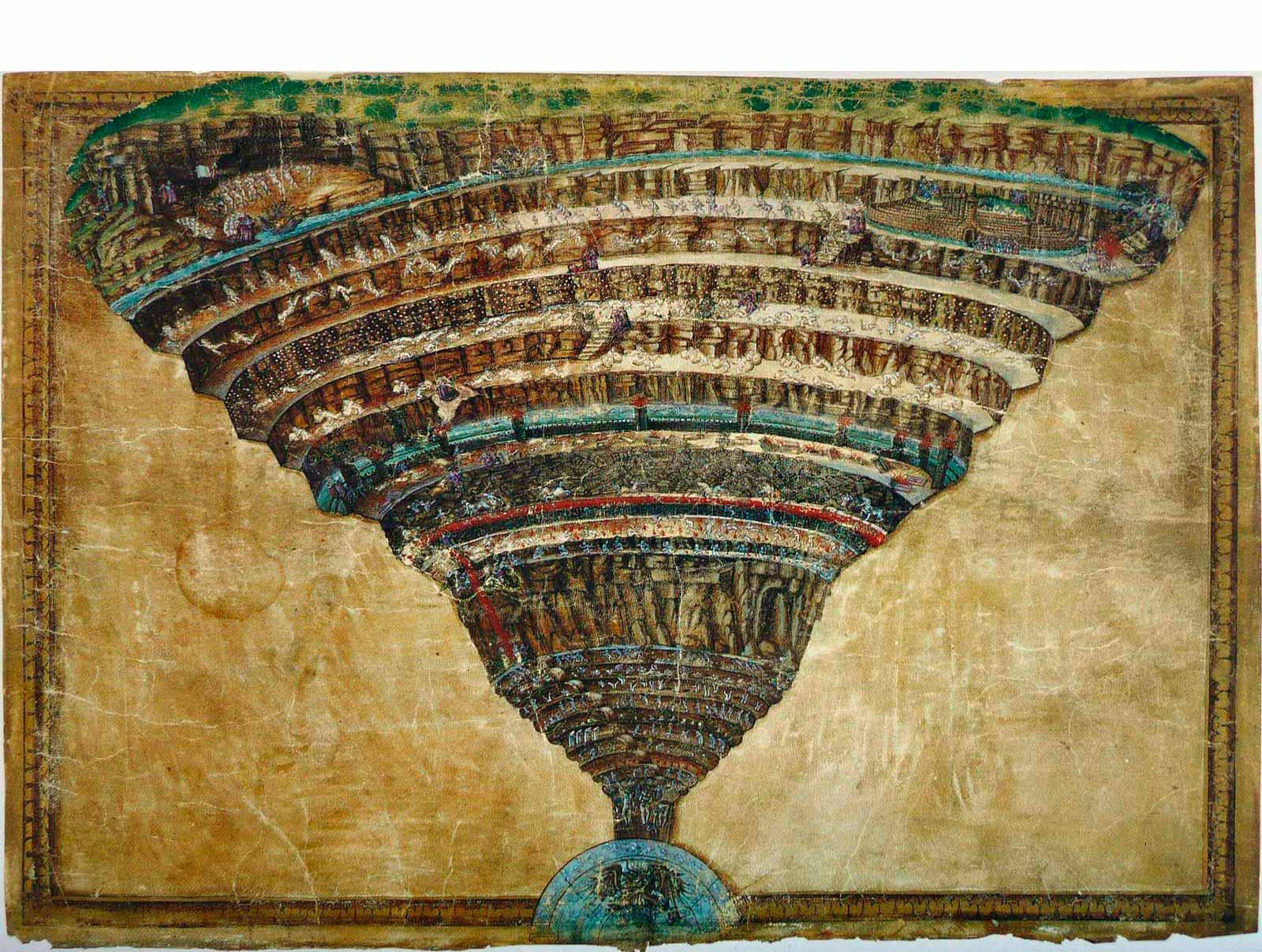

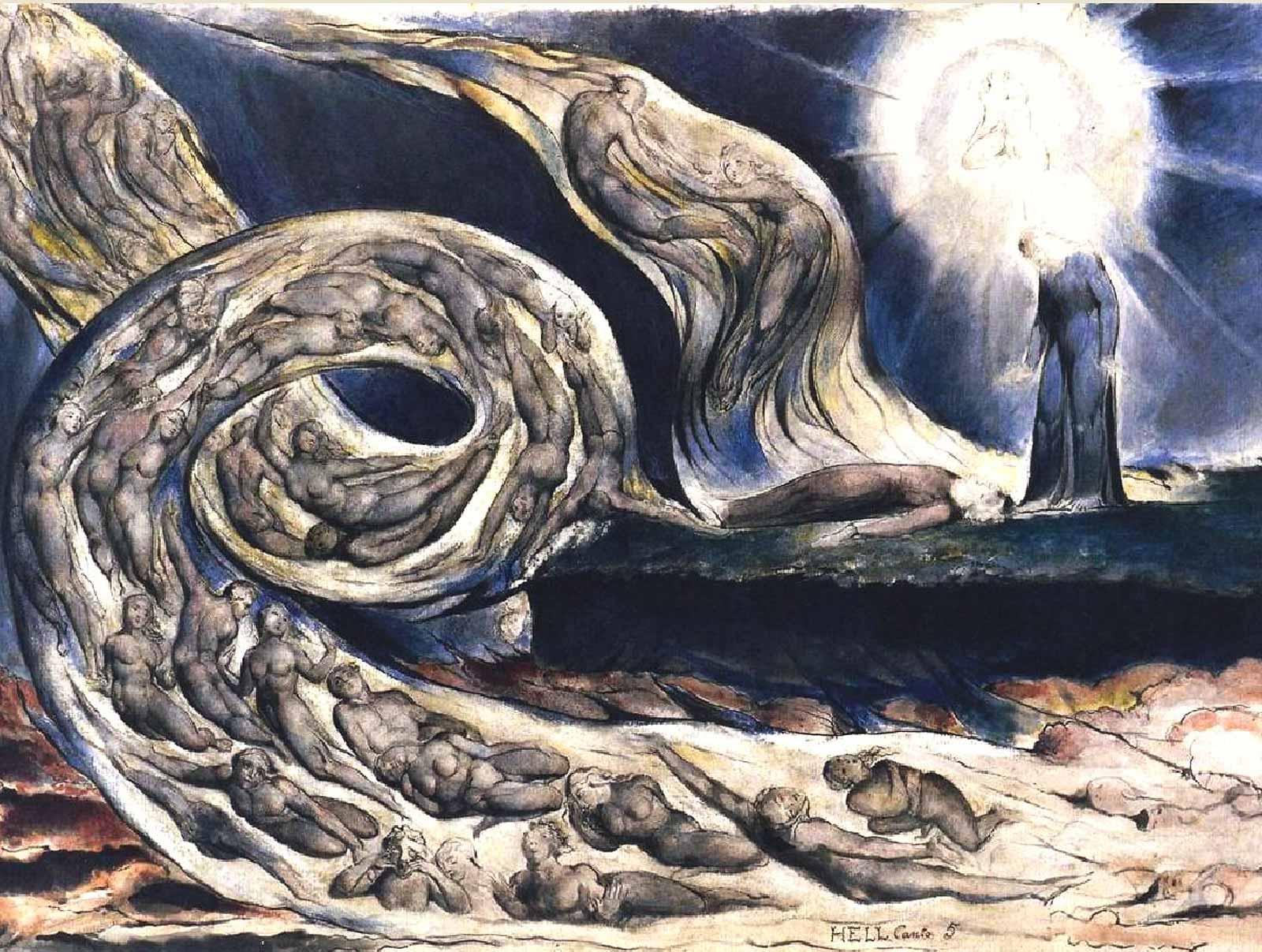

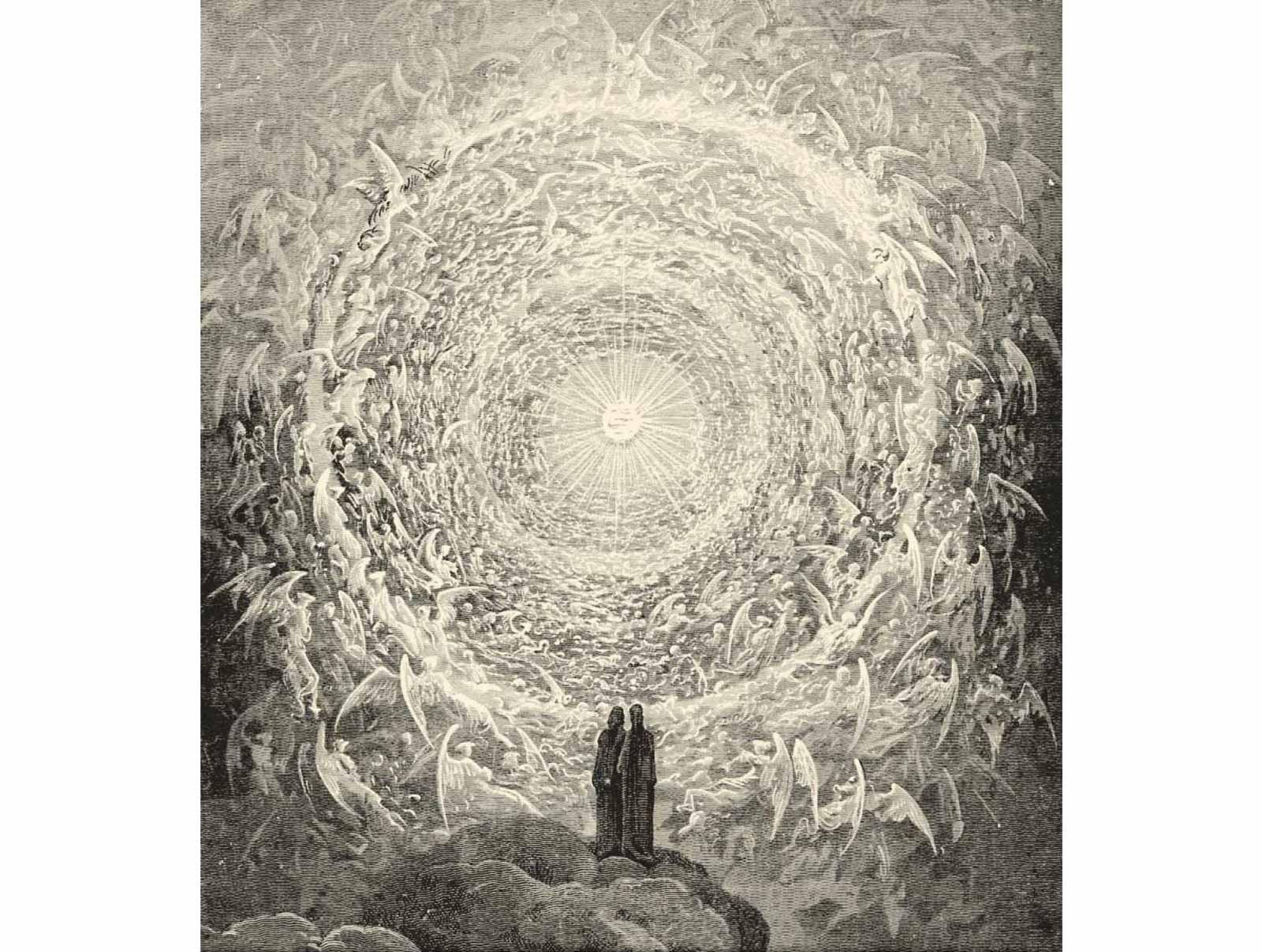

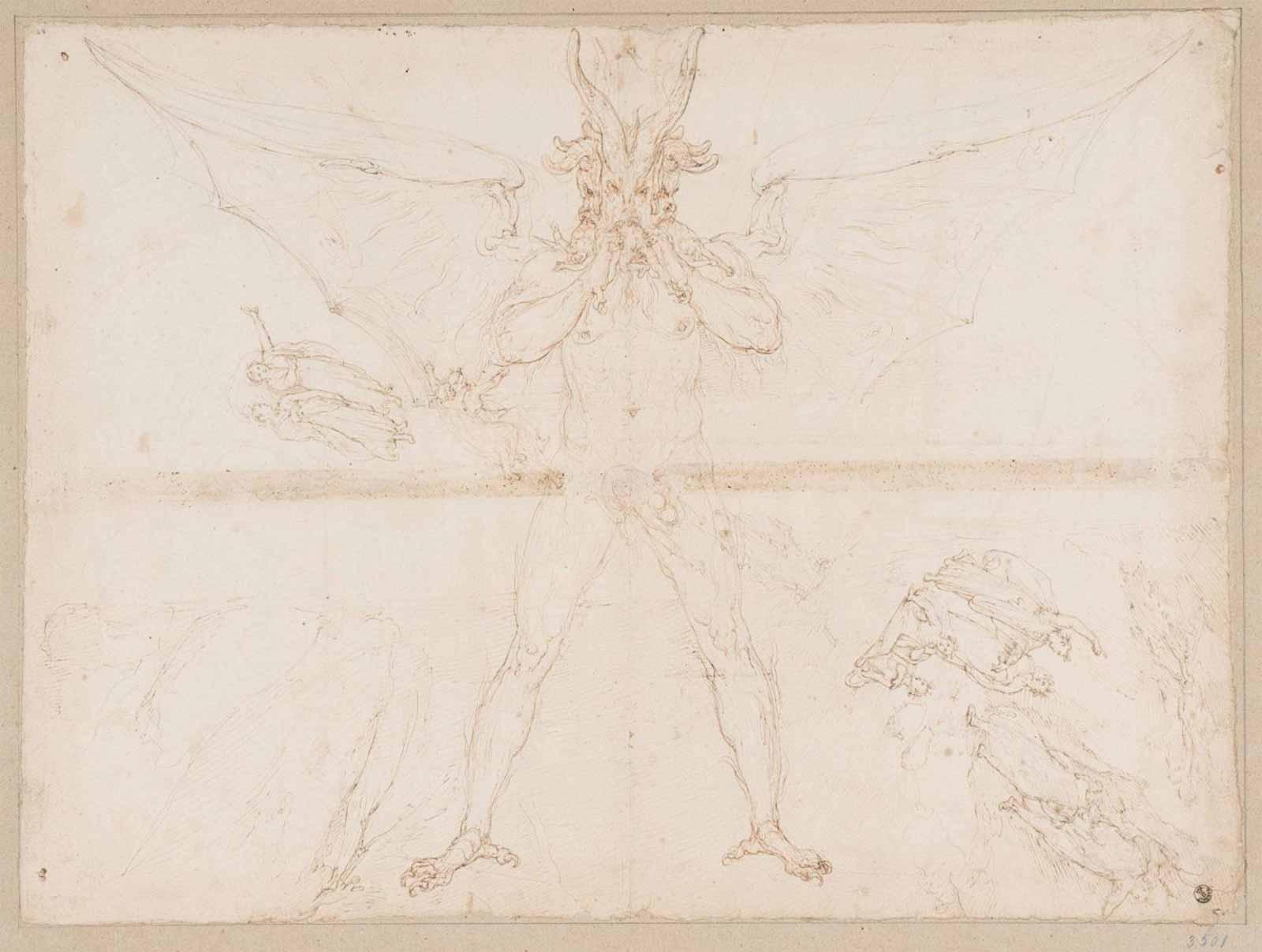

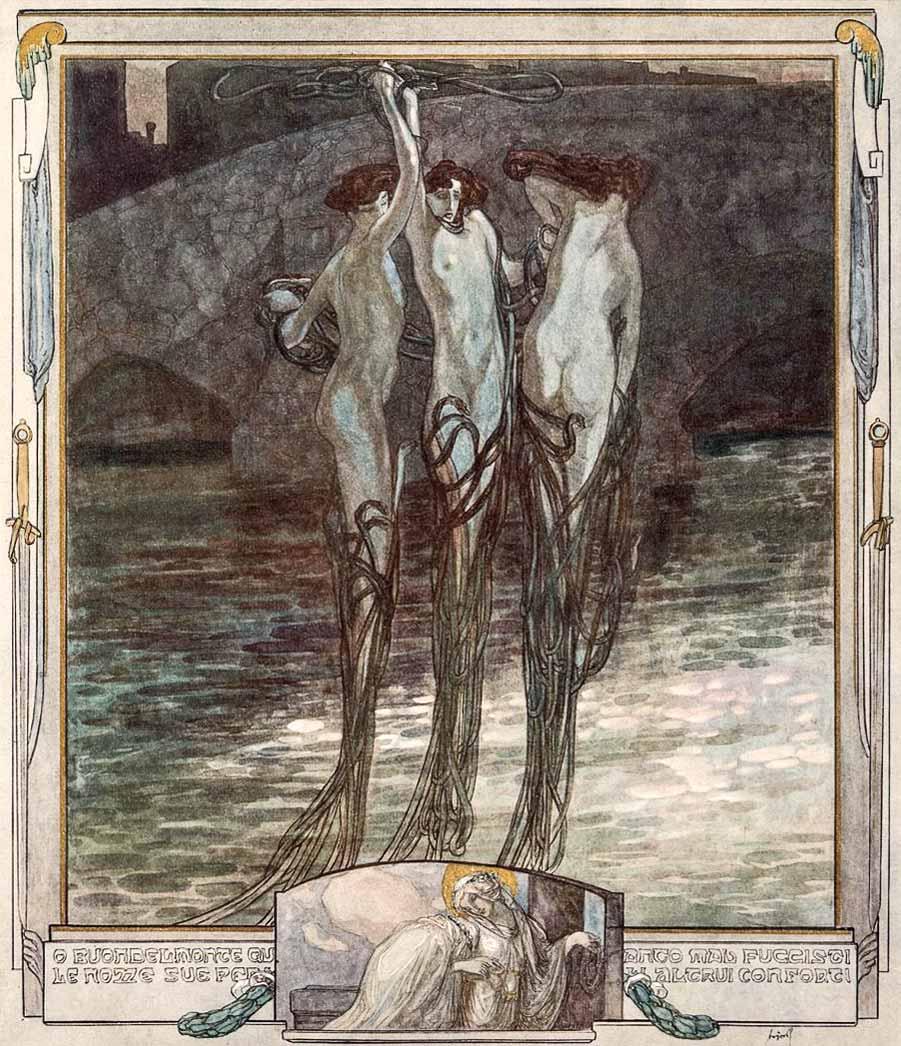

Ever since Dante’s Divine Comedy was published, it both ascended to the canon of Western literature and inspired countless artistic interpretations of the poet’s journey through the otherworld as he and his guides traverse the depths of Hell, climb Mount Purgatory, and then ascend to Paradise. “Artists in all media have responded to the Commedia with an abundance and enthusiasm that even the Bible has not matched,” writes Jean-Pierre Barricelli in the paper “Dante in the Arts: A Survey” published in the 1996 edition of Dante Studies.

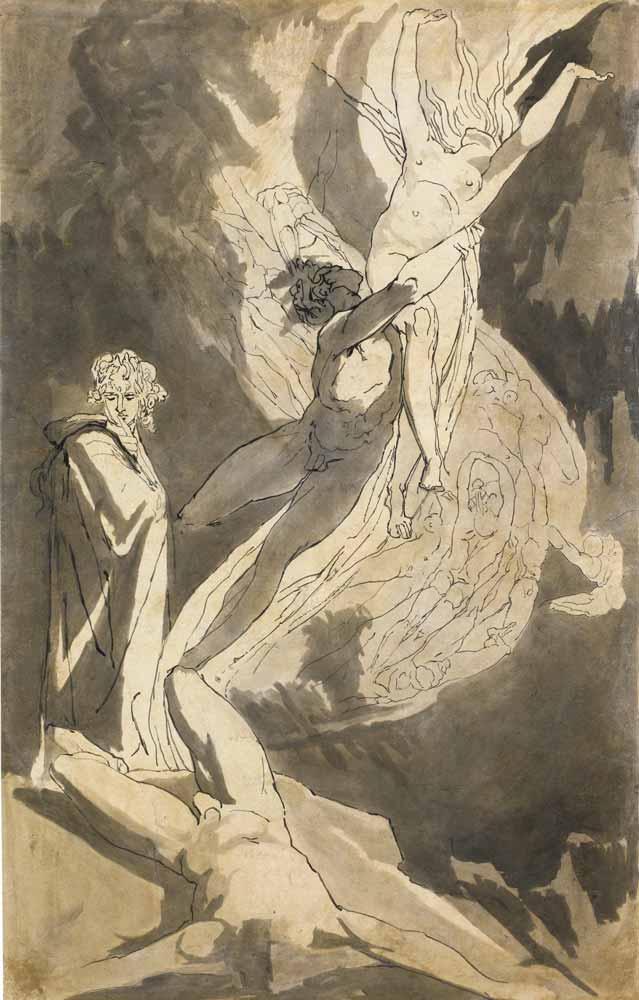

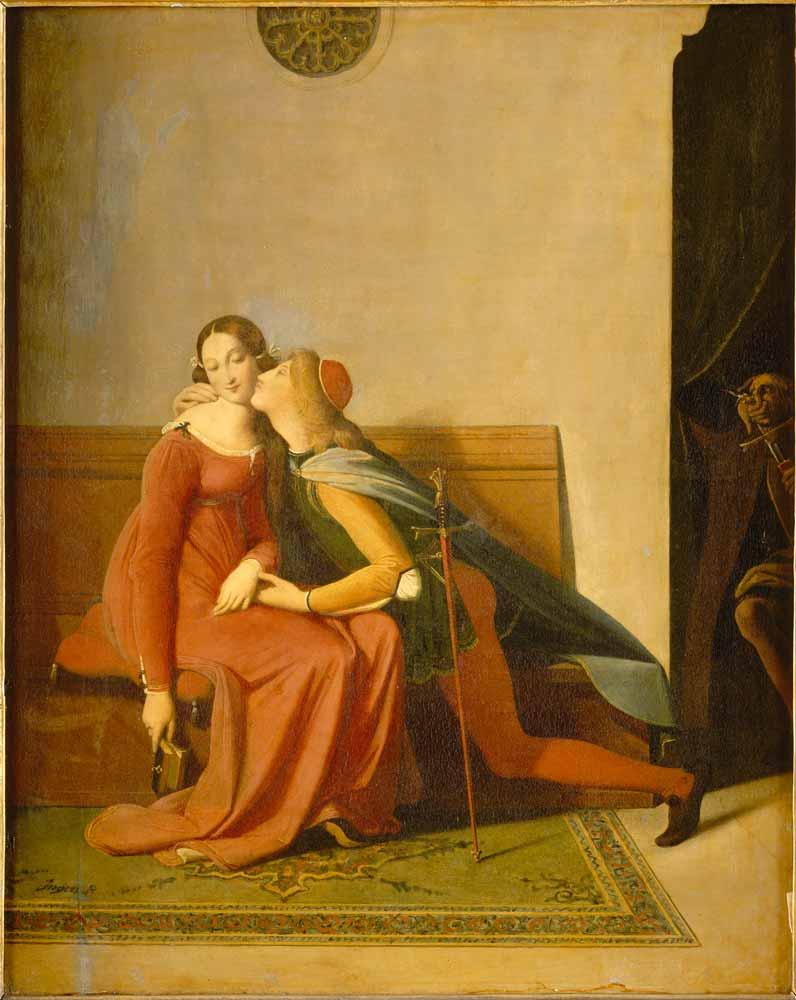

Painters have long recognized the importance of understanding the source material intimately: through their execution, they sought to transcribe the poet’s vision.

“Dante’s imaginative comparisons and vivid descriptions of the afterlife have sparked the imaginations of innumerable artists,” Deborah Parker, Professor of Italian at the University of Virginia, tells Art & Object. “Many artists introduce changes, some subtle, others more striking,” she continued. Gustave Doré and Sandro Botticelli—she cites as examples—while generally faithful to Dante’s text, also introduced changes to their works. Doré, for example, added more women among the damned. “Artists don’t just depict, they interpret,” she said.