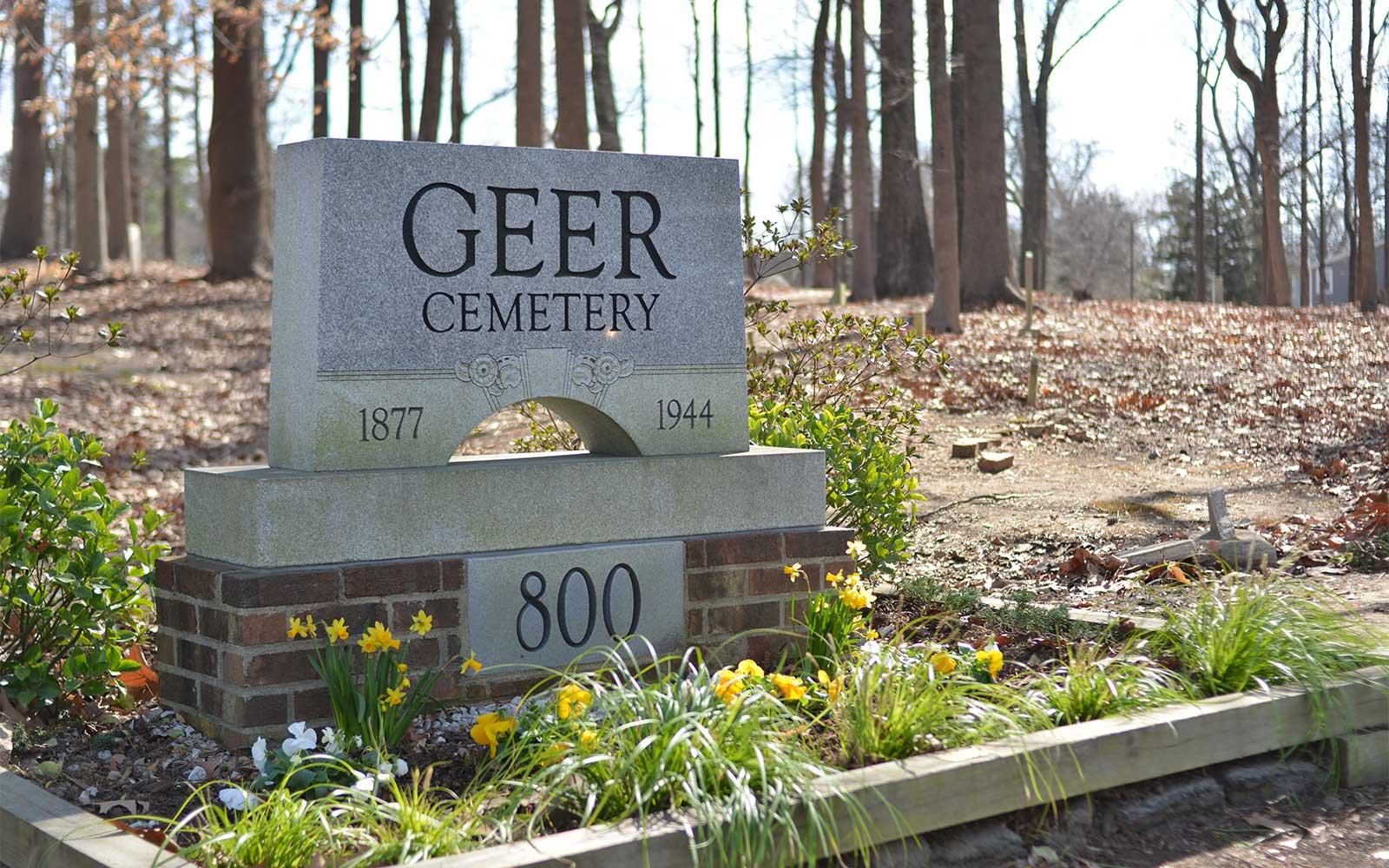

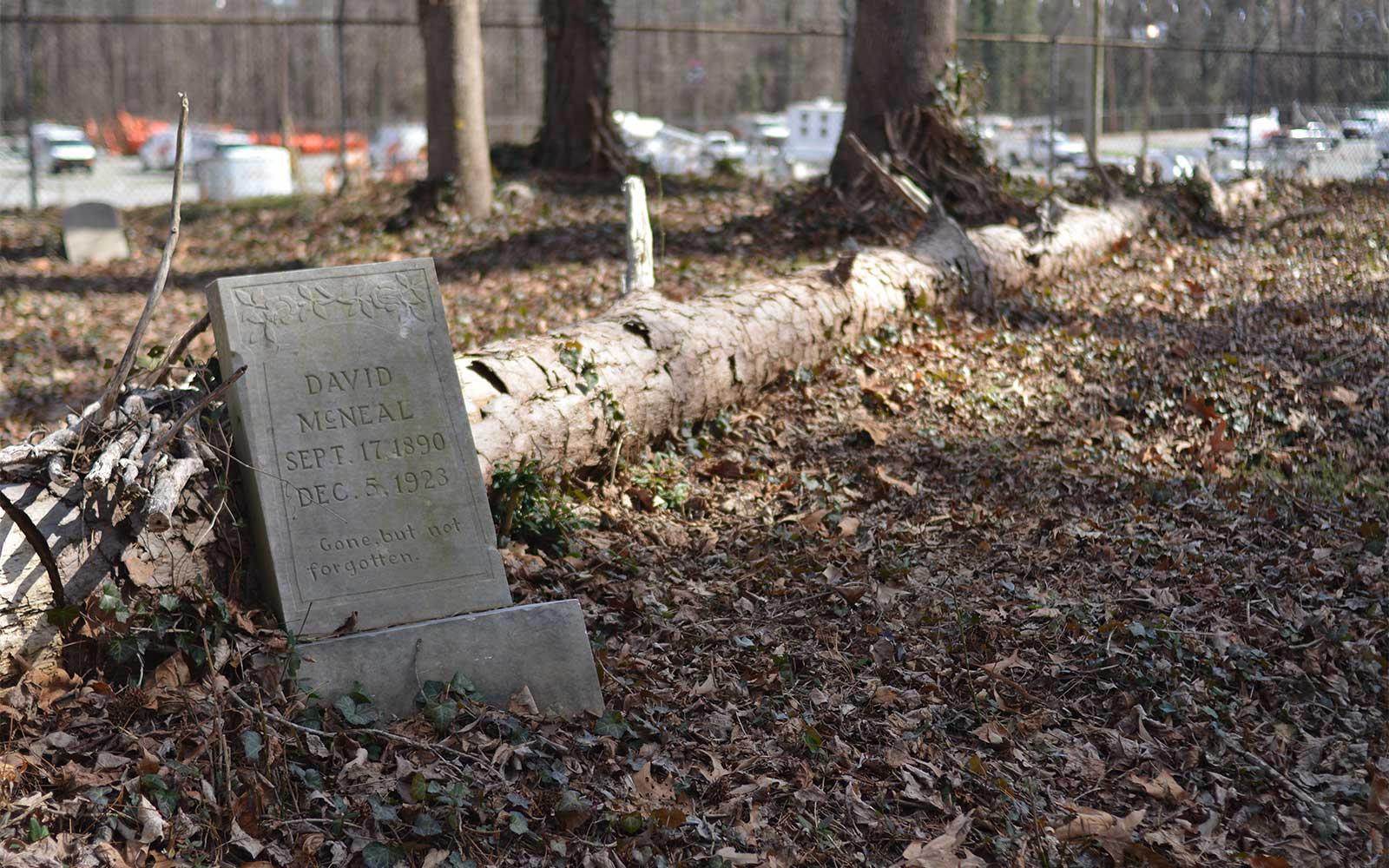

Should one find themselves at the corner of Camden Avenue and Colonial Street in Durham, North Carolina they will find a block of property, quiet and unassuming, canopied under a hundred years’ worth of tree growth. A dirt and pebble path trails through a small cemetery, where stone and cement grave markers intermittently dot the landscape. An intrepid visitor could count the headstones and find them to number around 200. Yet these markers are only the tip of a much larger iceberg, one that includes more than 1,500 burials.

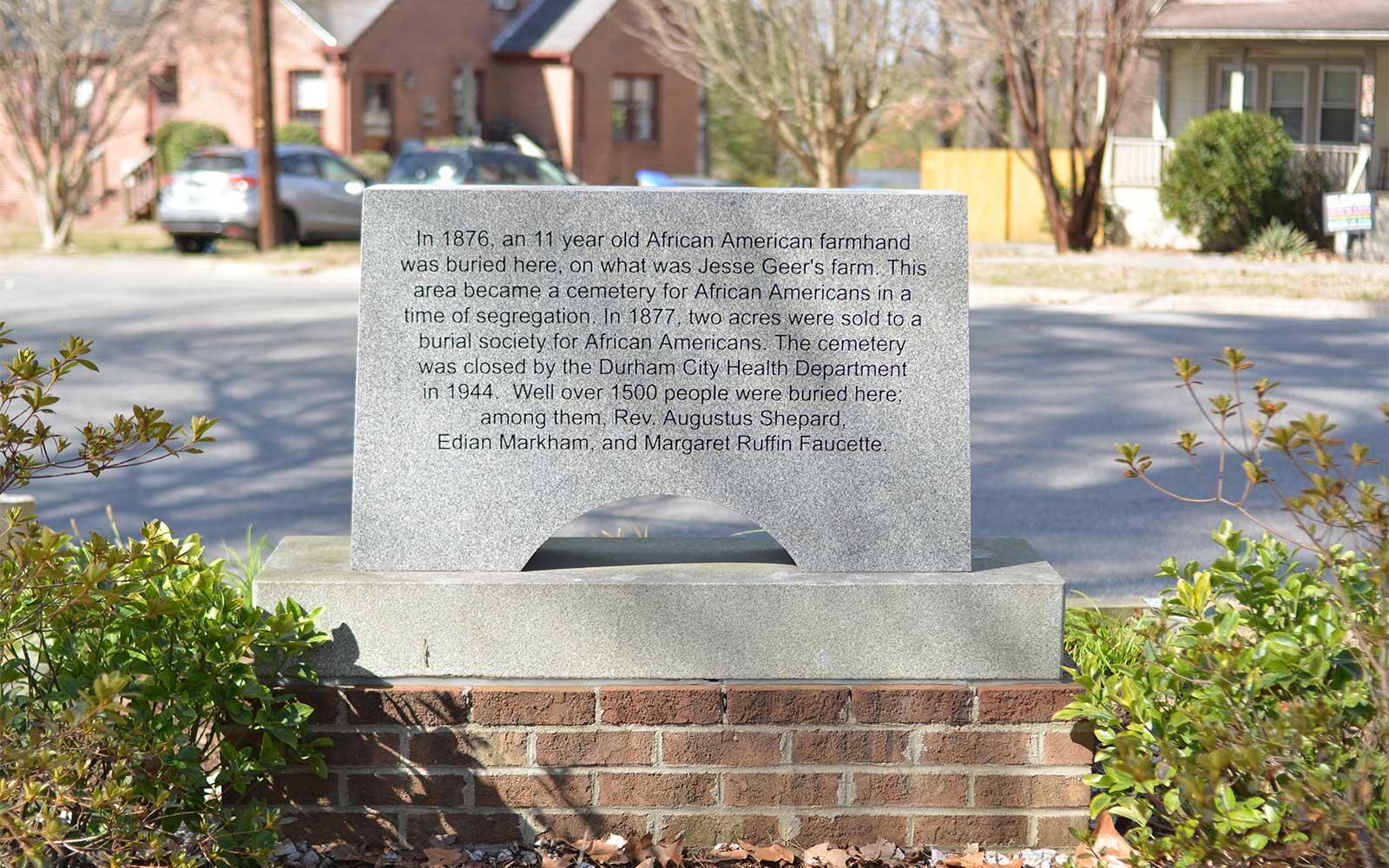

After emancipation, Durham’s Black community was faced with the question of where to bury and honor their dead as cemeteries were still under laws of segregation. A group of three freedmen sought a solution and purchased a plot of land in 1877 for just such a purpose.

For forty-seven years, Geer Cemetery operated as Durham’s sole Black cemetery. By 1939, Geer had been deemed overcrowded and was closed, though one last burial took place in 1944. Between then and now, Geer has miraculously managed to evade complete destruction, but the damage of neglect and outright abuse is starkly apparent with just a glance.

Overrun by destructive tree and ivy growth, vandalism, and developments that have boxed the cemetery in on every side with roads, houses, and telephone company parking lots, Geer is a far cry from what most people would assume a cemetery should be and look like—a problem endemic to countless Black cemeteries. In fact, up until a few years ago, the property was so densely overgrown that it wasn’t even recognizable as a burial place.

In 2020, the Friends of Geer Cemetery—a community volunteer group—arranged for the city of Durham to do some basic maintenance and support of the space such as clearing debris and the removal of overly zealous ivy. Despite these improvements, much of the cemetery remains covered by dense undergrowth, not to mention the annual accrual of fallen leaves and branches.

The task thus becomes a balancing act: How to pursue progress and maintenance while also paying heed to Geer’s fragile state. “We are very cautious with our work preserving the physical space,” says Friends of Geer President, Deborah Taylor-Gonzalez. “We know that there are artefacts in there that will help us to explain some of the narratives, so one of our initial goals is to have an archaeological survey.”