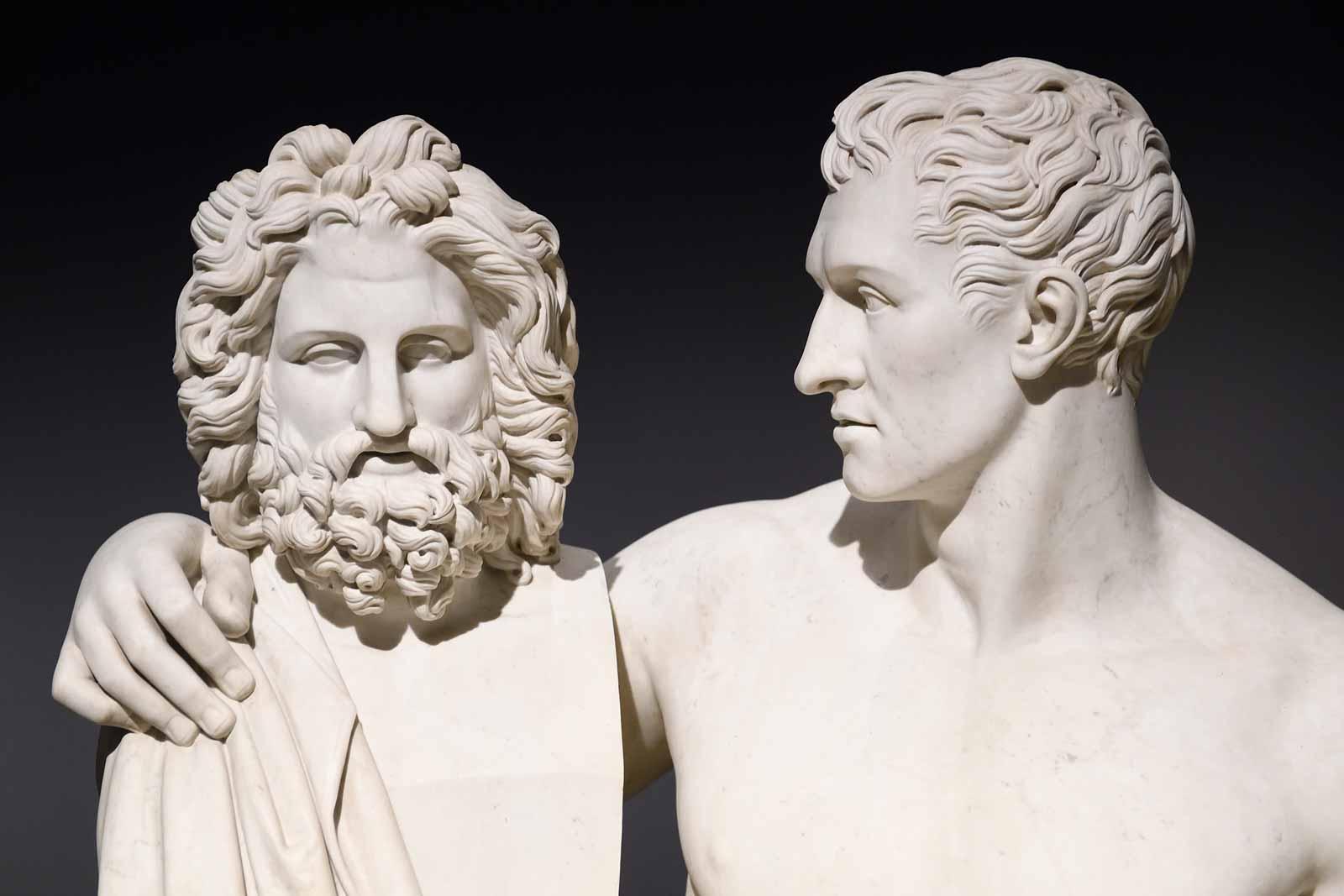

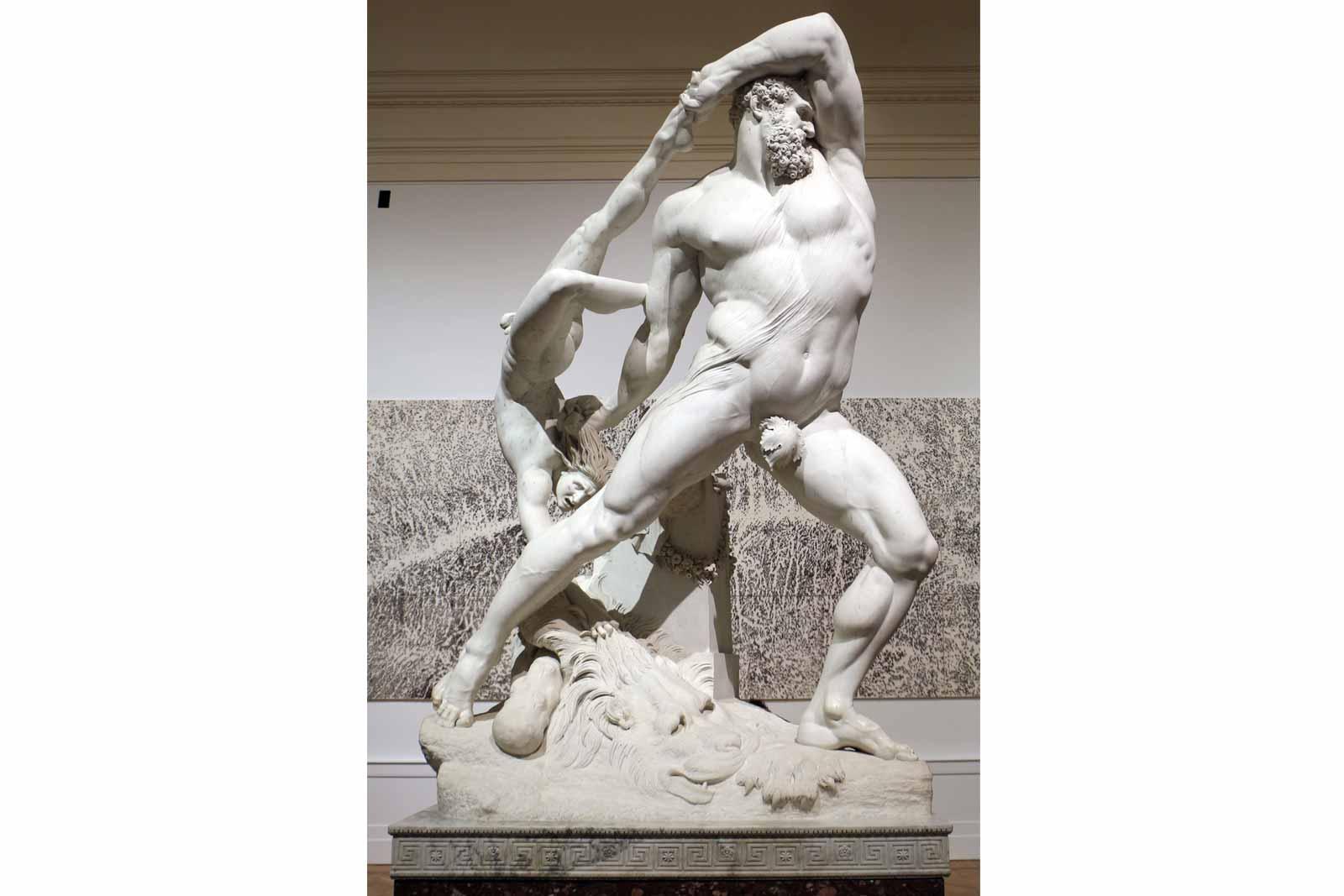

Upon admiring Antonio Canova’s most famous statues, which include Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss (1787), Perseus with the Head of Medusa (1804-6), and Dancer with Her Hands on her Hips (1805-12), we are primarily struck by the pristine beauty and harmony they convey. Neoclassicism, the artistic and cultural movement he played a key role in, is known for reinstating the purity and harmony of classical antiquity after the overly decorated works with contorted lines of actions in the baroque and the Rococo era. It was the time of the rediscovery of Pompeii and Herculaneum, and, overall, Neoclassicism was a revival of the styles of classical antiquity. Yet, underneath the veneer of classical beauty and harmony, Canova was a great innovator who was learning from history while modernizing sculpture.

It all started in Rome in the late 18th century. Despite the burgeoning presence of other art cities worldwide, such as London and Paris, Rome still detained great importance for an artist’s education. “At the peak of the Neoclassical period, having an artist understand and interpret the masterpieces of antiquity was paramount,” said Fernando Mazzocca, co-curator of the recent exhibition Canova and Thorvaldsen: The Birth of Modern Sculpture at the Gallerie d’Italia, Piazza Scala, Milan. As luck would have it, throughout the 18th century, archaeological treasures kept surfacing in the area, museums were being established, “Rome was Europe’s open-air or immersive art school,” said Mazzocca. “People from all over the world, including America, visited Rome for study purposes.” And while they still paid some attention to Renaissance and Baroque-era sculptures, it was not comparable to the attention devoted to antiquity.

In this milieu, Antonio Canova (1757-1822) is credited with reviving sculpture as an artistic genre. “After the great sculpture production of the baroque era, it came to a point, in Rome, where interest in excavations and found archaeological artifacts was detrimental to actual artistic production,” said Mazzocca.