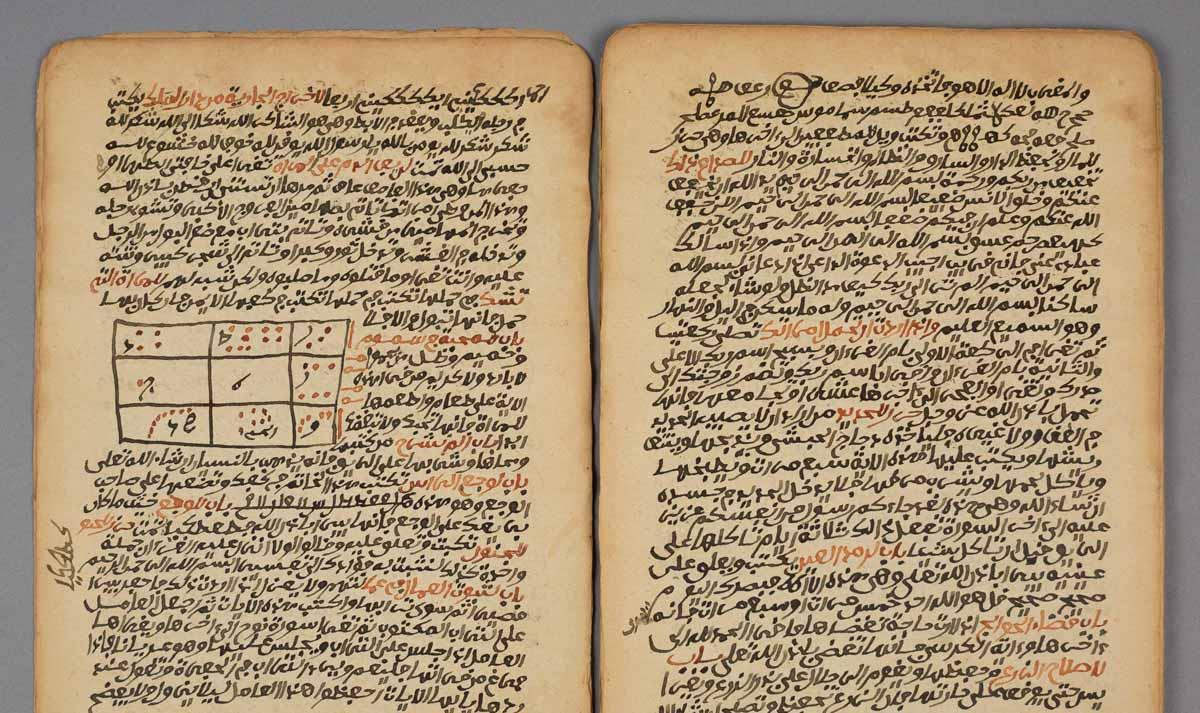

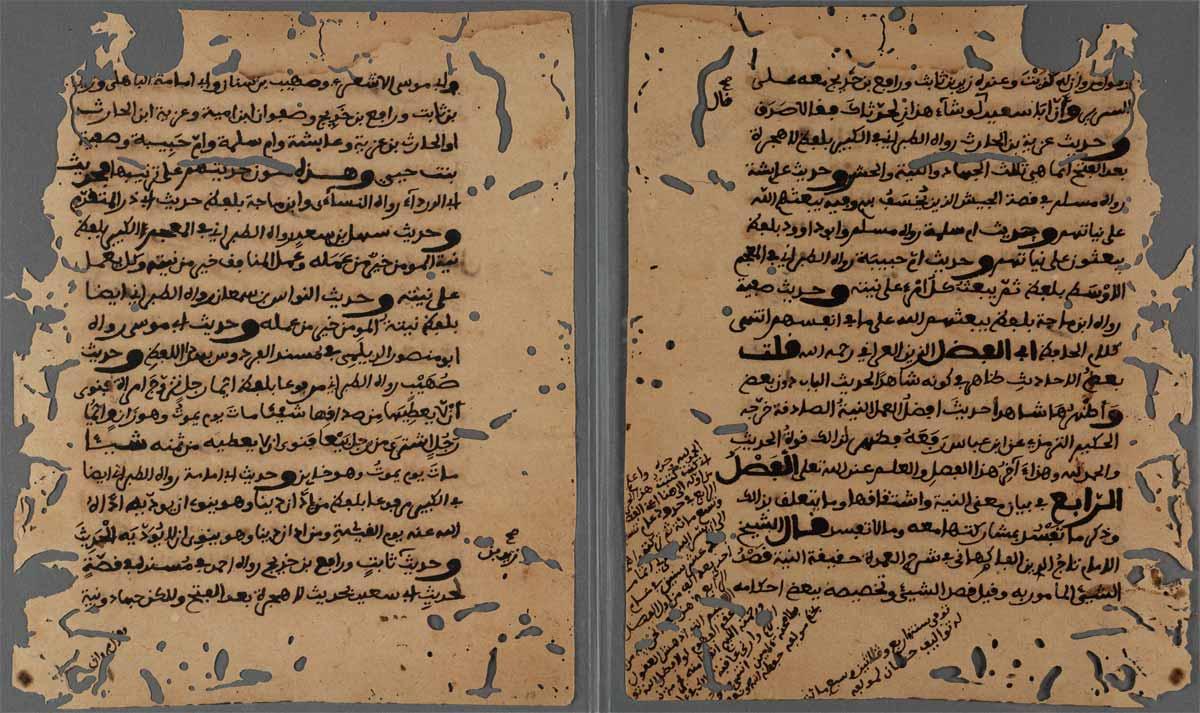

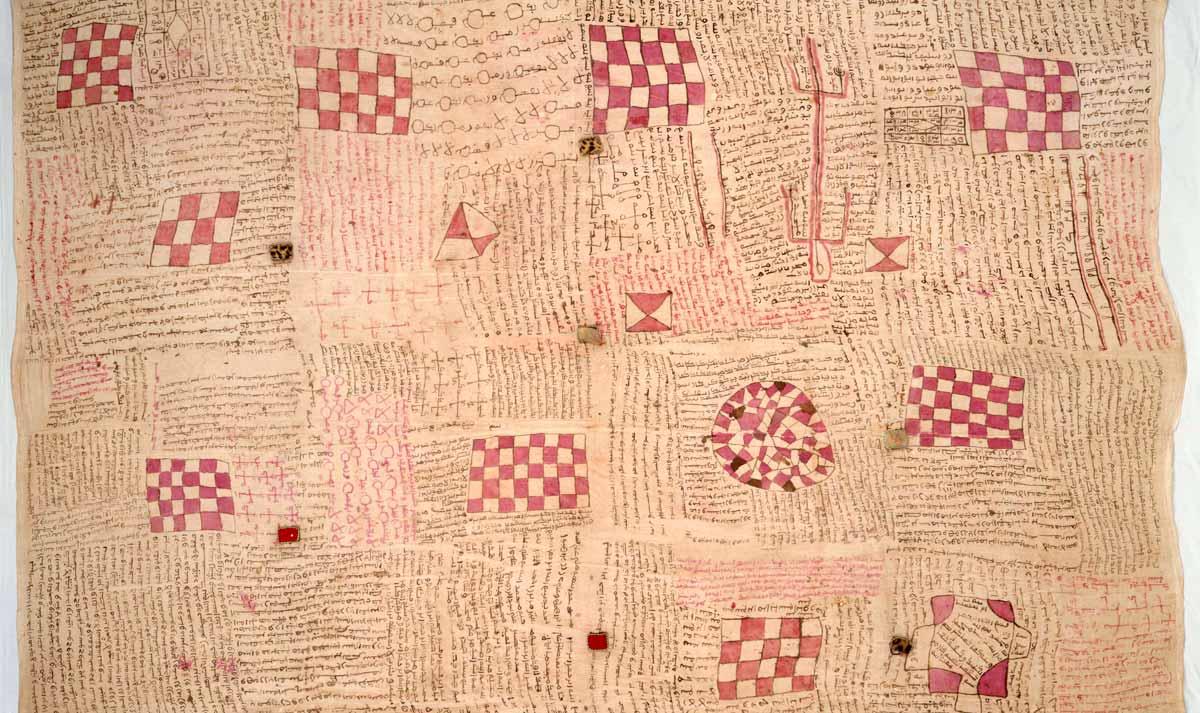

The Block Museum partnered with institutions in Mali, Morocco, and Nigeria to arrange rare loans of African material. “It would be unusual to do that with a single African country, much less three,” Berzock said. “But it was important to work with the source countries and join with them in spreading knowledge about their collections and support their efforts to protect and preserve their cultural patrimony.”

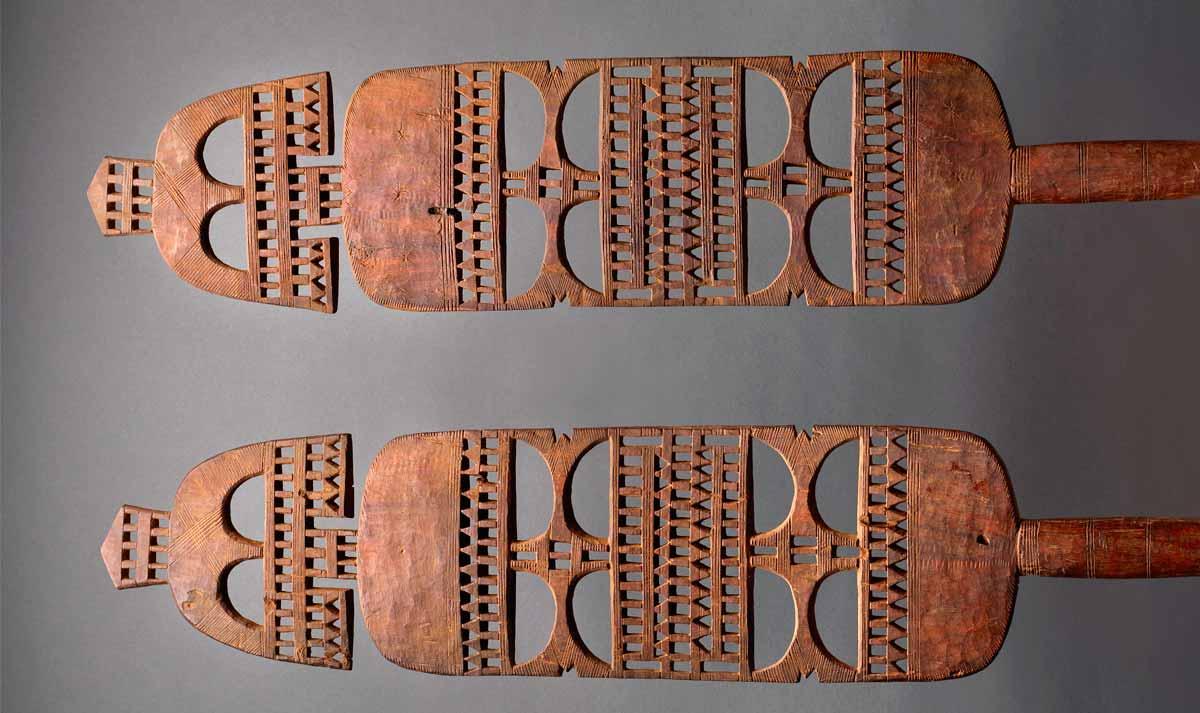

The curator, well aware that viewers might find a fragmentary collection challenging to interpret, introduced other objects to invite people to imagine what these slivers once were. The Chinese porcelain piece, for instance, was accompanied by a similar, fully intact bowl, also from the Song Dynasty. A large, twentieth-century shield from Niger, embellished with copper disks, is one example of how pieces of copper-alloy fittings made in the Western Sudan might have been used.

While gold once flowed through the Sahara, there are few examples of surviving objects of worked gold from the region. As historian Sarah M. Guérin explains in the exhibition catalog, this is largely due to gold’s fungibility and the violence of colonization. One example dates to 1890, when French colonizers invaded an empire in Mali and melted its vast majority of gold jewelry down for bullion. Other coins made of West African gold made their way to Florence and Venice, where they were hammered into gold foil. Artisans then used these thin sheets to embellish panel paintings and frescoes, giving their work a glistening effect when viewed by candlelight.

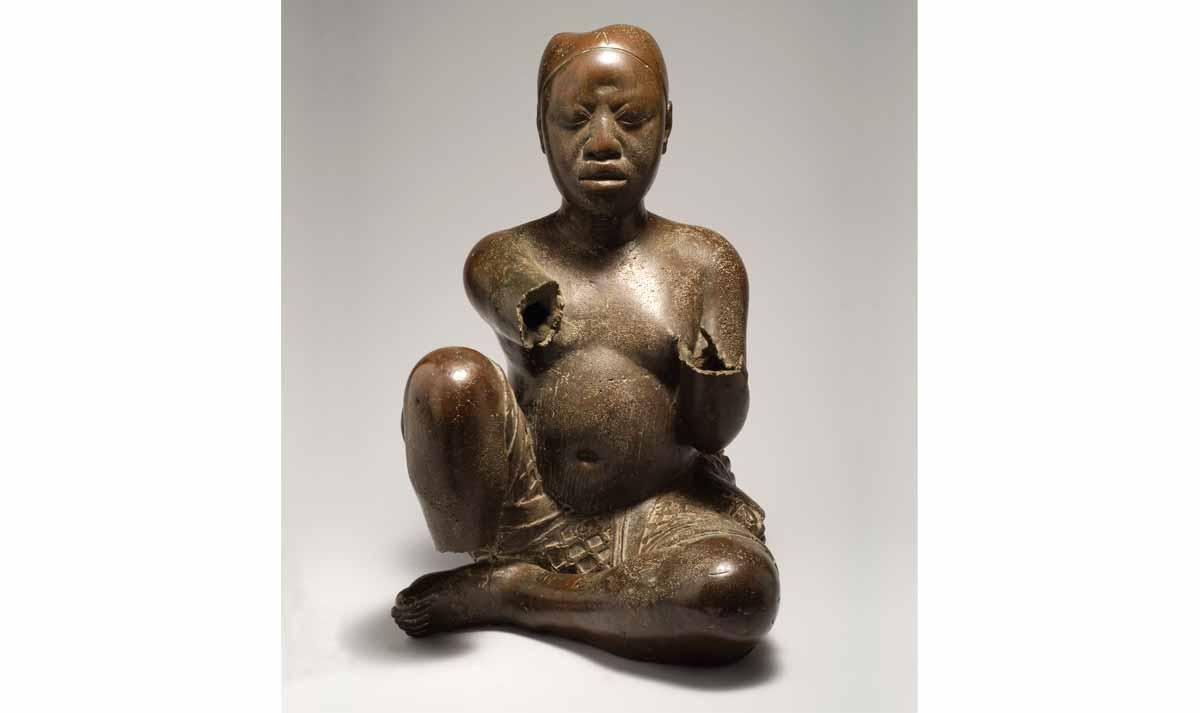

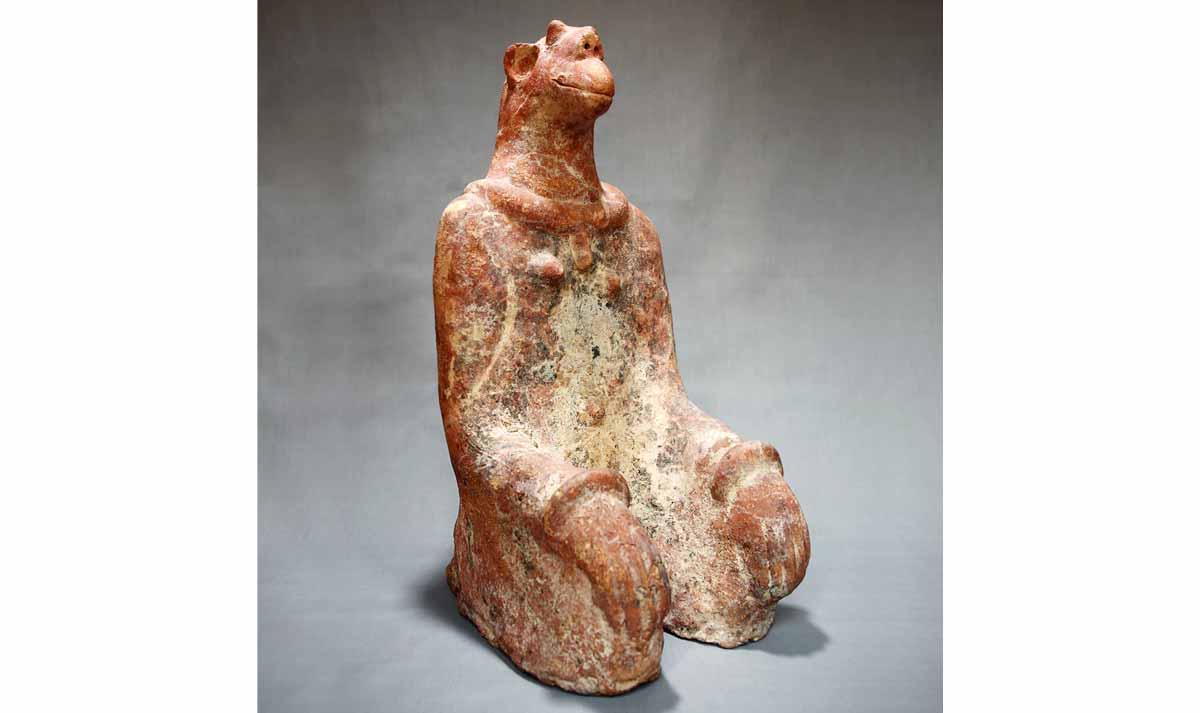

In addition to gold, Europeans also demanded the tragic commodity of ivory from Africa, particularly during the Gothic period. The vast majority of delicate diptychs, caskets, book covers, and other personal objects from this period were made from the tusks of African Savannah elephants, as they were large enough to accommodate intricate figural carvings. The precious material was shipped across the Sahara in caravans along with gold and other goods.

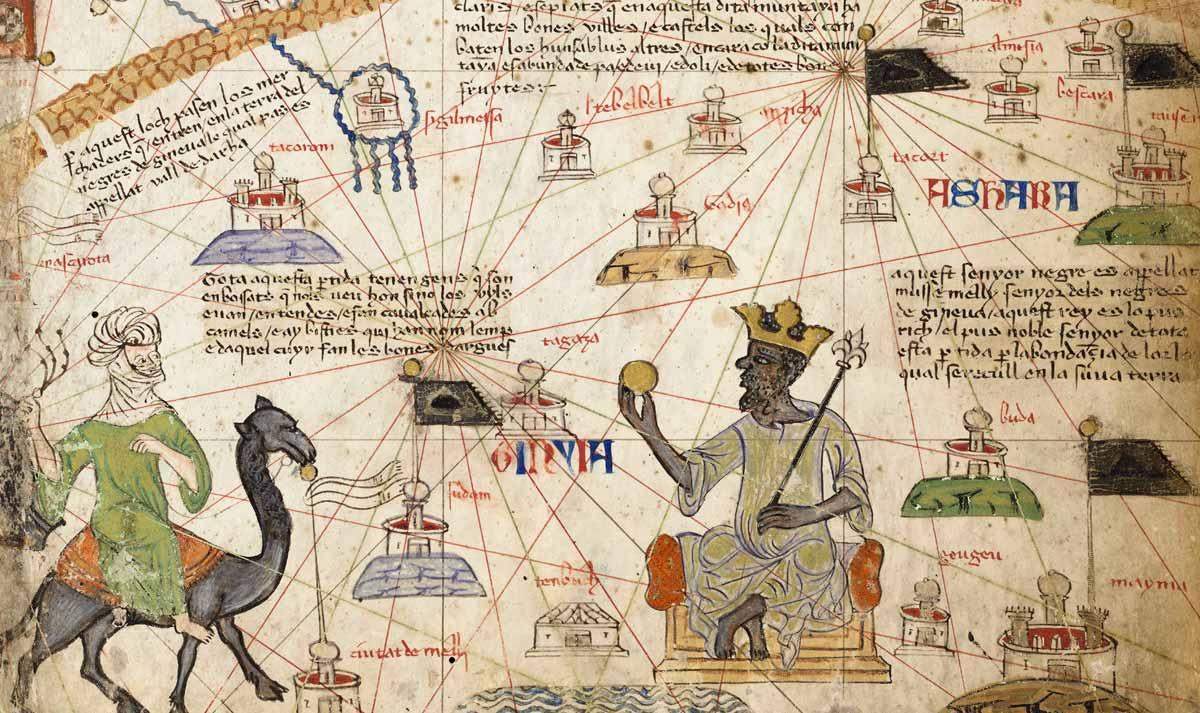

Walk through a major collection of medieval art such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s today, and many of these creamy-white works will gleam from behind display cases, testaments to the skills of European artisans. Yet, any influence Africa had on this major art movement is essentially silent in institutions. Caravans of Gold urged us to think of the medieval world as not just filled with knights and horses in armor but also of veiled nomads and their camels, burdened with riches.