Deep purple stage curtains drawn back in swags at either side of the entrance to the Shelburne Museum’s 2018 exhibition Puppets: World on a String, inviting the viewer to enter a world behind the scenes where everyday life is transformed into something magical. Curator Carolyn Bauer managed to distill the 3,000+ year history of the genre-busting art form of puppetry into a masterful showcase organized thematically in three sections: Otherworldly: Fairytales and Fantasy; Dancing Shadows, Moving Silhouettes; and Behind the Curtain: Everyday Life.

While known for its extensive collection of objects, including a vast, century-spanning doll collection, the Shelburne Museum has a surprisingly small group of twenty puppets, necessitating loans from outside institutions and individual artists for this exhibition. Centered in a tall, glass case serving as the stage between the entryway curtains, Queen of the Night on a Cloud (1986) and Prince Tomino (1986), two spectacular examples of marionettes by Frank Ballard (1929-2010) from a performance of Mozart’s fantastical opera The Magic Flute (1791) were on loan from the Ballard Institute and Museum of Puppetry at the University of Connecticut. These ornately costumed, richly detailed, wood, neoprene and fabric figures illustrate their power to inspire our desire to covet them as beautiful objects, and to lead us into imaginary realms of heroic deeds and deceptive villains. The mechanism of strings used to bring these characters to life was also artfully displayed to reveal the technology and the reality behind the magic. Frank Ballard established the first degree-granting curriculum in puppet arts at the University of Connecticut, still one of the field’s most respected programs.

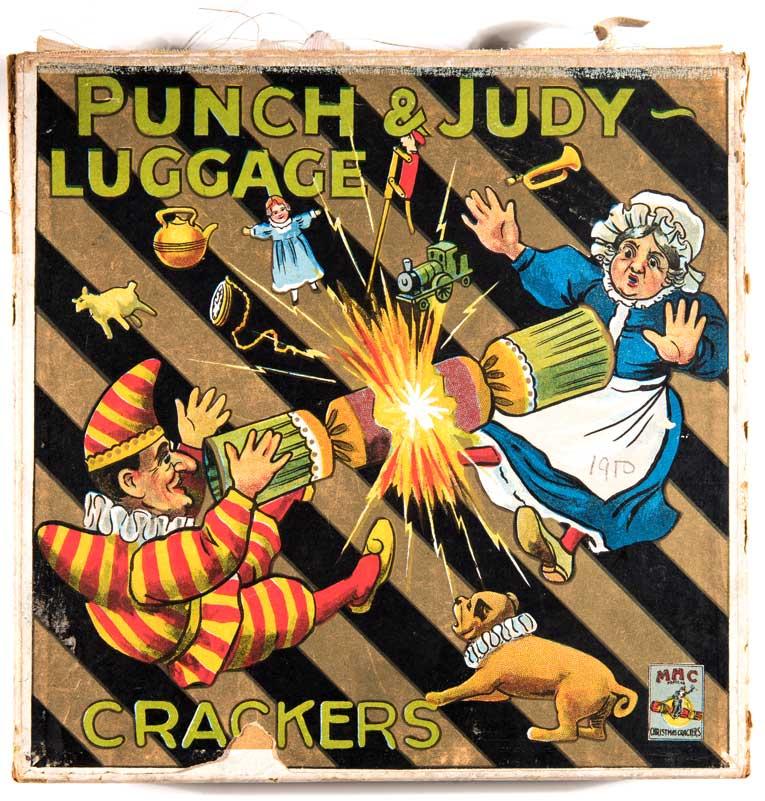

No exhibition of puppetry can be complete without Punch and Judy, an internationally recognized iconic, centuries-old, darkly comedic duo first adapted from the 17th-century Italian puppet show Pulcinella. The two wood, cotton, and paint glove puppets shown here date from the late 18th century. Along with Punch & Judy Luggage Crackers, a 1910 chromolithograph and Punch, a large 19th-century wood and paint cigar-store figure, these objects demonstrate the influence of Punch and Judy characters in the early days of advertising. They required considerable restoration work and were the only items drawn from the museum's own collection