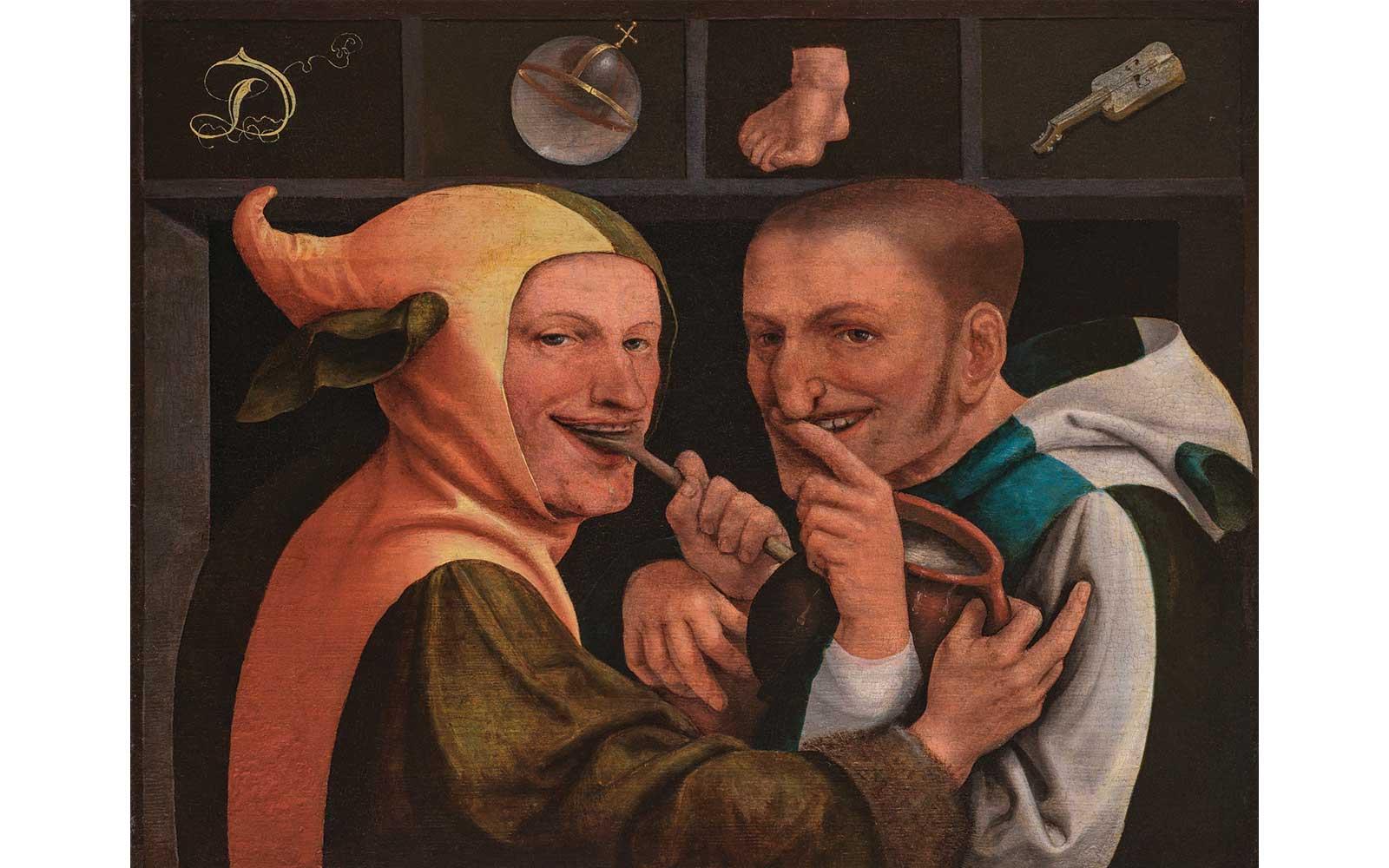

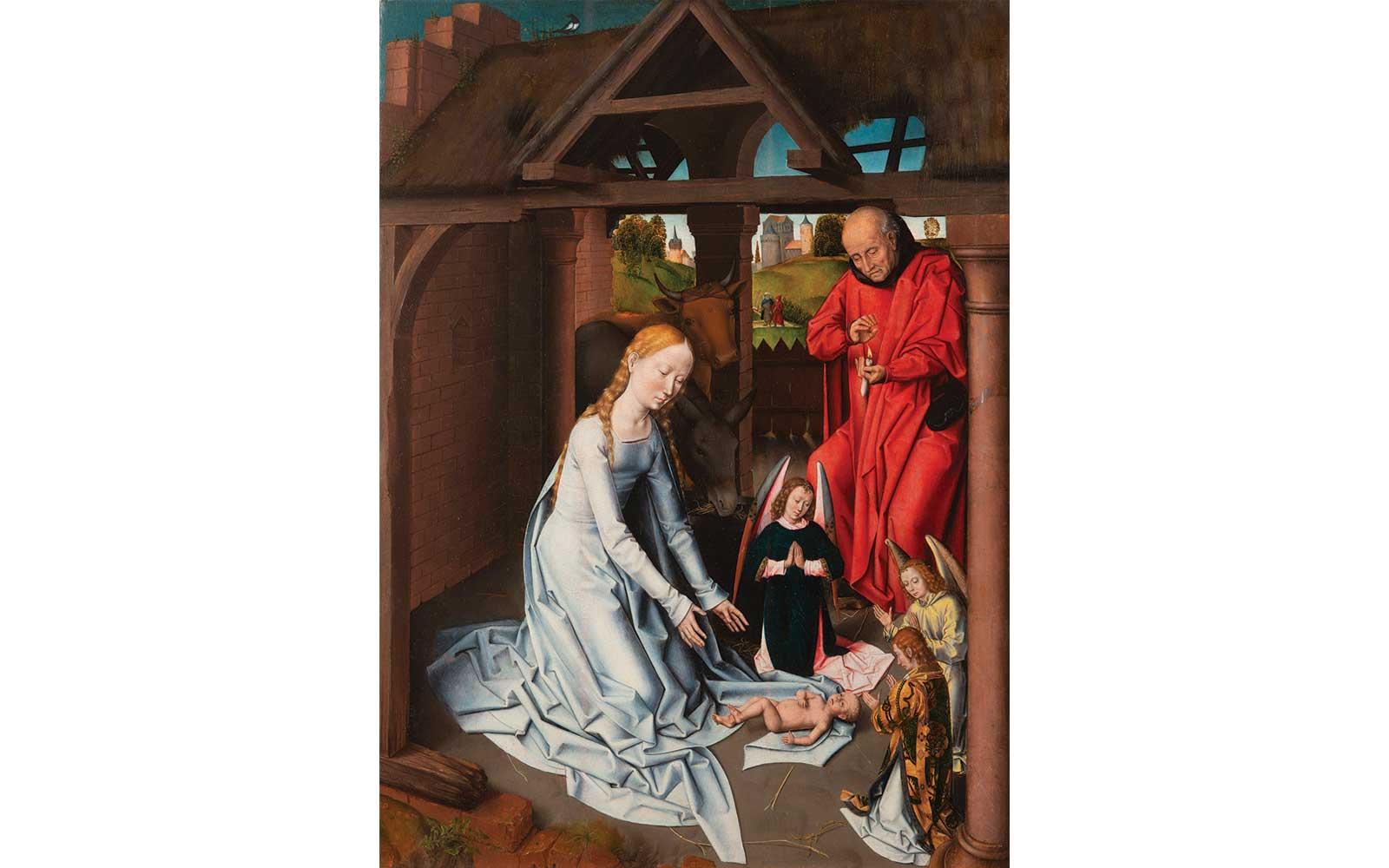

The Denver Art Museum in collaboration with Belgium-based Phoebus Foundation presents a fresh take on old masters with “Saints, Sinners, Lovers and Fools: 300 Years of Flemish Masterworks” showing through Jan. 22, 2023.

The show exquisitely spotlights more than one hundred and twenty masterpieces including seventy paintings created by artists in Flanders (the Southern Netherlands) from the 15th to 17th centuries. DAM’s Chief Curator, Angelica Daneo, hypothesized that the oldest work in the show, Saint Anthony Rebukes Archbishop Simon de Sully in Bourges, was painted between 1450 to 1475.

“A shift happened in perception from the 14th century, when artists were still considered craftsmen, using their hands to create, to the 15th century when artists begin to be accepted in the same circle of creators such as poets and historians, on the basis of their intellectual skills, rather than their manual abilities,” Daneo said, “a true shift that led to the concept of artistic genius.”