“You are asking me to do something which is perhaps as difficult to do as painting is,” Edward Hopper wrote to curator Charles H. Sawyer in October 1939, “that is, to explain painting with words.” Hopper–who spent two decades supporting himself as a commercial illustrator and went years without selling a painting–had finally attracted attention for his austere, ambiguous pictures of late night diners, solitary office workers, and lonely movie-goers. People like Sawyer wanted to know: what did his paintings really mean?

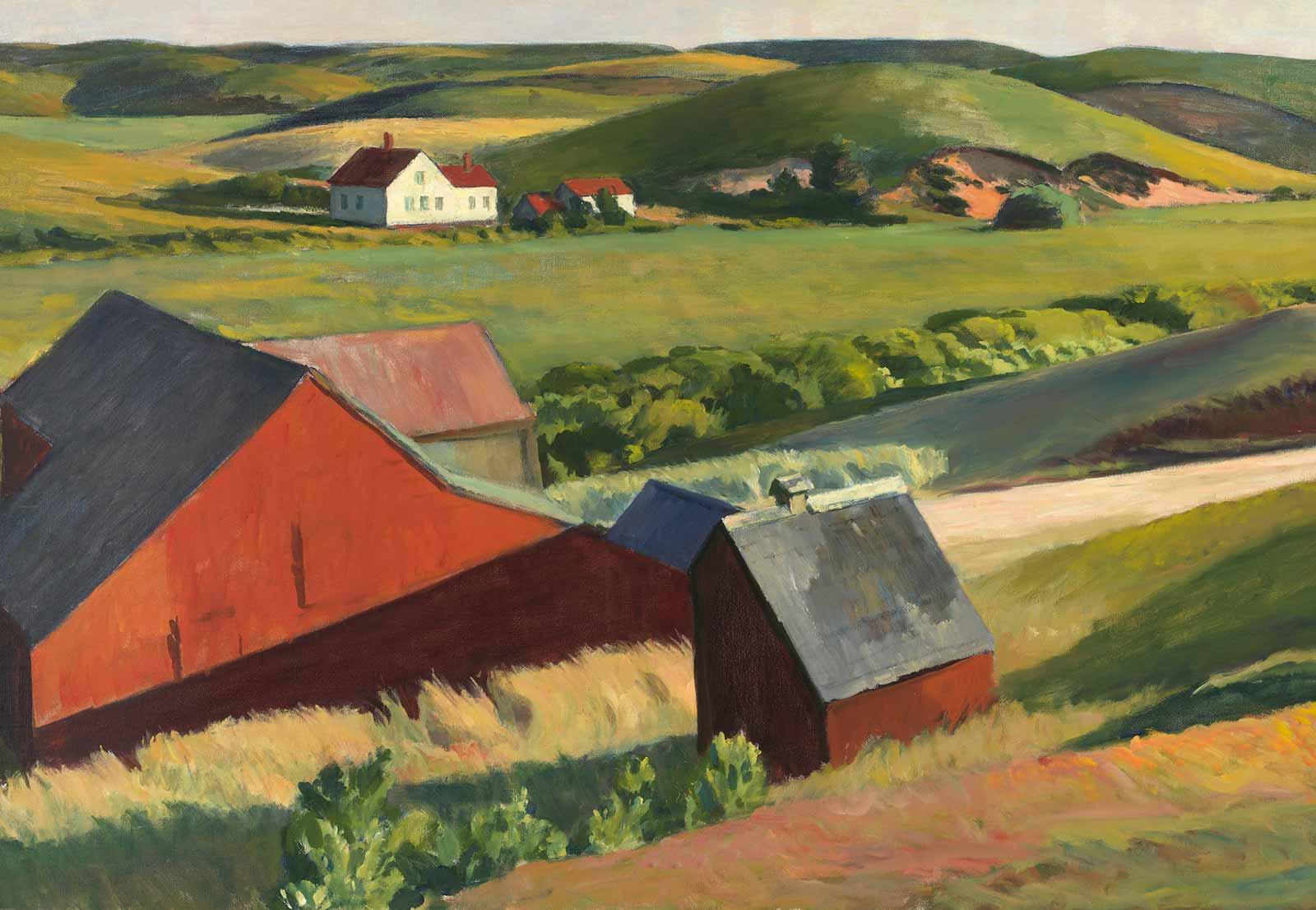

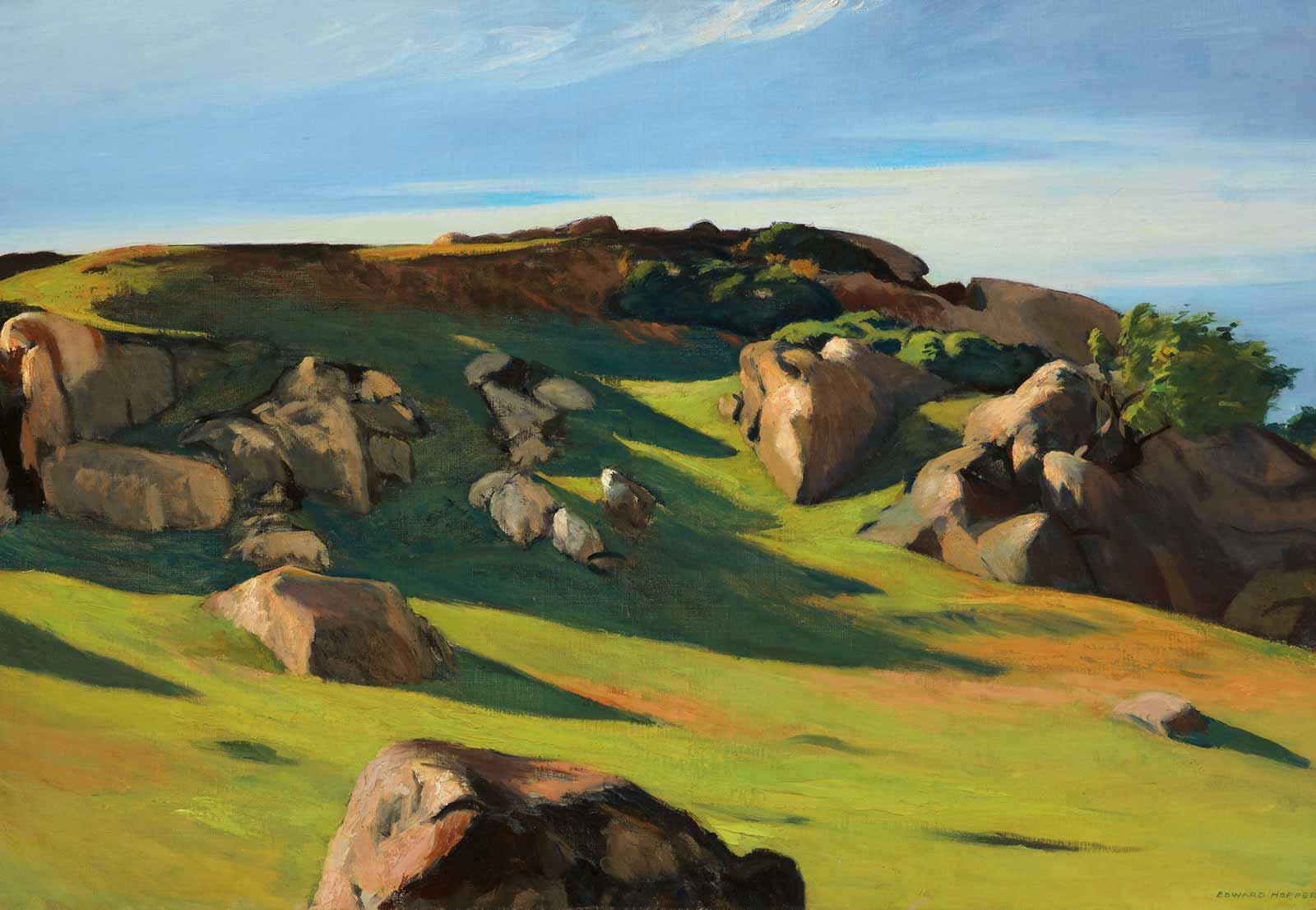

The artist was markedly tight-lipped throughout his career, preferring for his work to speak for itself. But for those who think of Hopper as the consummate painter of the modern metropolis, what he revealed in his essay for his 1933 retrospective at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York may come as a surprise: “My aim in painting has always been the most exact transcription possible of my most intimate impressions of nature.”

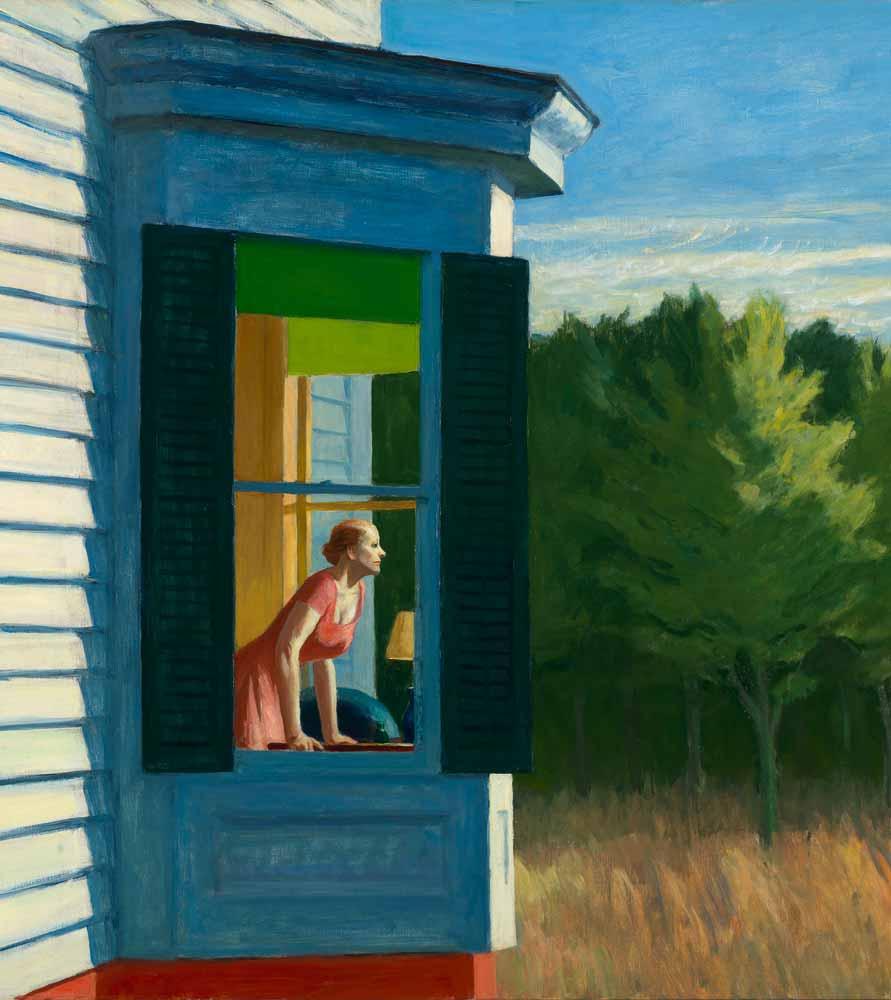

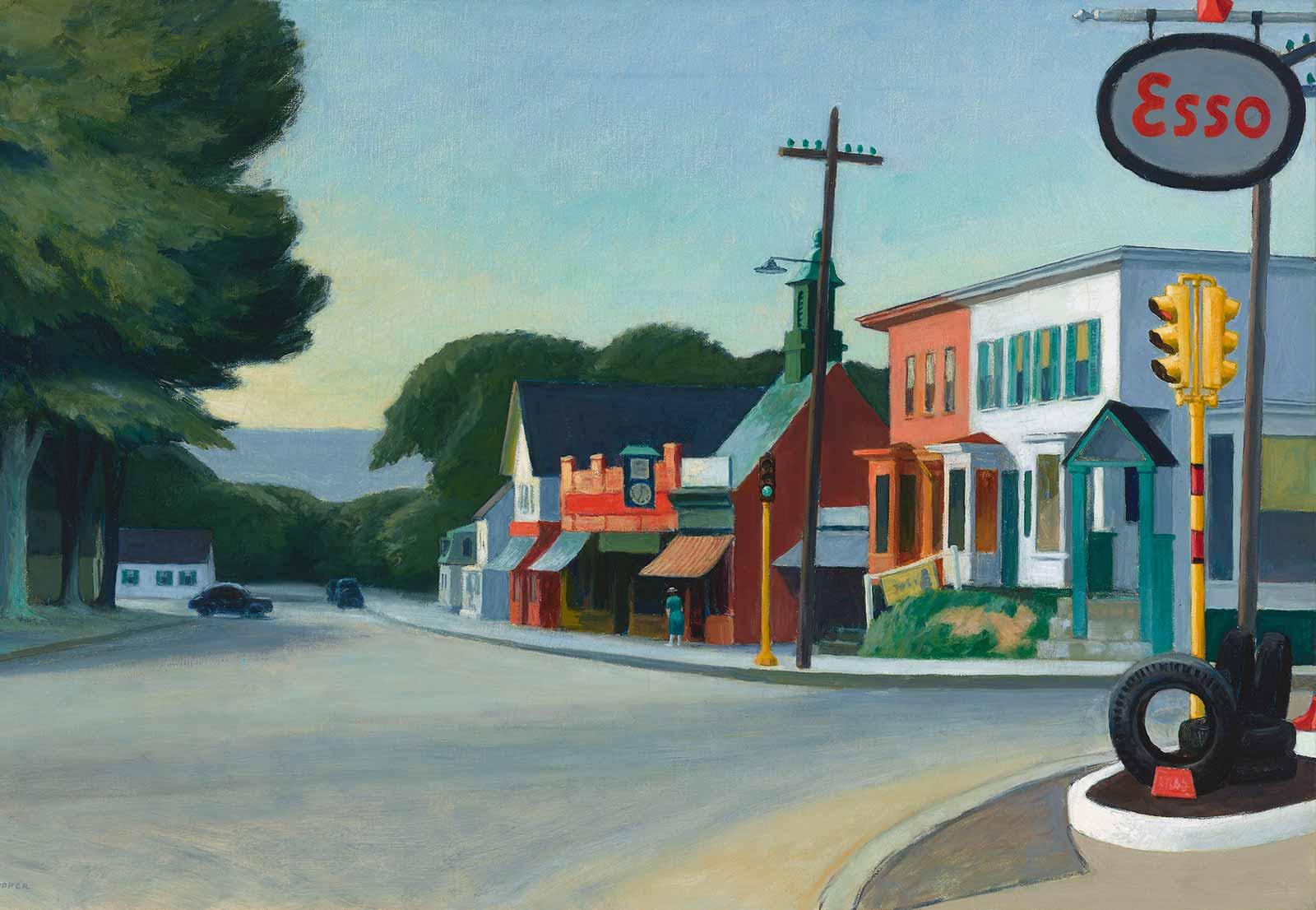

Nature, and the landscape it inhabits, are the subjects of Edward Hopper, a new exhibition at the Fondation Beyeler in Reihen, Switzerland. While Hopper may be best known for iconic city scenes like Nighthawks (1942) and Chop Suey (1929)–which sold at auction in 2018 for a record $92 million–he spent much of his life away from the hustle and bustle of New York. Beyond seasonal stays in rural Maine and Massachusetts, Hopper made many cross-country journeys and trips to Mexico by train and car, always working along the way. His paintings of empty coastlines, limitless plains, and rolling hills embody the vastness and psychological complexity of the American landscape. Hopper’s paintings show a country of endless movement, banality, and decay.