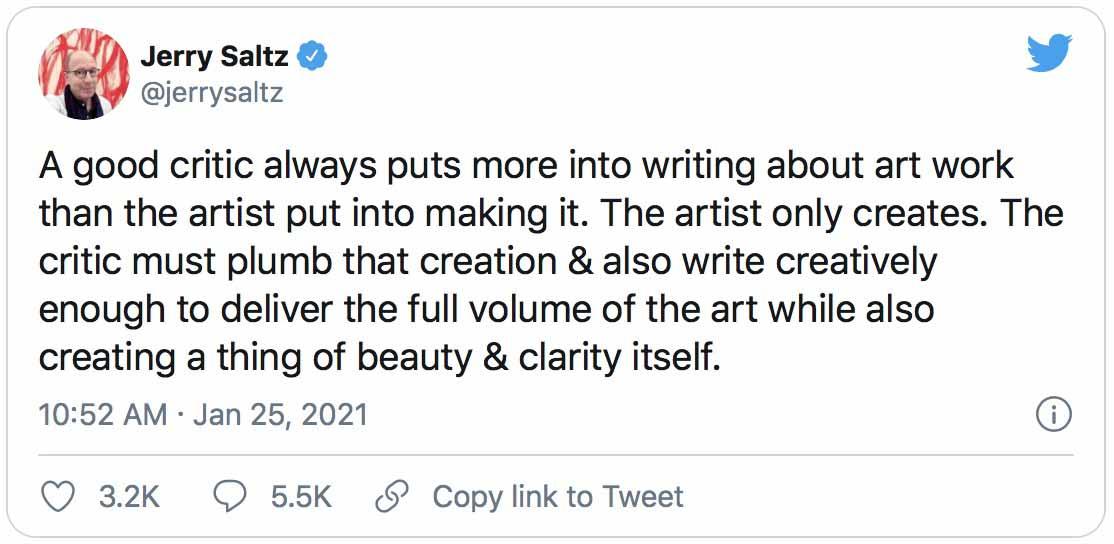

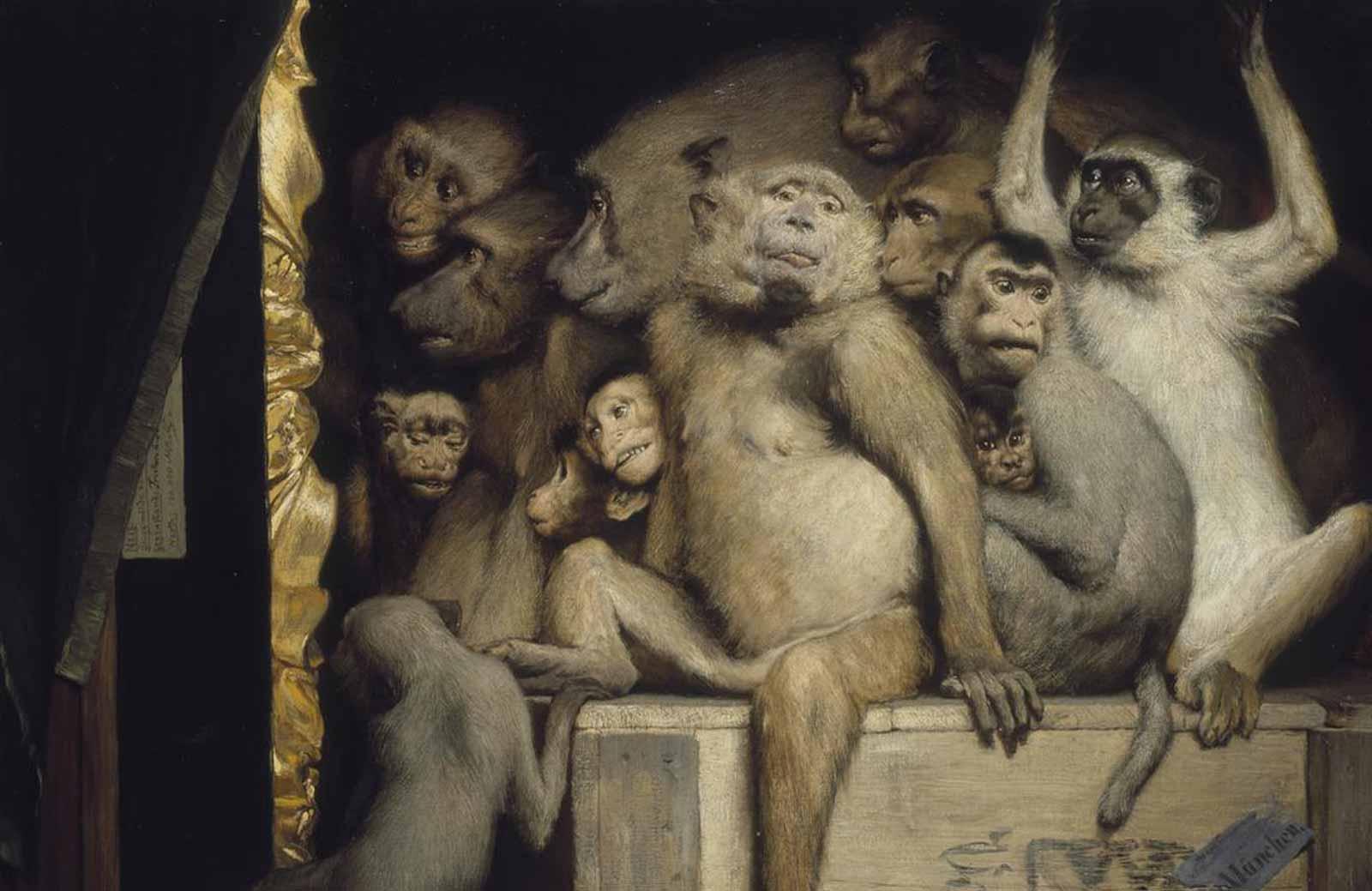

New York art critic and Pulitzer Prize winner Jerry Saltz (1951-) fell in hot water in January after declaring his superior talents via tweet while disparaging the work of artists that provide a reason for his own existence. No stranger to controversy, Saltz tweeted a mea culpa a few days later, but the damage was done and the blowback from colleagues and artists alike was swift. Whether this momentary lapse of judgement does permanent damage to Saltz’s already dicey reputation remains to be seen.

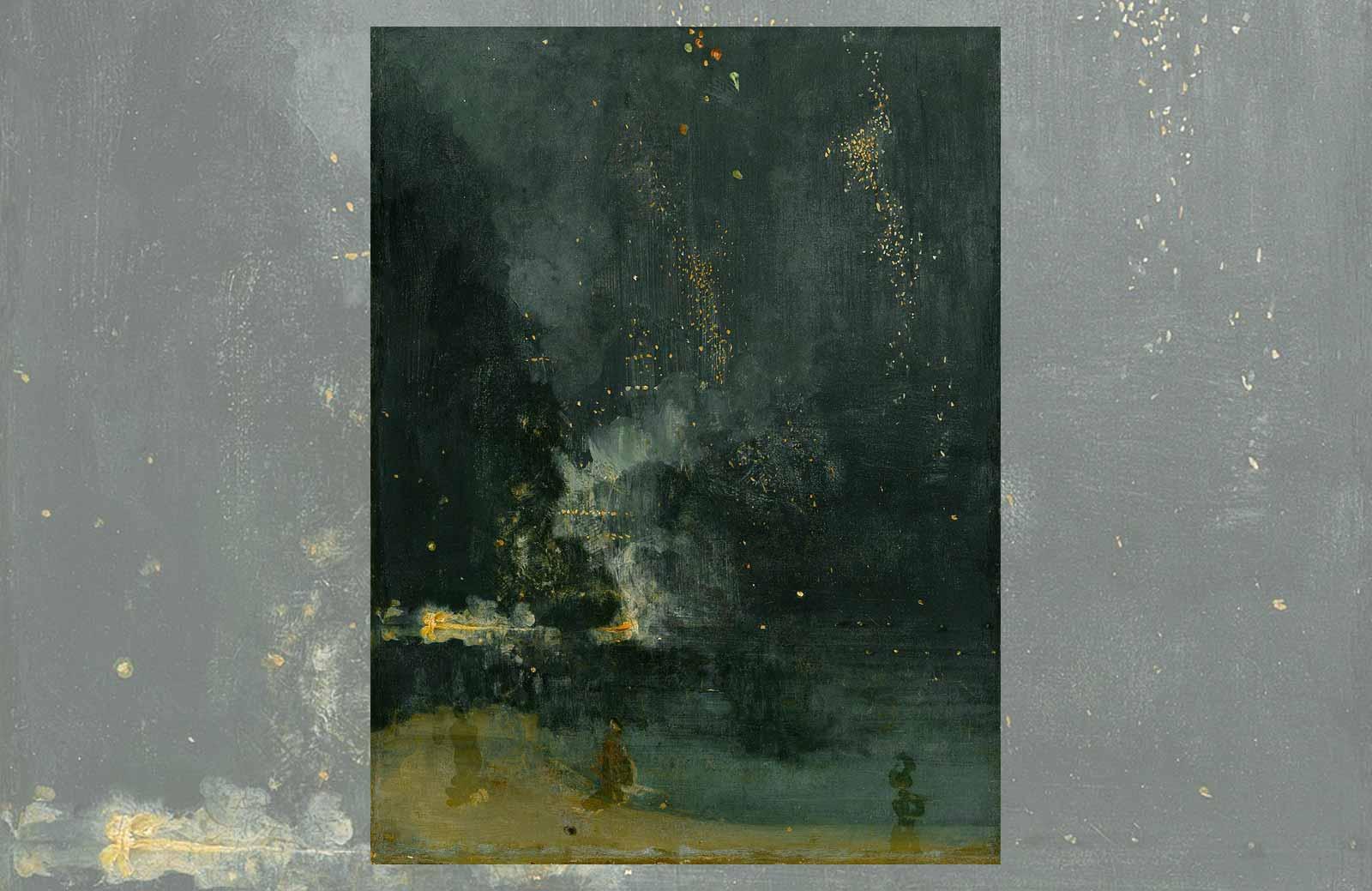

The often-contentious relationship between artists and those who write about art is as old as culture itself. The art critic’s job is to rationalize what is inherently an irrational pursuit. Art historians fall closely on the heels of critics and just as often find themselves tossed on the dustbins of history when the passage of time proves them wrong. The vilification of Impressionism and Van Gogh’s near total lack of recognition by critics in his own time is perhaps the most glaring example of a massive failure in judgement by contemporaneous critics and art historians in the nineteenth century.

In spite of many well-documented failures among critics and art historians, artists, sometimes grudgingly, recognize the need for these interpreters of culture to act as a bridge between the isolation of the artists studio and recognition by the art going public that may translate into dollars and cents in the marketplace.