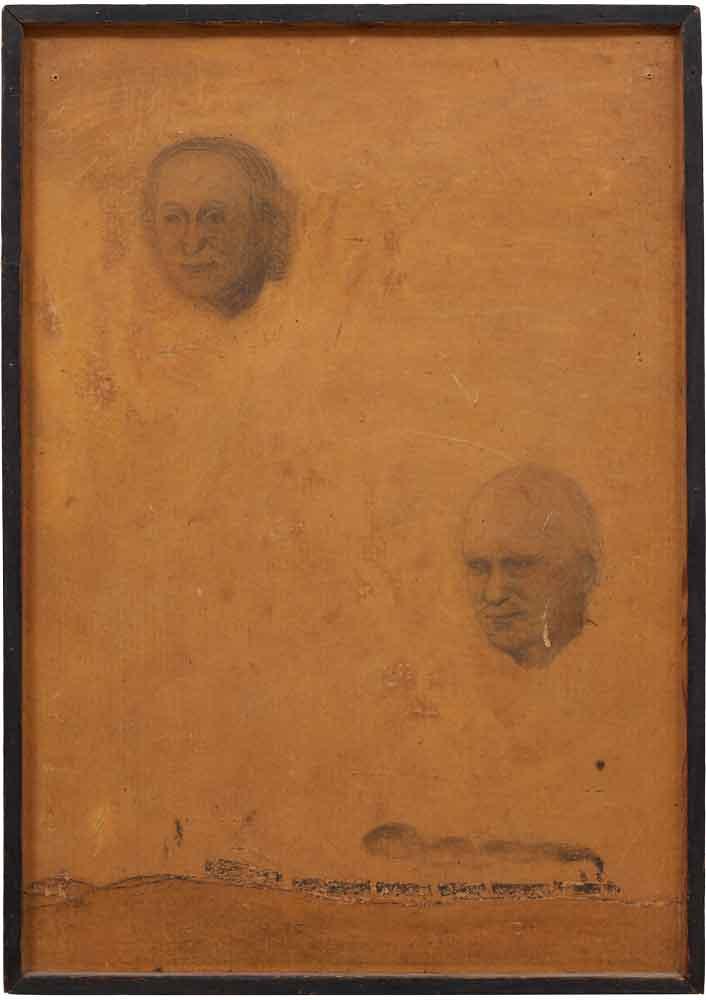

To understand some of this inherent magic, Gingeras turned to theory by Bruno Bettelheim, a child psychologist who wrote about the relationship between trauma and fairy-tale narratives. Rosenstein processed her experience through writing fables and painting her philosophical, slightly fantastical works. She repeatedly depicted the same subjects, rendering her parents’ faces with almost-photographic detail. Rather than portraying the events realistically, Gingeras suggests that Rosenstein instead “transforms this primal scene into disconcerting, often magically tinged dreamscapes.”

Of course, there is a certain difficulty in describing the relationship between trauma and art; in writing about Rosenstein, Gingeras had to navigate around a whole arsenal of tropes relating to Rosenstein’s identity. In the catalogue and the exhibition, Gingeras carefully skirts the myth of the sui generis artist—the artist plucked from obscurity with a defined practice and style. Beyond that, Gingeras insists, “I was very careful to say in my essay that she would not embrace the label of feminism.” Like other artists in the period that prioritized communism over feminism, “she had a quite humanist approach. Her work was about addressing the perseverance of the human spirit.”

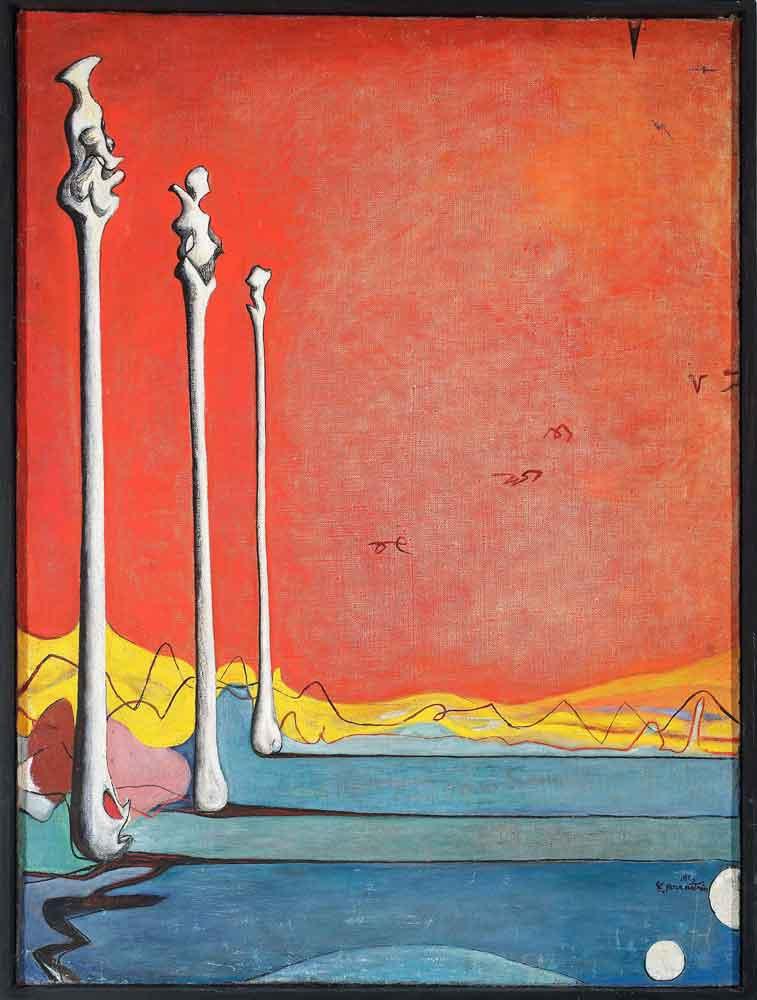

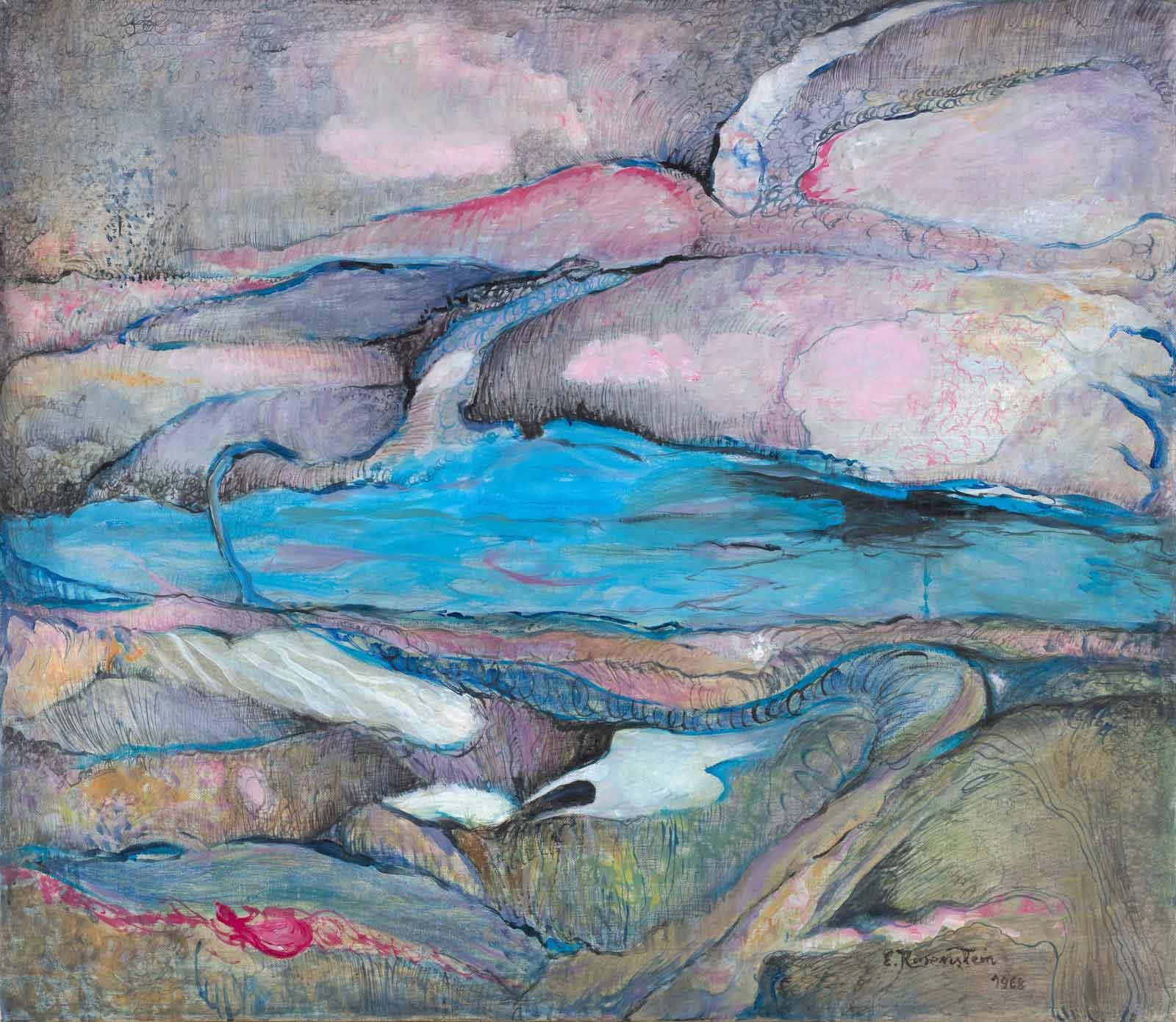

The perseverance of the human spirit comes up against the inadequacy of memorialization. During our interview, Gingeras adds, “I think a lot of her work, even the poetry, is really about the impossibility of memorial in monuments, but the centrality of memory. The landscape trope is a perfect vehicle for dealing with that.” Rosenstein’s biomorphic, slightly alchemical landscapes are illustrative and colorful and full of wonder, like a fairy tale. But landscapes can also conceal, as they grow over and evolve beyond the unthinkable horrors that took place there. Rosenstein questions the silences and invisibilities of landscapes, as much as what she actually depicts.

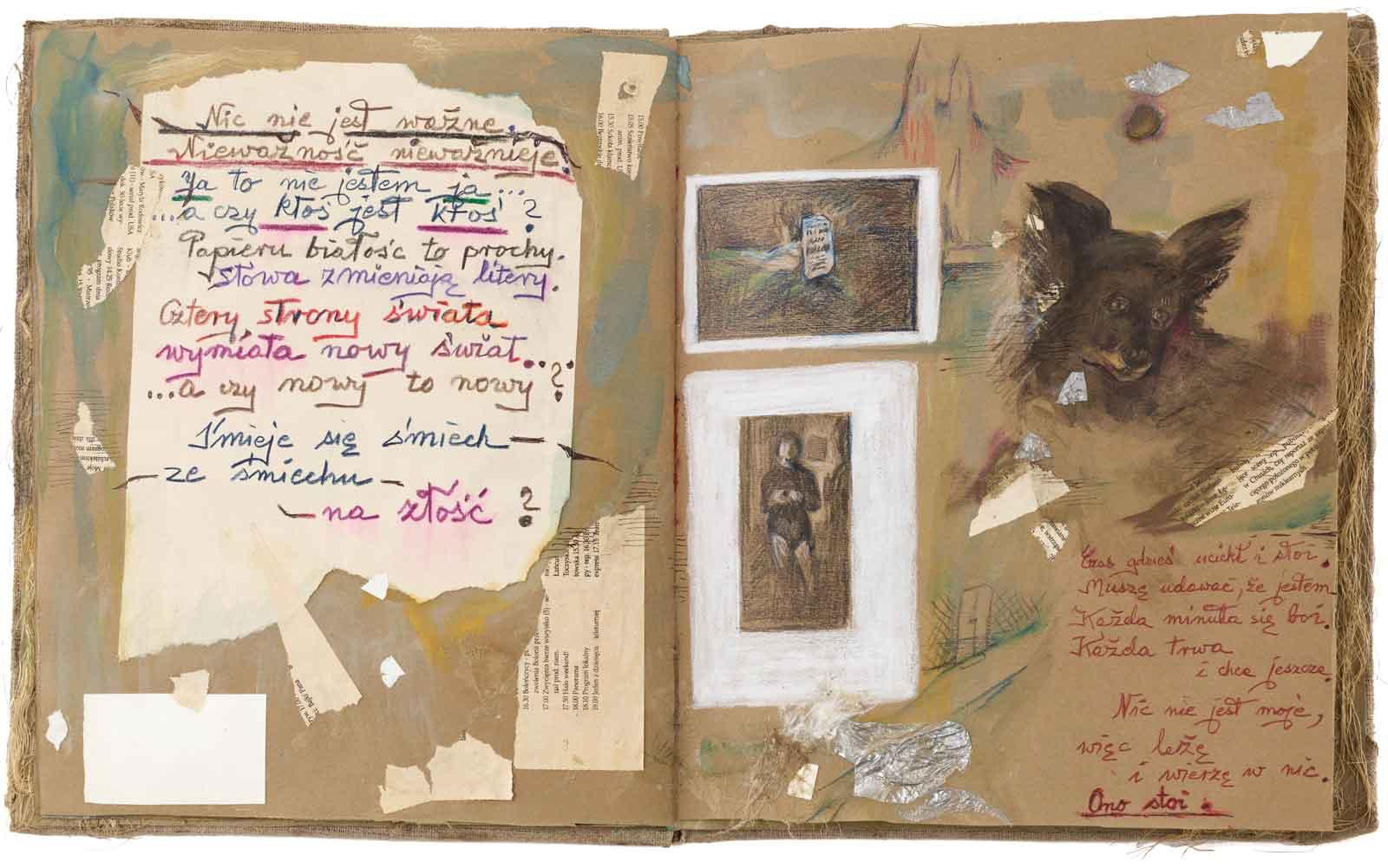

In describing the 1985 Holocaust documentary, Shoah, critic Richard Brody wrote that the film “bears witness to the bearing of witness.” Something similar happens in Rosenstein’s work from the postwar period. She processes her own remembrances by both reciting moments that were intensely personal to her and portraying them from a controlled, self-motivated distance. Her work is testimony. As both eyewitness and artist, her work, as Gingeras notes, corrects “the discrepancy left between the official monument, human memory, and the march of time.”

Find Out More