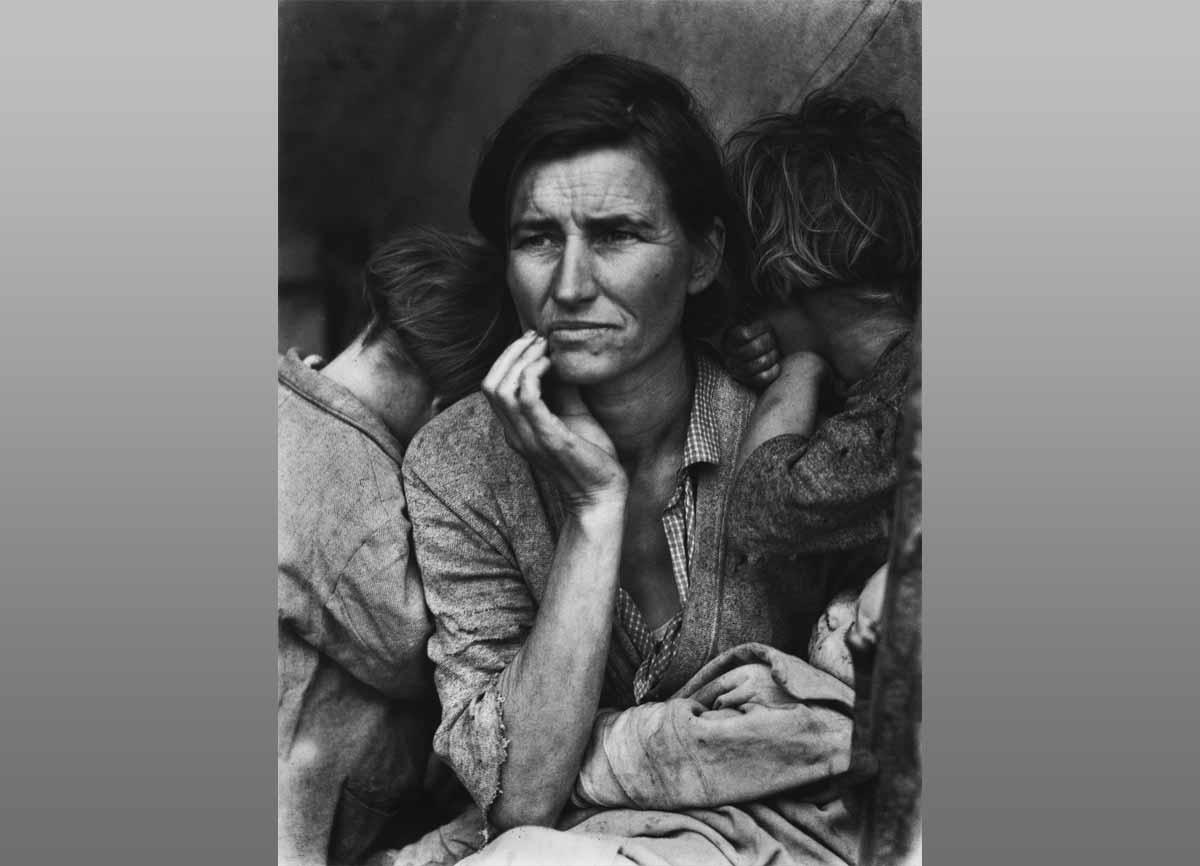

Dorothea Lange, the early 20th-century American documentary photographer, is forever synonymous with Migrant Mother (1936)–her iconic photograph of an impoverished modern-day Madonna caring for three children. “As you look at the photograph of the migrant mother, you may well say to yourself, ‘How many times have I seen this one?’” Lange herself wrote of the popular image, over two decades after she produced it for the United States government’s Farm Security Administration. “It is used and published over and over, all around the world, year after year, somewhat to my embarrassment, for I am not a ‘one-picture photographer.’”

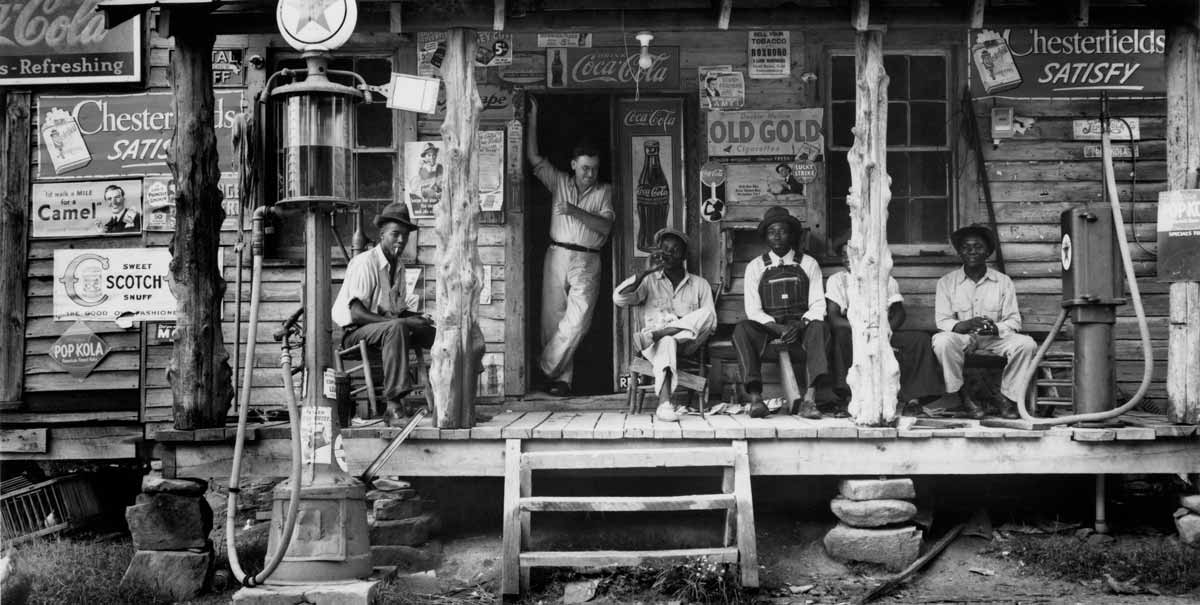

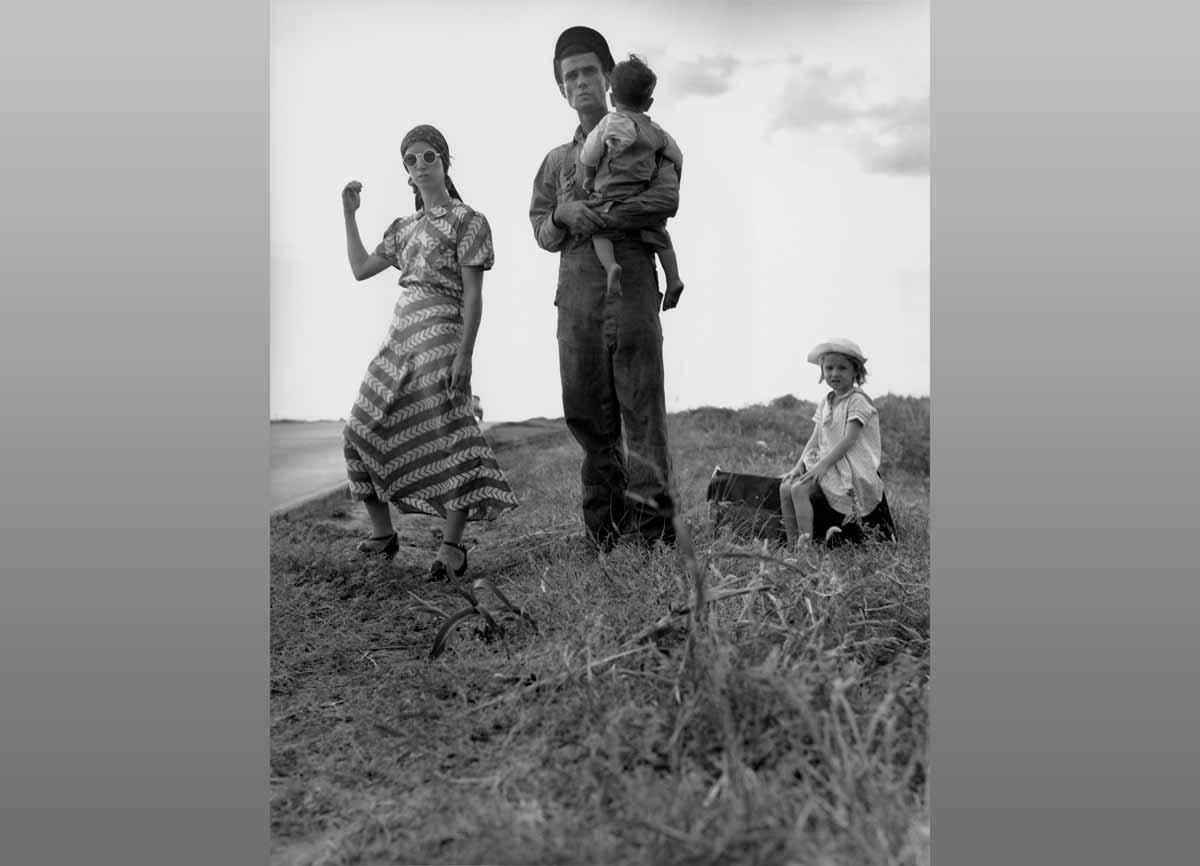

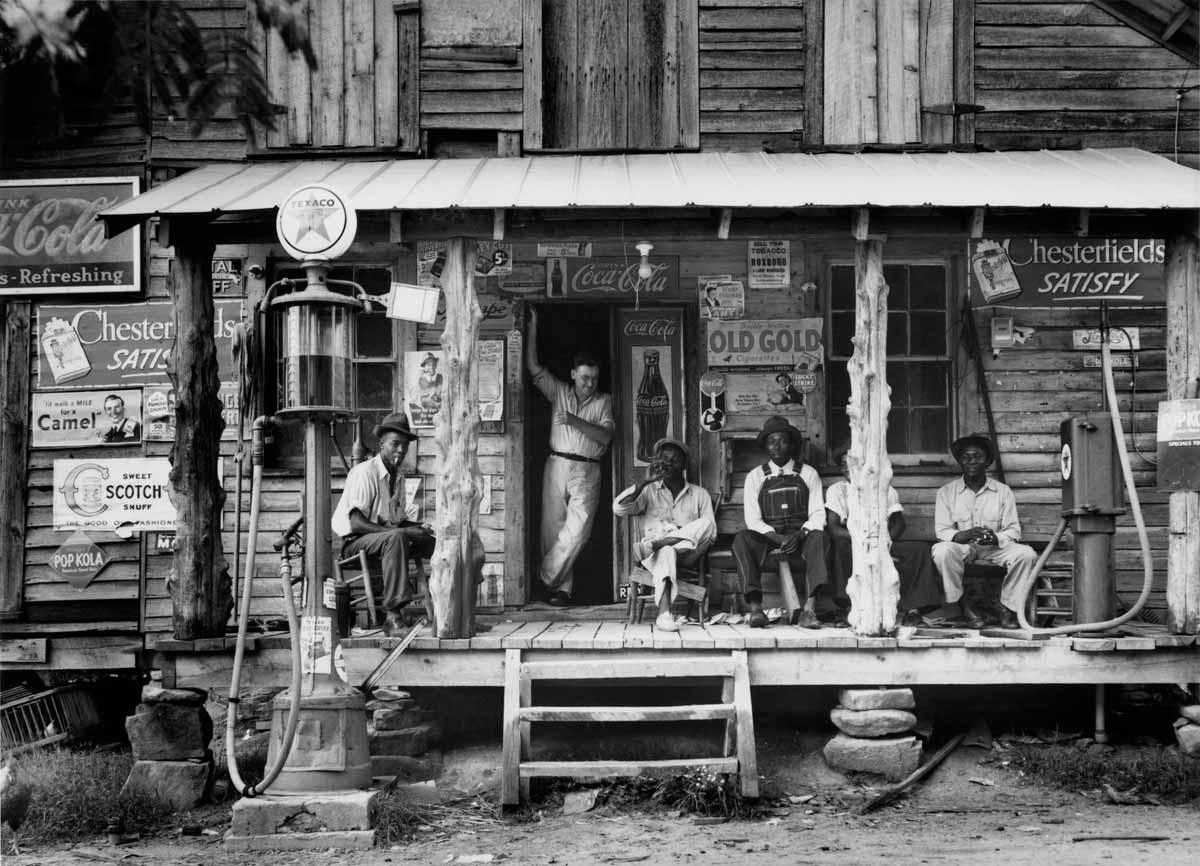

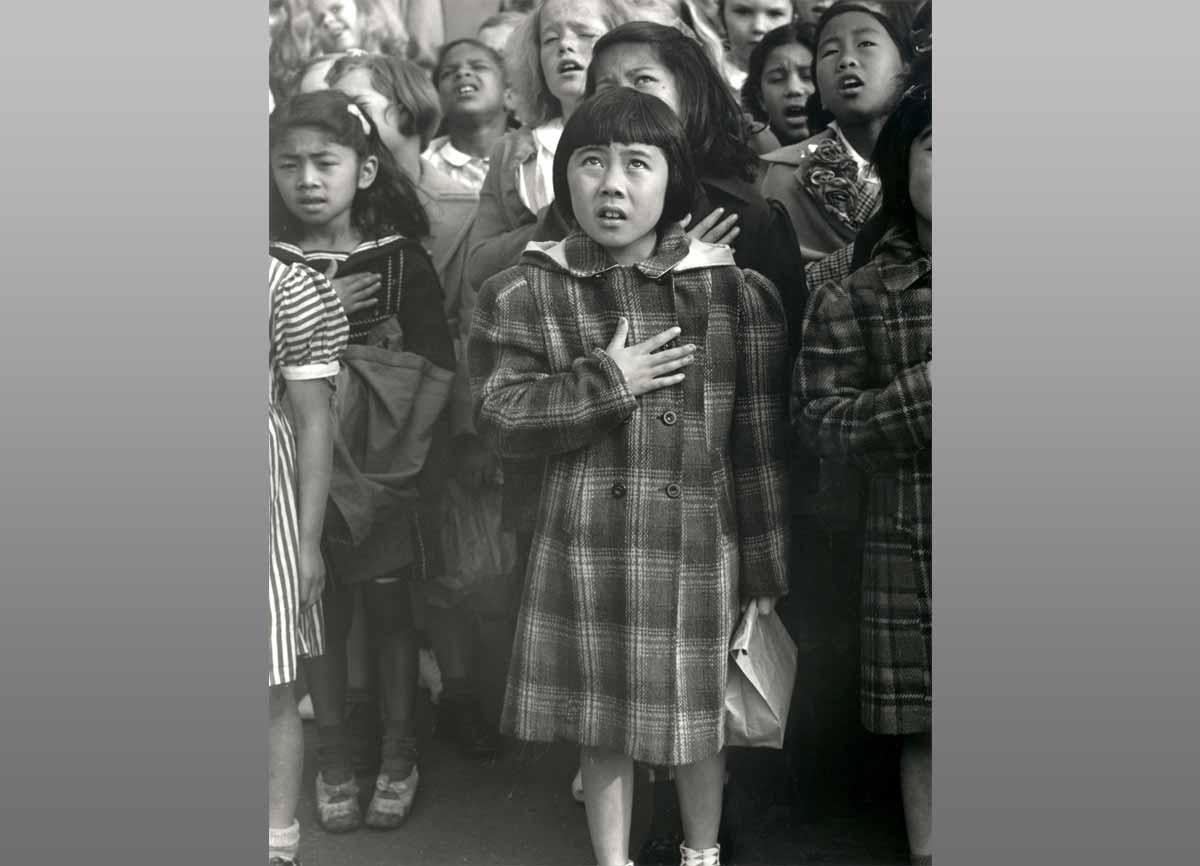

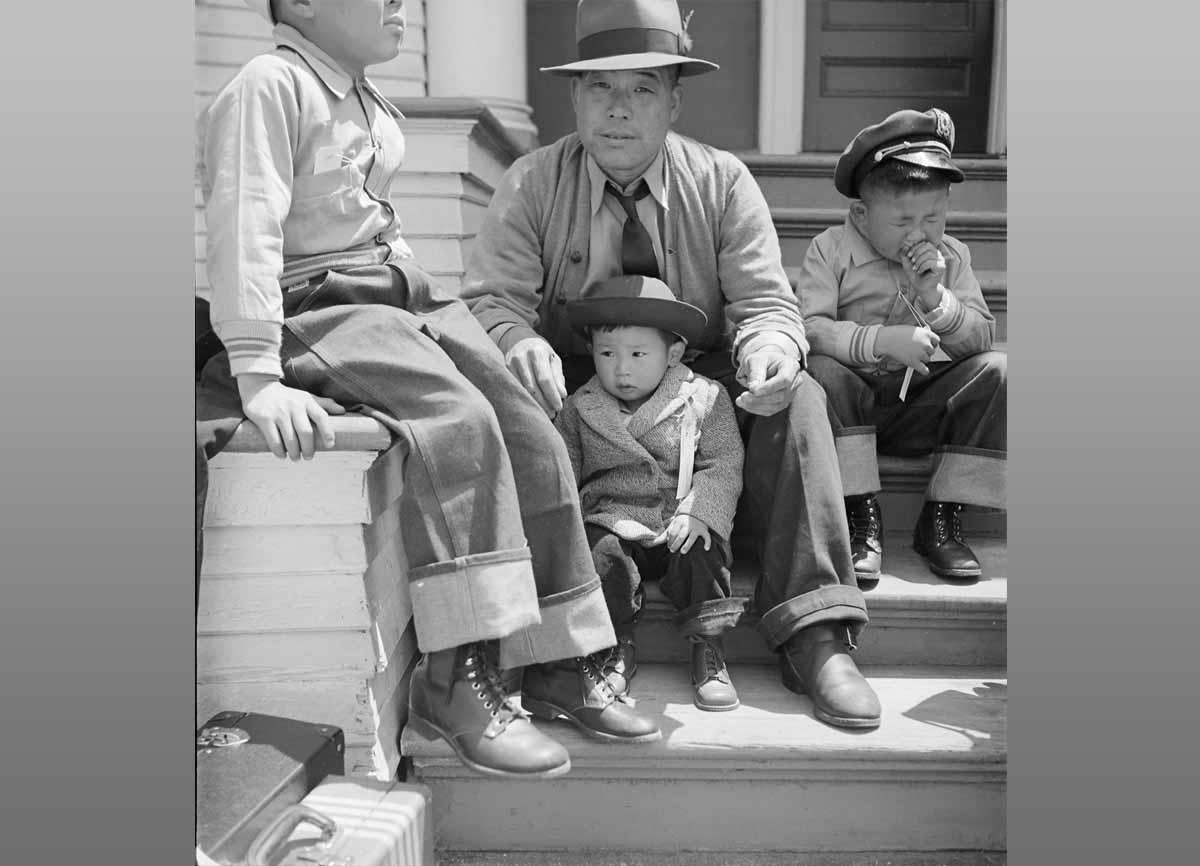

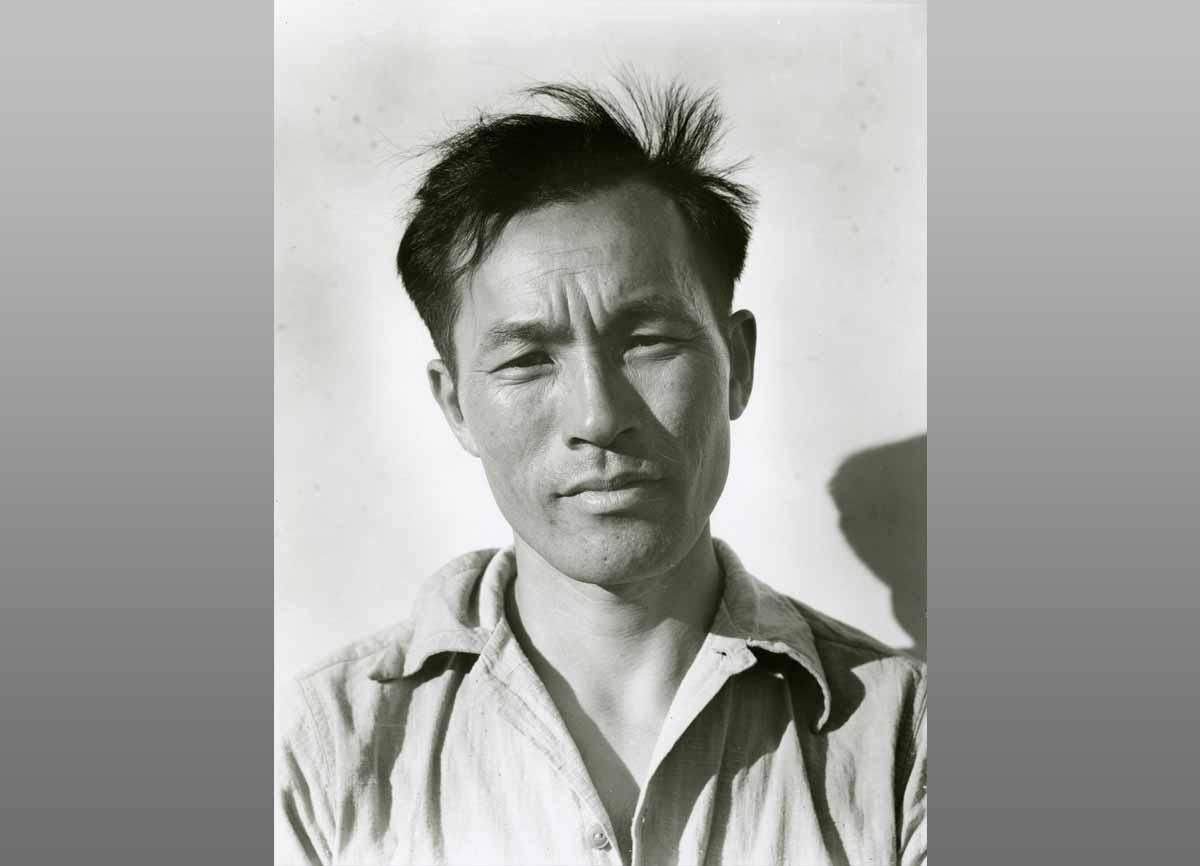

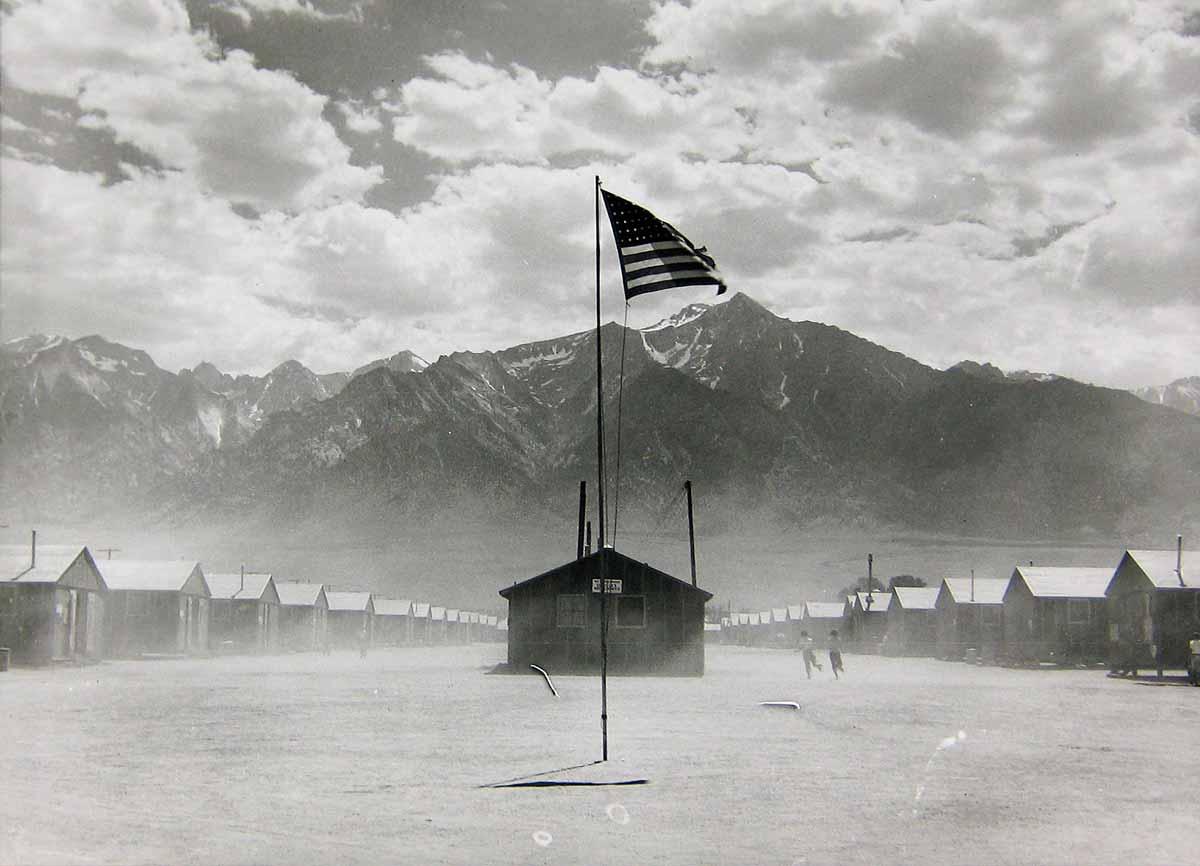

Lange left nearly 40,000 negatives and 6,000 prints in the personal archive she bequeathed to the Oakland Museum of California in 1966, and was certainly more than a one-trick pony. She photographed victims of the Great Depression, the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, the inequalities of the Jim Crow South, environmental ravages, and the Oakland criminal justice system. And recently, it is these other photographs–and she herself–that have received a burst of attention.

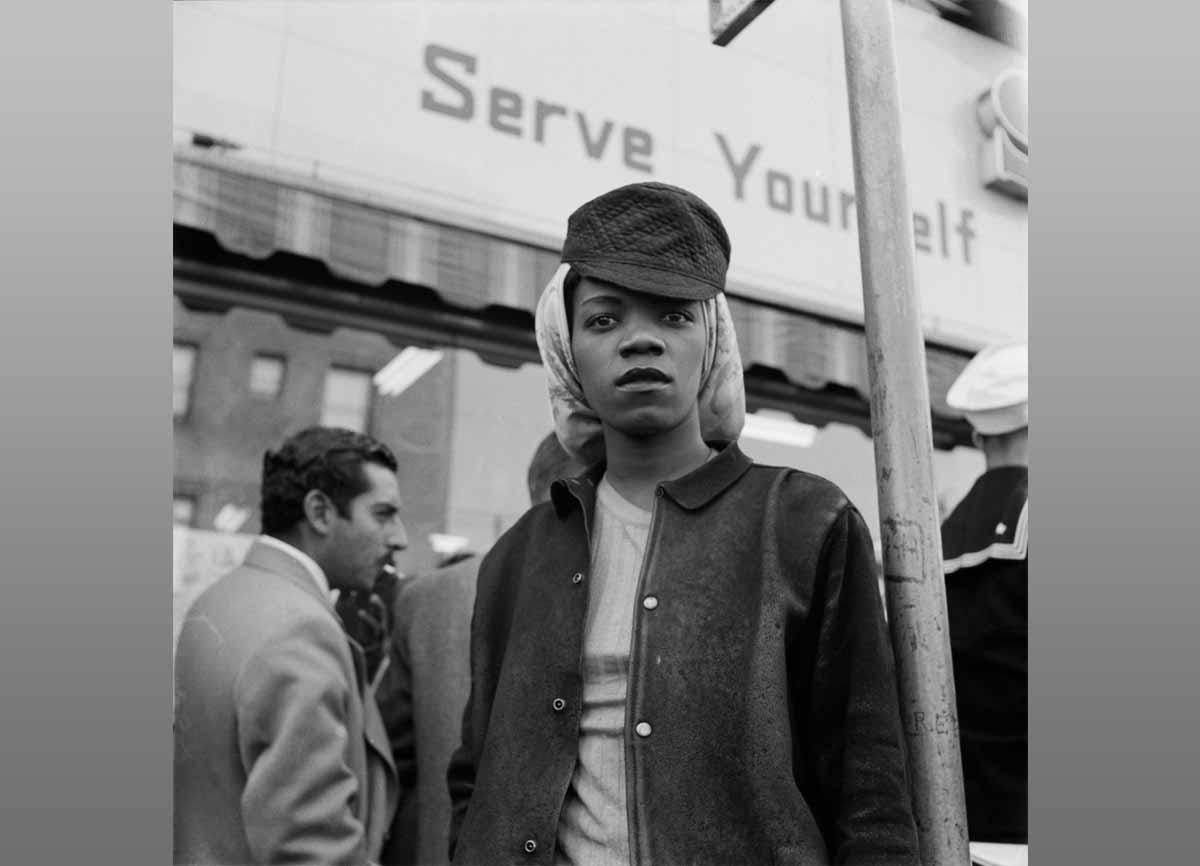

A traveling exhibition of 130 prints, Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing, began at the Oakland Museum of California in 2017 and includes some never-before-seen photographs. It has since been shown at the Barbican Art Gallery in London, Jeu de Paume in Paris, and will open this month at the Frist Art Museum in Tennessee. A recently released historical fiction novel, Learning to See (Harper Collins, 2019), has also brought Lange into the limelight, flipping the lens on the life of the woman behind the camera.

“I've seen increased interest in Lange,” Drew Heath Johnson, curator of photography and visual culture at the Oakland Museum of California, told Art & Object. “Her photographs are shockingly relevant today, and especially powerful thanks to the profound empathy of her approach.”