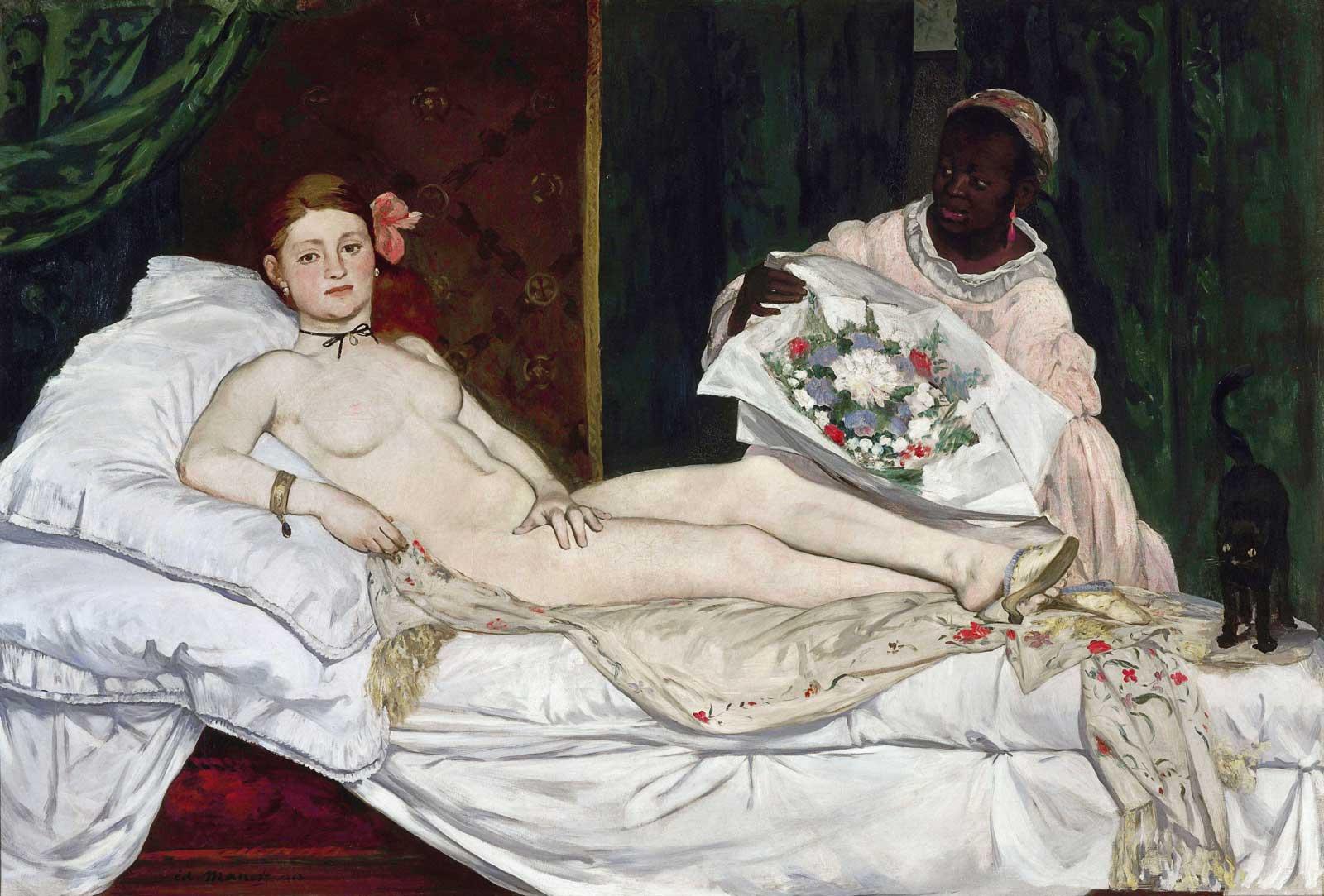

In Édouard Manet’s 1863 masterpiece, Olympia, which is currently on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the exhibition "Manet/Degas," in which it is making its debut in the United States, a naked white woman lies in a sultry pose on a chaise lounge. Her frank gaze directed at the view gives the impression that she is aware of our presence and are perhaps expected guests. She is presumably a prostitute, which forces the beholder to take on the role of Olympia’s next male client. Her Black female maid stands behind her, her skin almost blending into the dark background, as she presents Olympia with a bouquet of tea roses that we can assume was sent by a male admirer.

The Feline Companion in Manet’s Olympia

Olympia, by Edouard Manet, 1863.

In Manet’s Olympia, he inserts a black cat to represent what we cannot see, proving his art to be provocative, daring, and modern.

Henri Fantin-Latour, Portrait of Edouard Manet, 1867, oil on canvas.

Edouard Manet was a playful artist who loved incorporating puns and tricks into his work.

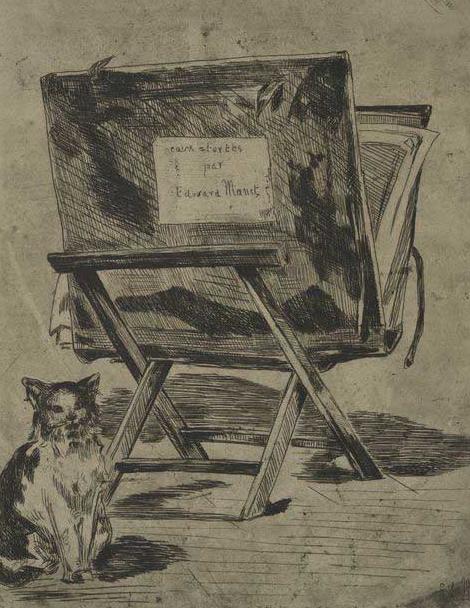

Edouard Manet, "Deuxième frontispice inédit," 1862.

At the foot of the bed is a black cat, who, like the maid, almost fades into the background, his hind legs untraceable against the dark green curtain. He stands upright and erect, his yellow eyes wide – he was clearly not expecting us. It is as if we have just walked into Olympia’s room and surprised a once-sleeping cat. He jumps, with his wiry tail up and his back arched. In the next instant, he would most likely hiss and then run away, annoyed by our presence.This curious but seemingly insignificant creature in Manet’s Olympia actually is far more important than casual viewers of the painting might expect. And in fact, the cat’s inclusion was a carefully considered detail by Manet and one that warrants exploration.

Domesticated cats are enigmatic creatures. They are completely ordinary, and at the same time, they hold power over us with their innate mystery. For the thousands of years that cats have lived alongside humans, they have been symbolic of the feminine mystique, appearing as recurrent subjects in literature and art for centuries and across cultures. Known for their refined manner and sleek appearance, cats were often associated with goddesses in Ancient Egypt and Greece. But while cats can be both comforting companions and idols, since the 13th century, they have also held negative connotations of dark magic, thievery, and forbidden sexuality. Their mysteriousness and independence can be seen as devilish and cruel, and their lack of social interest can be construed as two-faced and untrustworthy. Thus, cats have come to represent all the prejudices that we have construed against women, sexuality, and independence.

Edouard Manet, Olympia (detail), 1863, oil on canvas

Manet uses a black cat, snarling at the pink feet of his Olympia and staring at us with his yellow eyes, to represent what we cannot see behind the hand.

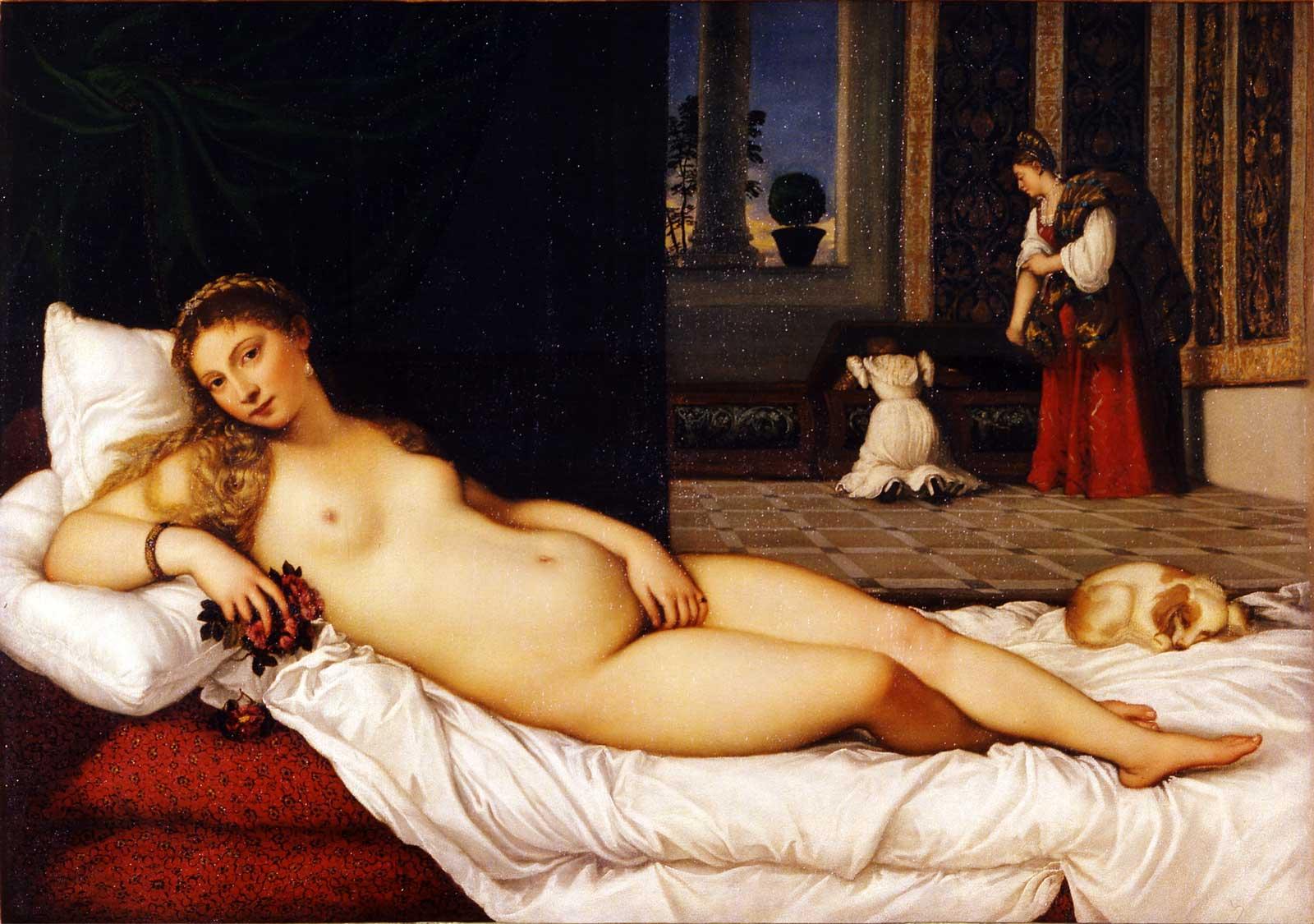

Edouard Manet was a playful artist who loved incorporating puns and tricks into his work. We know he added the cat to Olympia intentionally because this entire composition is a direct quotation, or reference, to Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538), which Manet copied in Florence ten years prior to painting Olympia. In Titian’s work, which was commissioned for private viewing, the female figure is an otherworldly Venus in the nude; she is a positive symbol of fertility and femininity. Curled up at Venus’ feet, rests a puppy. Dogs in Titian’s time, as in our own, denoted fidelity. But in Manet’s take on the scene, as art historian T.J. Clark says, he renders a decidedly naked woman that more closely engages in the current politics and culture of his time. This is announced by the black necktie choker, earrings, bracelet, and slippers. Most importantly, he also switches out the sleeping dog for the angry cat, who looks at us as we look at him.

The cat could be an example of voyeurism: a single figure looks out from the painting to meet the viewer’s gaze. We, the viewers of the painting, are not only part of the story, but crucial to it. Though this is common in many artworks and not just Manet’s, what sets Manet’s work apart is twofold: who is looking out at us, and what is their expression? In works such as A Bar at the Follies-Bergere (1882) or La Nymph Surprise (1861), the figures in the works are blushing, or their mouths are agape and eyes wide; they are surprised by us, the viewers. In Olympia, both the model and the cat look out at us. In art historian Michael Fried’s book, Manet’s Modernism, he points out that there is no single large multi-figure painting by Manet in which more than one figure looks out at us. The closest thing to an exception, Fried says, is in Olympia, in which the model and the black cat confront us directly.

So why choose a cat who seems utterly disgusted and perturbed by us? Well, one only has to glance to the left to see Olympia to understand why. The entire painting is highly sexualized, and the sex appeal only continues with the black cat. Although Olympia covers her genitalia, we know what lies beneath—but both Manet and society do not allow us to see it, especially in public at the Salon, where this painting was revealed.

Inherent in the name itself in French, chat/la chatte, and in English, pussy cat/pussy. But, as art historian Joachim Pissarro argued, when thinking about this potential language pun, we are entering a "complex lexicological domain." He says, "French, as so many other languages, is linguistically structured around two genders. This means that every single word is either a he or a she. In the case of the cat, the generic word used is masculine: un chat.

The pun that seems obvious is that the cat is symbolic of what Olympia covers – her genitals. On this, Pissarro says, “I am not excluding the possibility of the association between the cat’s existence and the gesture of Olympia covering her genitals.” But, he continued, "I don't think that Manet is playing puns on that lowly level of language. It is a tempting pun to construct, but this association cannot be mediated via the French term chat, as this term does not carry any sexual reference, unlike the feminine term, which would never come to mind."

So we must go back to the meaning of any cat – let alone an aroused cat – be it in 1865 or 2023. The cat figure is universally perceived as sexual. And, the female genitalia is also, of course sexual, but is more mysterious; an object of dichotomic interest that many find beautiful, but also disgusting or ugly. Whatever Manet’s reasoning, it is clear he wanted to illicit this kind of conversation. By using the cat, Manet was provocative and most importantly, modern.

So where do we go from here? Perhaps the black cat is not only a symbol of femininity and sexuality, but he is also a projection of the artist and his ideas of modernity. Maybe the cat in Olympia acts as a vessel for the artist to communicate with his viewers. Manet regularly wrote letters to his friends lamenting about the negative feedback he received from critics. He also frequently inserted himself into the canvas, whether it be through an actual self-portrait or an object, most notably a cane. Therefore, it would make sense that Manet wished to respond to the Academie more directly through his work. Through the cat, Manet was able to cast a judgemental eye on society, to challenge the stale conventions of the Academie and society, who deemed his nude prostitute painting to be controversial, even calling it a disgusting image to be on view. But the cat gives our judgments right back to us, he is Manet’s very own “mirror of enigmas.”