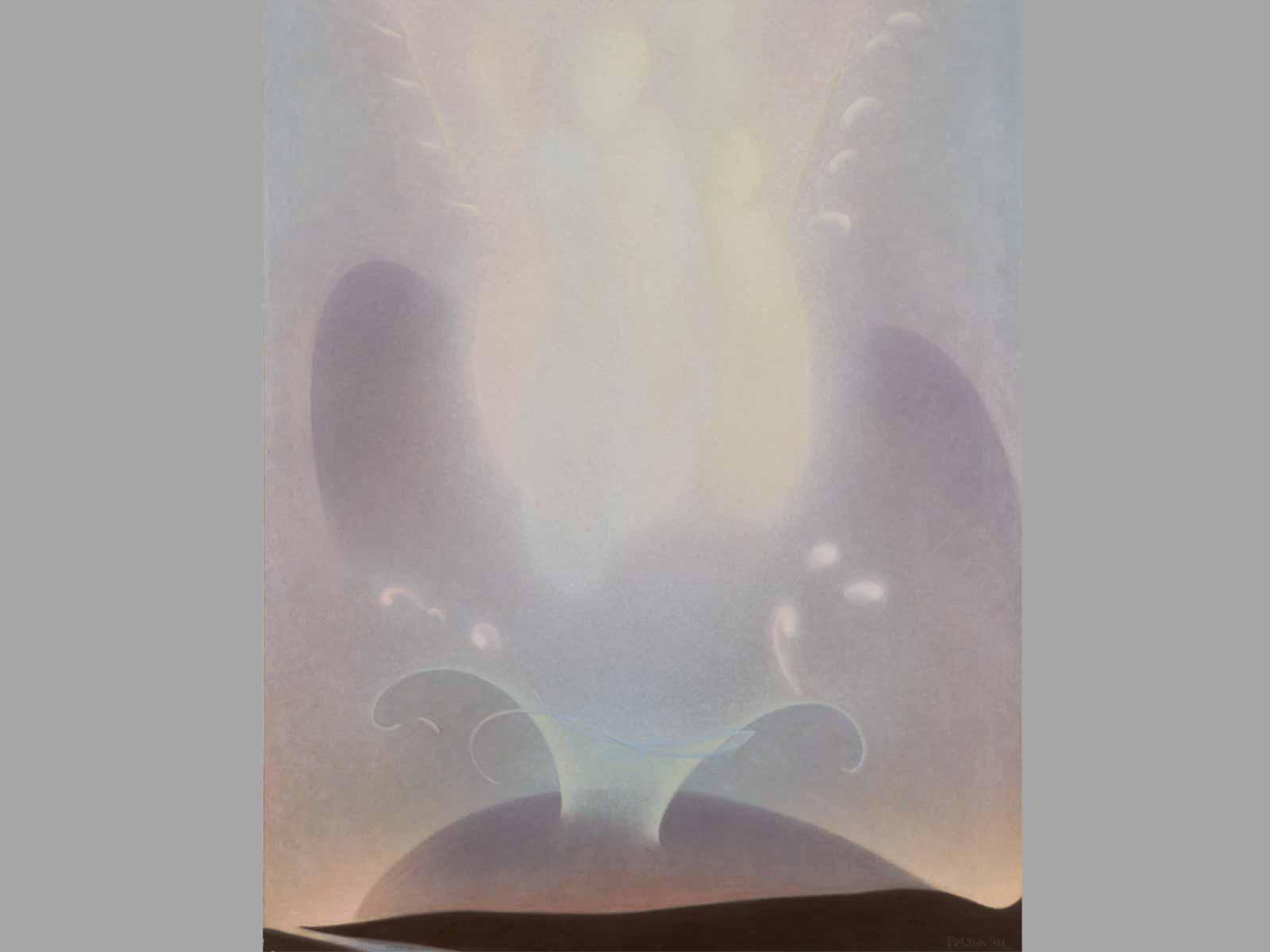

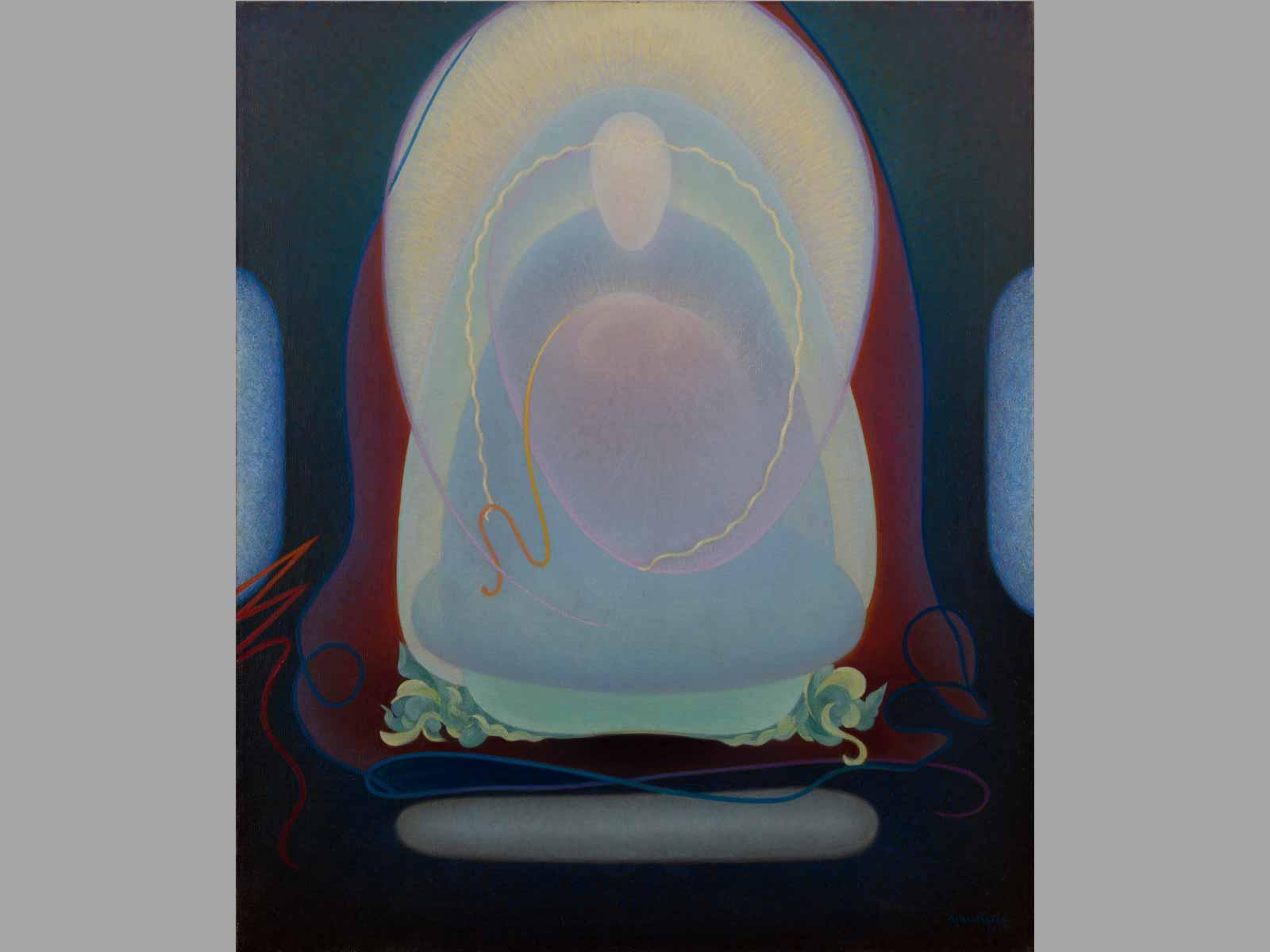

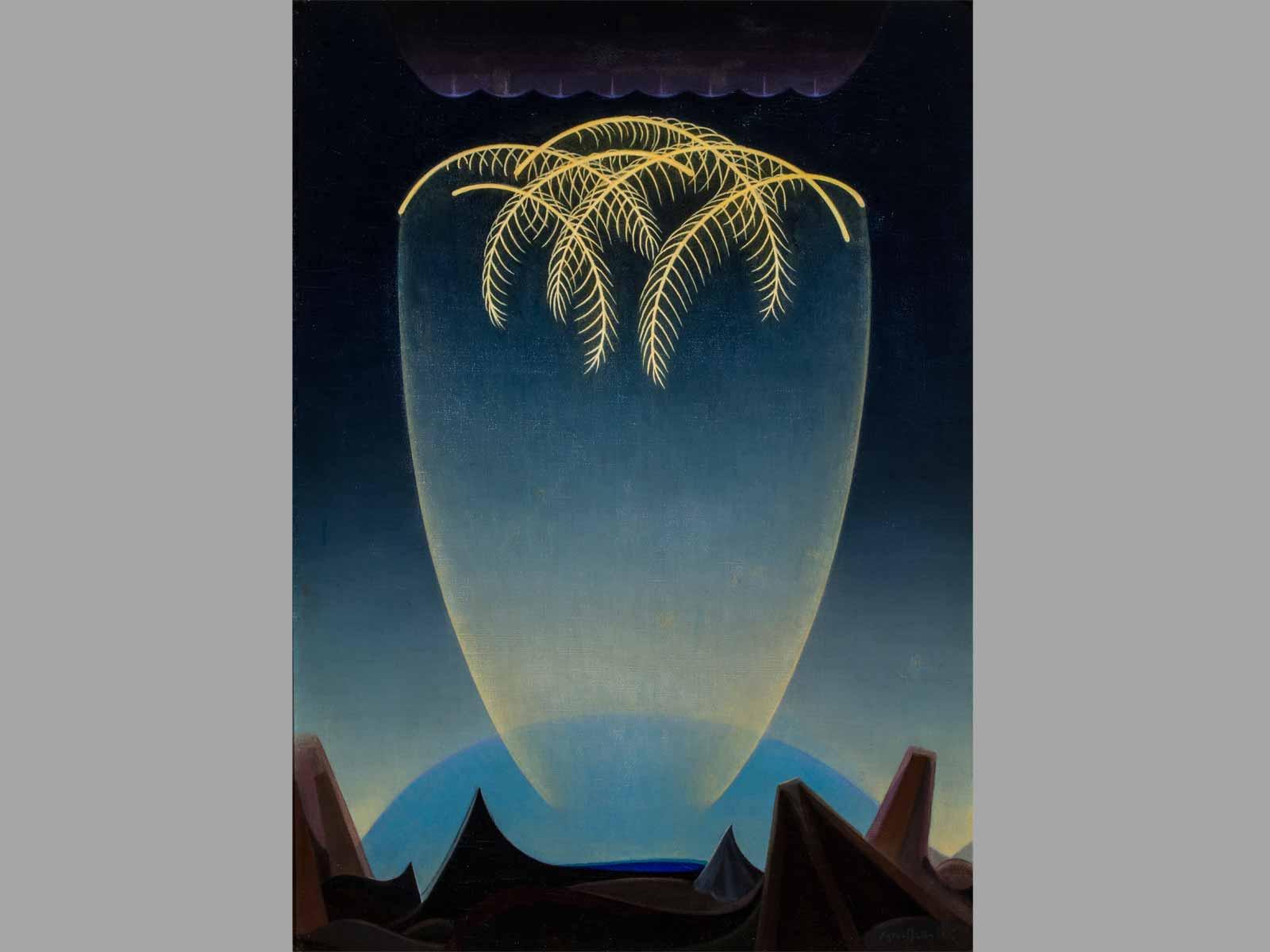

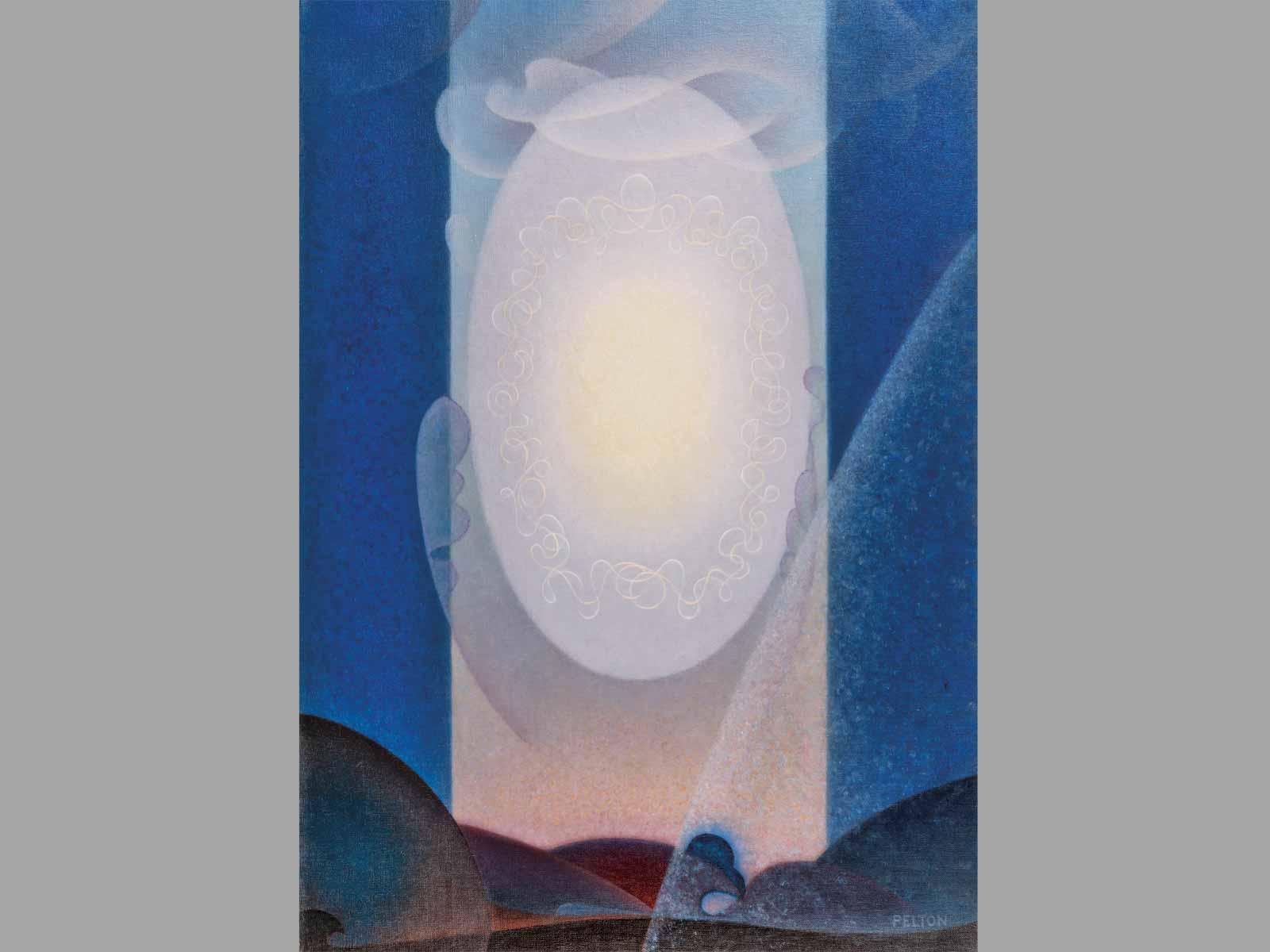

Few outside of Cathedral City, California, noticed when Agnes Pelton died in 1961. Although her close community of friends and neighbors mourned the artist who had painted compelling works that reflected her intensive studies of esoteric beliefs, the art world had largely ignored her visionary compositions. Many who did remember her work were only familiar with Pelton’s more conventional desert landscapes that she painted to support herself.

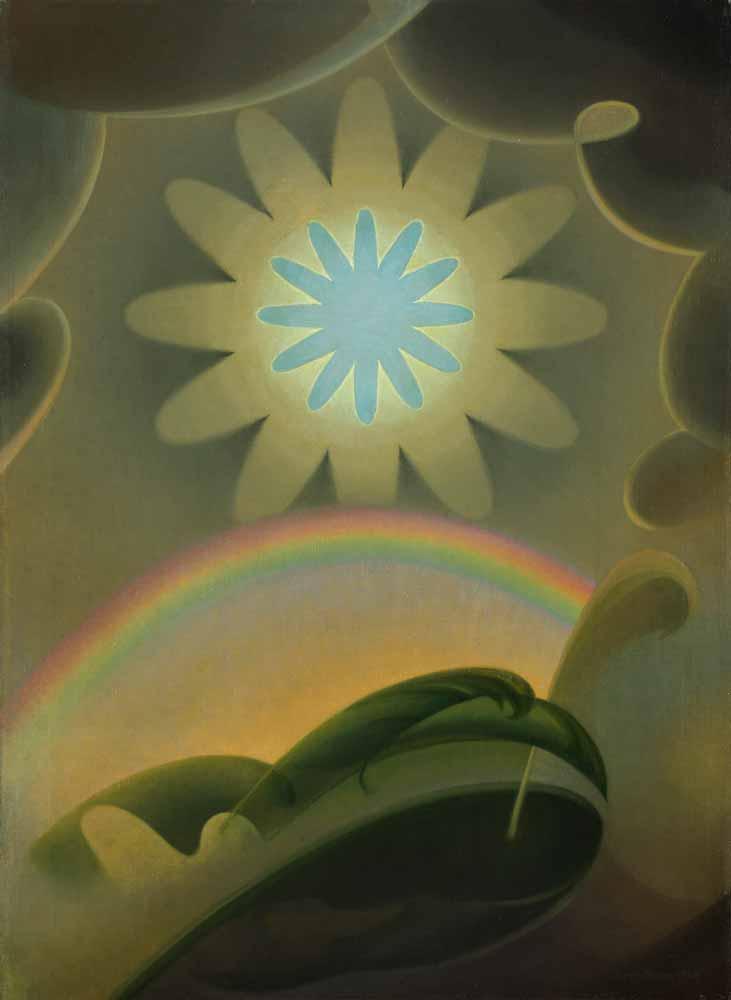

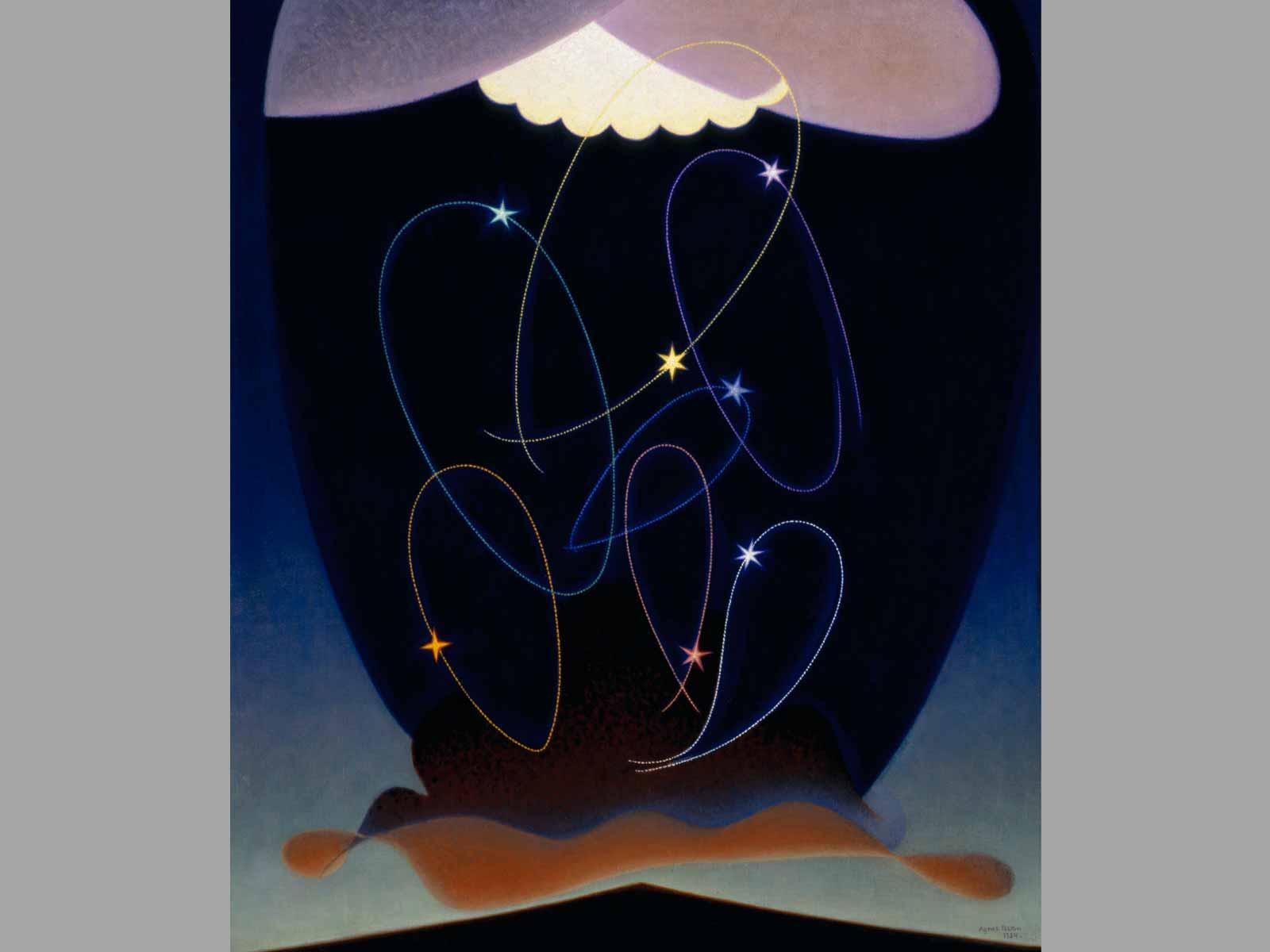

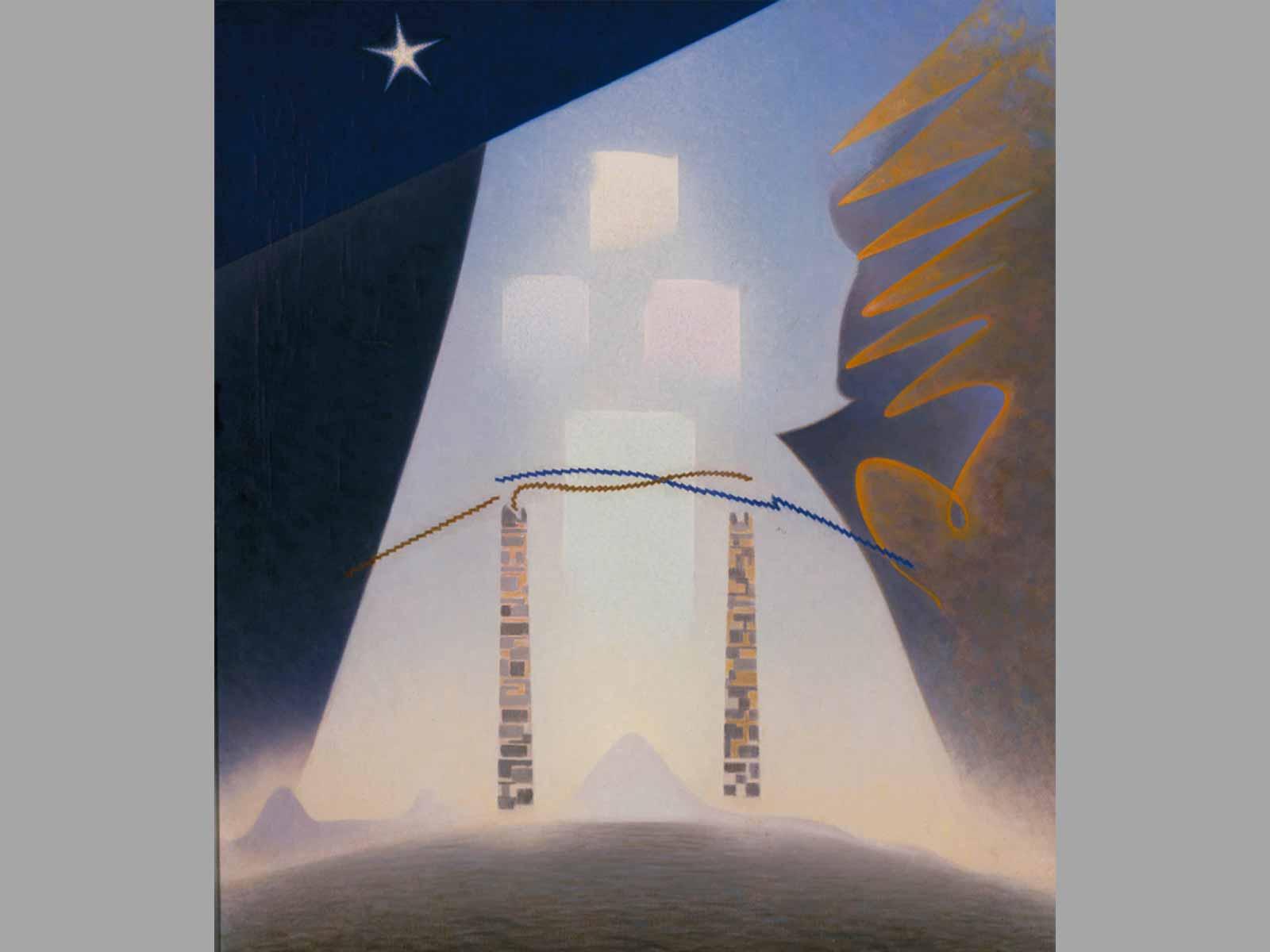

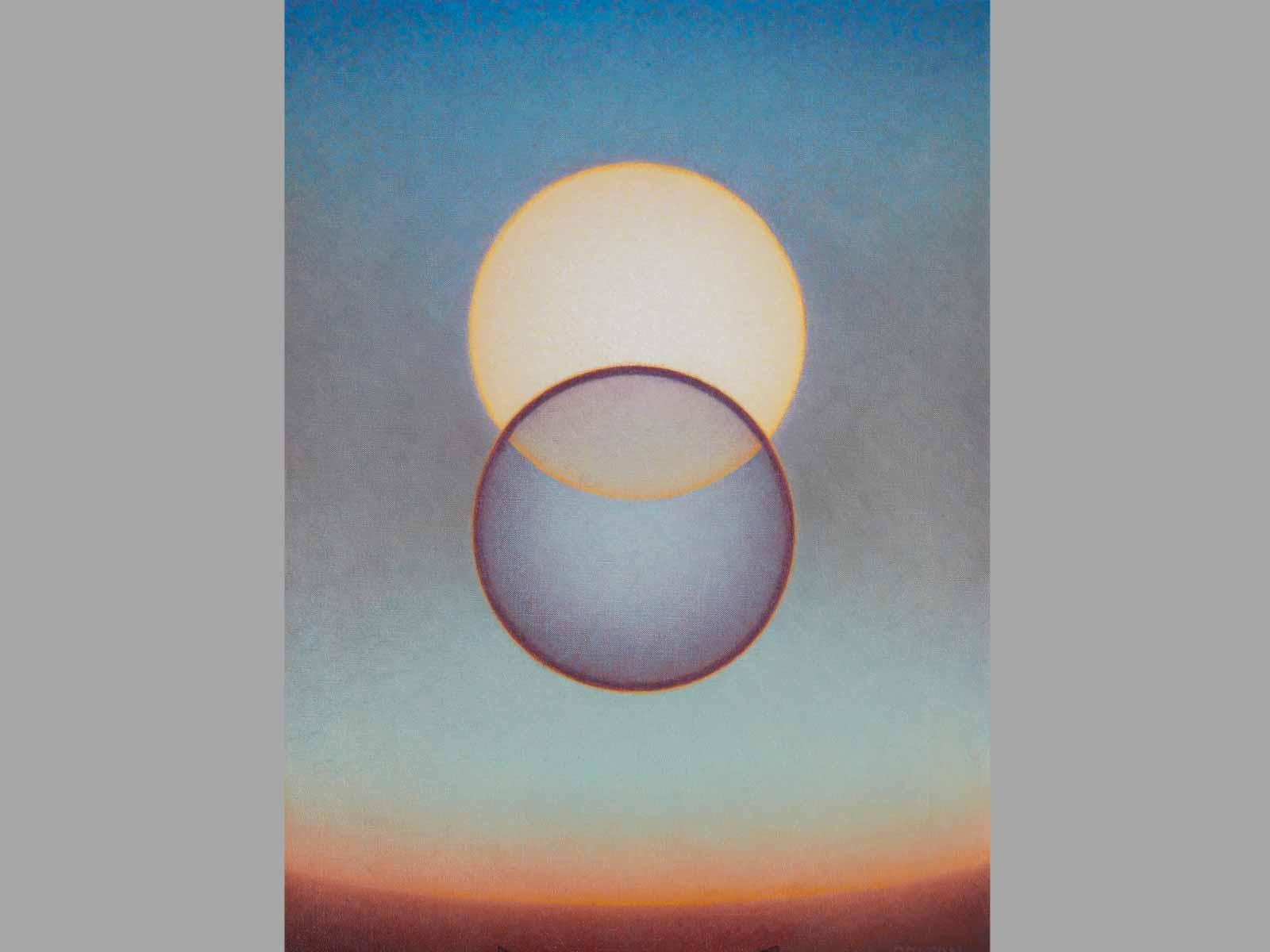

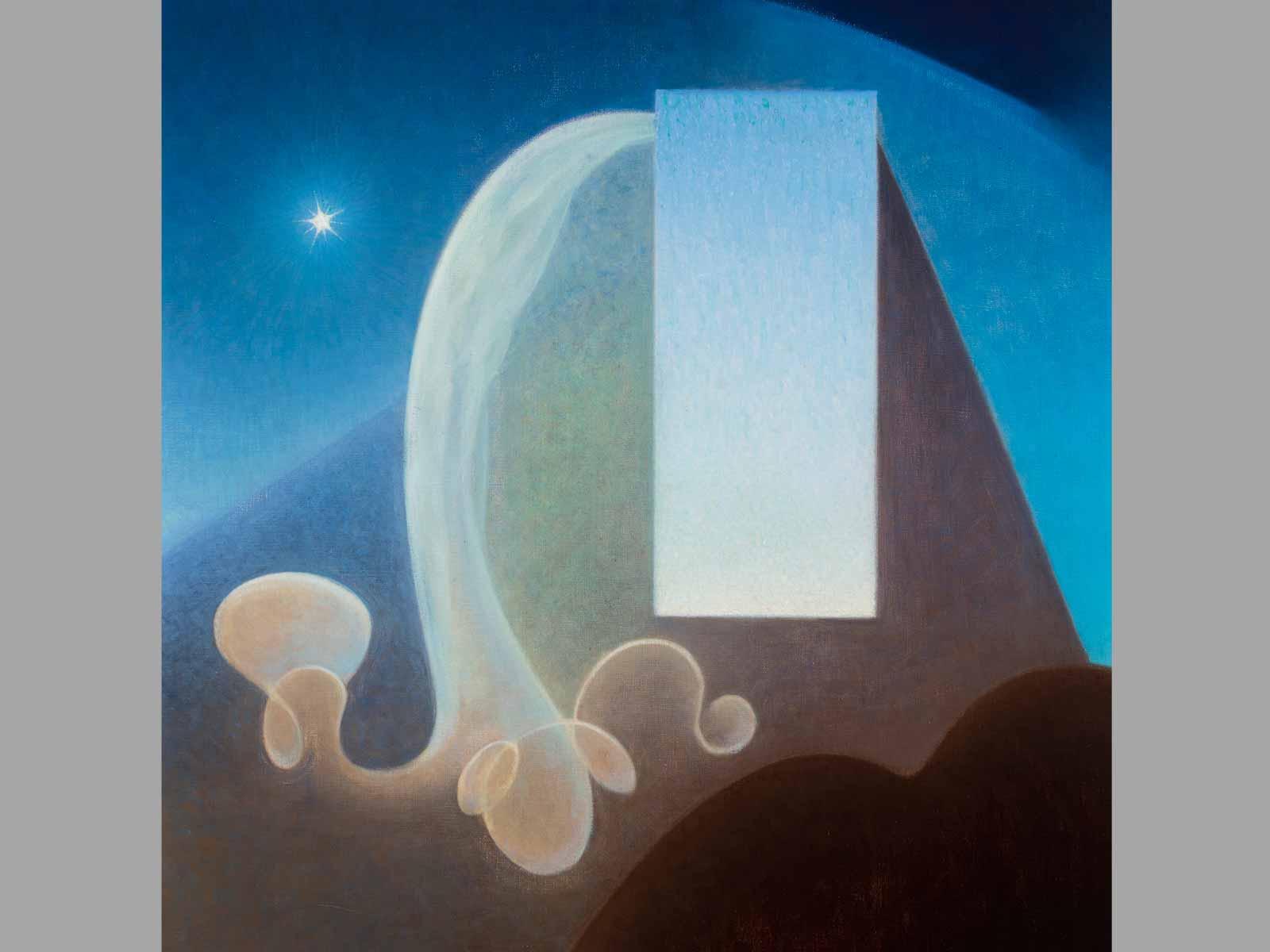

Now Pelton’s abstractions are finally getting the mainstream acclaim they lacked during her lifetime. Agnes Pelton: Desert Transcendentalist, the first survey on her work in over two decades, debuted at the Phoenix Art Museum in 2019 before traveling to the New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe. The show is now on view at New York’s recently reopened Whitney Museum of American Art, after closings due to COVID-19 forced a delay. The exhibition features about forty of her luminous, enigmatic paintings created between 1917 and 1961.

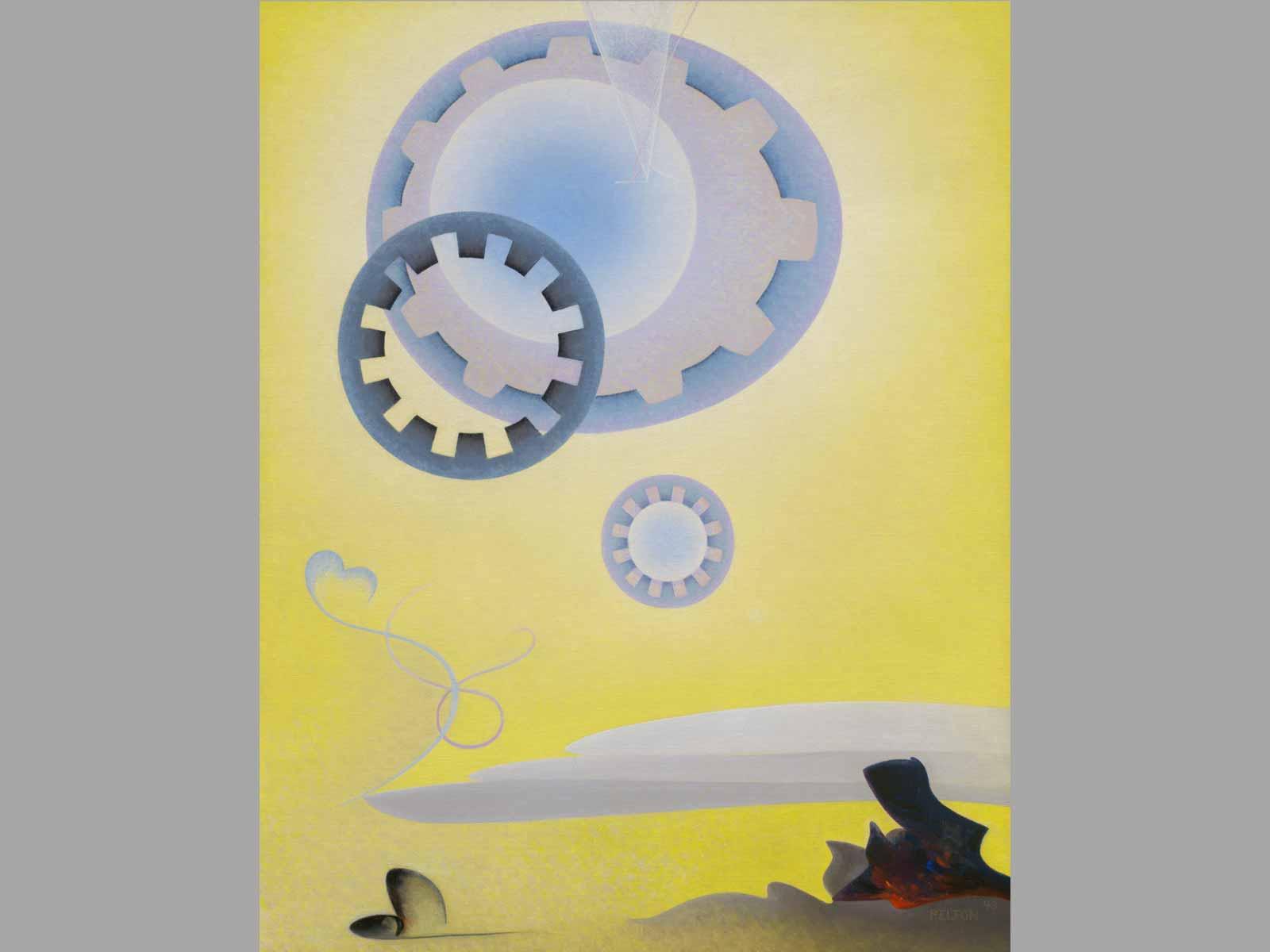

Gilbert Vicario, the Selig Family Chief Curator at the Phoenix Art Museum, was himself unfamiliar with Pelton before his 2015 arrival at the institution. “Like a lot of curators, I had never heard of her,” Vicario said. “Then I found out that the museum I came from—the Des Moines Art Center—had had one of her pieces in their collection the whole time, and I didn’t discover her during those six years that I was in Des Moines. But subsequently, I came to realize that Pelton is really an artist that more artists know about than curators.”