“The Bauhaus comes from Weimar,” the city reminds us at its new museum to commemorate the pioneering art and design academy. The reminder is necessary: for the last nine decades, there has been little evidence that the school Walter Gropius founded 100 years ago was ever based in this small but important German city.

Weimar owes its UNESCO World Heritage status to a cultural movement known as Classicism led by the great German writers Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Friedrich Schiller. But it is finally also staking its claim as the birthplace of modernism. In the early 20th century, Weimar was a beacon of the avant-garde under a progressive museum director and patron, Count Harry Kessler. It was fertile ground for Walter Gropius to found the Bauhaus to “conceive and create the new building of the future.”

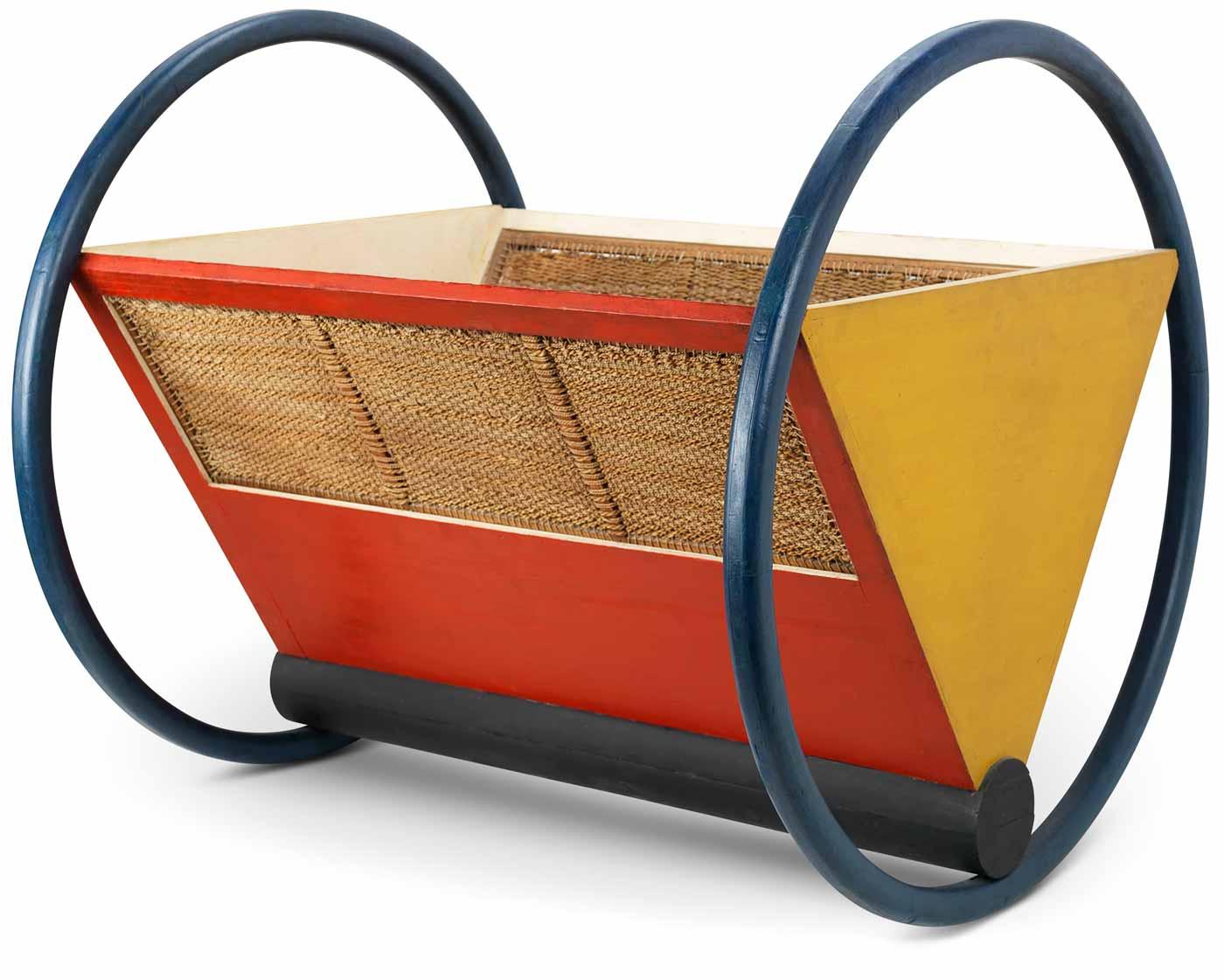

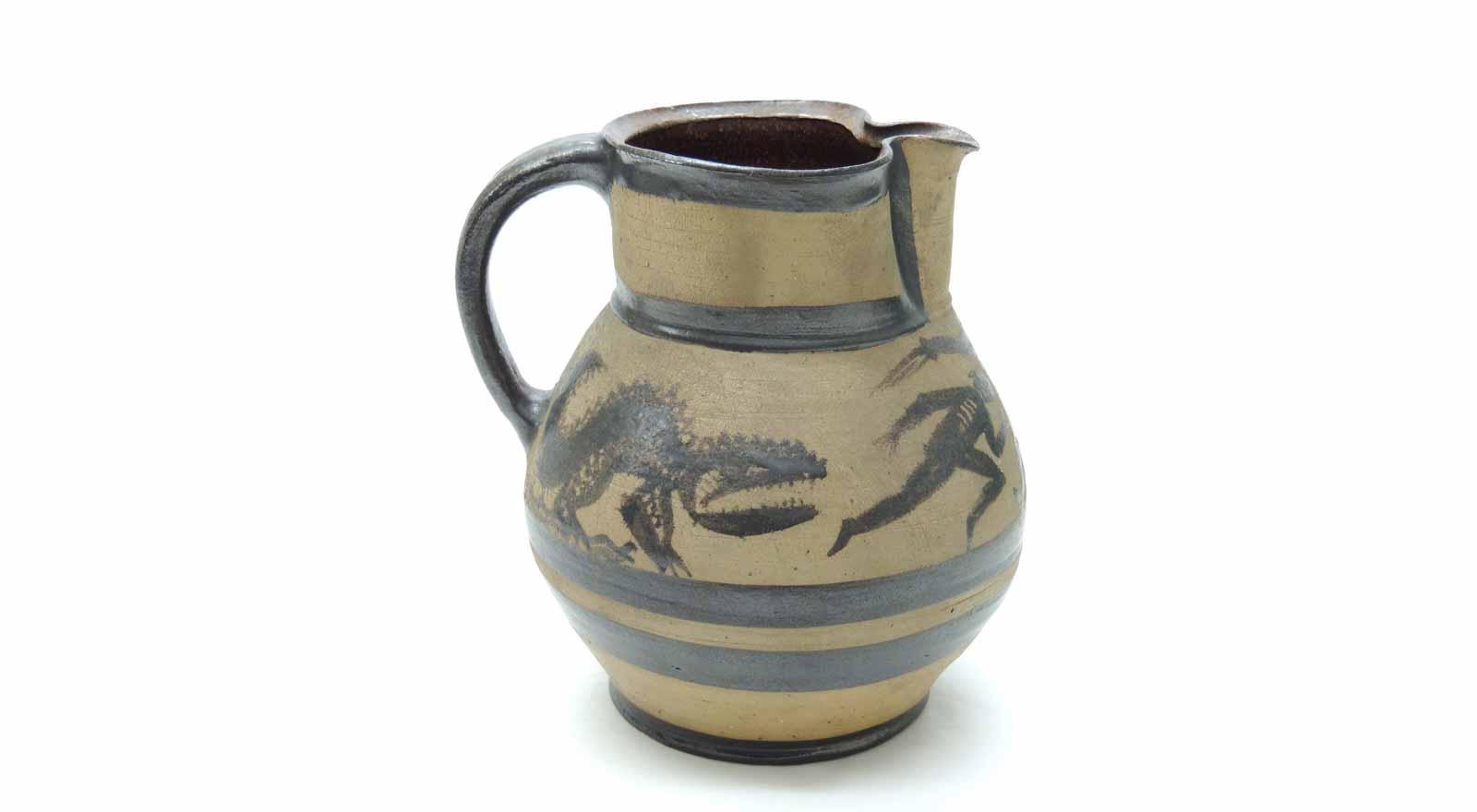

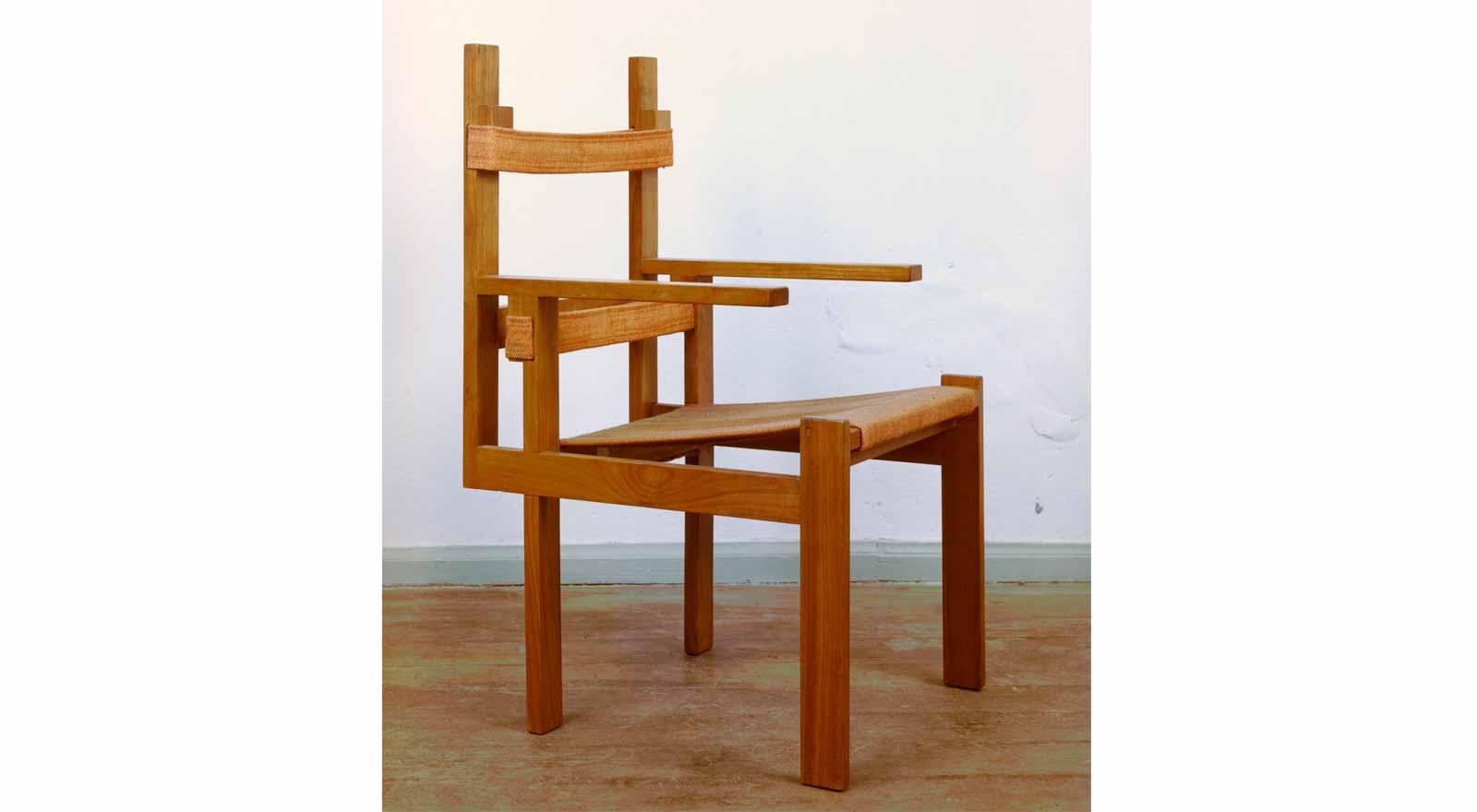

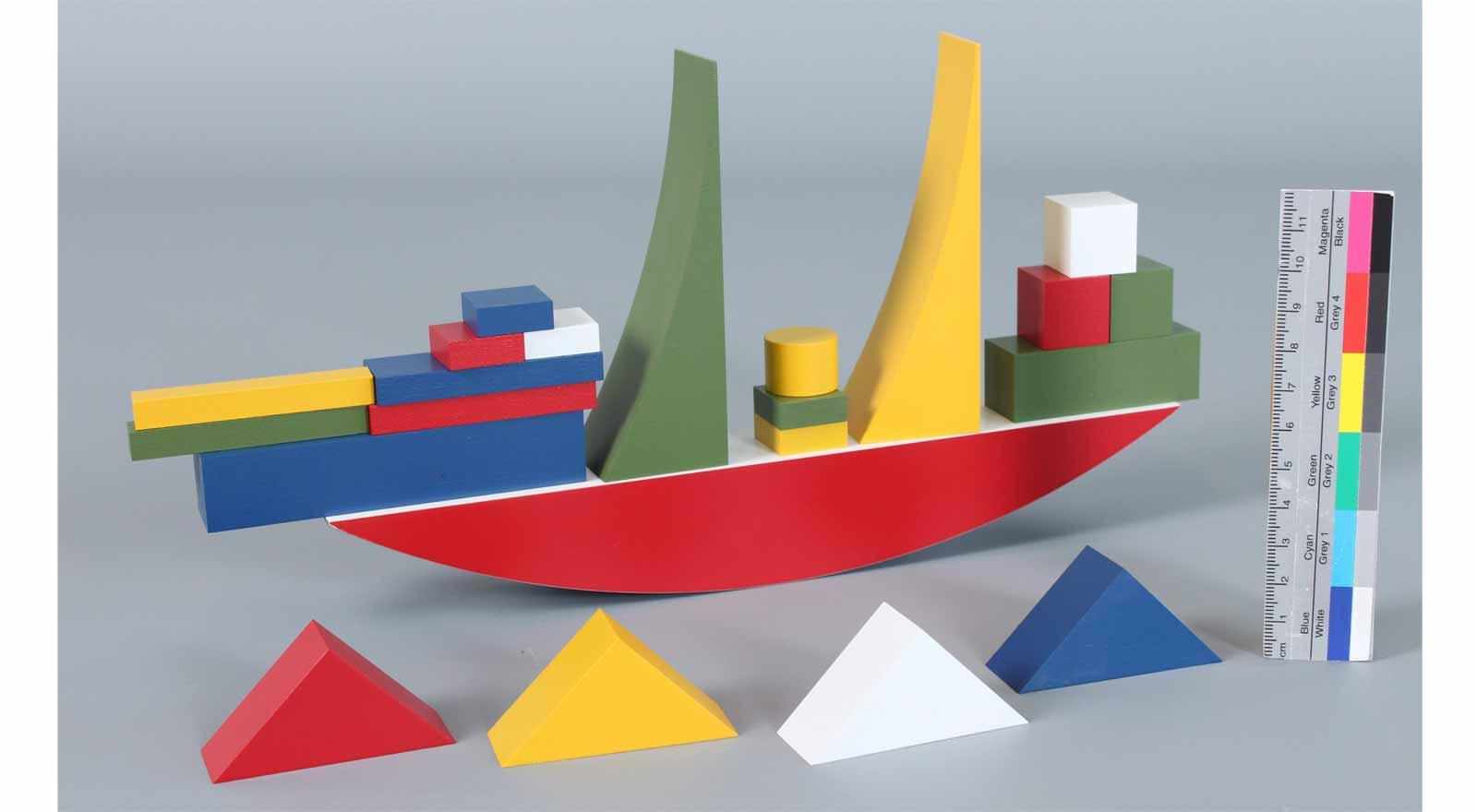

The school stayed in the city just six years. Under pressure from reactionary nationalist forces, it was forced to move to Dessau in 1925 and to Berlin in 1932. It closed for good in 1933, the year the Nazis seized power. Many of its protagonists fled into exile and scattered, spreading its functional aesthetic and utopian ideals as far afield as Tokyo, Tel Aviv and Mexico and the U.S. The Bauhaus emerged around the world; in glass and concrete towers, minimalist furniture, textiles, crockery and lamps.