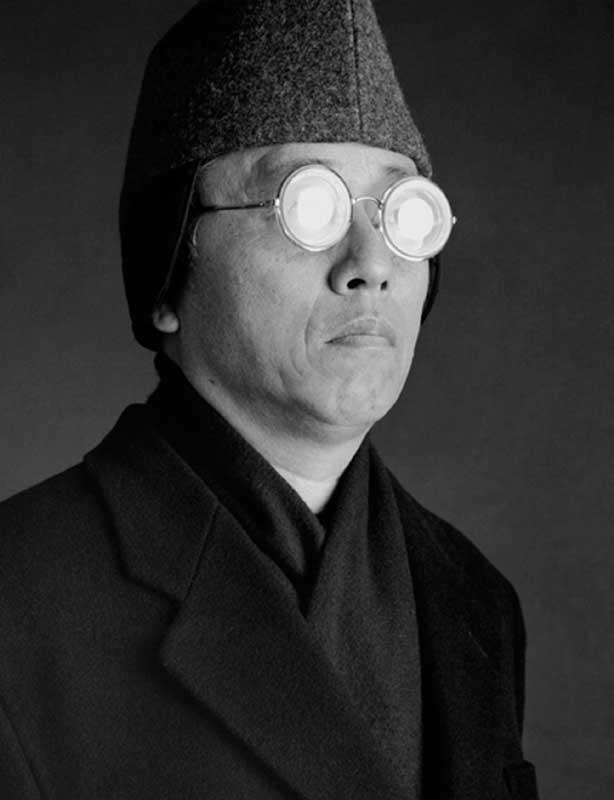

New York’s streets of the 1970s were full of eye-catching photography subjects: a thriving graffiti scene, angsty residents fearful of the city’s high crime rates, a tantalizingly gritty and pre-gentrified downtown Manhattan. When twentysomething Japanese photographer Hiroshi Sugimoto first moved to New York in 1974, he ventured out with his camera to document those very things. But it was ultimately in a very different type of street scene–the kind encased in glass at the city’s American Museum of Natural History–that he found lasting inspiration.

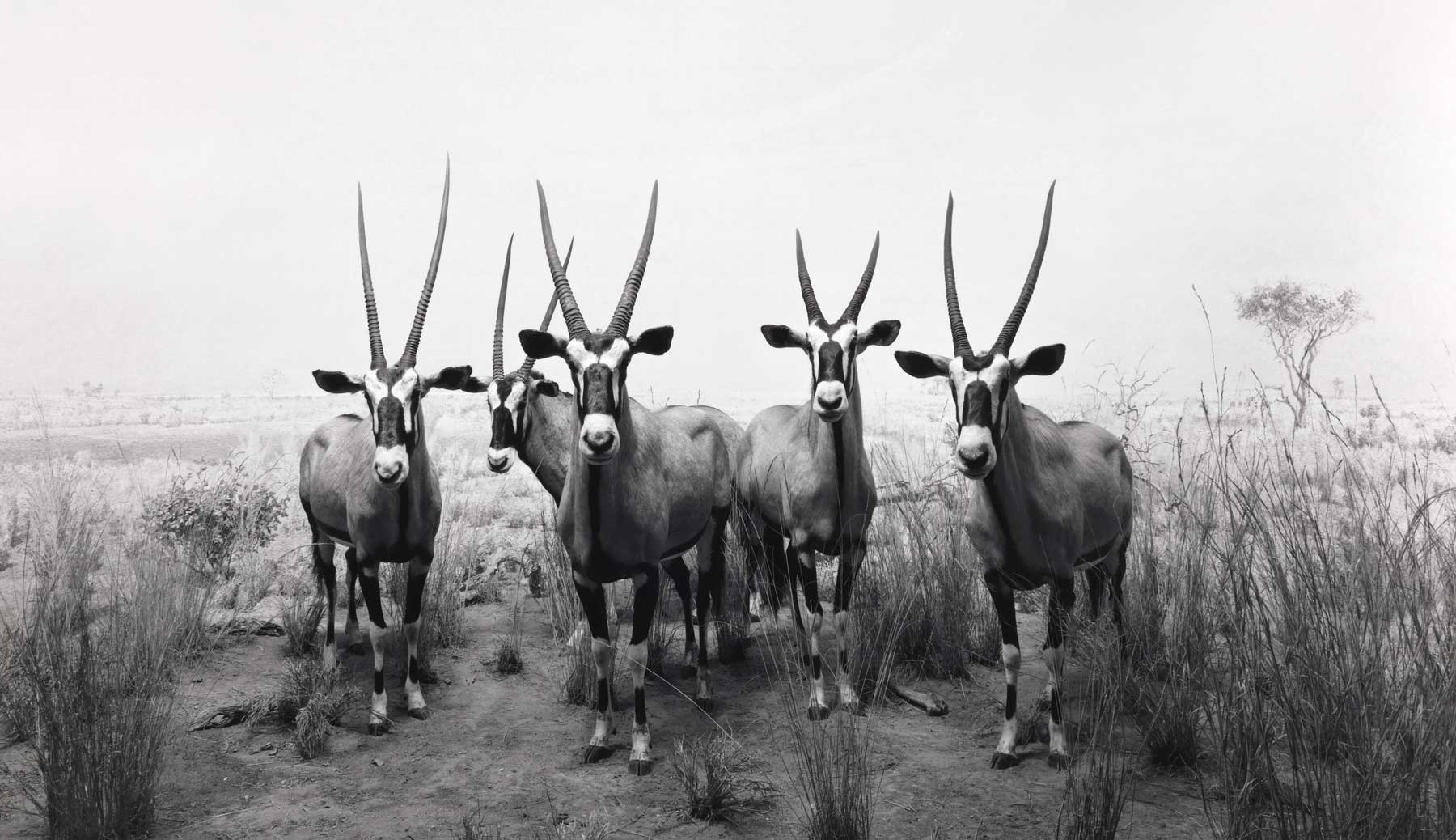

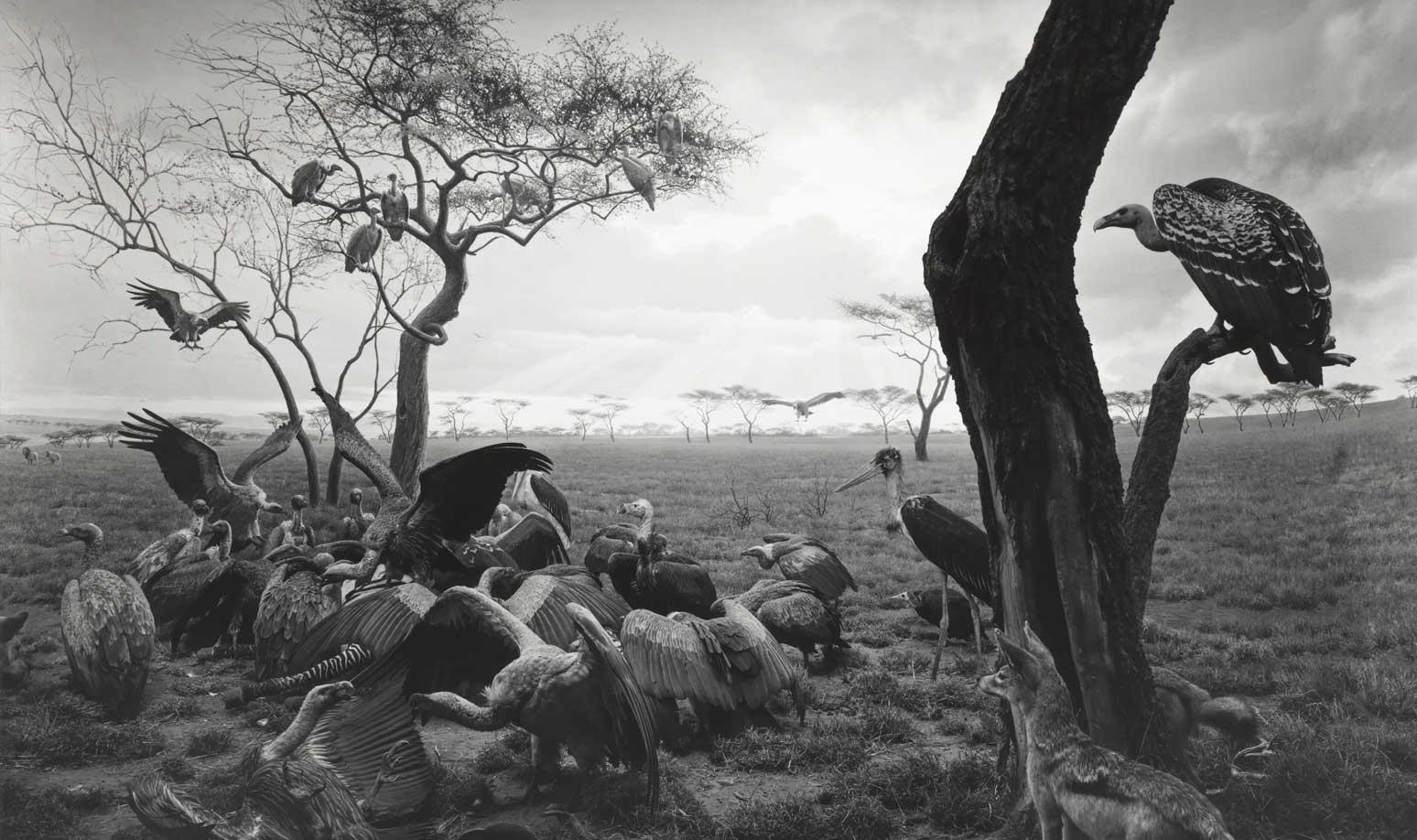

There, the dioramas of taxidermied wild animals fascinated Sugimoto. He saw a suspended tableau of lions feasting on a recently mauled zebra, before leaving their leftovers to vultures and hyenas waiting in the wings. The vista’s viciousness looked oddly familiar to the new Manhattanite. “I thought, ‘wow, this is New York,’” Sugimoto joked at the opening of his 2019 retrospective exhibition at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art.

But it was something else that eventually led to Dioramas, the first of his ongoing and celebrated photography series. “I all of a sudden realized that if I close my one eye then I get a photography view,” Sugimoto recounted. “The camera only has one lens, which means one eye. So if you close one eye you lose the sense of depth, and it gives you more reality.” By imitating a flat, photographic view of the motionless and fabricated scene in front of him, the stuffed animals, painted backdrop, and fake plants looked astoundingly alive.