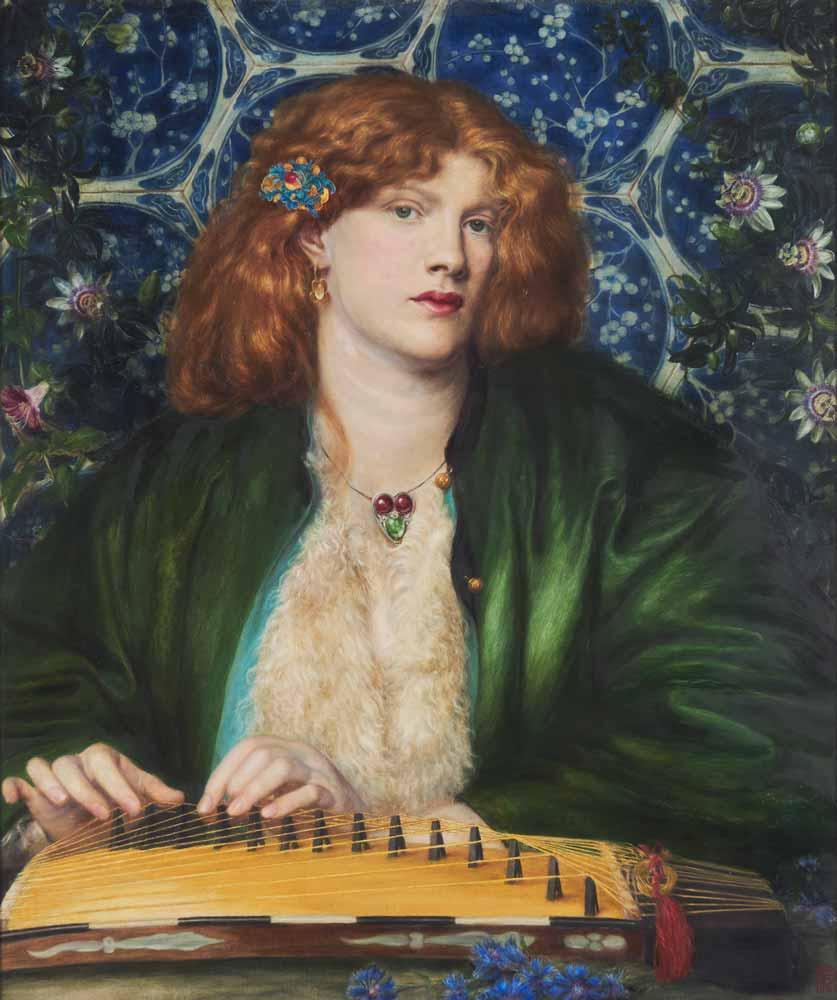

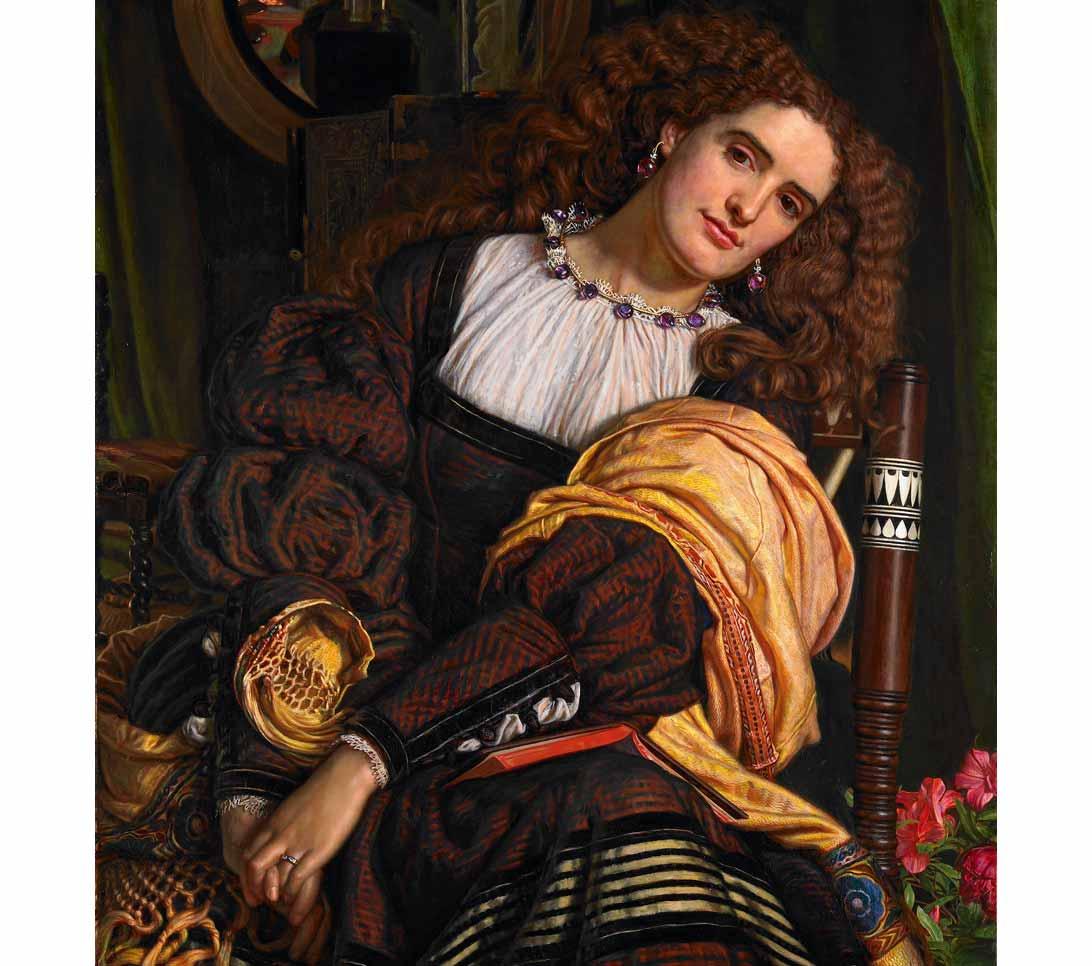

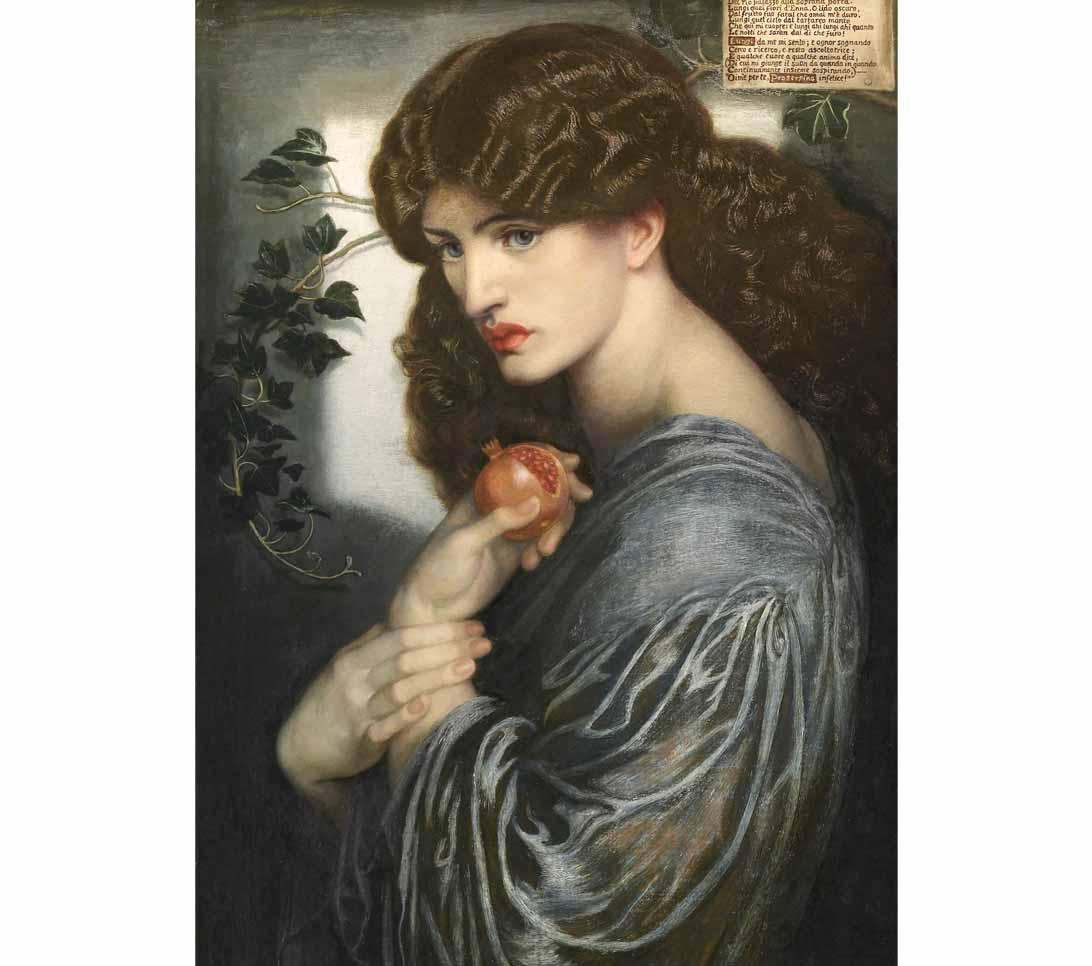

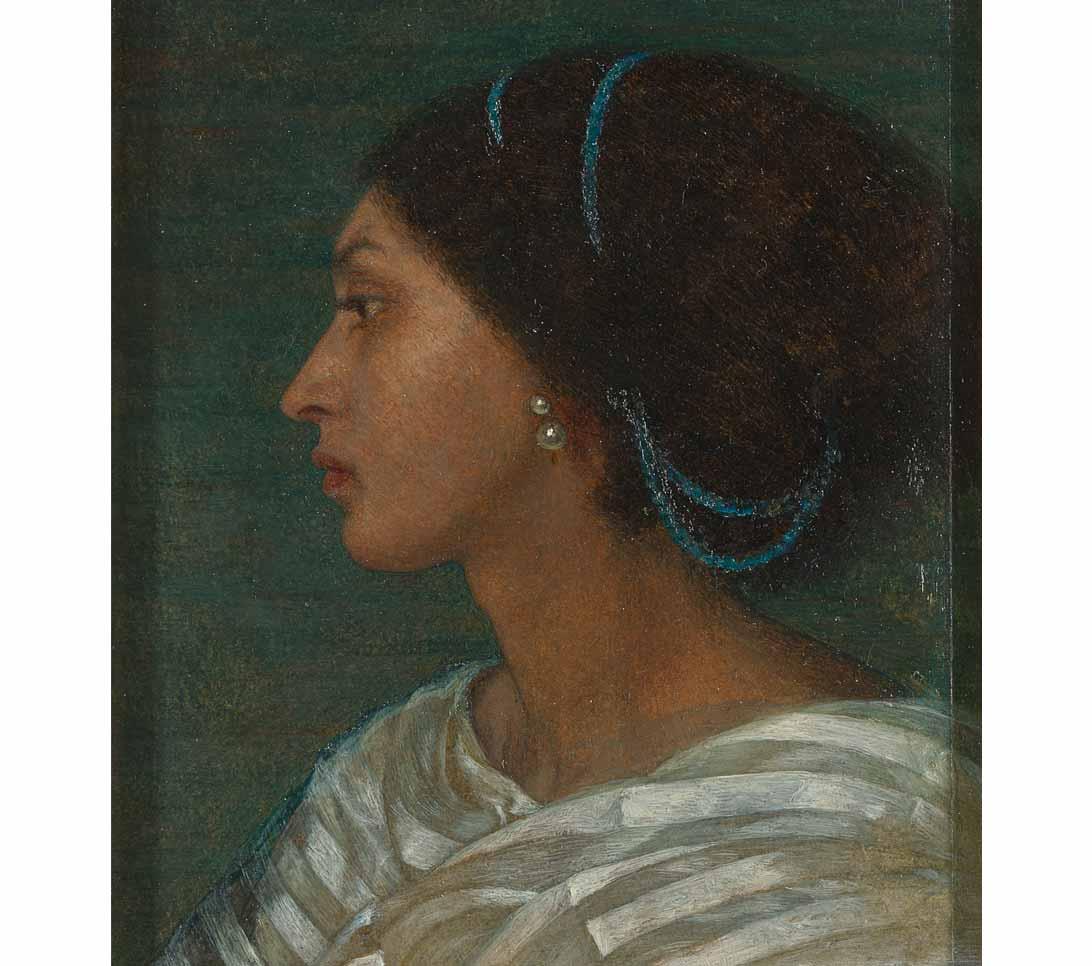

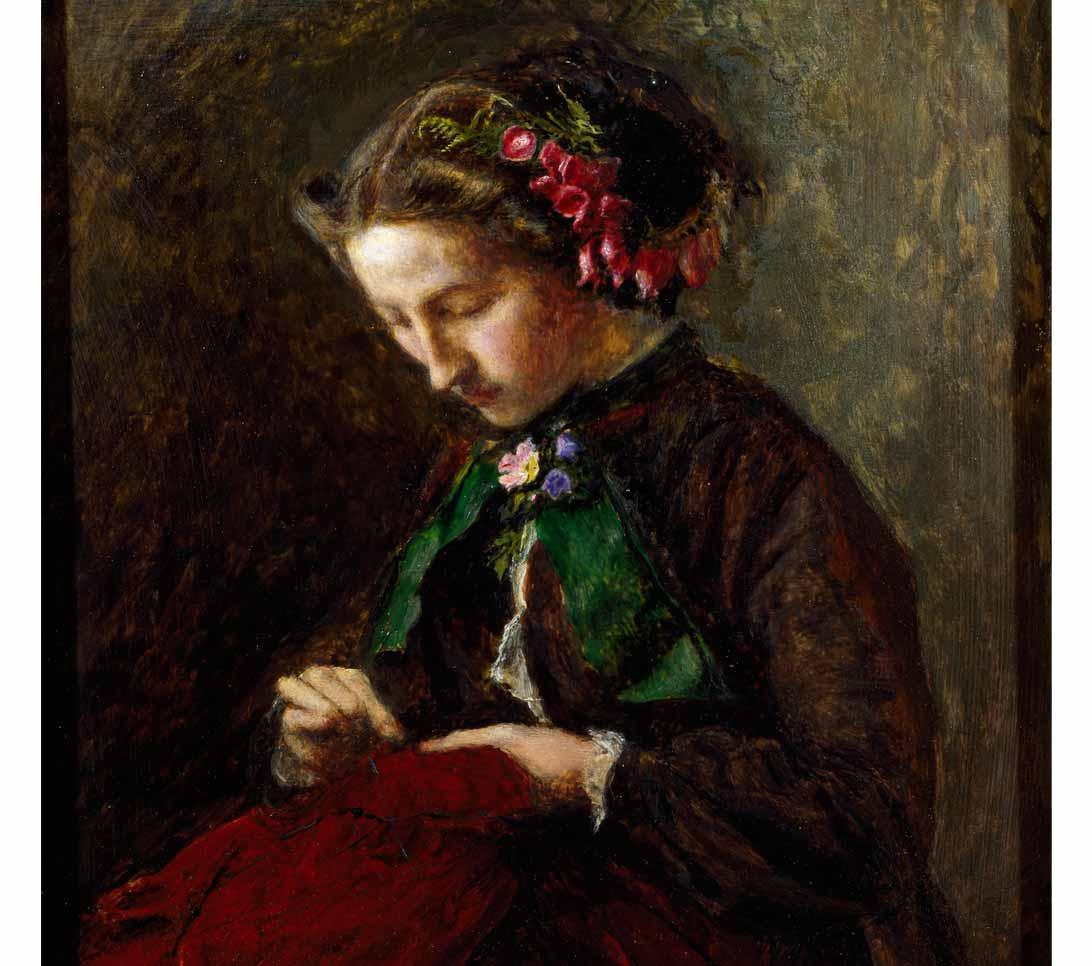

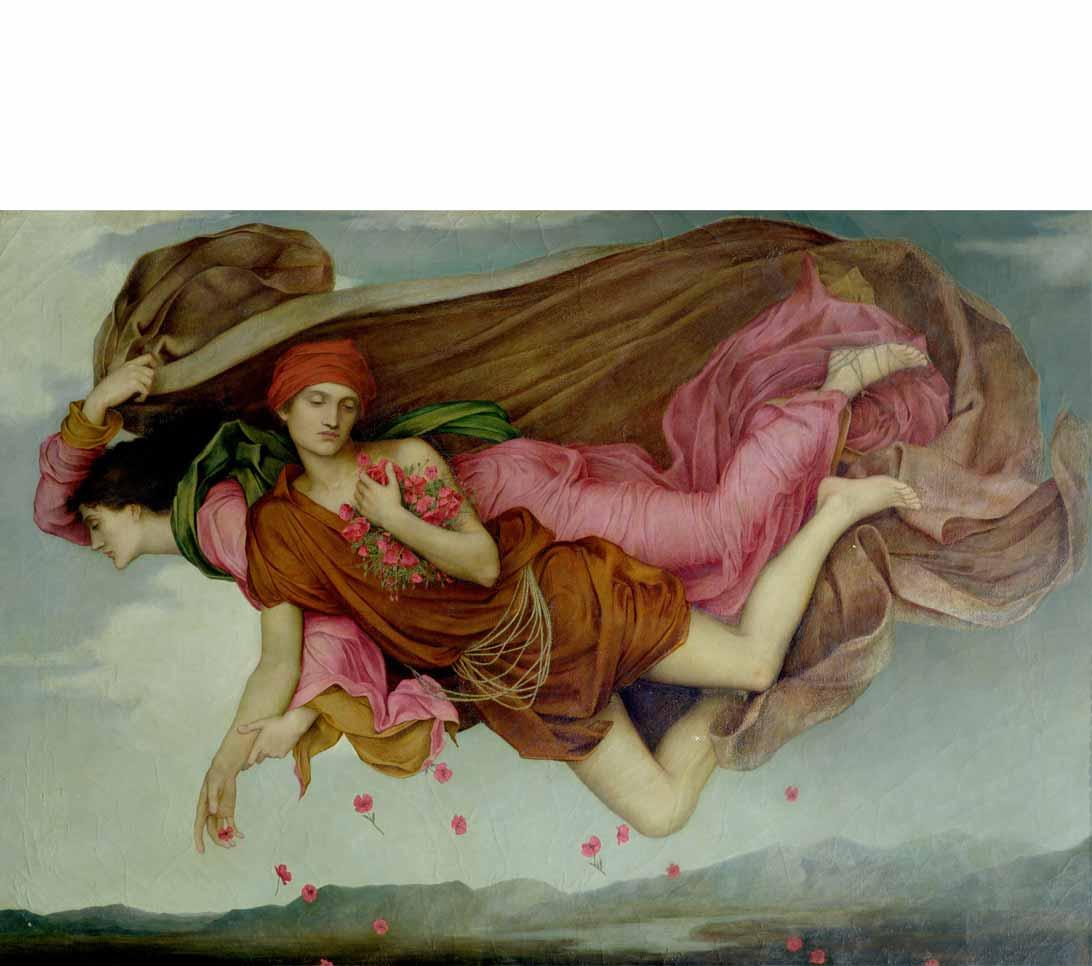

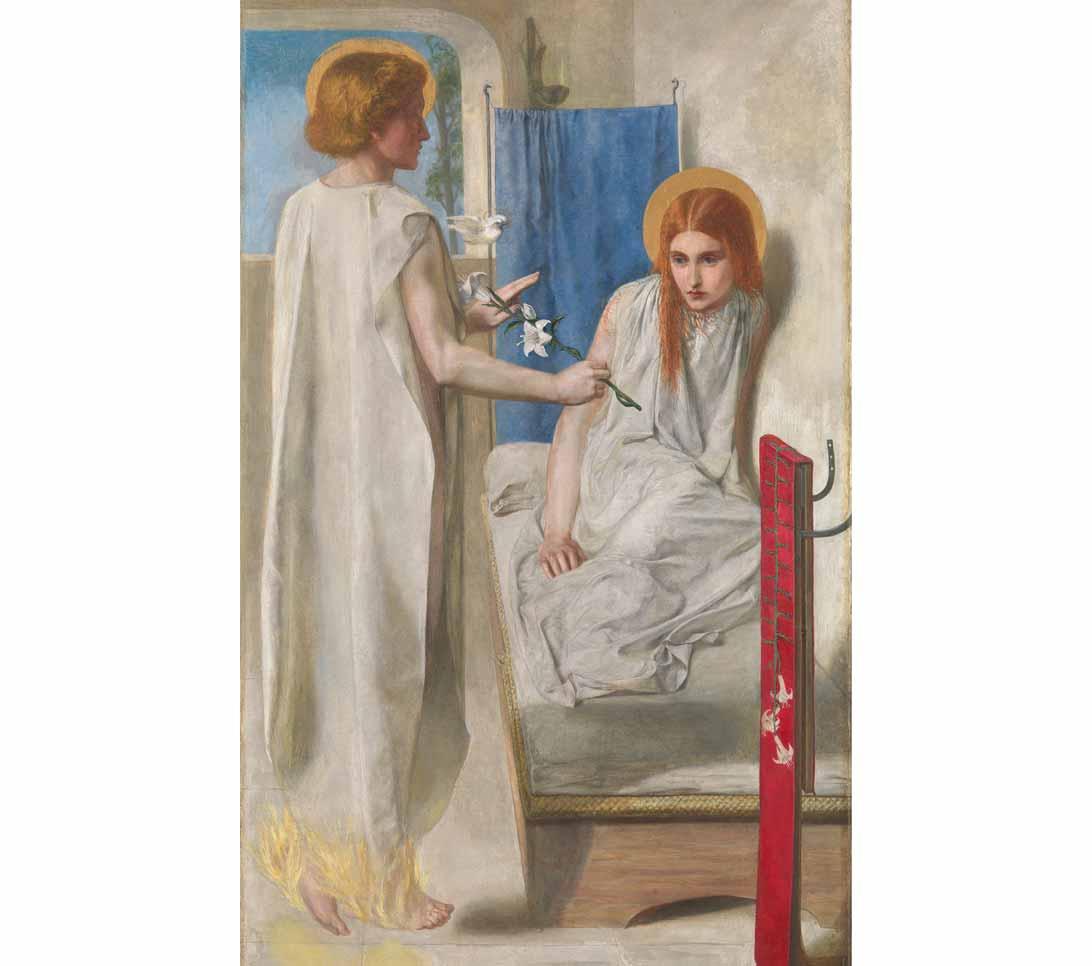

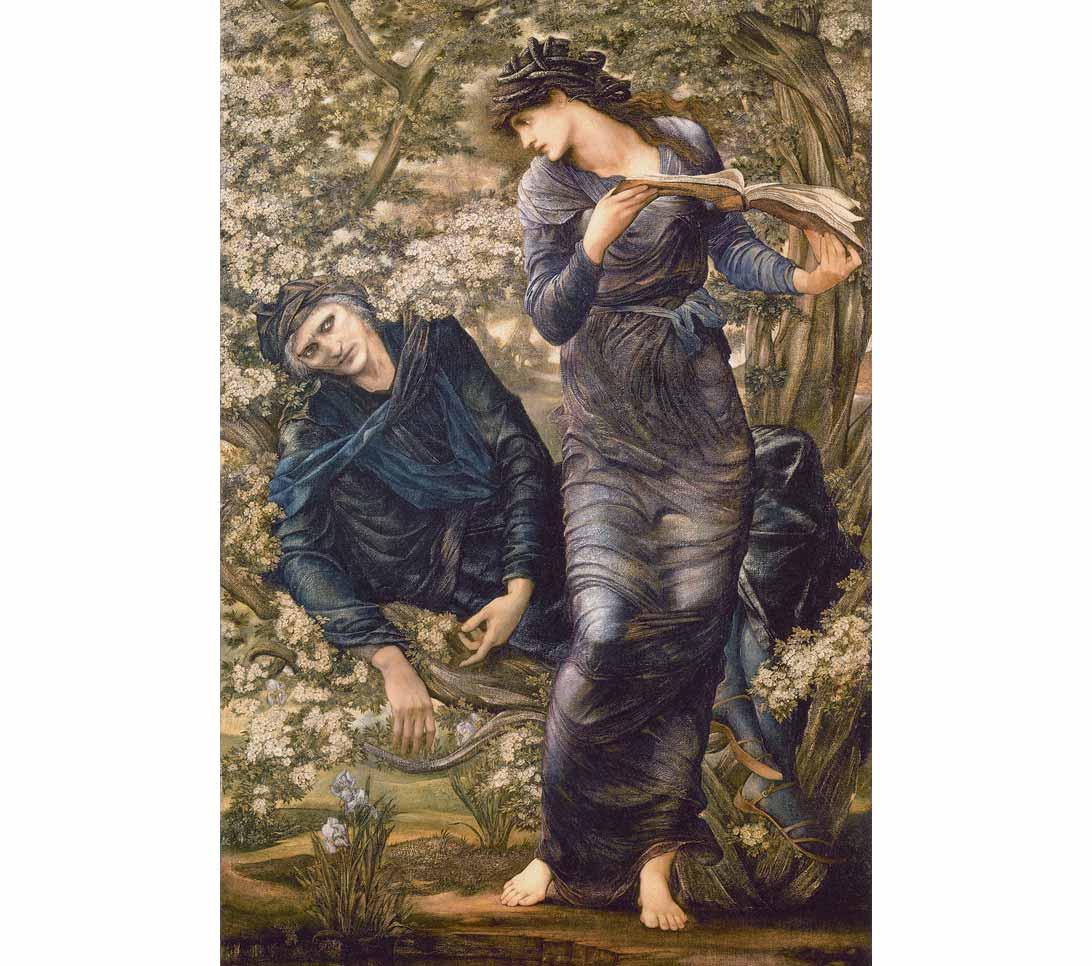

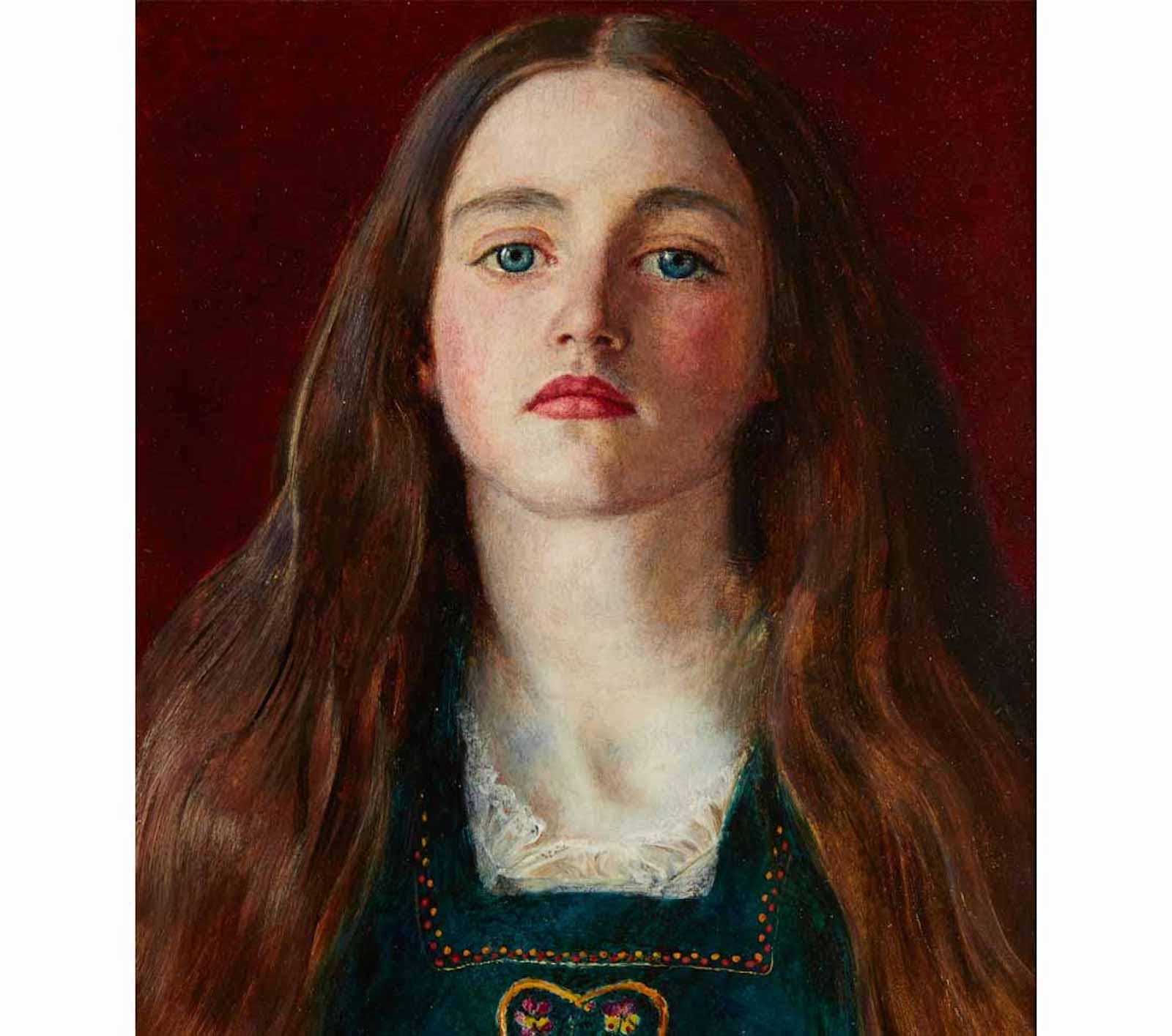

Tumbling locks, a pale complexion, a soulful gaze in the distance, and a loose gown: these are but a few of the characteristics of the women portrayed in Pre-Raphaelite art, women who, starting in 1848, would portray Biblical heroines, goddesses, historical, and literary figures.

The art and lives of the Pre-Raphaelites retain immense popular appeal, with aesthetics that are pleasing to the eyes, an utterly romantic spirit of their world and a penchant for the depiction of myths, legends, and historical events.

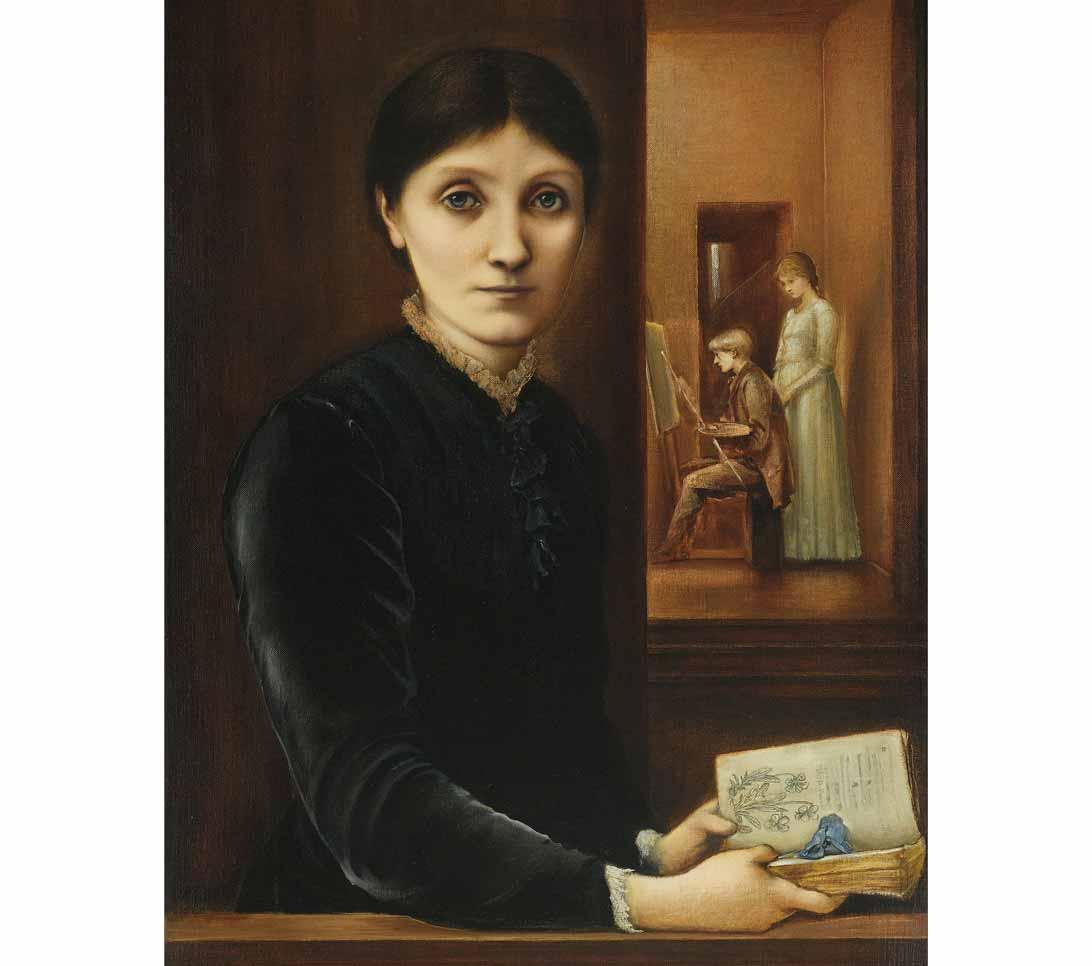

On the surface level, the women portrayed almost appear as an ornamental element, brought to the fore by the artistic genius of painters such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, Edward Burne-Jones, and their peers. However, what is oftentimes overlooked in the mystique of the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood is how much its advancement in the arts and in culture depended on the endeavors of women not only as models, but also as artists and creative partners.

Unlike most models featured in previous artistic movements, Pre-Raphaelite models transformed their own lives through active engagement in art. They became lasting celebrities in their own right, the de facto figureheads of a movement that owes much of its appeal to the beauty of the subjects that were portrayed.

“The great female models were, at the start, in the 1850s, plucked from non-artistic backgrounds because of their beauty, which did not correspond to Victorian canons of beauty,” explained Aurélie Petiot, author of the new book The Pre-Raphaelites (Abbeville Press). For example, Elizabeth “The Sid” Siddall worked at a dressmaker’s and at a millinery shop, Fanny Cornforth (real name Sarah Cox), was a house servant, while Annie Miller was working at the Cross Keys pub when Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt spotted her.