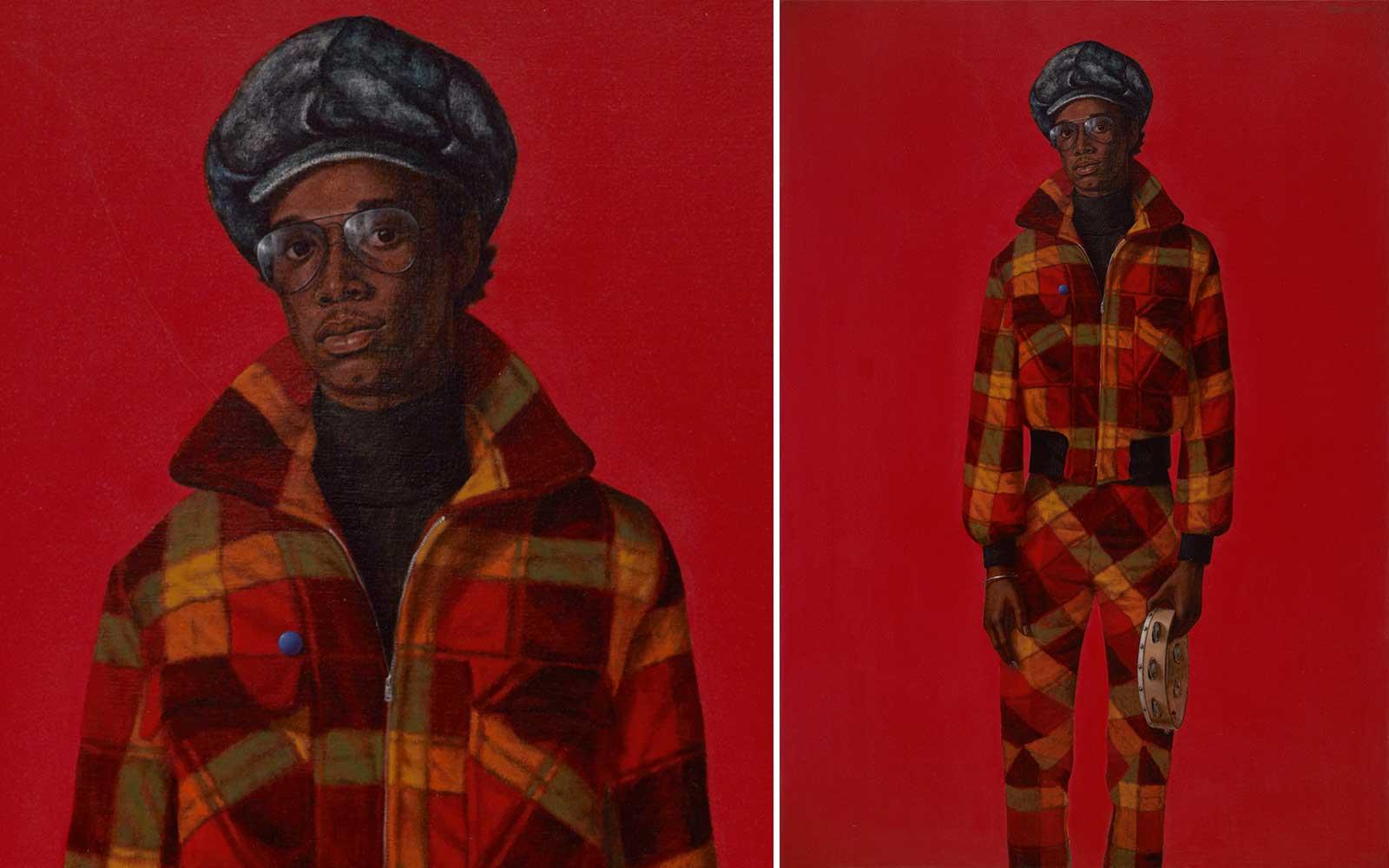

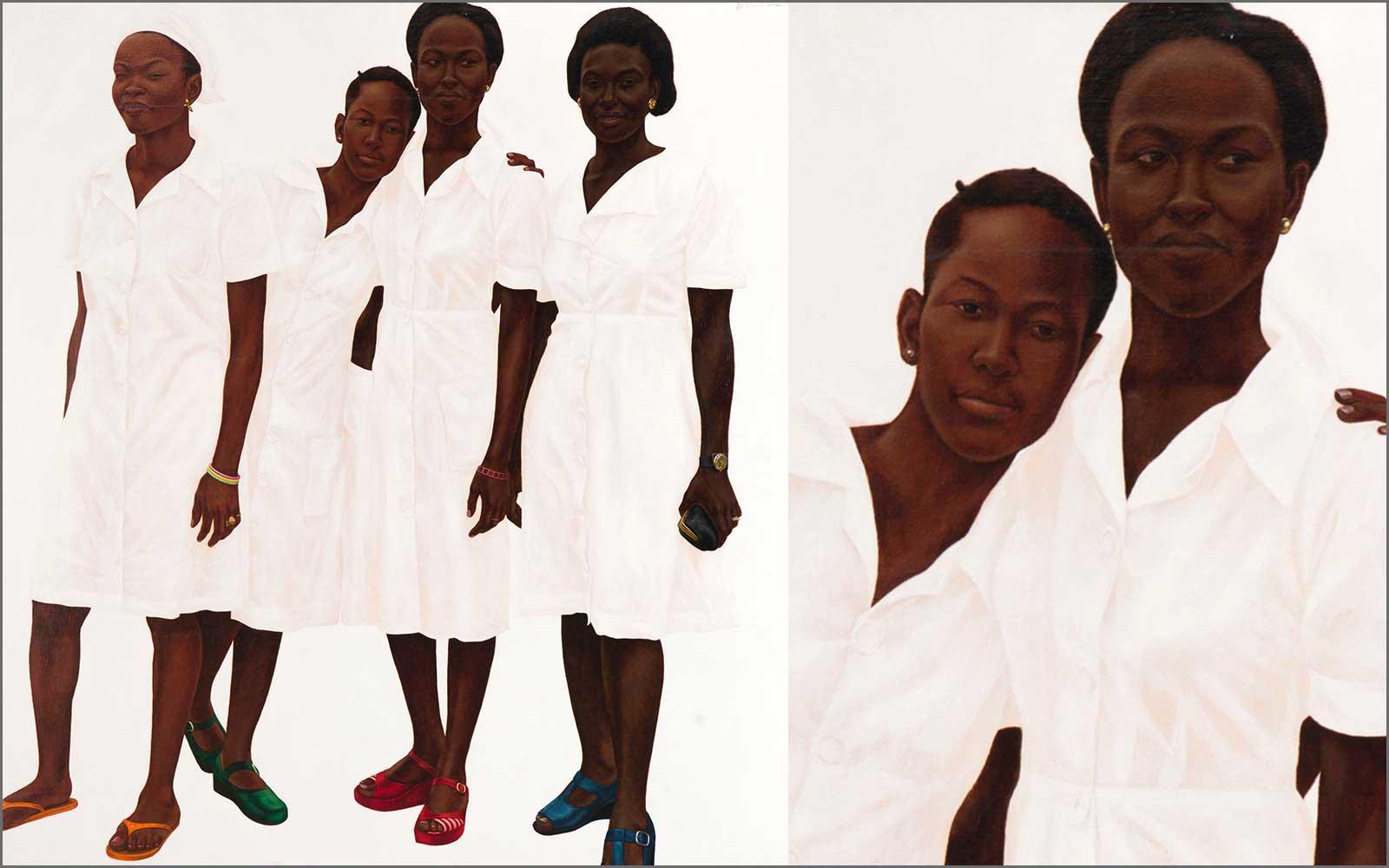

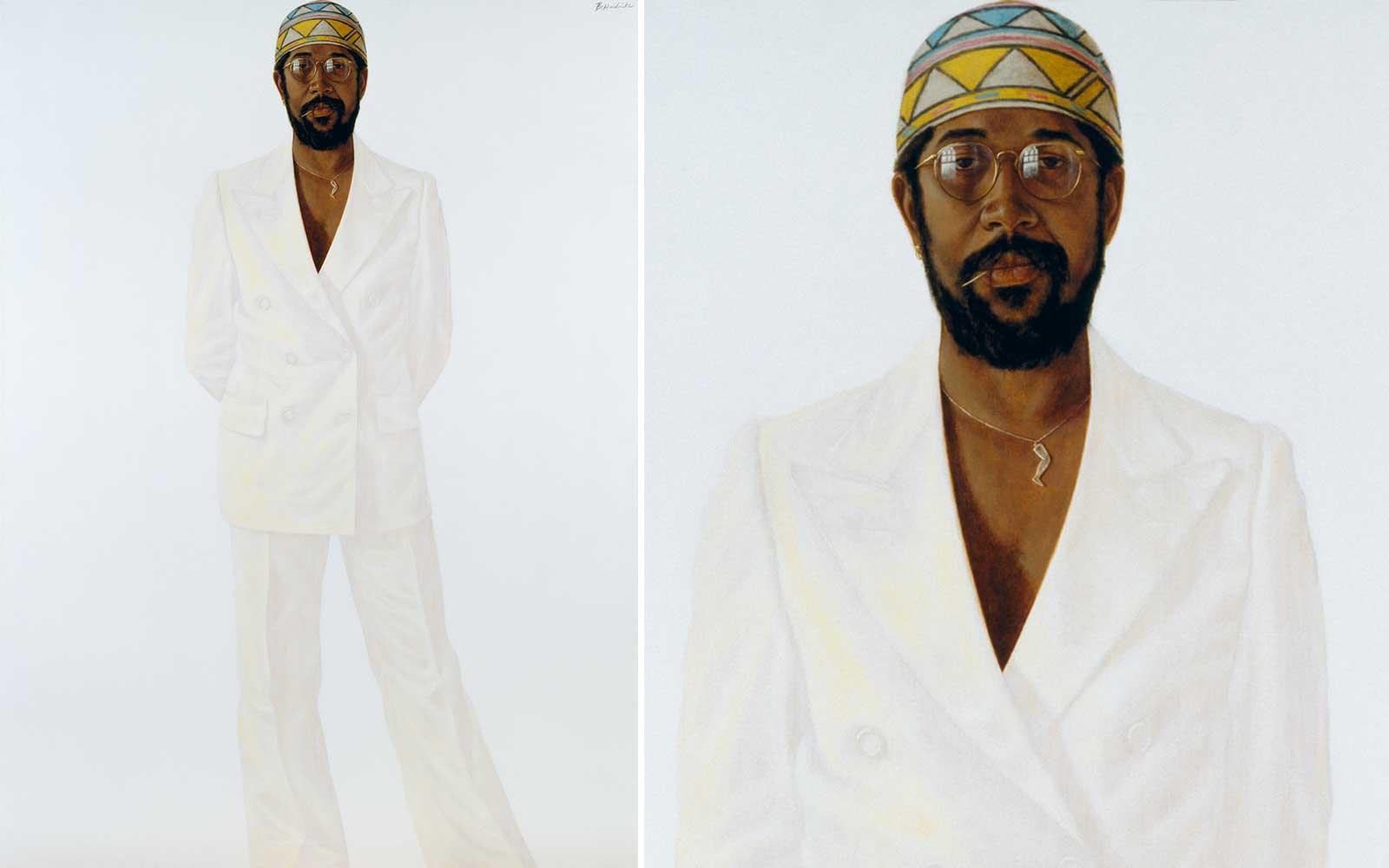

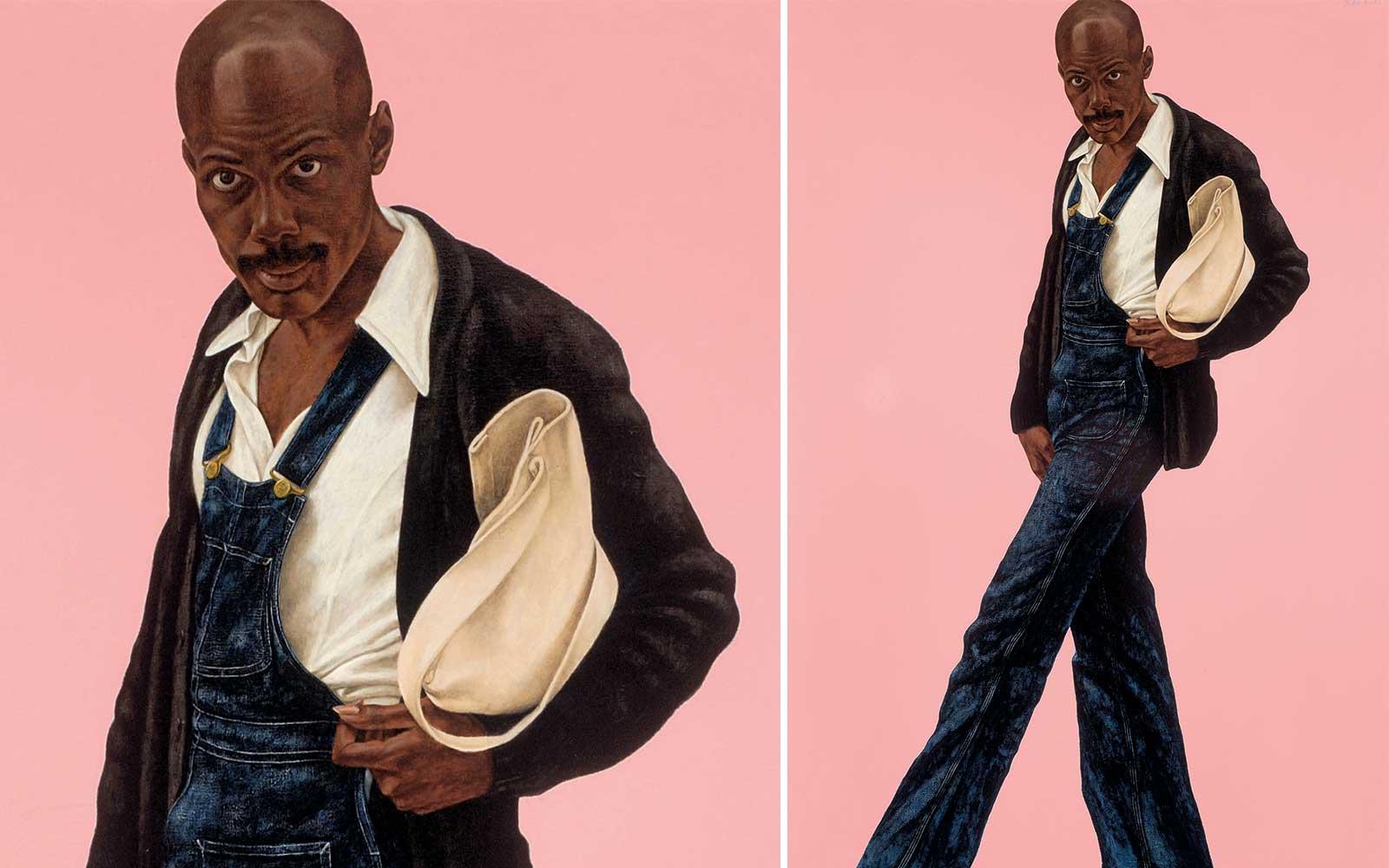

Barkley L. Hendricks: Portraits at the Frick, the Frick Collection’s overdue first solo exhibition of a Black artist and features fourteen large-scale portraits by Barkley L. Hendricks (1945-2017) meticulously selected by the Frick’s Curator Aimee Ng, and Consulting Curator Antwaun Sargent. Hendricks is known for his pioneering contemporary portraiture that depicted Black subjects in the traditions of the European Old Masters. Thus, the Frick Collection, with its iconic portraits by Rembrandt, Vermeer and Velázquez, is the perfect setting.

Art & Object sat down with Ng this month at The SisterYard cafe, in Frick Madison (the Frick Collection’s temporary home in the Breuer building), to ask what inspired the triumphant exhibition.

“It began with the question of, ‘Who can illuminate the spirit of the Frick through modern perspectives?’ she says. "This moment of move and transition is a chance to rethink the Frick’s identity, and Barkley is the kind of artist who Frick himself would’ve wanted.” She credits two forces for bringing Hendricks to Frick Madison: the cosmos, and Antwaun Sargent.

“Barkley was very concerned with painters of the past, the Old Masters, the Renaissance,” Sargent insists over the phone, on his way from New York City to Los Angeles to open another exhibition. “I thought if you really want to make a contemporary connection between the Frick and artists today, it has to be Barkley Hendricks.” Hendricks even painted Miss T in response to the works of Giovanni Battista Moroni, whose figures also hang in the Frick Madison.

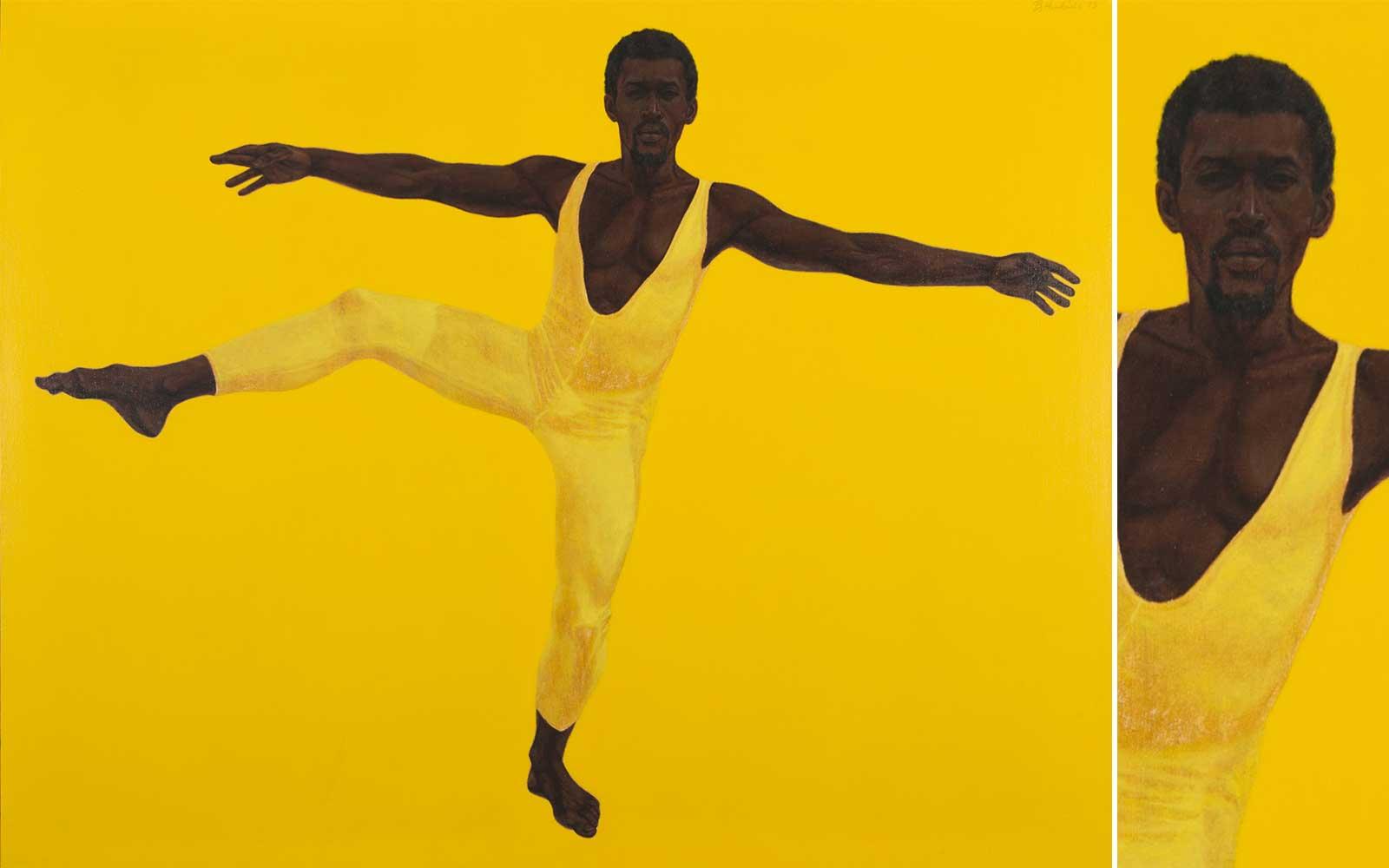

Indeed, there is an effortless comparison to be made between Hendricks and Rembrandt, Van Dyck and Whistler. Hendricks’ portraits are contemporary vessels of classical techniques; deconstructed to the levels of brushstroke and paint-mixing, Hendricks rendered Old Master methods for twentieth-century subjects. The iridescent gold stage in Lawdy Mama was a culmination of two years spent finessing the art of leafing, resulting in the icon of a Black woman (modeled by Hendricks’ cousin) that is equivalent to venerable Byzantine mosaics.

Yet Hendricks’ portraiture also differs from that of his predecessors; Ng cites his technological fascination and flexibility—“his handiness”—as innovation and believes Hendricks saw his paintings as both portraits and abstractions.

For Sargent, Hendricks’ subjects are what distinguish the artist from the Old Masters; Hendricks photographed and painted his wife, students, friends, gay and interracial couples, and people he encountered on the street. He immortalized individuals who existed outside the dominant culture. But Sargent makes an important distinction. “Hendricks didn’t give people back their humanity, he just recorded it,” says Sargent. “He upset the power dynamic of Old Master paintings.”