When one hears the name "Nasca,"* the first thing that comes to mind is probably the monumental geoglyphs of the Peruvian desert; swirling designs of plants and animals incised into the desert sand on such a massive scale that they can only be seen in their entirety from the sky. But if you visit a museum in search of Nasca art, whether in Latin America or elsewhere, what you’ll find are the incredibly detailed and colorful fine ware ceramic vessels of the Nasca. So why are the Nasca Lines so well known, when so few have heard of this beautiful (and abundant) polychrome pottery that they produced for almost a millennium?

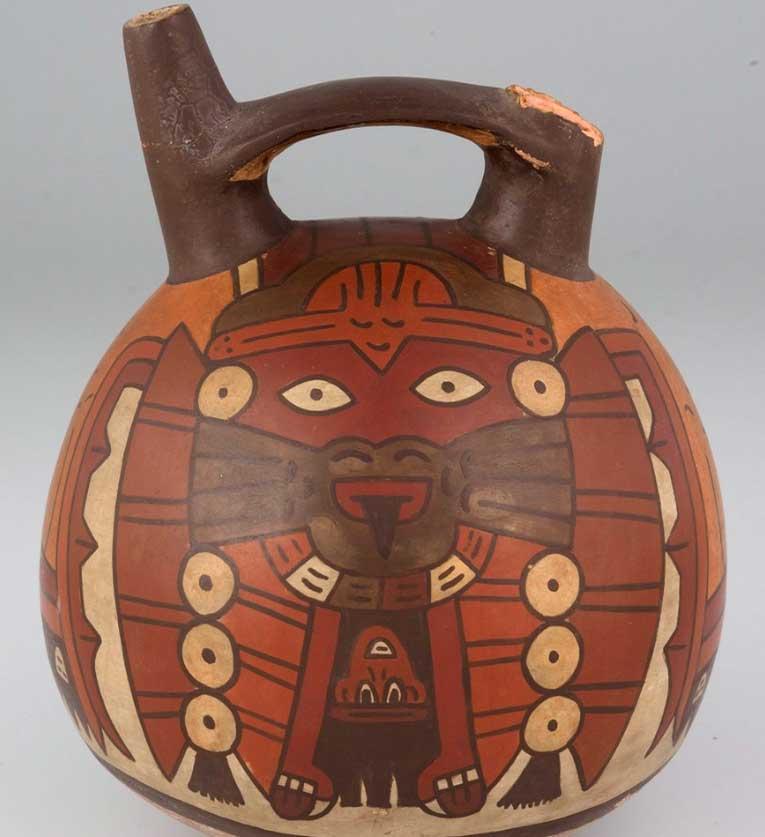

These ceramics are the most colorful pre-Columbian pottery ever produced in Peru. They are painstakingly handcrafted and painted with complex, sometimes dizzying, geometric and natural designs. Rich reds, yellows, oranges, and browns depict scenes of life, death, birth, and war. The iconography is broad in scope: both mundane plants and life-giving waters of the desert contrast with fantastical chimeras of animal-faced gods and startling motifs of severed trophy heads, lips sutured, and eyes closed in death.

It was this diversity of color and iconography that first drew me to the Nasca vessels at Cornell University. The collection consists of almost three dozen intact vessels which span a roughly 700-year period. By viewing this assortment, one can easily see how the iconography has changed drastically over the centuries. But, in order to more fully understand its significance, one must know more about the Nasca people themselves.

A series of chiefdoms linked by a common religion and culture, the Nasca resided in the Ica and Nasca Valleys along river drainages. An alluvial basin, these lands were rich with mineral deposits such as iron oxides and white kaolin clay.