In a 1931 lecture, Frank Lloyd Wright said, “I have been black and blue in some spot, somewhere, almost all my life from too intimate contacts with my own furniture.”

Consequently, the architect-designed furnishings are fully integrated into his interiors. Less likely to bruise and more apt to appease his overarching aesthetics, Wright’s furnishings are as admirable as his buildings.

After moving into their Frank Lloyd Wright-designed home in 1960, Dr. Paul Olfelt and his wife Helen bought only a few pieces of furniture.

“Other than beds and nightstands, I think the only furniture my parents ever purchased were two swivel chairs in the living room,” said John Olfelt, an architect for 3M. “In the overall environment of the space, Wright’s furniture is an integral part.”

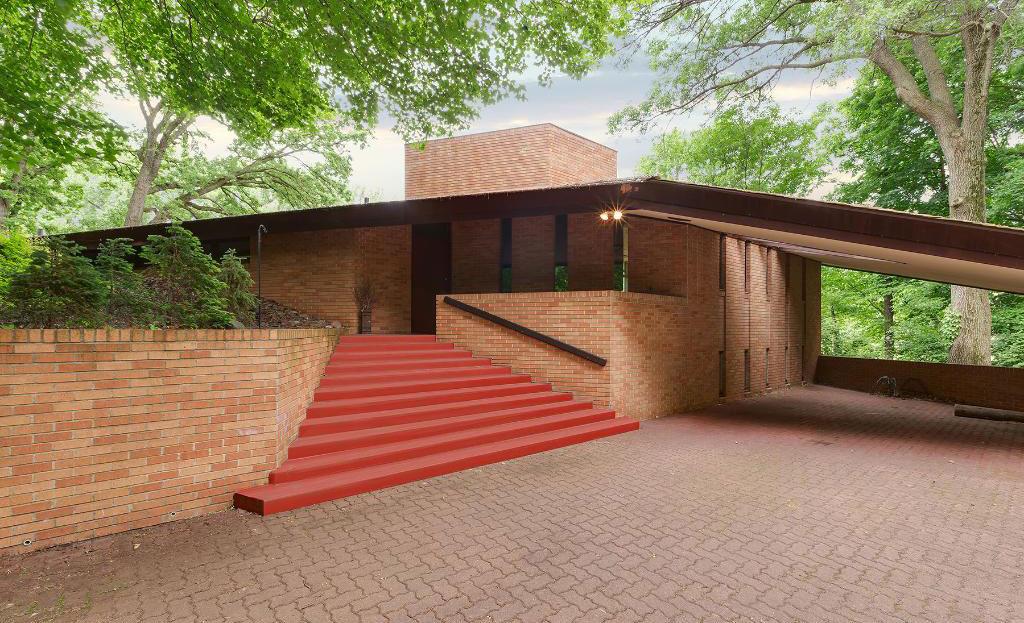

The architectural world celebrated the 150th anniversary of Wright’s birth in 2017, meanwhile, the Olfelt House, located near downtown Minneapolis, was for sale, listed at $1.3 million through Coldwell Banker Burnet's Berg Larsen Group.

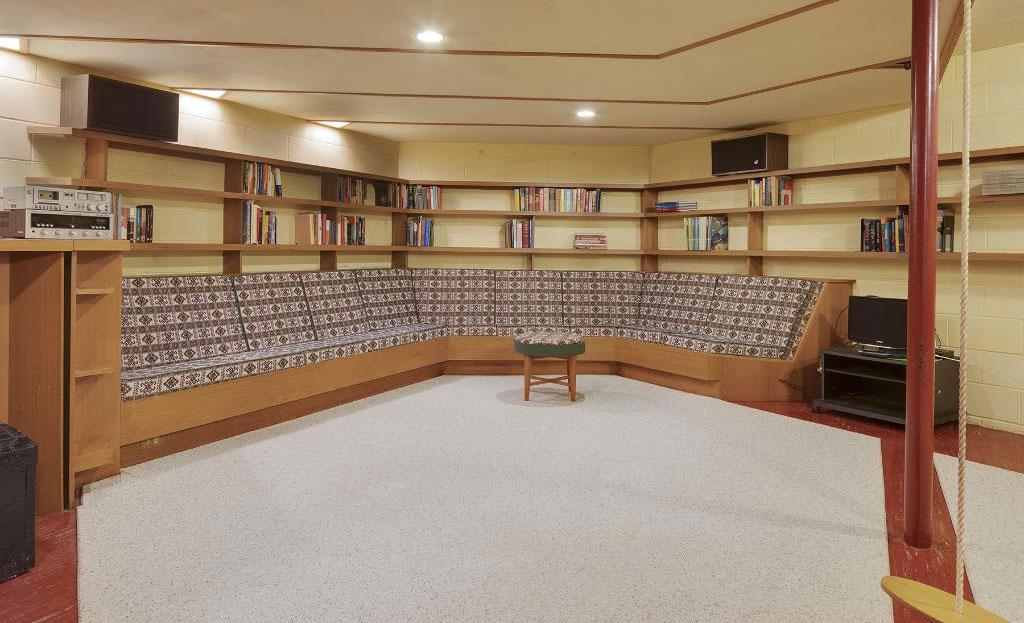

In signature Wright style, the uncluttered residence features both built-in and freestanding furnishings that contribute to the artistic unity of the home.

“Wright designed all the built-in furnishings, which was most everything: desks and their drawers in all the bedrooms and living room, chairs, lighting, book shelves, dressers (in closets) and the dining room tables, chairs, dining room pendant, living room chairs, an integrated sofa and stools, and kitchen table and stools.”

Olfelt admired both the form and the function of Wright’s furnishings in his parents’ home.

“All were reasonably comfortable, but with straight backs, the chairs made you sit up straighter. The chairs had 90-degree backs and therefore were more formal,” he said.

“The long living room sofa was originally designed to have a back 90 degrees off the seat, but was changed to have about a five to ten degree offset from the 90, to be more comfortable. This change was done through the Taliesin apprentice and contractor.”

In an article published in 1969 in Northwest Architect, Olfelt’s late father, a radiologist, wrote, “We hoped for a refuge from the world for part of our day, a place where we could enjoy nature and the beauty of man’s creativeness in harmony with nature. We wanted a home that by virtue of its character would help us and our children be dissatisfied with the ordinary.”

The house so powerfully influenced his son that in college John Olfelt switched majors from pre-med to studio arts and architecture.

“I think any good design has some aspect of being ‘dissatisfied with the ordinary.’ Design should challenge our established perceptions and expand our thinking,” said Olfelt, who was three years old when his family moved into the house.

“As I got older, I began to appreciate how everything was integrated, from floor to ceiling, the lighting and the furniture. Wright was consistent, ” Olfelt said.

Wright’s furnishings designed specifically for the Olfelt House reflect the house’s blueprints. Just as his cantilevered sofas and chairs mirror the terraces of Fallingwater, the Olfelt House includes geometrical influences from the residence’s footprint.

“The home was designed on a parallelogram with a 60 and 120 degree grid,” said Olfelt. “That means that nearly all the walls fell on that grid, as well as the furniture. Even the desk drawer pulled out at an angle following this grid—not 90 degrees, as expected. The dining room table got an extension from an adjacent table that is integrated into the bookshelves.”

Asked whether he had a favorite place in the home to sit, Olfelt said, “Definitely. The living room: a beautiful space with warmth, sunlight and views. A lot of daydreaming could—and did—occur there.”