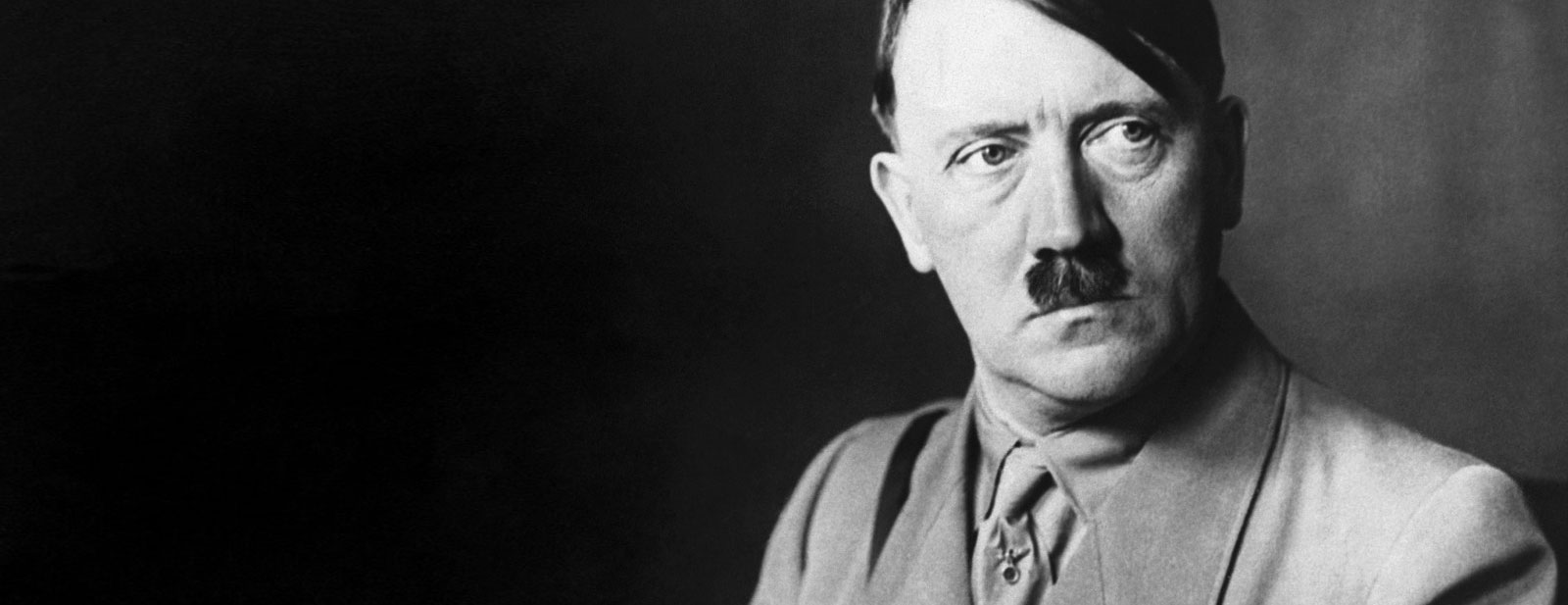

In a letter on June 5, 1940, Edward Bernays wrote to Henry Luce, owner of Life magazine, advising him against publishing a puff piece on Adolf Hitler. Bernays warned, “America is prone to hero worship,” and “if Hitler should be successful [in his plans for war and genocide] it may be with our admiration for success, a man may well turn a present hate into admiration.” In other words, Life Magazine should not make a hero out of this individual.

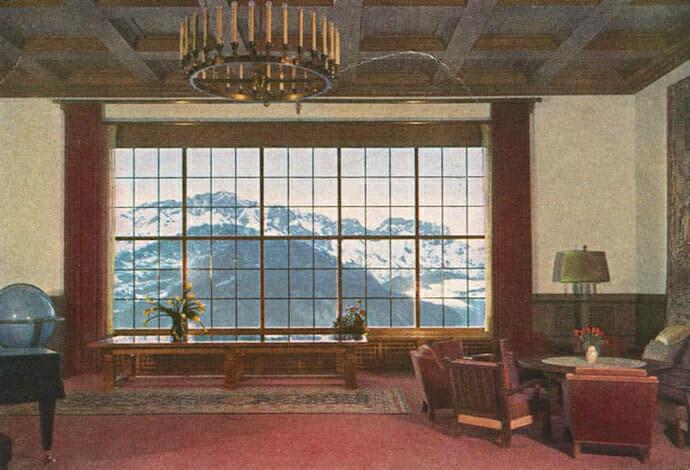

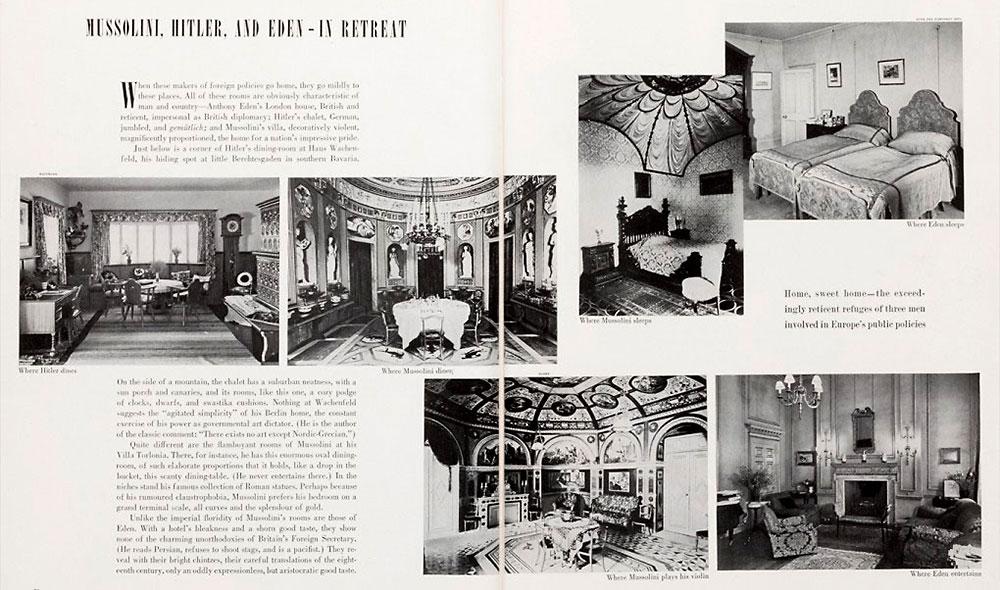

The piece was not published, but countless others just like it were in the pre-war years. In her 2015 book, Hitler at Home, Despina Stratigakos charts the Nazi’s propaganda campaign to rebrand Hitler from a middle-aged bachelor with few family ties, to a country gentleman. What is most interesting is how American publications such as The New York Times, New Yorker, Life Magazine, The Washington Post, and Vogue all published fluff pieces on Hitler’s home decor and mountain lifestyle from 1934 until as late as 1941, and then had to grapple with these mistakes in subsequent years.