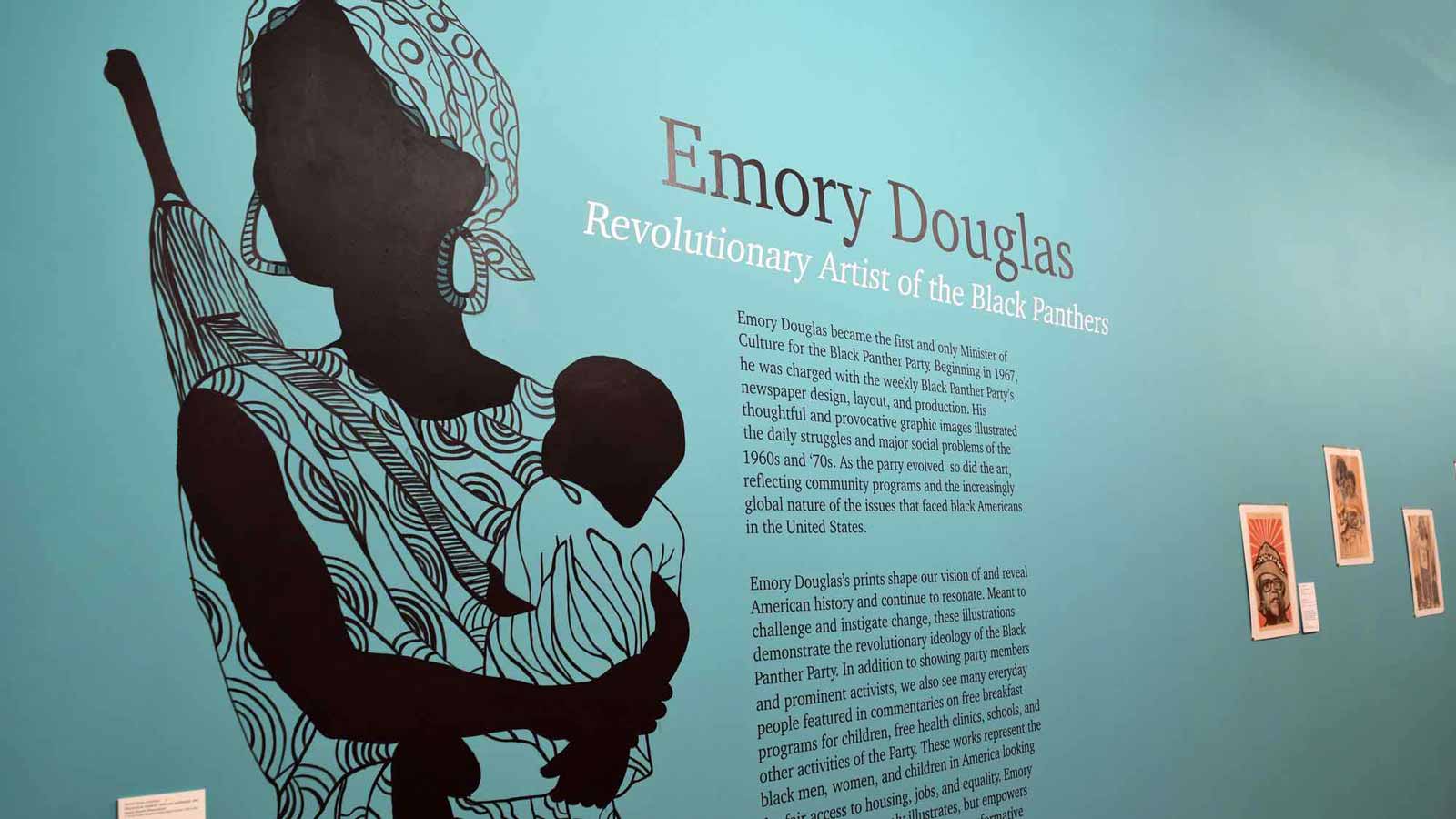

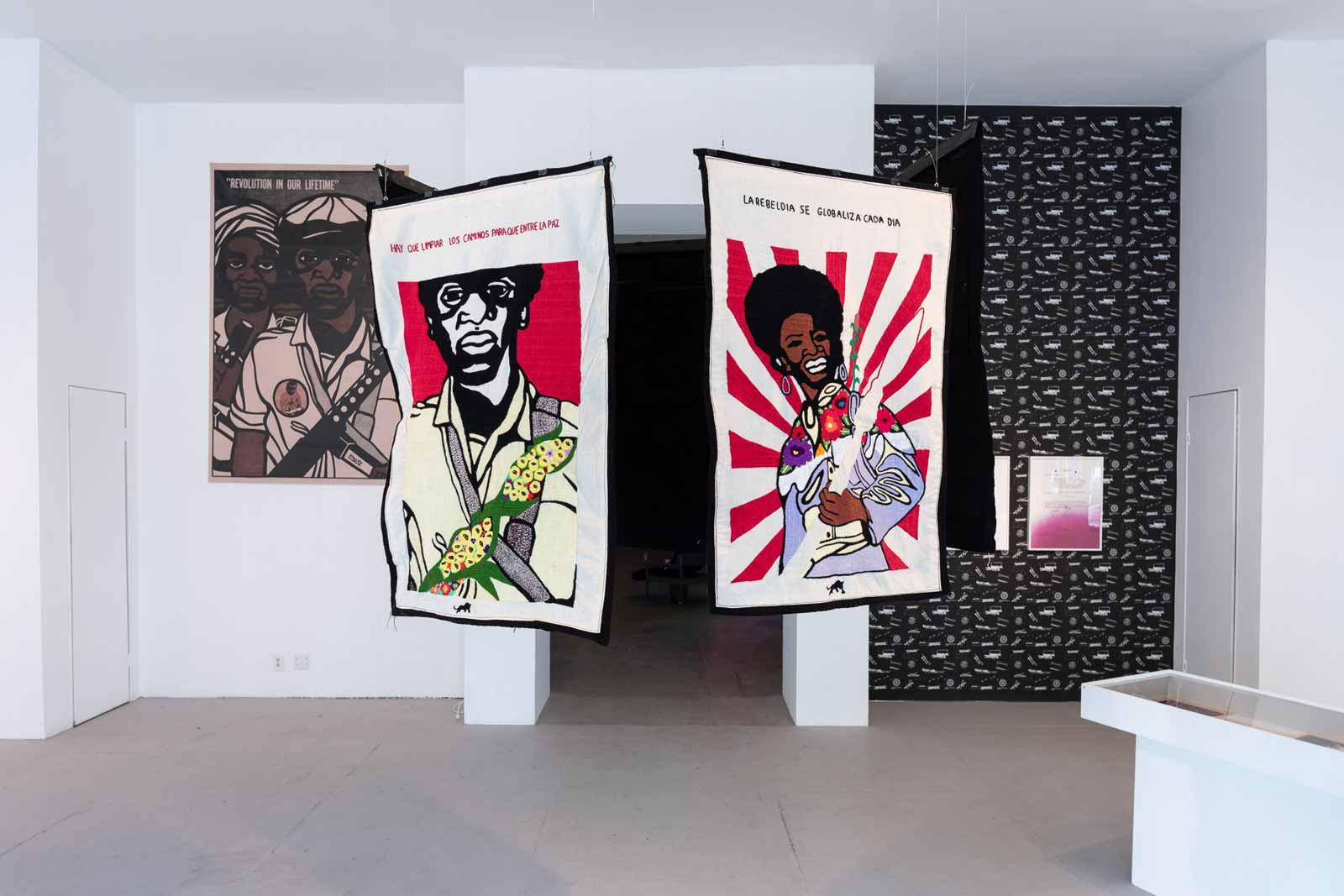

Few artists have had a greater impact on the visualization of modern politics and culture than Emory Douglas. Starting in 1967 as the first and only Minister of Culture of the Black Panther Party, his iconic images communicated the values behind the Party’s 10 Point Program. This list of social mandates sparked some real, positive change including a very successful, nationwide children’s free breakfast program. Douglas' unbroken chain of commitment to solidarity and the ideals of freedom for oppressed people around the world continues to fuel his work and has made him an inspiration to the Black Lives Matter movement today.

Born in Grand Rapids, Michigan in 1943, Emory (as he signs his work and prefers to be called) spent most of his life in the San Francisco Bay area. His early experience of being arrested led him to pursue a life as an artist whose work exposes the abuses of power within the justice system. At thirteen, Douglas was playing dice on the streets with the older kids when he was arrested for gambling and sent to a California youth detention center. Emory might have been on the path directly to prison, like many other young Black men, when, with the influence of his supportive mother, he was assigned to work in the juvenile detention center’s print shop. While there he learned the technology behind the commercial printing process, which fed his desire to pursue graphic design at San Francisco City College. His swiftly evolving political awareness led him to join the Black Students Union, formerly known as the Negro Student Association. Emory became part of a growing Black Power movement, which coincided with anti-Vietnam war sentiment and a rising feminist tide to make for an era of major cultural change not unlike our current moment.

Douglas began hanging out at the newly organized Black Panther Party headquarters in 1966. He was impressed by, “the discipline and determination of [the founders], Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, to overcome the same issues Blacks–people of color–are facing today.” Being in the right place when, in 1967, “Huey said let’s start a newspaper,” Douglas realized his design sense and drawing skills would be a valuable asset to the organization and movement. Instinctively he knew that it would take powerful imagery, combined with the right words, to effectively bring the Black Panther’s message to their community. The weekly newspaper, in print until 1980, which included images by Emory, reached its peak distribution of an estimated 139,000 to 400,000 readers a week in 1970-71.