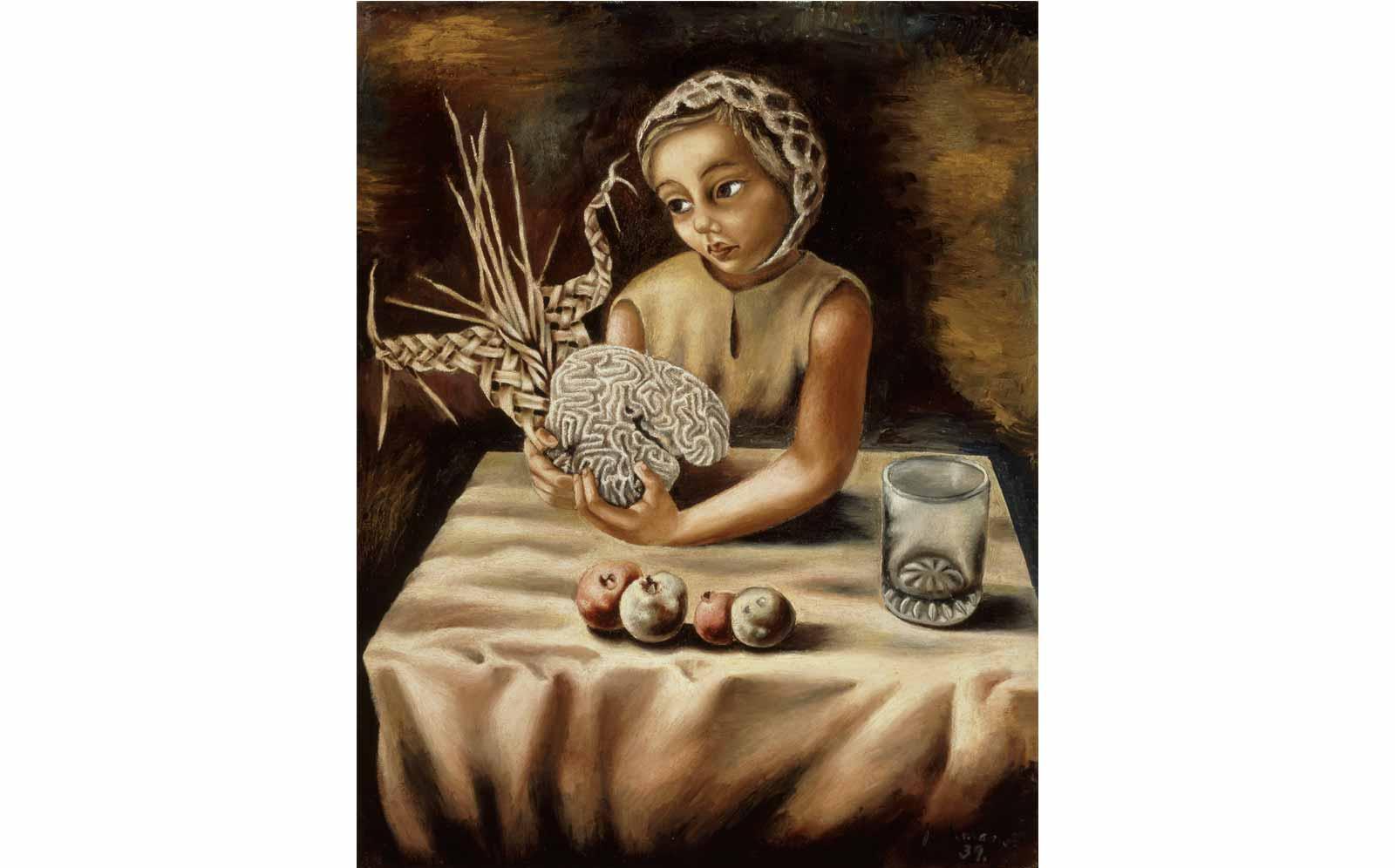

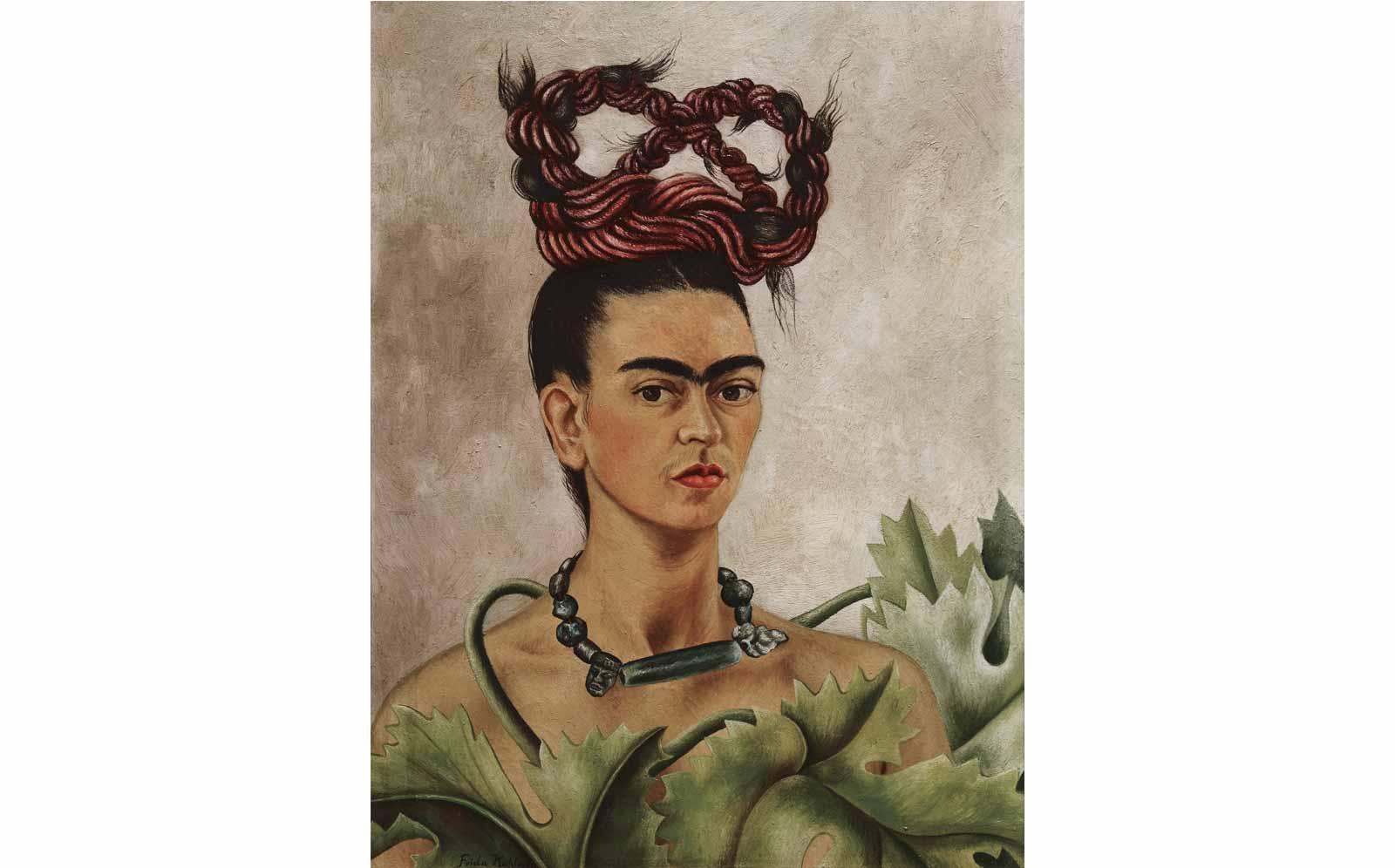

Mexican Modernist, surrealist, magical realist, or naïve artist–it has always been challenging to categorize Frida Kahlo. Arguably the most famous female artist of all time, she was never one for convention.

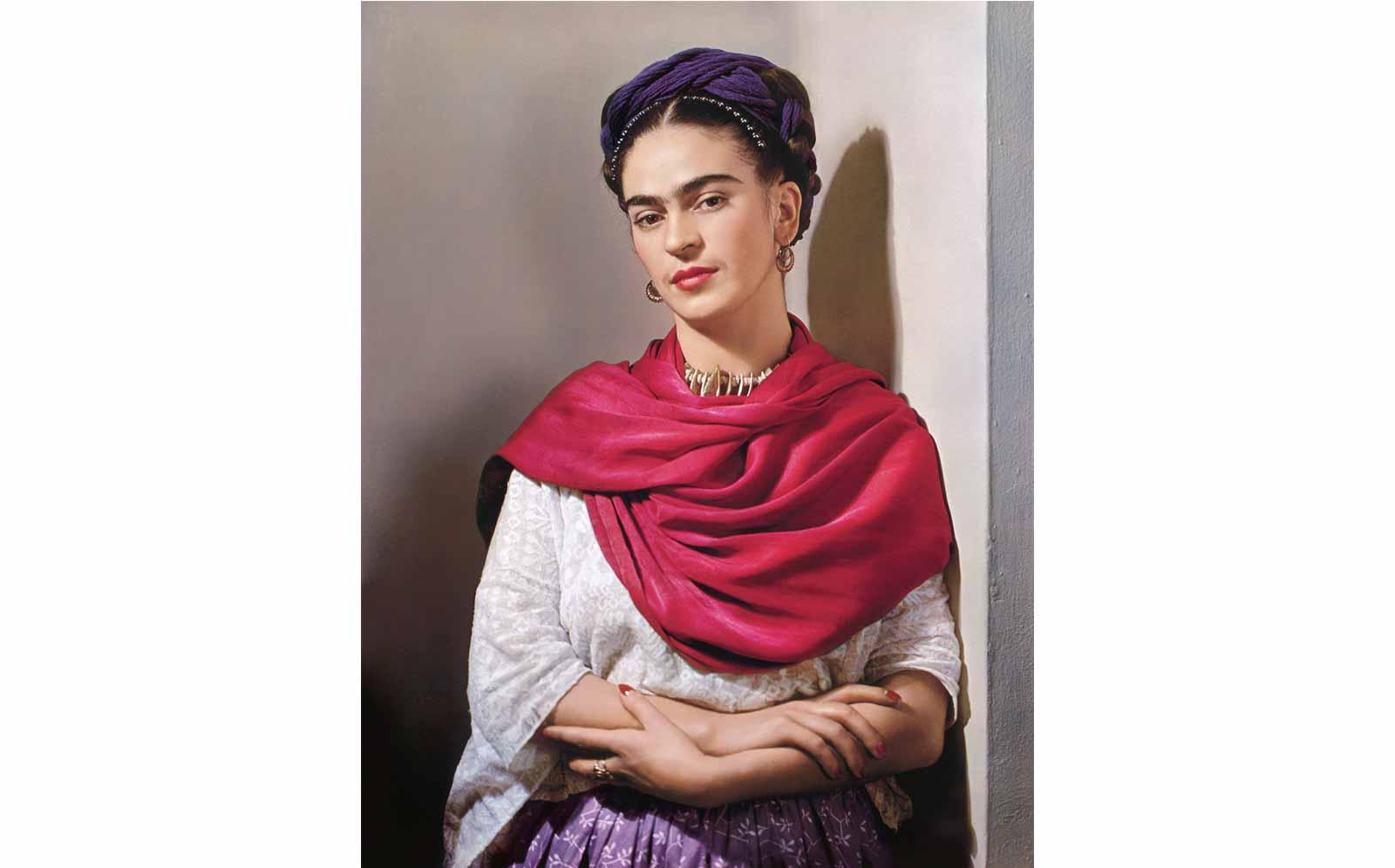

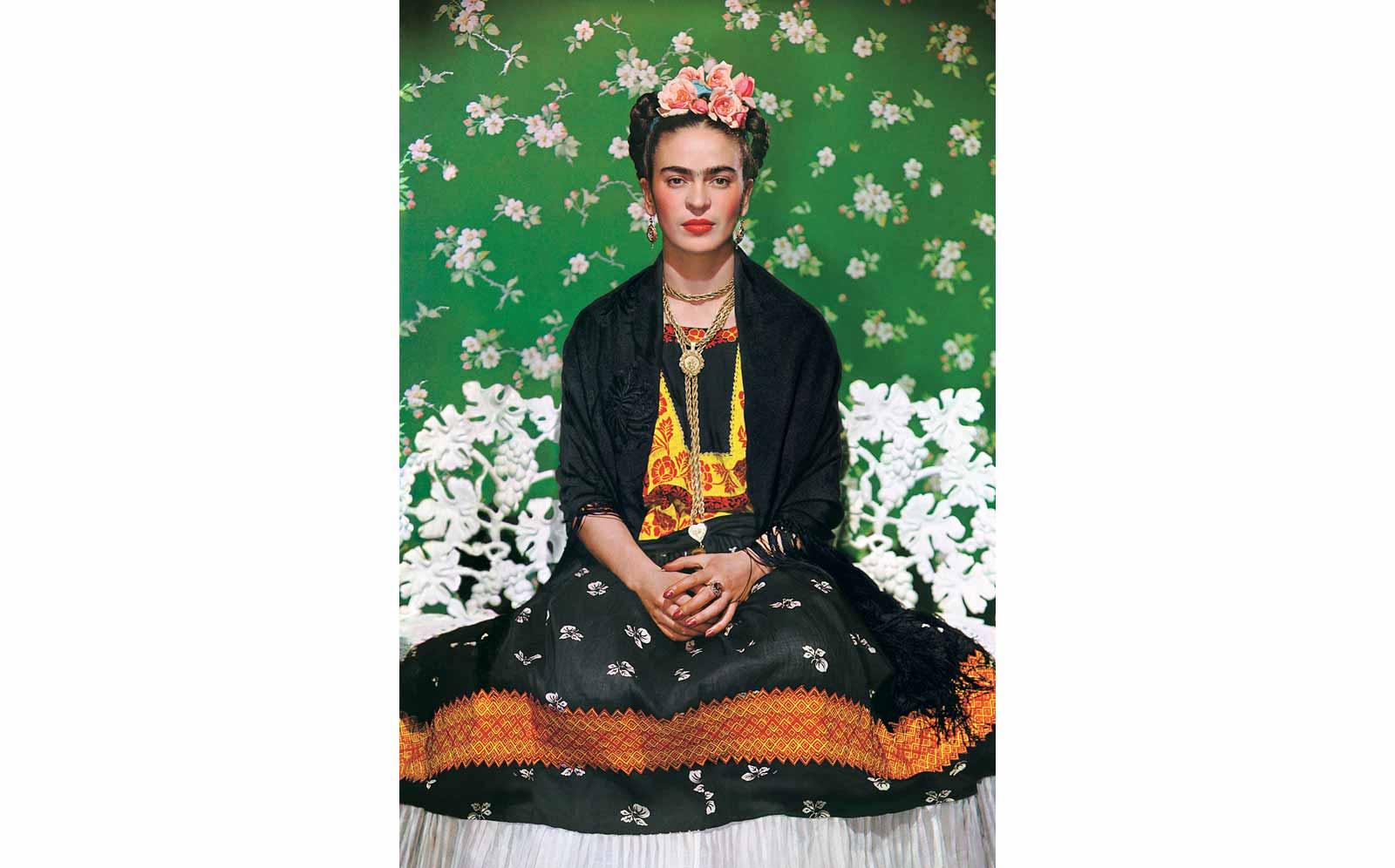

An internet search for Frida Kahlo results in everything “Fridamania,” including socks, throw pillows, mugs, cell phone cases, and sneakers–even a controversial Barbie doll and an upcoming line of cosmetics, complete with unibrow palette. While Kahlo is now an art rock star, this wasn’t always the case. Jennifer Dasal, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the North Carolina Museum of Art (NCMA), explains that Frida was considered a fascinating personality, and more a subject of curiosity during her lifetime. “…Frida’s art wasn’t hugely touted—but her clothing and appearance were, and that’s what got most of the attention.” Things began changing after Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo by Hayden Herrera was published in 1983, Dasal observes. “[Then] after Salma Hayek’s…2002 biopic Frida, things really escalated.”