Before there was Normandy in northern France, there was Roman Gaul, and remains of this centuries-old society still rest under the earth. On a spring day in 1830, a farmer named Prosper Taurin was plowing his field near the village of Berthouville, and his blade hit something hard. Beneath what would be identified as a Roman tile was a cache of glittering objects. He used his hoe to pull them from a brick-lined vault, finding fifty pounds of silver statuettes, bowls, jugs, and pitchers decorated with centaurs and gods.

Now known as the Berthouville Treasure, this serendipitous find of ninety objects dating from the first to third centuries CE is the biggest and best preserved ancient silver hoard ever found. Today it’s part of the Department of Coins, Medals, and Antiques in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BnF) in Paris. In 2010, it departed France for the first time, arriving at the J. Paul Getty Museum’s Antiquities Conservation for a multi-year conservation and research project. Since 2014, it’s been on tour in the United States and Europe.

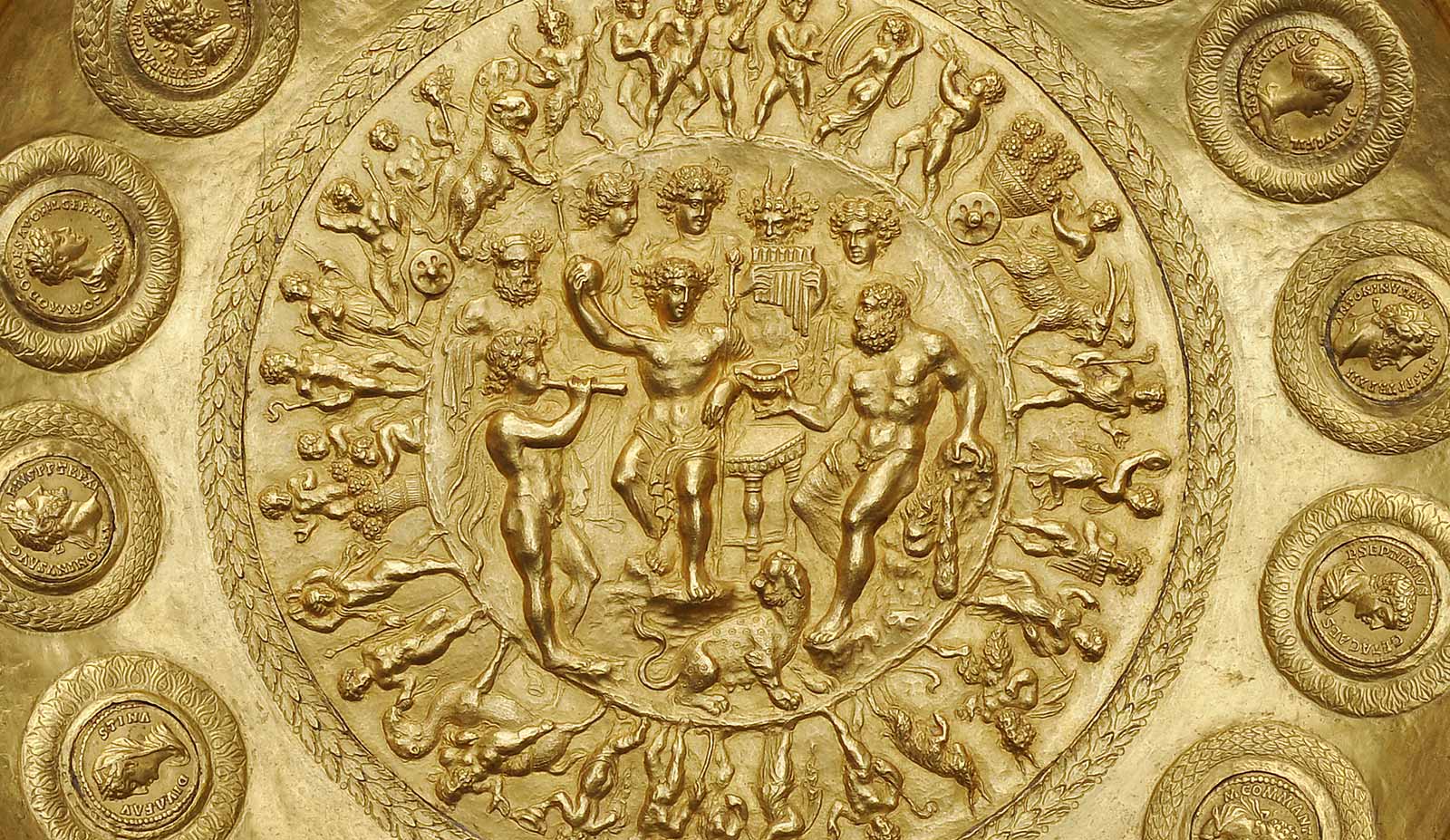

The Berthouville Treasure’s final stop before returning to Paris was the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW) in New York, where its significance as evidence of cross-cultural exchange was highlighted in Devotion and Decadence: The Berthouville Treasure and Roman Luxury from the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in 2018. ISAW was established in 2006 at New York University to engage with research and education on cultural interconnections in the ancient world. While one gallery at ISAW concentrated on the Berthouville Treasure, a second had over seventy examples of Roman luxury objects from the BnF, such as gems, coins, jewelry, marble, an incredibly fine mosaic from Hadrian’s villa in Tivoli, and Late Antique missoria, or large silver platters.

“For us, this exhibition is not only showing that there were these spectacular works of art, with lavish materials and materials that gesture at the breadth of the Roman Empire and the power of the Empire,” said Clare Fitzgerald, ISAW’s associate director for exhibitions and gallery curator. “We’re focusing on what this tells us about the way in which culture changes and responds to that which it encounters.”