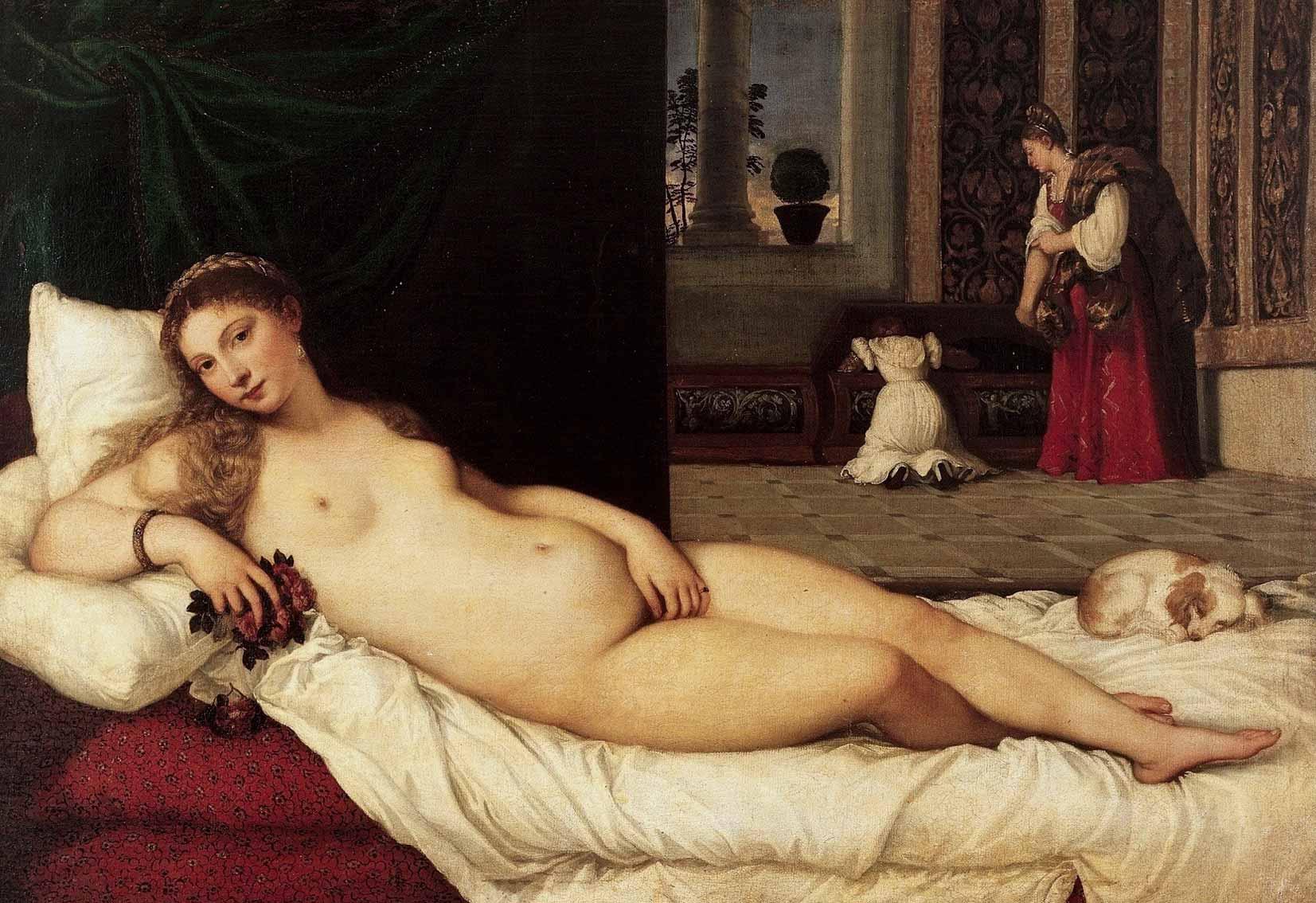

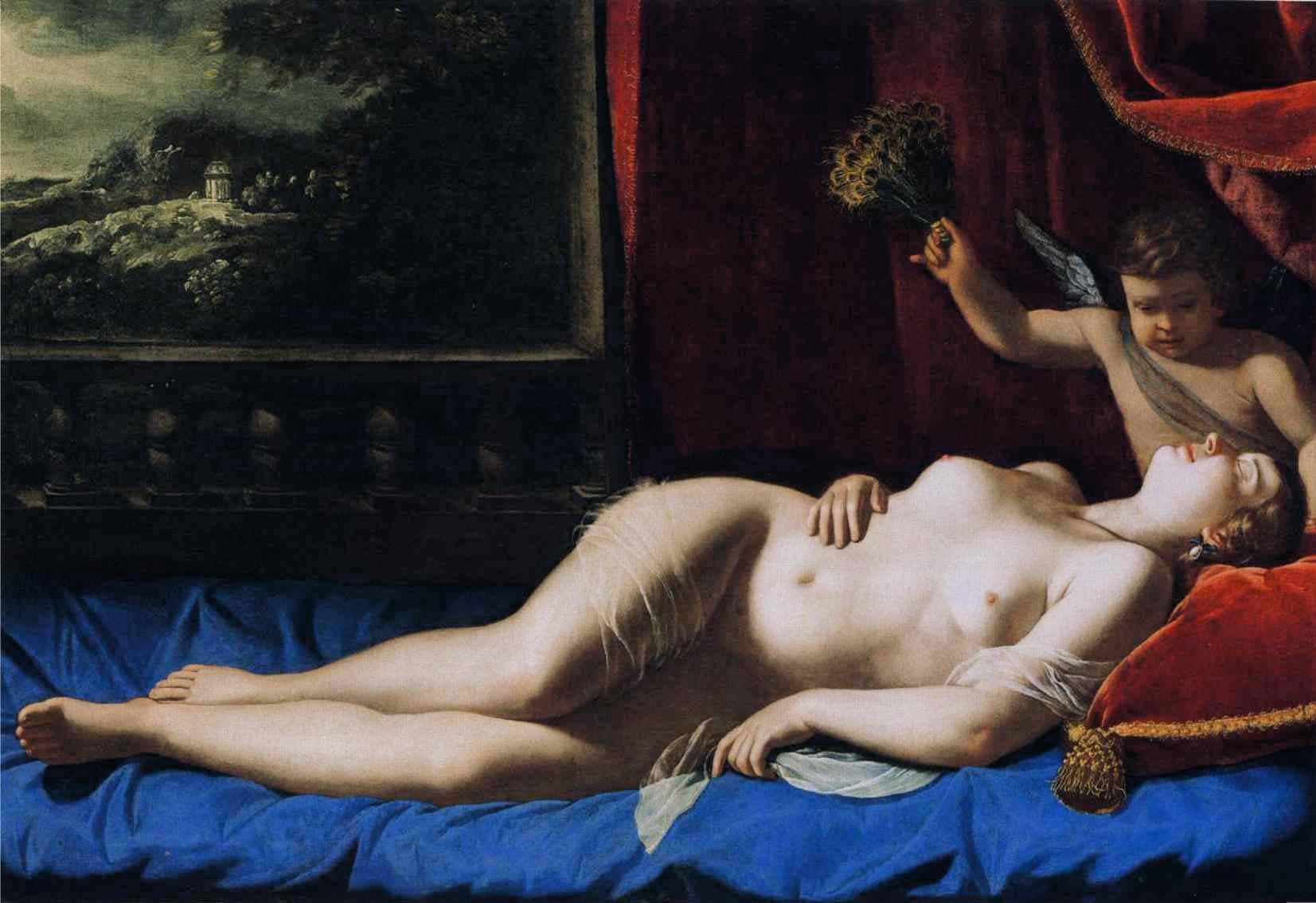

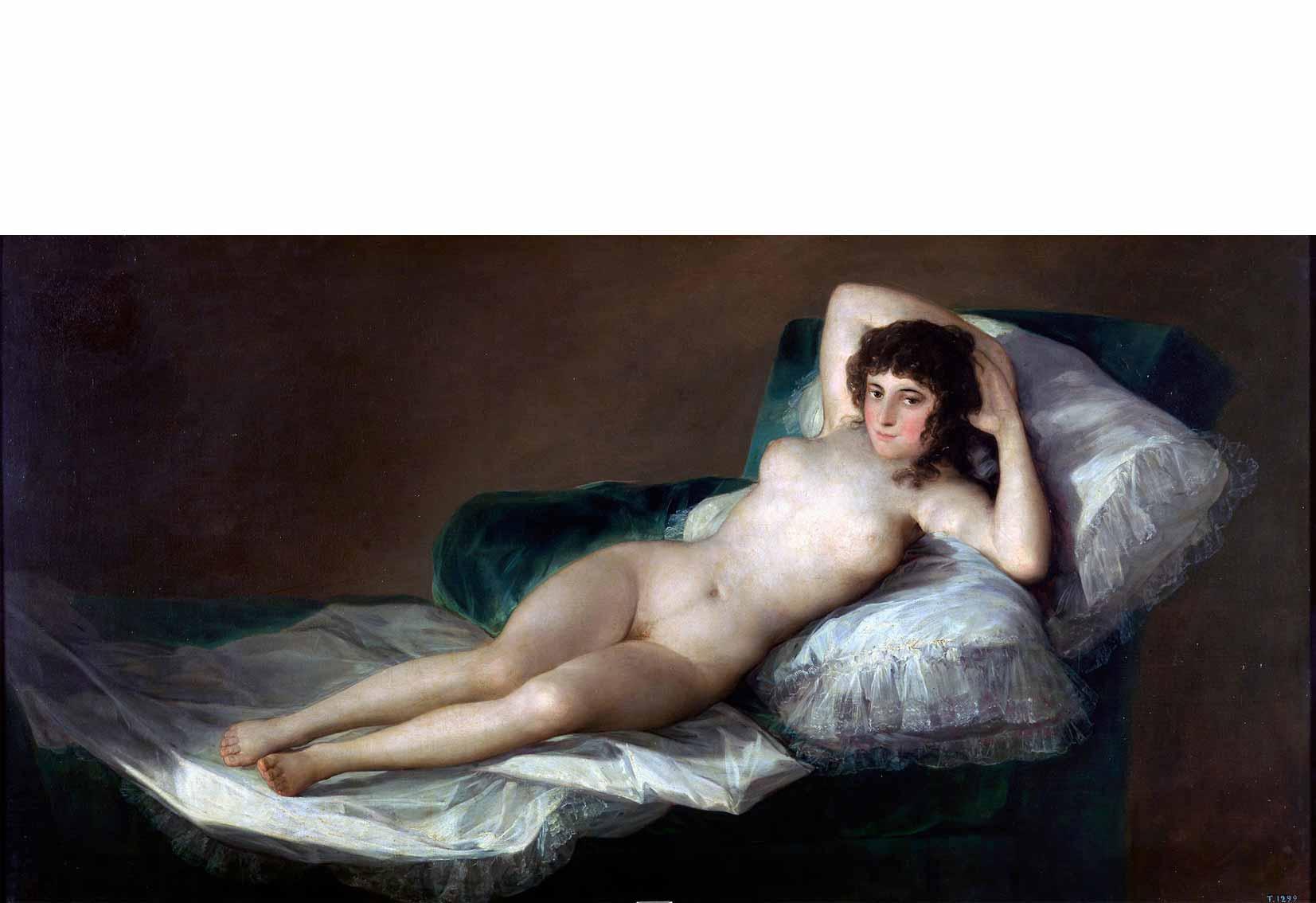

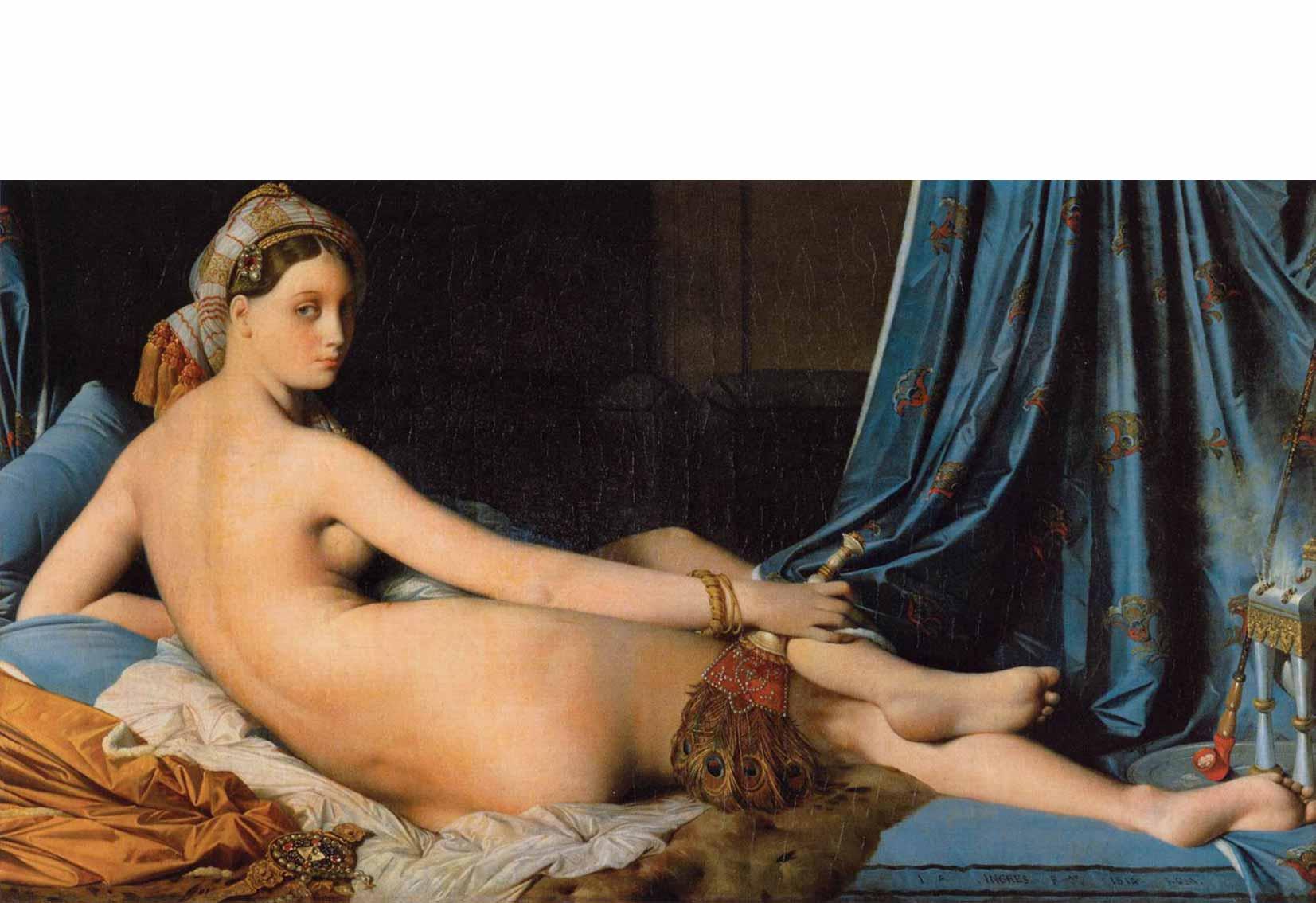

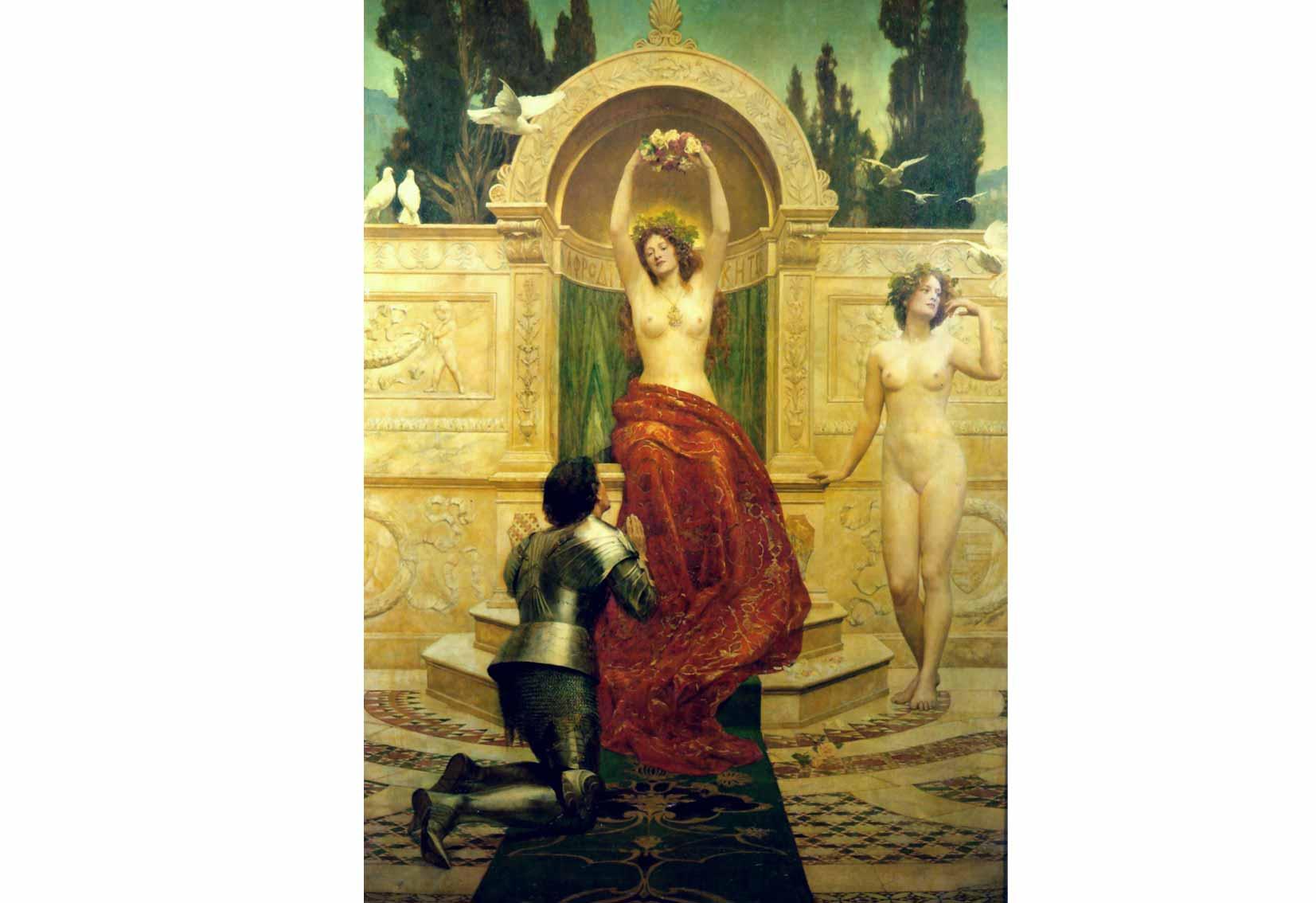

“I believe that the tropes [of Venus’ representation] are closely related to the cultural components of each time period which determine which aspect of Venus becomes dominant,” she continued. “The oldest statues of Venus point to the central role of fertility in the image of the goddess. Then, in Classical art, Venus became the standard of physical attractiveness and beauty. Over the course of centuries, the image of the goddess acquired new features: for example, the medieval Venus is associated with a wild and destructive passion that goes beyond matrimony and the Christian morality, as we see in the legend of Tannhäuser. In the baroque era, she is presented as more regal, with her nudity offset by head ornament and jewels.”

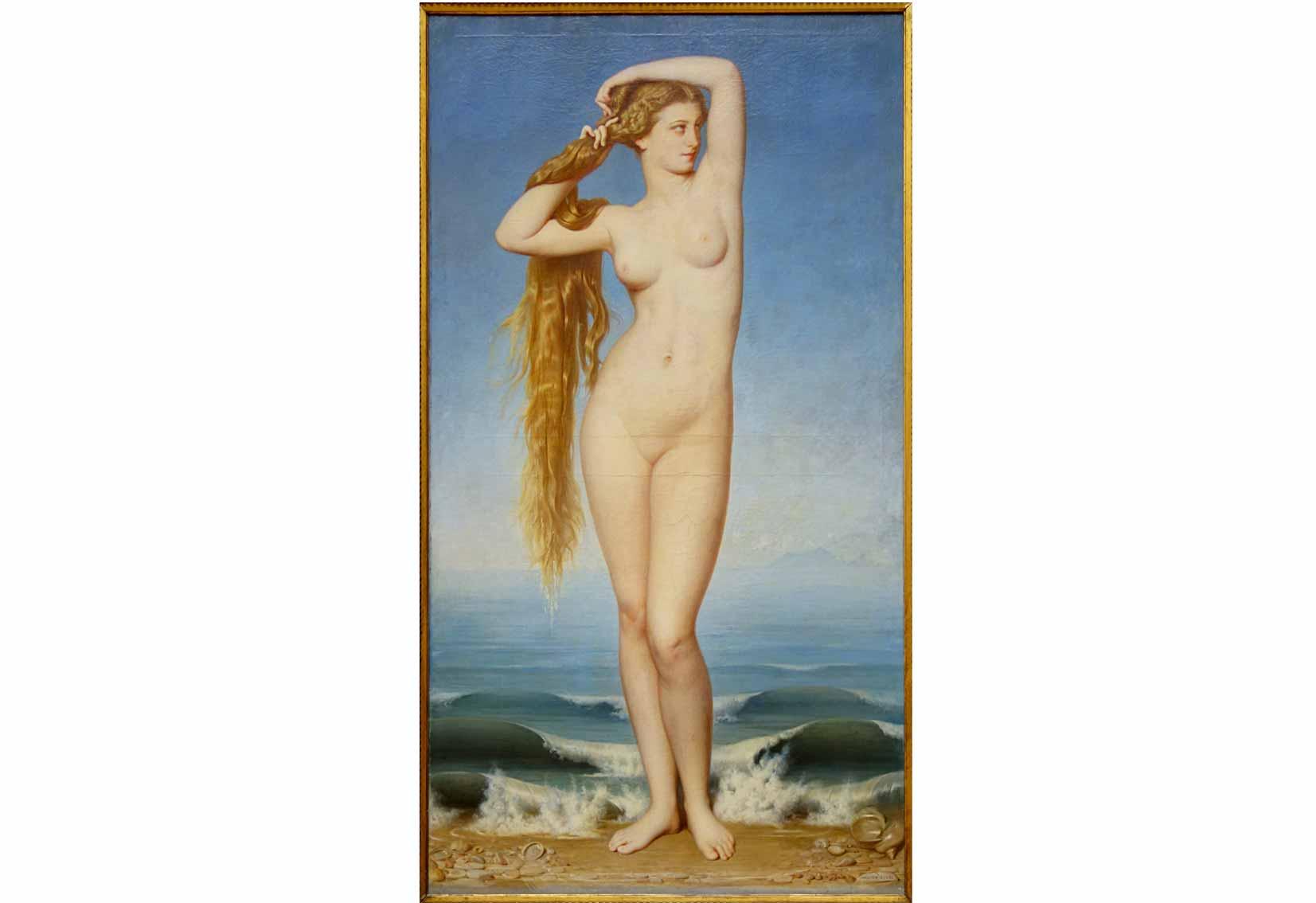

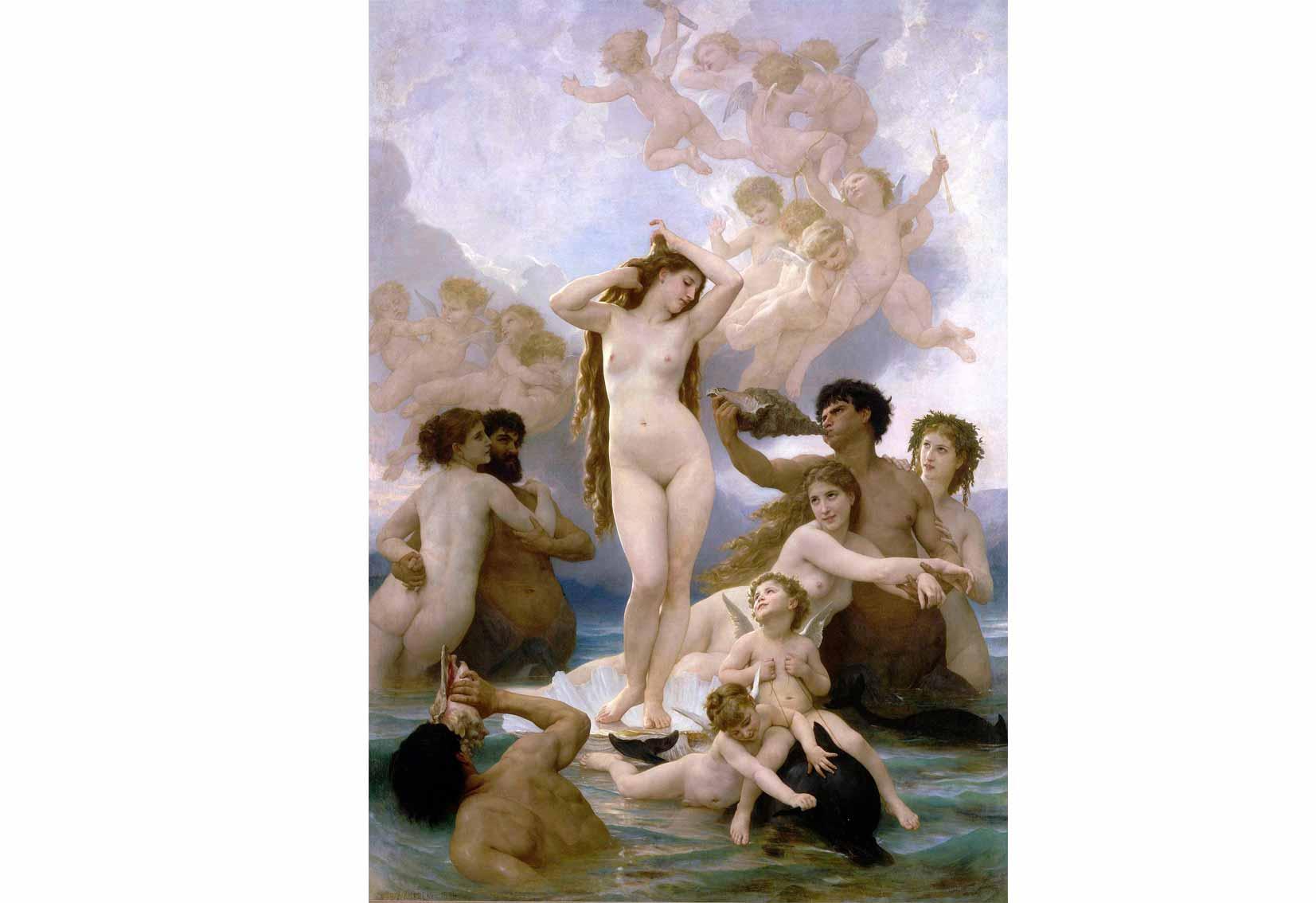

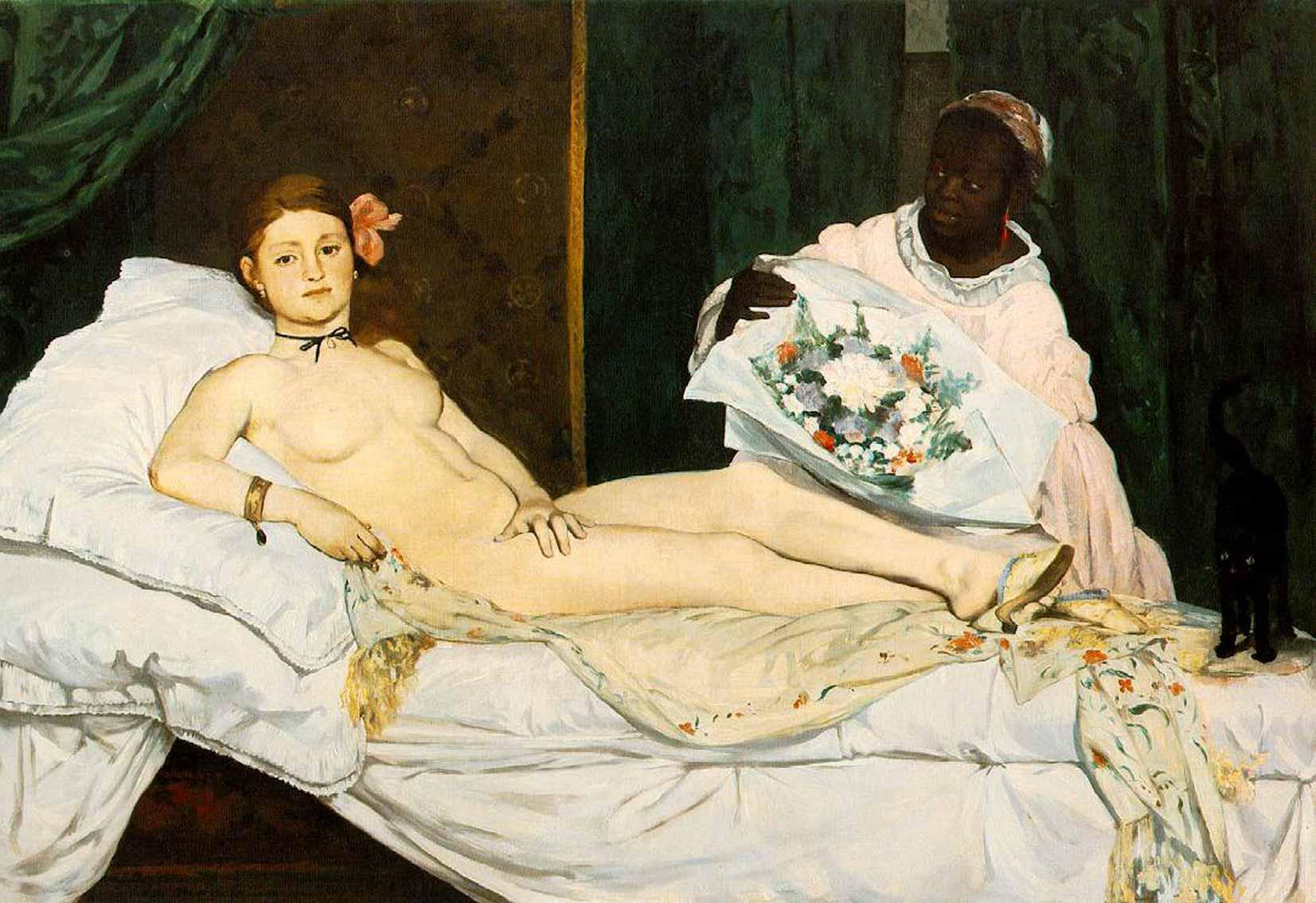

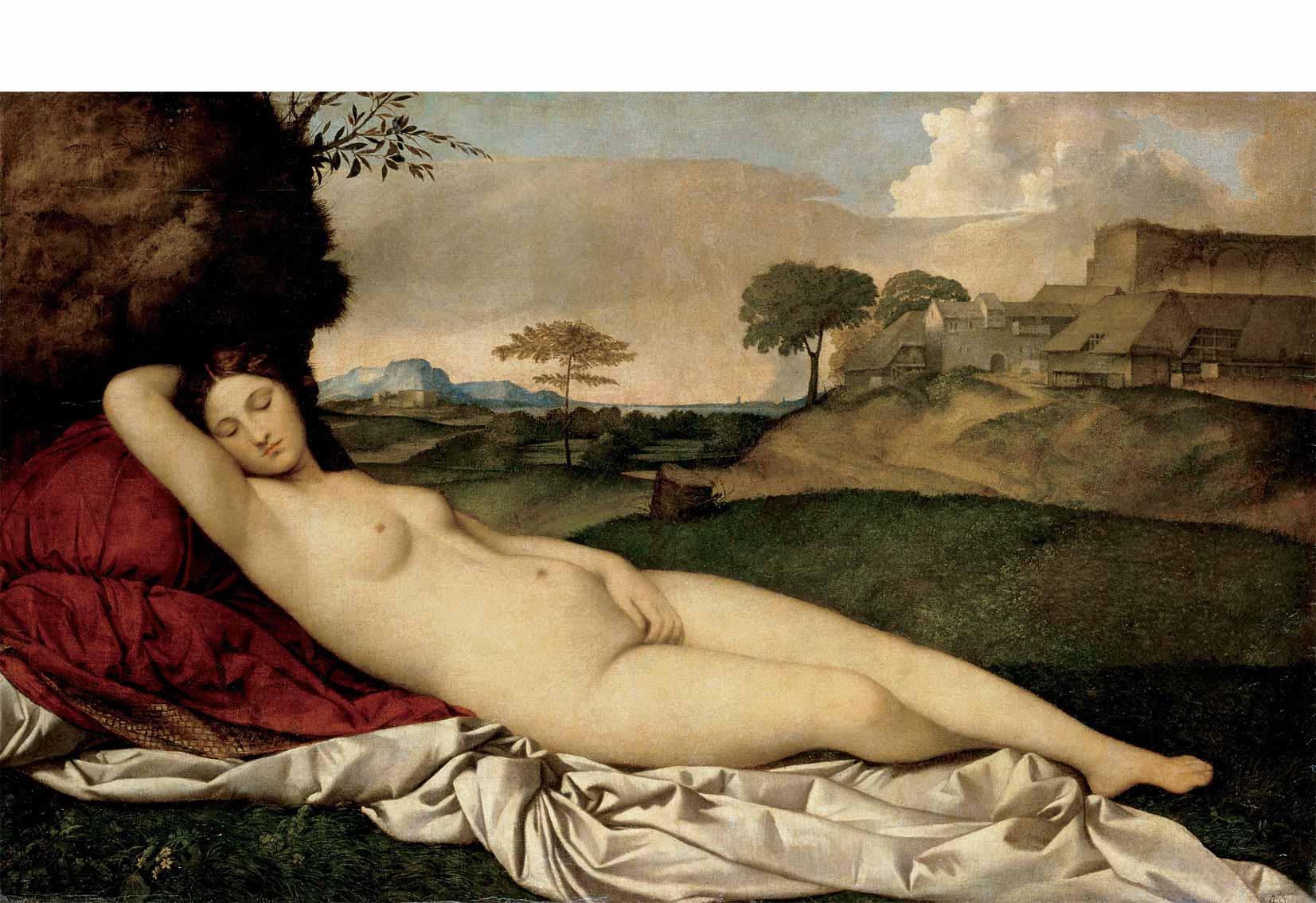

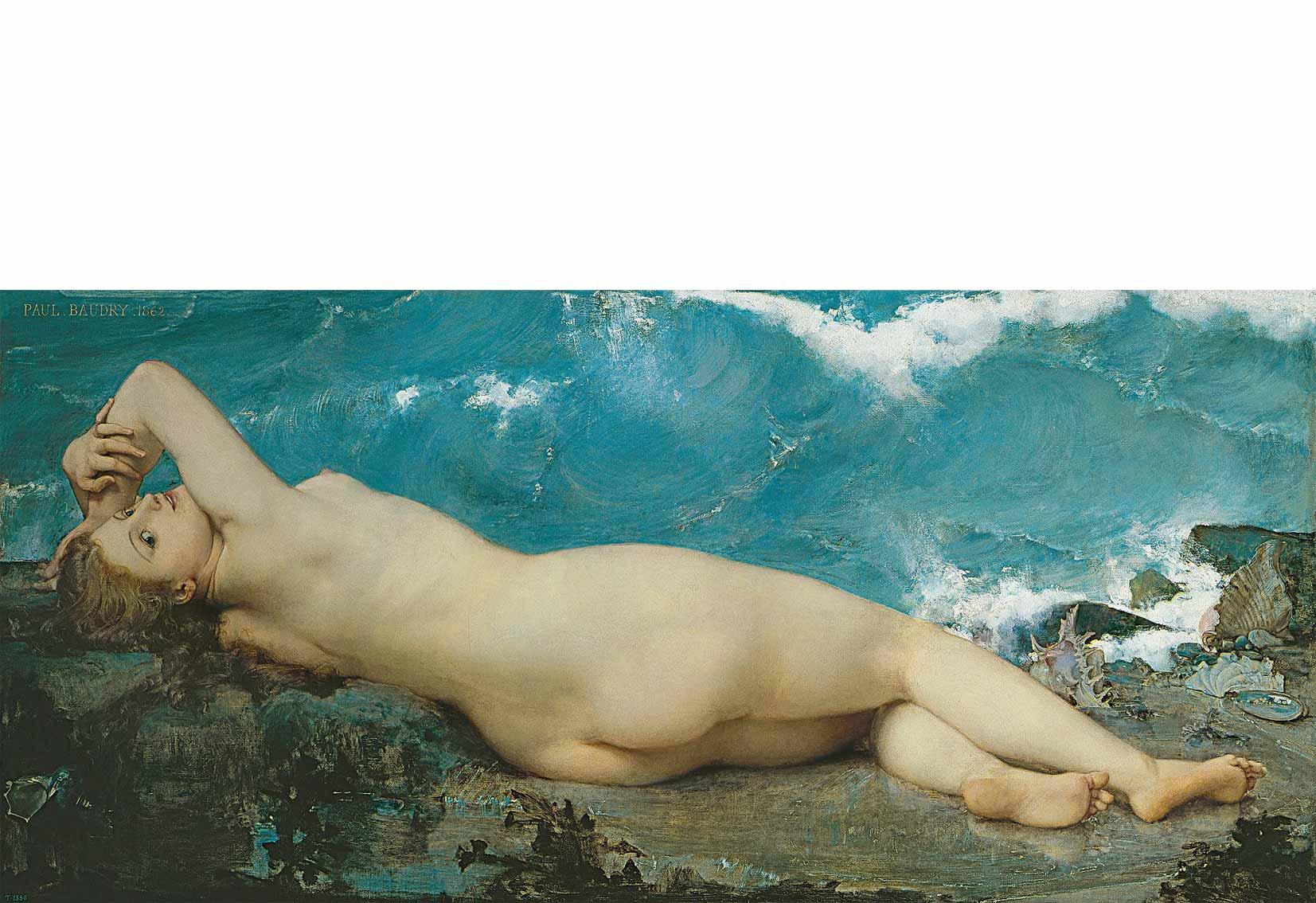

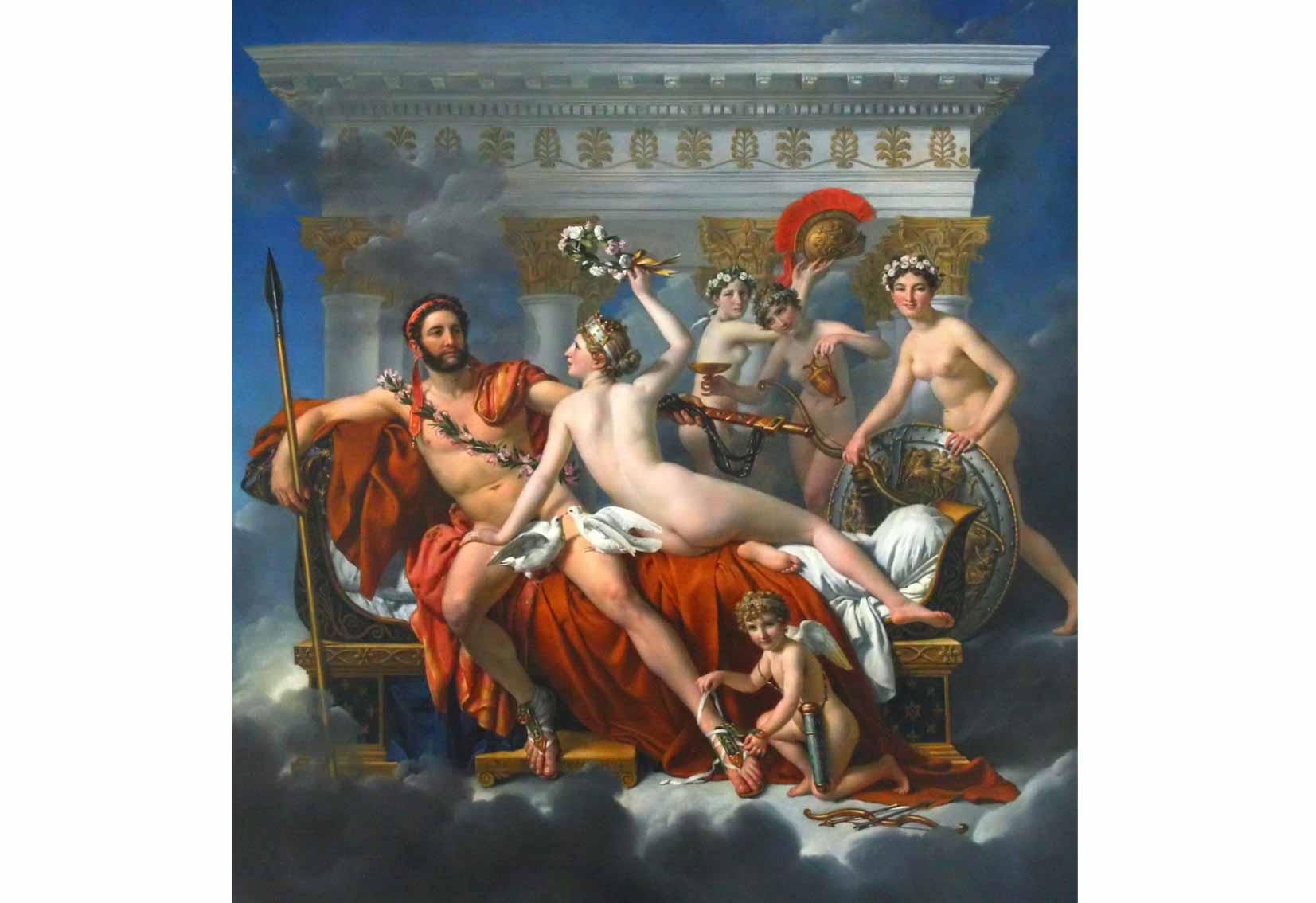

In the nineteenth century, Venus became the central figure of academic painting: the story of her birth, which took place when Uranus’s genitals were severed and thrown into the sea, which caused the water to foam and Venus to emerge, is the basis of the quintessential female standing nude. Below, we examine three of Venus’s more frequent motifs, which we acknowledge are far from a complete list of Venus’s guise: Venus rising from the sea; the recumbent Venus; and the seductress Venus, accompanied by a male lover.

Venus Rising

Ever since the fourth-century painter Apelles painted Venus in the act of rising from the sea (in Greek, anadyomene), a painting that is now lost but survives in descriptions, a nude Venus, generally in a standing position, has been the subject of painters and sculptors from antiquity into the modern age.

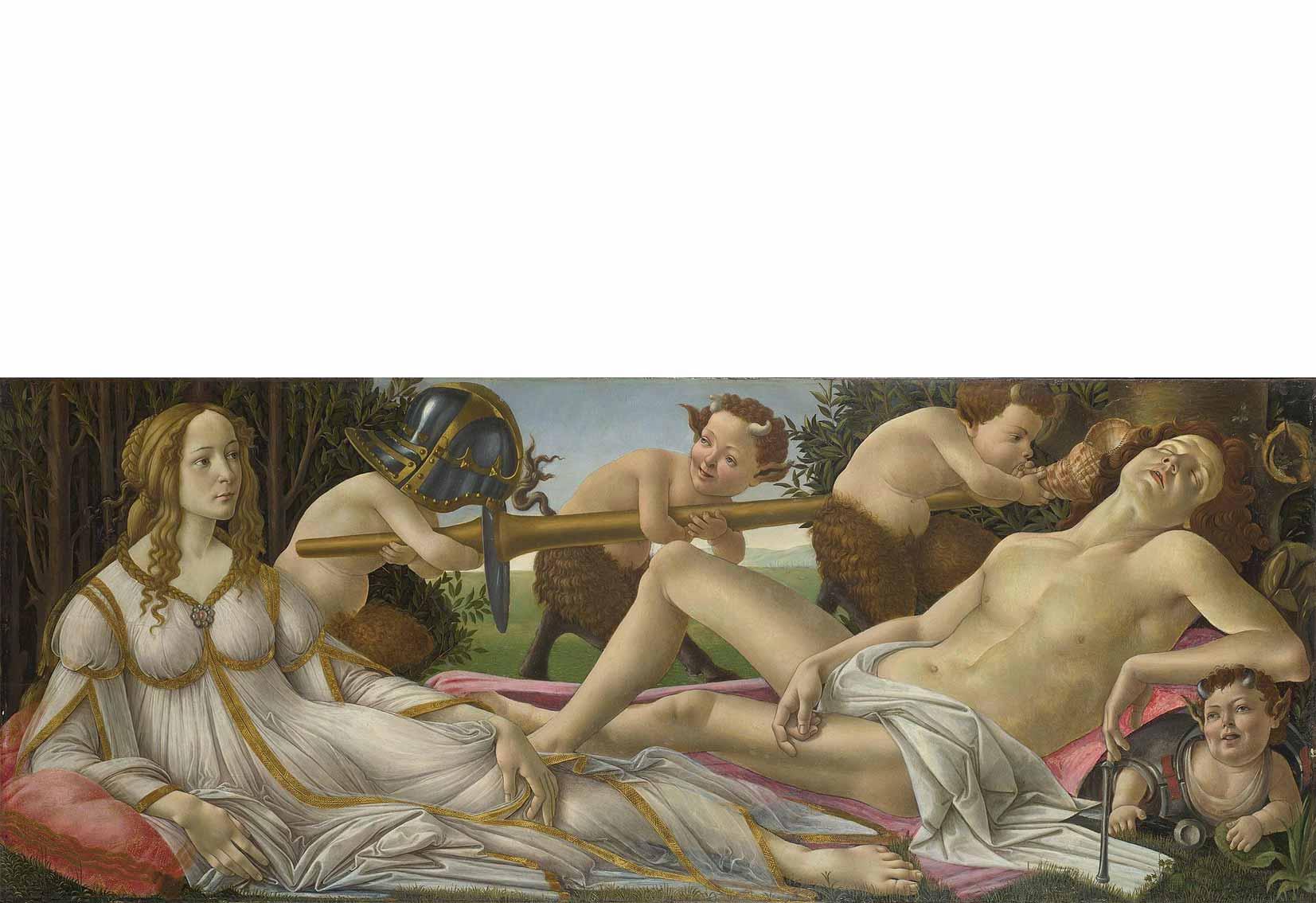

The best-known anadyomene is Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (1484–86), where she is standing on a shell and surrounded by other minor deities. Titian’s interpretation of it (1520) depicts her in the act of wringing her hair. In the sixteenth century, the simple birth of Venus transitioned to the triumph of Venus, with the goddess flanked by other creatures as she rises from the sea: the blueprint was, actually, the depiction of another deity, namely the Raphael fresco Triumph of Galatea, where the nereid is depicted in her apotheosis, surrounded by sea creatures. Nicolas Poussin’s Triumph of Venus (1635) and Sebastiano Ricci (1713) both follow this motif.