The Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico claims the world’s largest collection of folk art. The museum’s website displays 130,000-plus objects from more than 100 countries. Online, an alphabetical listing indicates the depth of all the forms making up the category of folk art. The digital catalog begins with the letter “A” for amulets, angels, anklets, apothecary jars, aprons, ashtrays, and axes on to “B” for baby shoes, bags, basins, baskets, beads, belts, birdcages, bowls, and so on through the alphabet.

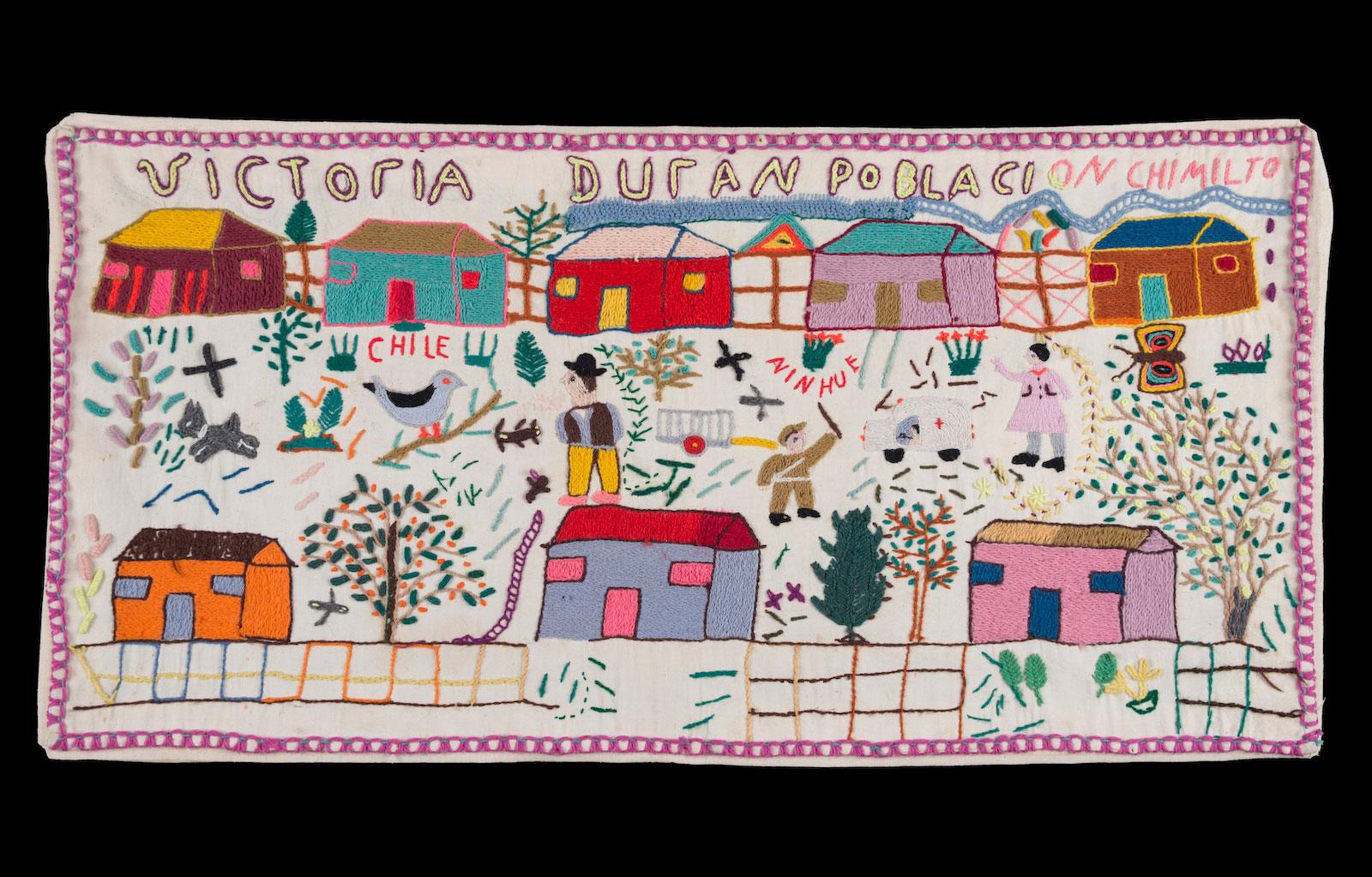

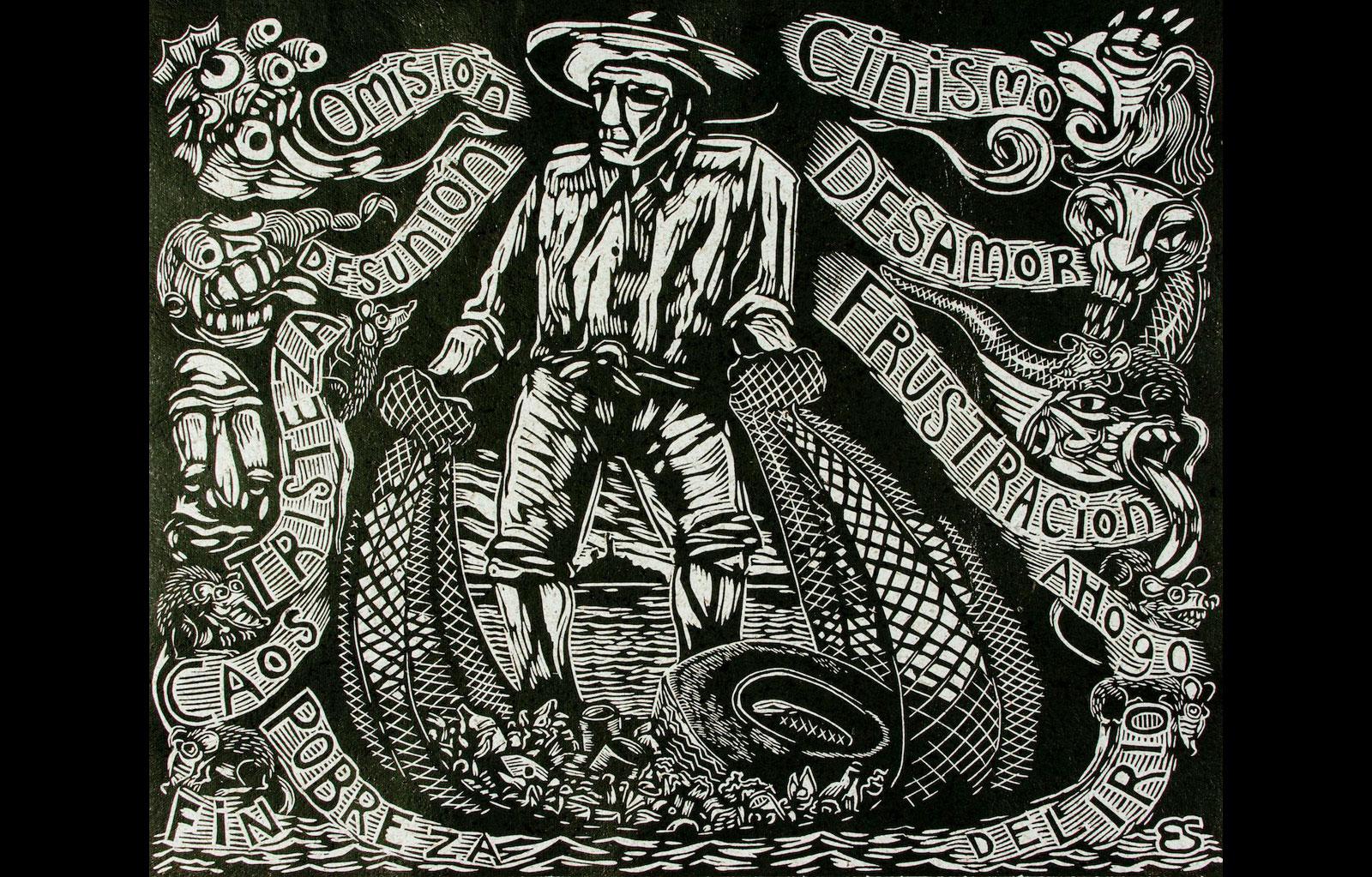

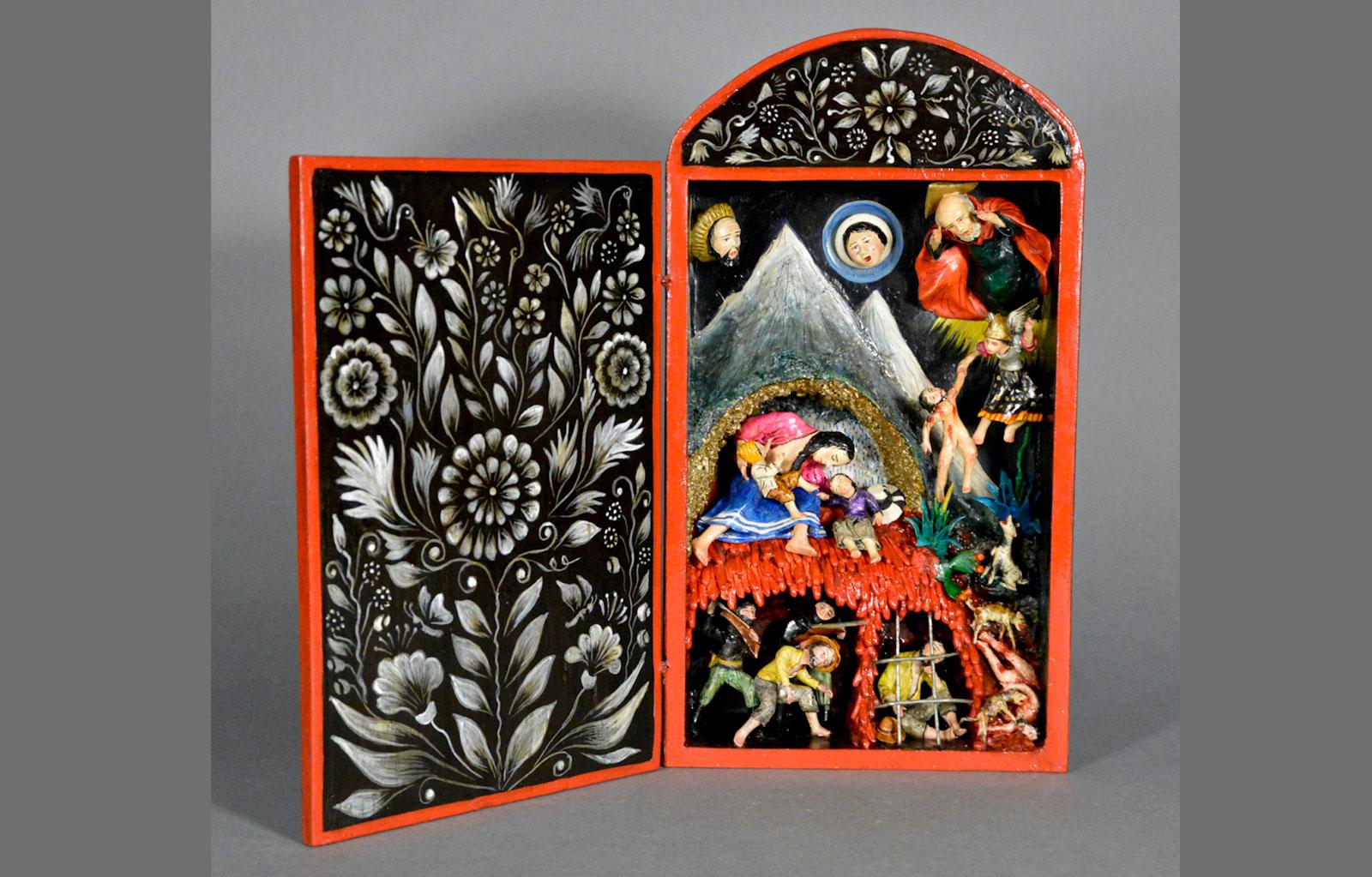

The museum’s collection includes textiles, paintings, pottery, sculpture, and every other form of fine art, as well as kinetic toys, musical instruments, and sundry decorative or utilitarian objects from everyday life or high ceremony. And the Museum of International Folk Art collection demonstrates clearly that every culture creates folk art.

“No matter what your political views are or which society you come from, there is folk art,” says Khristaan Villela, the folk art museum’s executive director since 2016.