“We want to be subversive, to transform our audience, to confront them with some disarming statements, backed up by facts—and great visuals—and hopefully convert them.” —The Guerrilla Girls

Artivism: Making a Difference Through Art

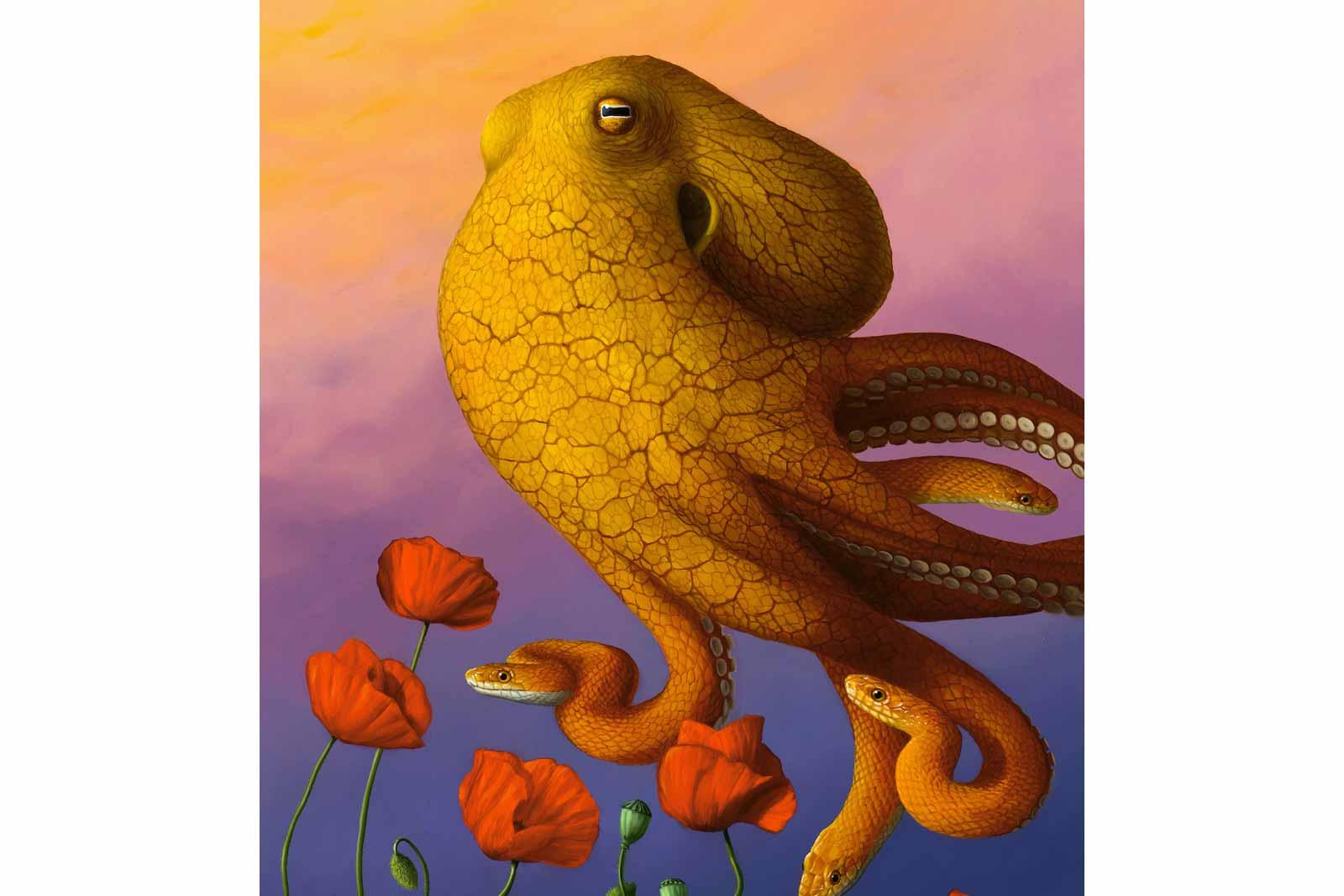

Jon Ching, Cache, 2020. Oil on wood, 24 x 18 inches.

Using art as a means for social change, artivists can change the world

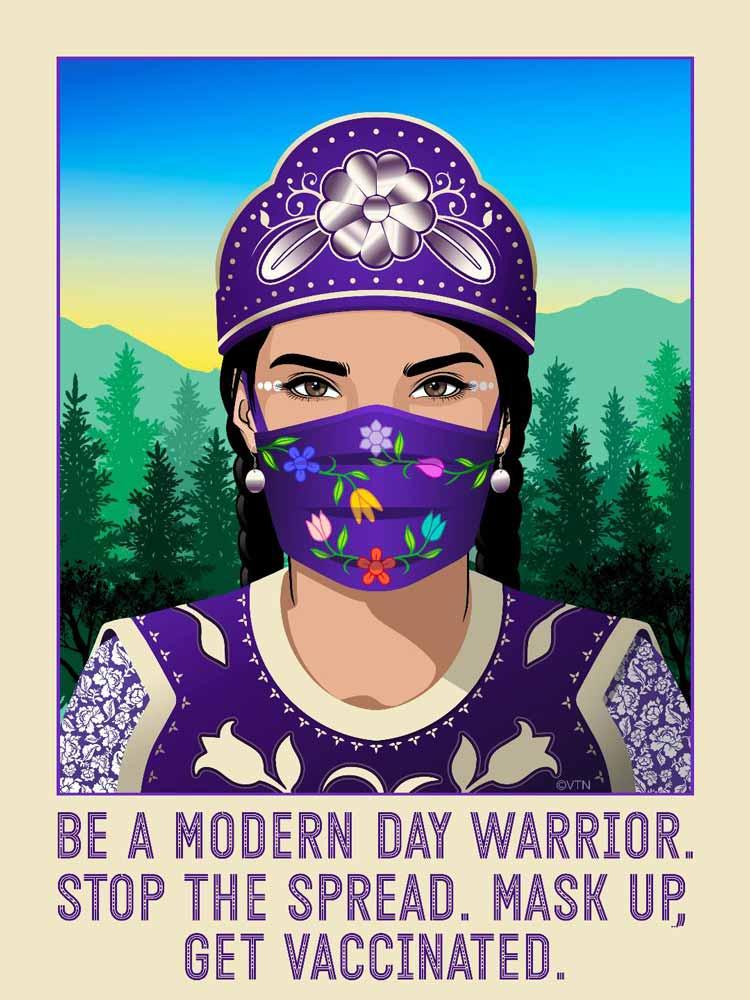

Votan Ik, Woodlands Warrior.

“Propaganda tells you exactly what to think, feel, and do, whereas good artivism should inspire critical thinking and empathy."

Dannie Snyder

Pablo Picasso, speaking of his now world-famous anti-war painting, Guernica, boldly declared: “Painting is not made to decorate apartments. It's an offensive and defensive weapon against the enemy.”

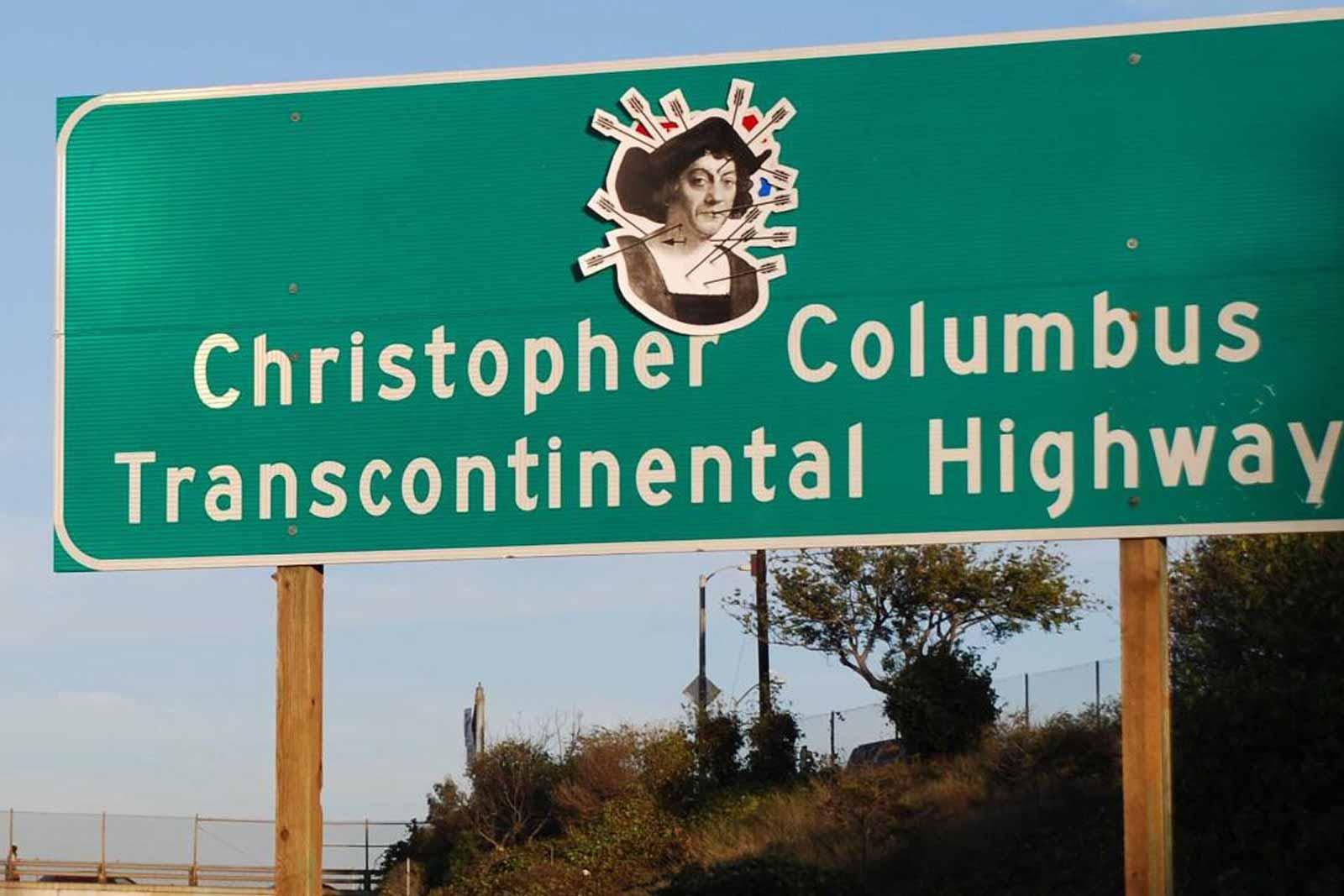

Whether you call it artistic activism or artivism, the compound word keeps gaining traction. The use of creative expression to cultivate awareness and social change spans various disciplines including visual art, poetry, music, film, and theater. To make their points, artivists cleverly employ parody or satire through culture jamming and other forms of subvertising–a portmanteau of subvert and advertising– to change the original meaning of a well-known image or corporate logo. The Guerrilla Girls were making the most of anonymity around a decade before Banksy, first donning gorilla masks in 1985 to point out gender and racial imbalance through humor and facts.

Since co-founding The Center for Artistic Activism in 2009, Steve Lambert and Steve Duncombe have trained and mentored over 1,500 artists and activists around the world. Duncombe is an activist, author, and professor of Media and Culture at New York University. Lambert, an artist and professor of New Media at Purchase College, New York, does not use the term artivism; he feels it implies the need for a new term to describe a long-standing combination.

While artivism is said to have started with the Chicano movement in Los Angeles in the late 1960’s, Lambert and Duncombe investigated further. “We had a hunch that art and activism were a powerful combination…, but when we tried to dig back to the beginning, there was always something that came before,” says Lambert. “When you start looking closely, every successful activist movement involves creativity, culture, and innovation,” Duncombe adds. “What we realized in the end is that *all successful activism is artistic activism*.”

Lambert points out that most activist organizations – and sometimes even artists themselves – seriously underestimate the role artists can play. “They can do so much more than simply help to ‘raise awareness,’ he explains. “Limiting artists to that role doesn’t tap into much more potent ways creativity works within movements.”

Dannie Snyder is an interdisciplinary artivist as well as the co-host of Re-Flect/Calibrate. In this podcast, she focuses on professional artivists and the genealogy of the field. “Since I began my studies in film and theater,” shares Snyder, “I have focused on using art as a means for social change, because I feel like my life is more fulfilling if my art does more than just entertain, when it significantly impacts culture and society.” She is currently focusing her own efforts on several causes including Prison Abolition and Free the Vaccine. “To tackle complex issues like the criminal justice system, we absolutely require creative problem solvers and visionaries….”

When evaluating an effective campaign, Snyder considers how artivists are changing behaviors, pointing out the difference between merely raising awareness through the use of a hashtag versus inspiring measurable responses such as visible, physical actions. Starting with a clear objective, artivists must be willing to ponder creative routes and employ tactics to measure the efficacy of their intentions, she says.

While mass production of an image is certainly one approach, this can lead to a fine line between activist-driven art and propaganda." With propaganda, there is less room for interpretation," Snyder explains. “Propaganda tells you exactly what to think, feel, and do, whereas good artivism should inspire critical thinking and empathy."

Peggy Diggs of Galisteo, NM refers to herself as an art worker concerned with social justice. “I don’t tend to think that any one person can change anyone’s beliefs, much less behavior,” says Diggs. “I think attitudes can be cumulatively nudged towards justice if people are presented with multiple renditions of thinking not like their own.”

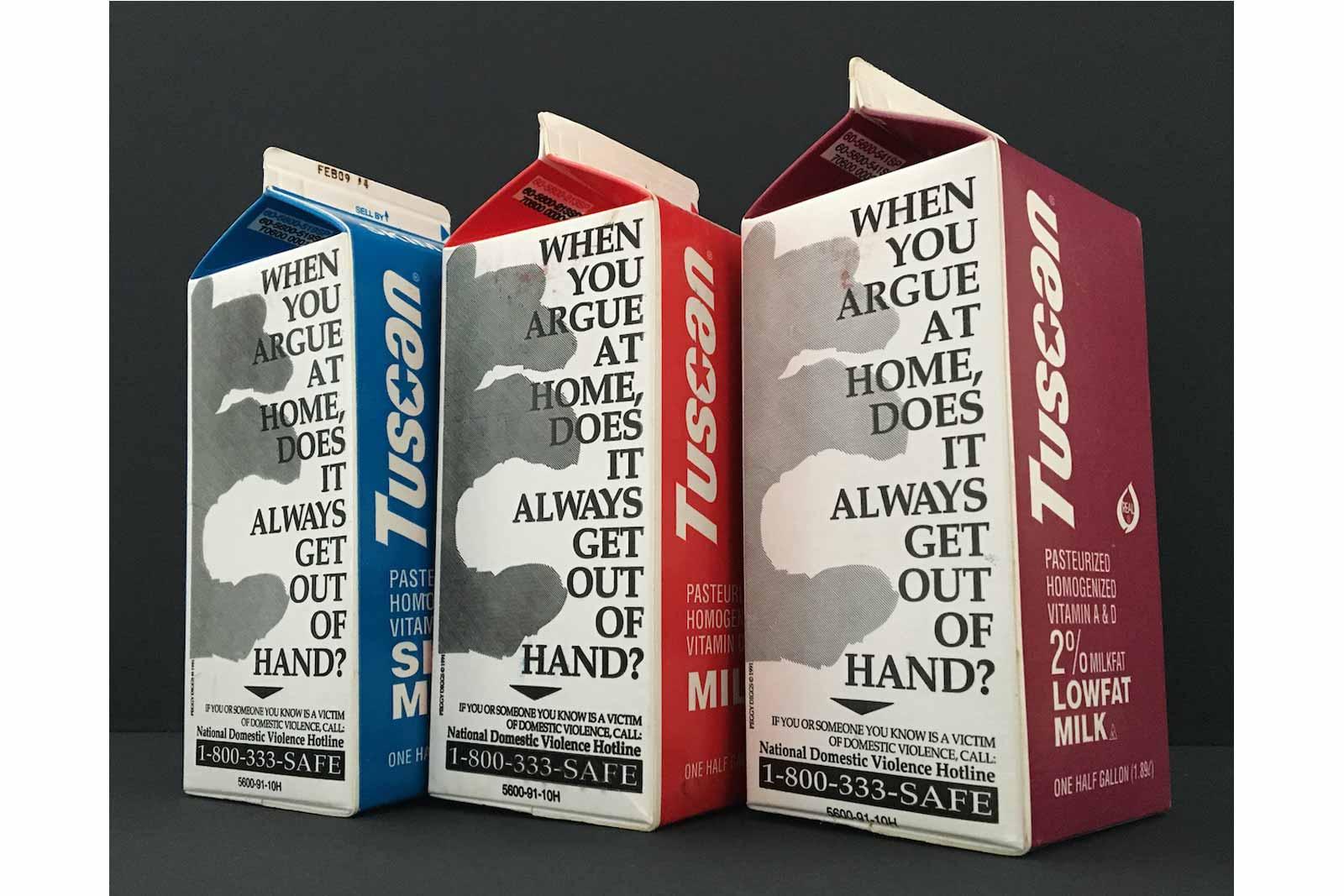

Her first public piece was the Domestic Violence Milk Carton Project in 1992, consisting of 1.5 million milk cartons in four different designs. The artist’s extensive research into the battered women's movement included interviews with two women imprisoned for killing their abusive partners–one of whom suggested a grocery display where others affected by domestic violence could see the work. “The hardest part was finding a dairy that would do it,” shares Diggs.

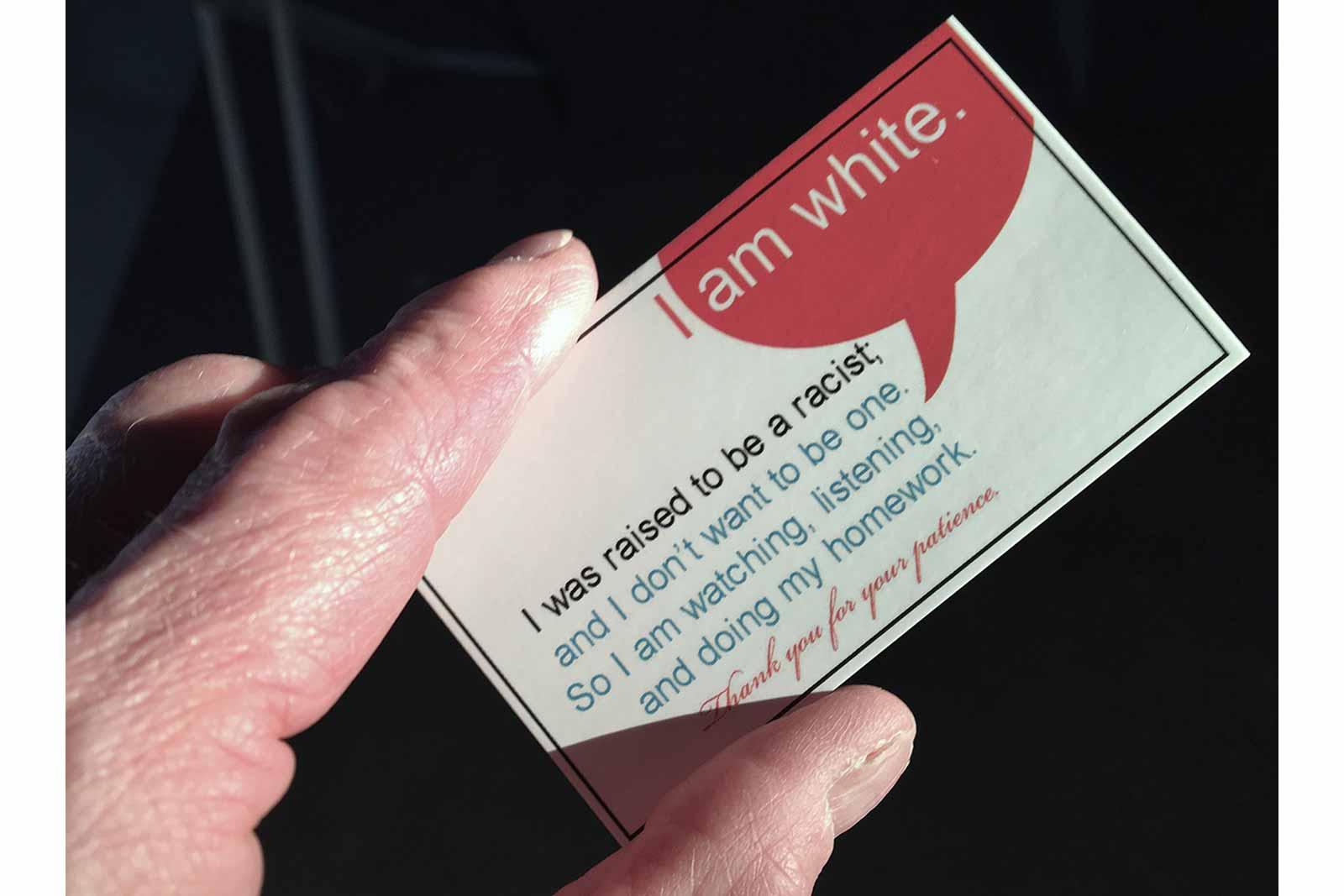

Since around 2007, the artist has been exploring racism, often in the form of distributed multiples including business cards and junk mail. She was prompted by a grim personal discovery: “After my dad’s death that year, I found among his old family papers a receipt for a slave. That did it.”

After interviewing participants about race to create her Being White series, Diggs challenges white viewers to explore their privilege. “I think now my target audience is older White people, folks raised with an unquestioning belief that being White … It’s the unquestioning part that I want to grapple with.”

While Diggs also creates gallery work, she says: “I love public work because what intrigues me is taking very familiar formats—yard signs, paper napkins, billboards—and using them in unexpected ways. So much media flies by us, but I think this approach trips folks up and they are likely to pay attention.”

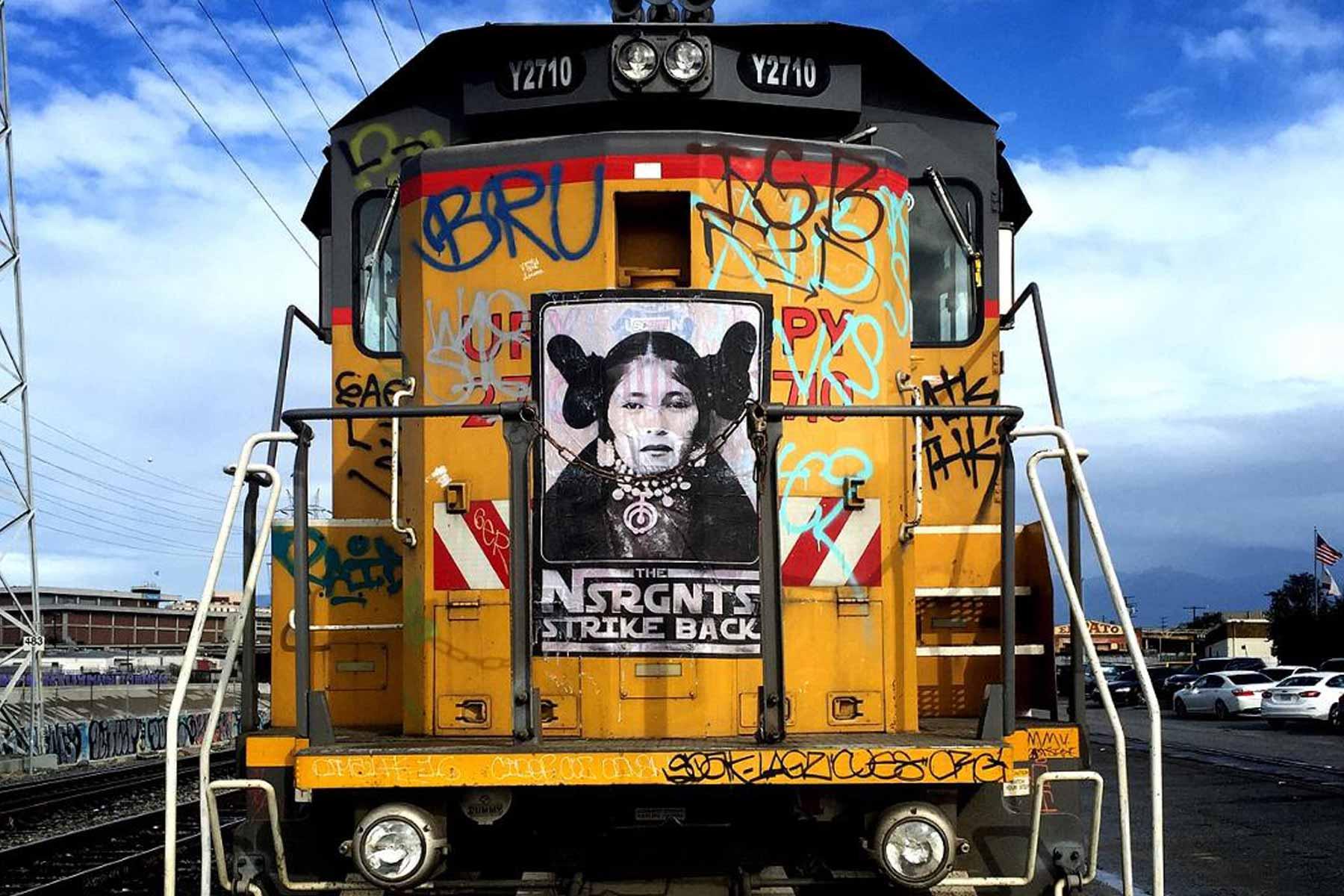

Artivist Votan Ik, whose tribal affiliations are Maya and Nahua, is the founder of NSRGNTS, an art collective and brand that advocates for Native Rights. A muralist and street artist, Ik frequently collaborates with his partner, Leah “Povi” Lewis, (Pueblo/Hopi/Zuni/Diné).

“Without art, there is no culture. Artists evolve the culture, preserve the culture,” says Ik. “As an Indigenous artist, ‘I’ cannot take credit for my art entirely on my own,” he adds. “When ‘I’ speak of the work, ‘I’ replace the ‘I’ with ‘We,’ for we (ancestors, colleagues, community, family, friends, and at times foes….) all make this possible.”

With the assistance of Lewis and NSRGNTS member Derek Brown (Diné), in 2017 Ik created the mural Ganawenjiige Onigam (She Watches Over Duluth) at the American Indian Community Housing Organization in Duluth, MN in part to shed light on an epidemic of kidnapped Indigenous women, as well as to honor the water protectors at Standing Rock.

Ik hopes that his work will inspire viewers to get involved through whatever means possible. “Raising awareness is the first step, but creating actual change is the goal,” he shares. “Although people tend to view the work we do as targeting Indigenous people, we’d like to express the idea that all people are indigenous (even the four-legged and winged and so on). Everyone is indigenous to somewhere, and being indigenous is being human.”

They created all five of their 2020 murals for free, “to inspire hope and resilience throughout the country.” Getting paid for their work, however, serves their cause, allowing them to provide projects for communities who might not otherwise have the funding.

There is an ethics debate regarding artistic activists profiting from their work, based on an expectation to volunteer and donate. “Funding is…crucial,” Ik observes. “We do live in a country fueled by capital, and we must support underpaid or unpaid artists for their dauntless expression and involvement. Society tends to see art as a hobby and not a career.”

The artivist cites Jane Fonda, Ricky Martin, and Jaden Smith as examples of creatives who engage in activism. “What they do with their earnings is not in question, we just accept their involvement.” He adds that activist musicians Public Enemy, Bob Marley, and Bob Dylan are not perceived as exploiting the cause. “Instead of seeing ourselves as separate and benefiting from it, we see ourselves as an extension and expression of it.”

Artist Jon Ching agrees. “Do we demand that David Attenborough, Bill McKibben, or Jane Goodall donate all of their work for the sake of the planet? No, but perhaps we would if they identified as artists.”

Ching feels that he is just stepping into his artivist identity. He has released a giclée with Andy Okay to benefit the Rainforest Trust, with another planned in support of Amazon Frontlines. He was also a host of Our Planet Week, where art inspired by climate and environmental themes was turned into 5,000 trees. “When I donate work to raise funds for trees… and see it become a forest that will hopefully last a century or more, the monetary value of that one painting is eclipsed by the enduring value of that action,” shares the artivist. This summer, Ching will support specific endangered species through smaller fundraising efforts, and later this year will release a giclée with the PangeaSeed Foundation.

Ching now lives in Los Angeles, but grew up surrounded by the natural beauty of O’ahu, Hawai’i. “I’ve always wanted to use my artistic voice to raise awareness about environmental issues,” he says. “Now my approach is to explore the beauty of nature to spark reverence and appreciation in hopes that it leads to concern and protection.”

A self-trained artist, Ching’s surreal style speaks to the core of his work. “I want to show that everything is connected and that protecting nature is actually protecting ourselves. When I paint a bird whose feathers are flowers or leaves, it’s because at some level, everything is connected and thus the health of one is the health of the other. My call to action is to remember the magic and awe that is this planet.”

The Center for Artistic Activism’s new book and accompanying workbook to empower activist artists, The Art of Activism: Your All-Purpose Guide to Making the Impossible Possible (O/R Books), will be available in June. Lambert encourages stretching beyond the goals of raising awareness, inspiring dialogue, and communicating a message: “Artistic activism can change behaviors, our dreams, and our sense of what’s possible, and it can impact power and policy.”