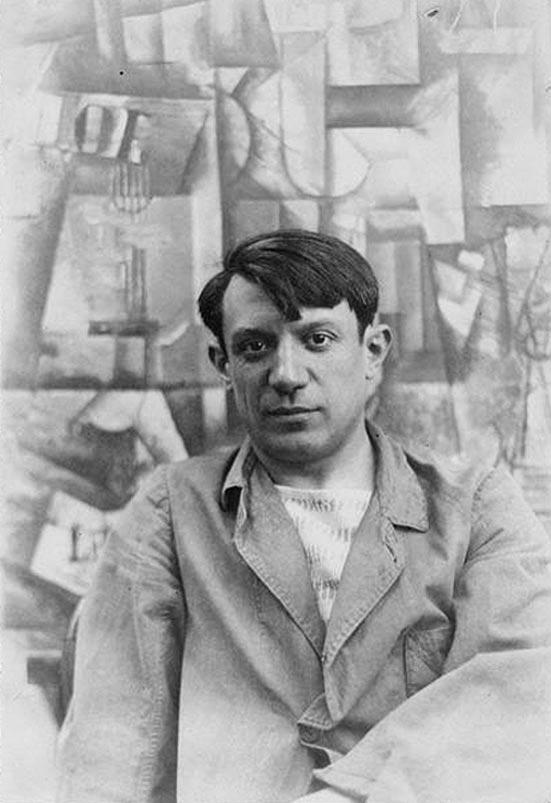

It was August of 1912, and Cubist comrades Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque were summering in the southern French town of Sorgues. Taking cover in the countryside far from Paris’s curious onlookers (and more than a handful of naysayers), the two modernists forged onward together in their pioneering new painting style that fractured traditional pictorial perspective with overlapping tessellated planes.

Braque was wandering around town one day when he noticed a wallpaper shop on the rue Joseph Vernet. The window displayed a roll of faux bois (oak grain) decorative paper that probably seemed ordinary to most, but was a revelation to the artist. Having grown up in a family of house painters who taught him the tricks of their trade–such as how to imitate marble or woodgrain effects with paint alone–he could reproduce many textures with a paintbrush and some combs. But a readymade roll of the stuff unraveled an entirely new set of visual, theoretical, and practical opportunities.

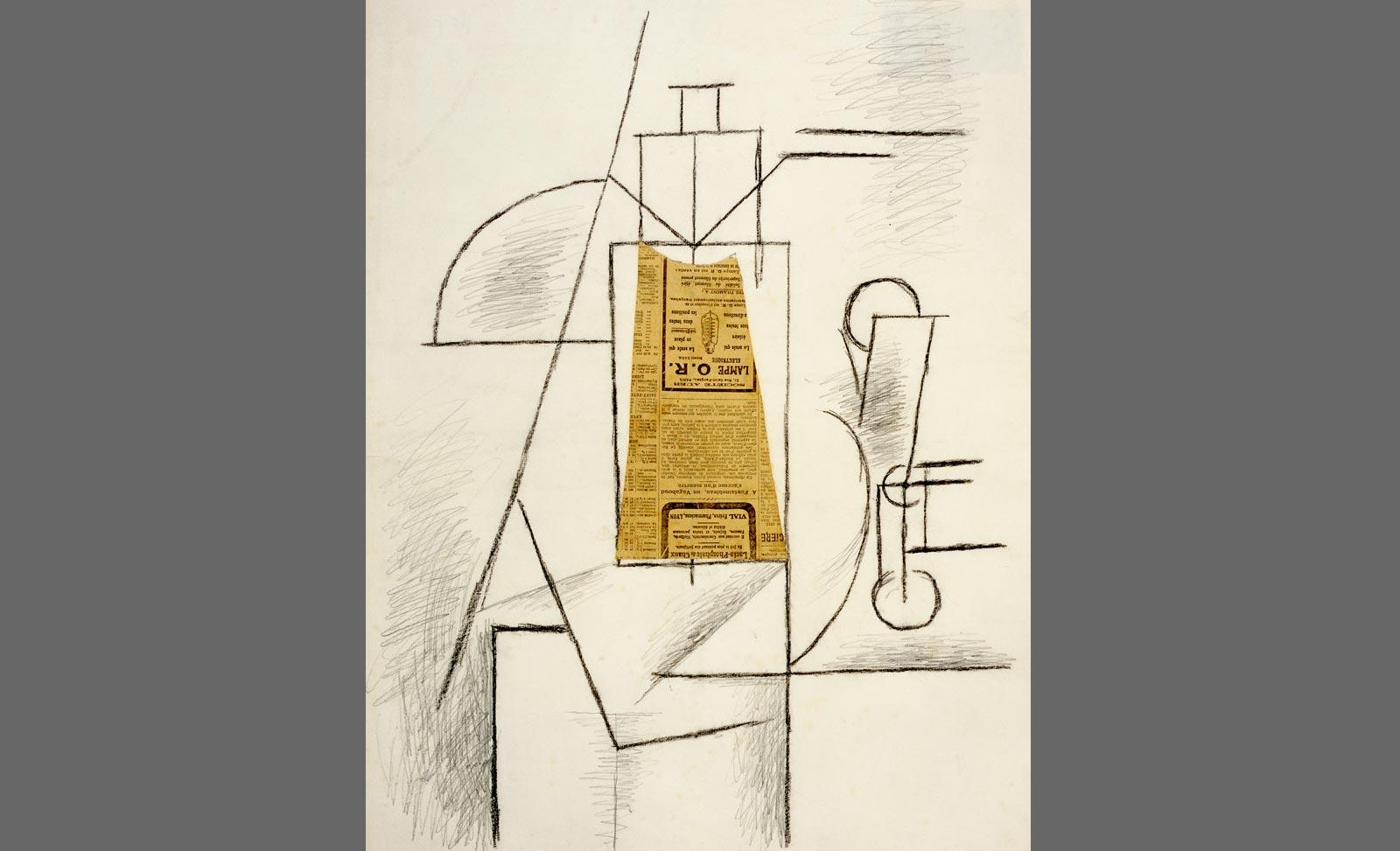

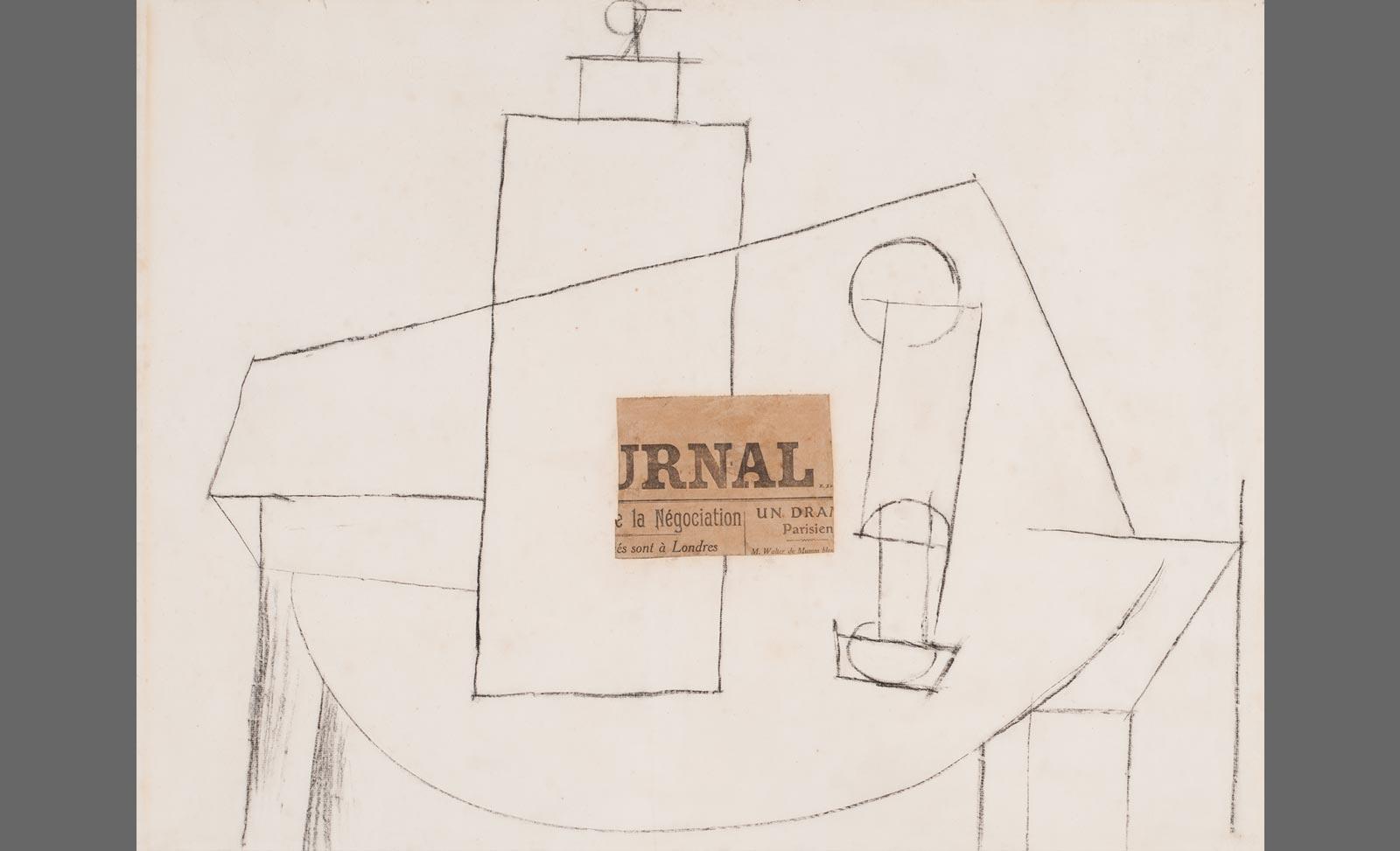

Not wanting his prolific pal to catch wind of his discovery, Braque waited a few days until Picasso left town for Paris and then made his seminal purchase. “I had bought the paper and completed Fruit Dish and Glass (1912) before he returned,” Braque recalled to art collector and scholar Douglas Cooper decades later, upon seeing his still life (now credited as the first Cubist papier collé) hanging in Cooper’s study.

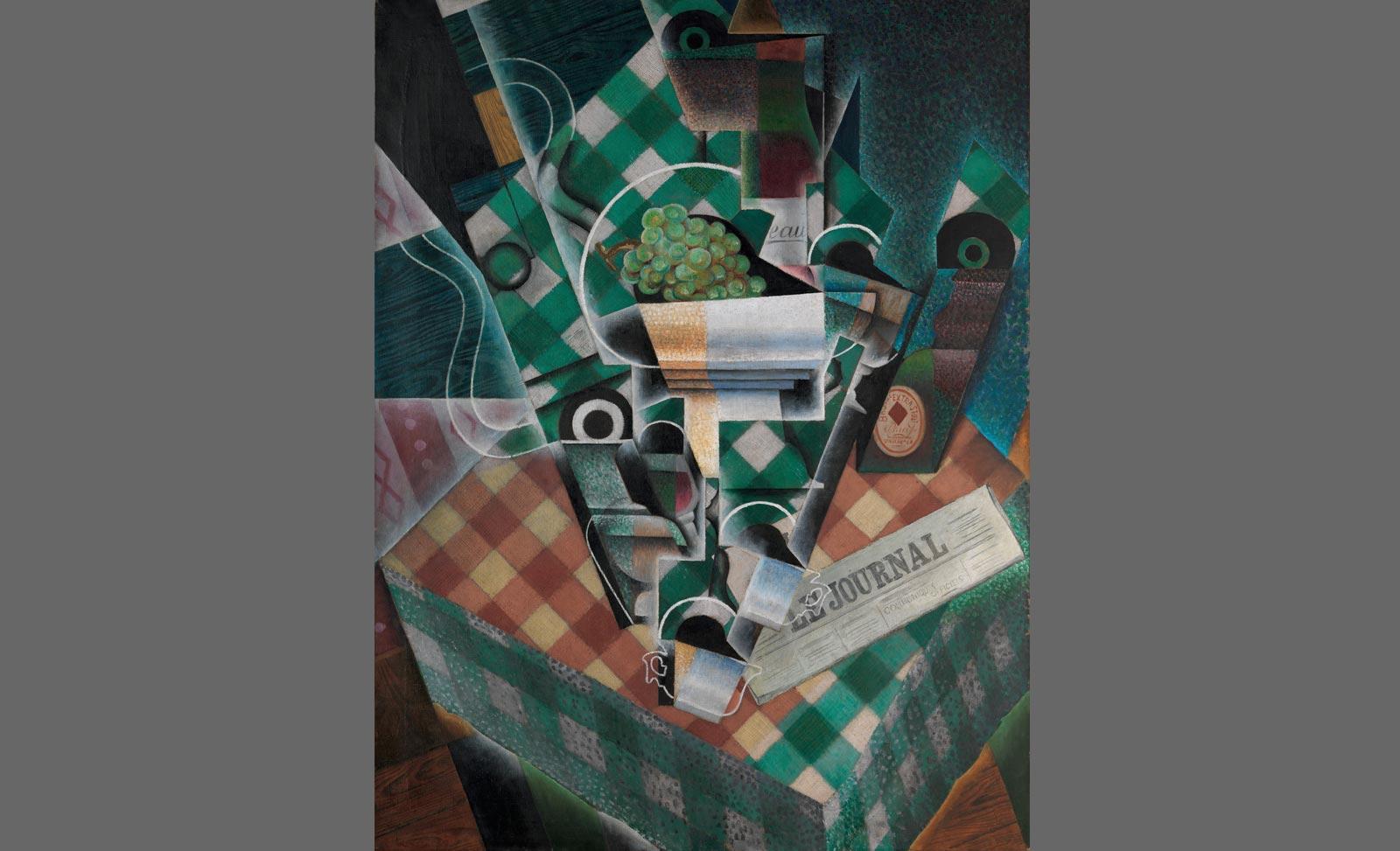

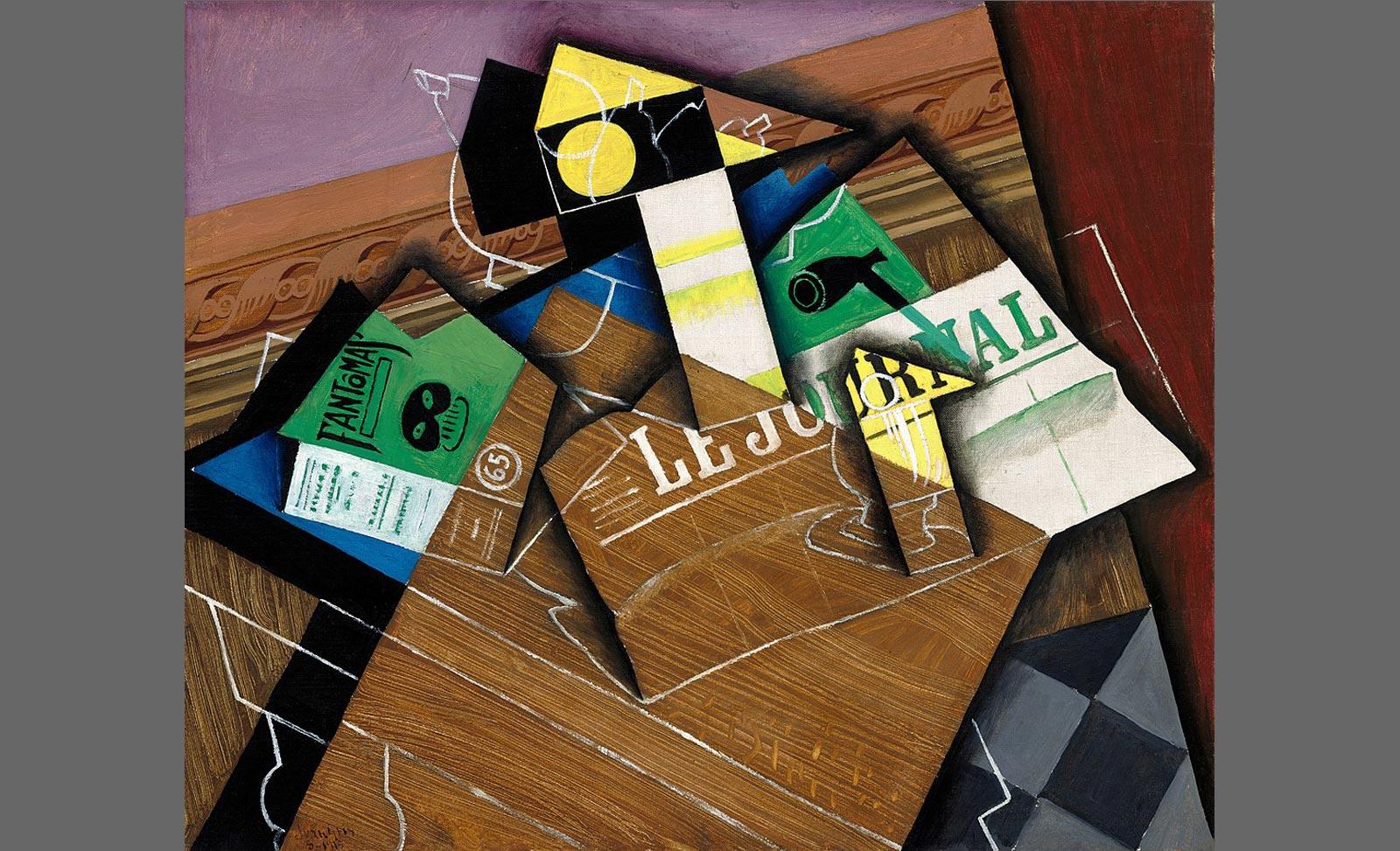

Braque’s cheeky anecdote recounts the beginnings of one of the most revolutionary genres of work in twentieth-century art: Cubist collages and papier collé. The names of these terms are derived from the French word for gluing, coller, since the Cubists pasted a host of foreign objects onto their works including (but not limited to): wallpaper, newsprint, sheet music, oil cloth, calling cards, and rope.