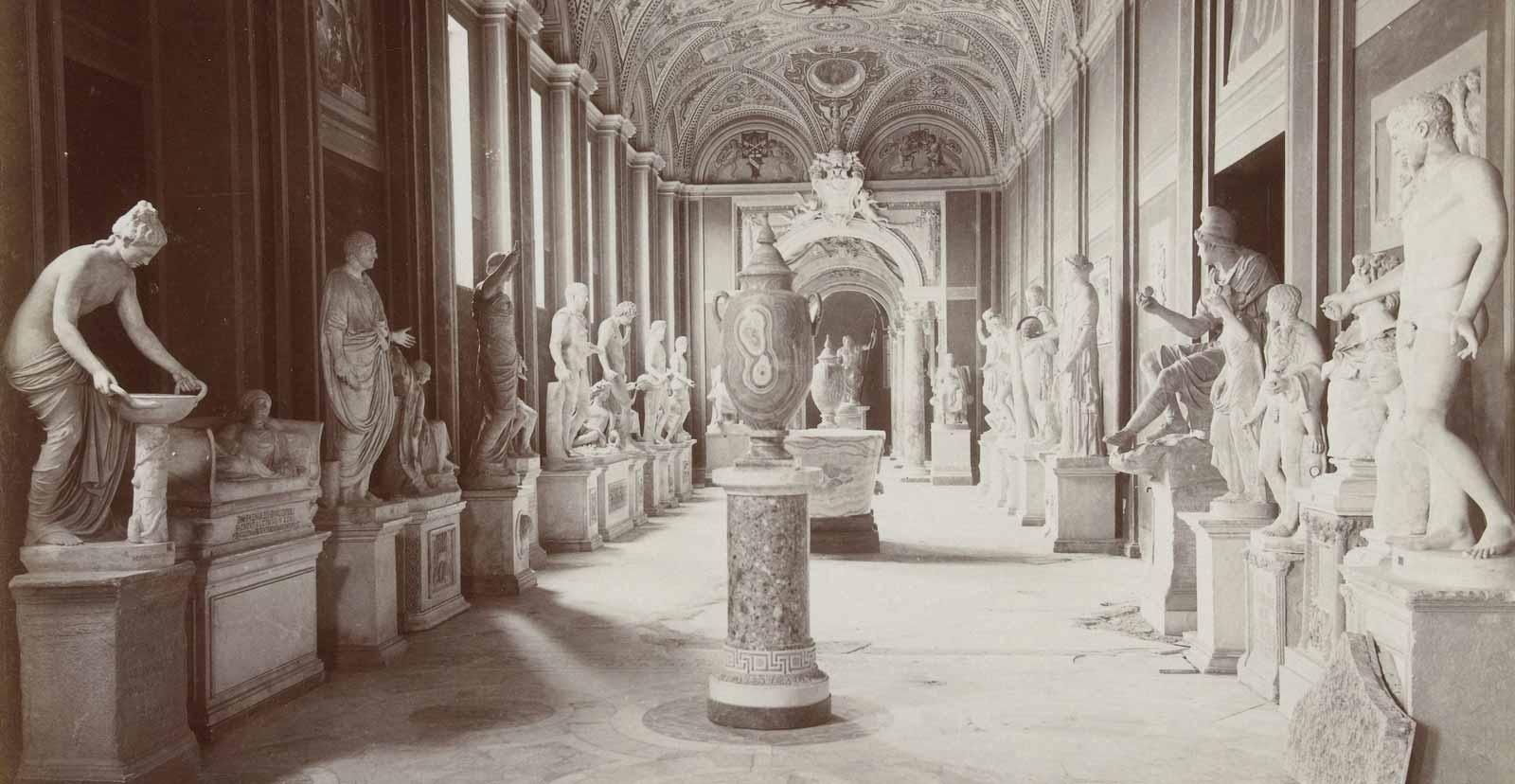

Ancient Rome was said to have two populations, equal in size, one of flesh and one of marble. Thousands of examples of this second group still inhabit the museums and storerooms of the city, their antique bodies and busts lining galleries and halls. The display of numerous sculptures, often crammed into a single space, emerged following the rediscovery of antiquity in the 15th century, and remains prevalent in many museums today. Confronted with rows of white marble faces, even the most interested viewer may struggle to see the whole as a historic collection and lose sight of the individuals being represented. Oversaturation creates the impression that one bust looks just like another, and discourages visitors from lingering, studying the features, to looking for the personality in the portrait.

How

Photography

Can Reveal

Personality

in Ancient

Portraiture

Luigi Spina’s Faces of Rome brings us a more intimate understanding of ancient marble busts and the people behind them.

Faces of Rome runs through September 22, 2019 at Rome’s Museo Centrale Montemartini and is accompanied by a catalogue with full-page images, Volti di Roma alla Centrale Montemartini, edited by Claudio Parisi Presicce and Luigi Spina (Silvana Editoriale, Milan 2019).

Yet this is exactly what the exhibition Faces of Rome (Volti di Roma) at Rome’s Museo Centrale Montemartini seeks to counter. Curated by Claudio Parisi Presicce, the show comprises 60 images by photographer Luigi Spina of 37 ancient sculptures in the museum’s permanent collection. Taken with a view camera and hand-printed by Spina, the enlarged black and white photographs are reproduced at life-size and arranged on freestanding steel frames throughout the museum, positioned among the existing objects. At first, the premise of showing photographs of statues that are already on display in the museum might seem redundant, but Spina’s work brings a new dimension to the ancient art.

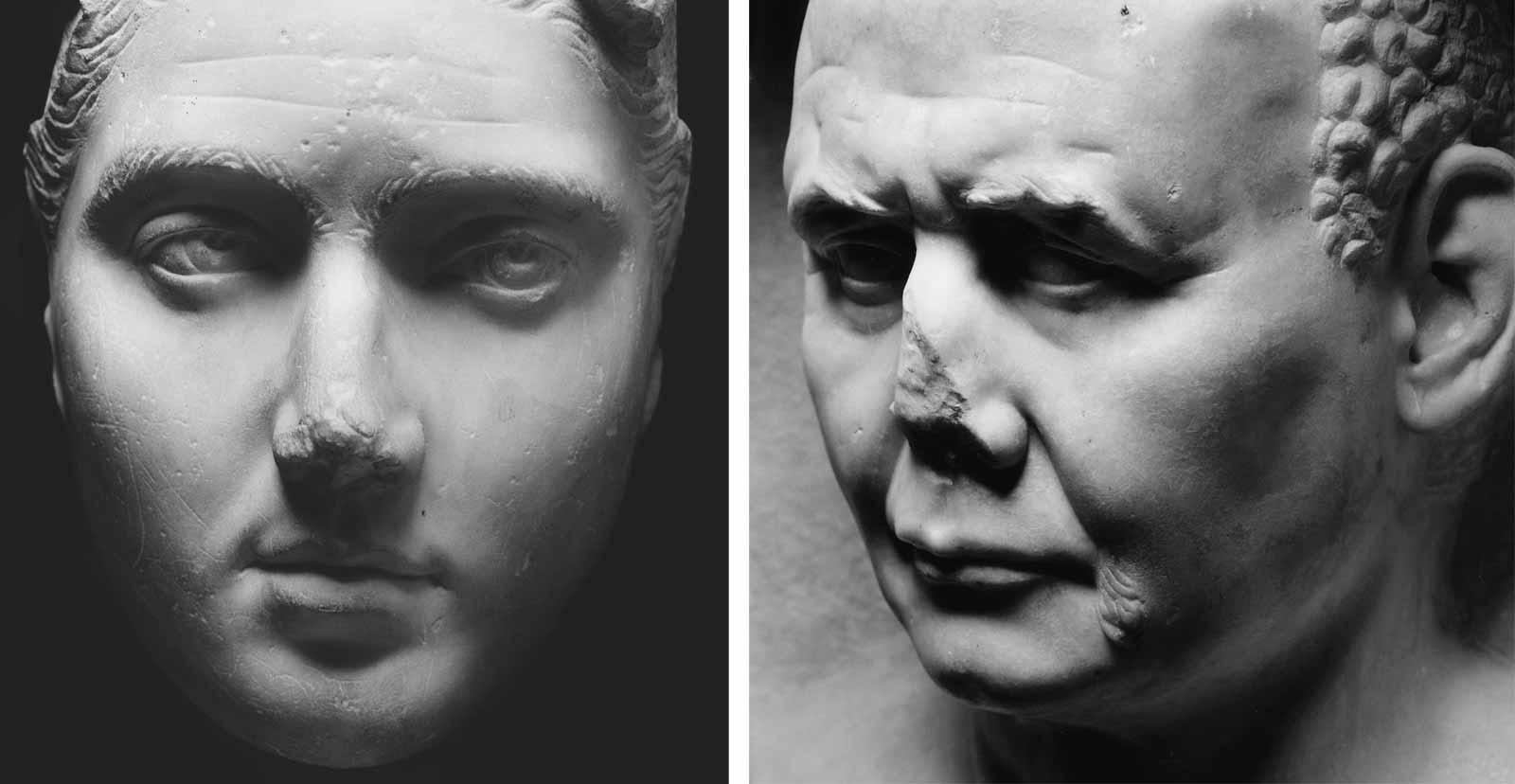

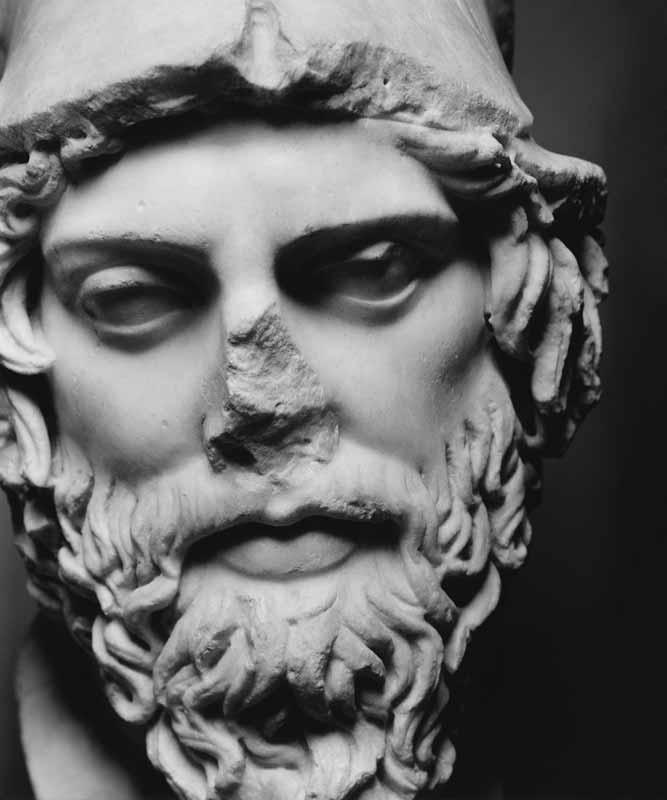

The origins of the exhibition are a much larger project of cataloguing all 696 ancient portraits in Rome’s Capitoline Museums, carried out between 1983 and 2014. Yet while the emphasis of the academic project was on documenting busts as historic objects, the images in the current exhibition have more in common with contemporary portrait photography, focusing on specific facial features in order to bring out the personality of those depicted. The aim is to create “a visual dialogue between ancient faces and the emotions captured by the camera lens;” through photography, Spina seeks to “establish a confrontation between us and the people represented [in marble].” By finding familiar expressions–the knowing smile and eyes of a bearded individual; the serious, even melancholic, stare of an old man–Spina wants to erase “distances in time” between their era and ours. In turn, the approach highlights the remarkable attention with which ancient artists captured their subjects, allowing a further level of appreciation for their workmanship.

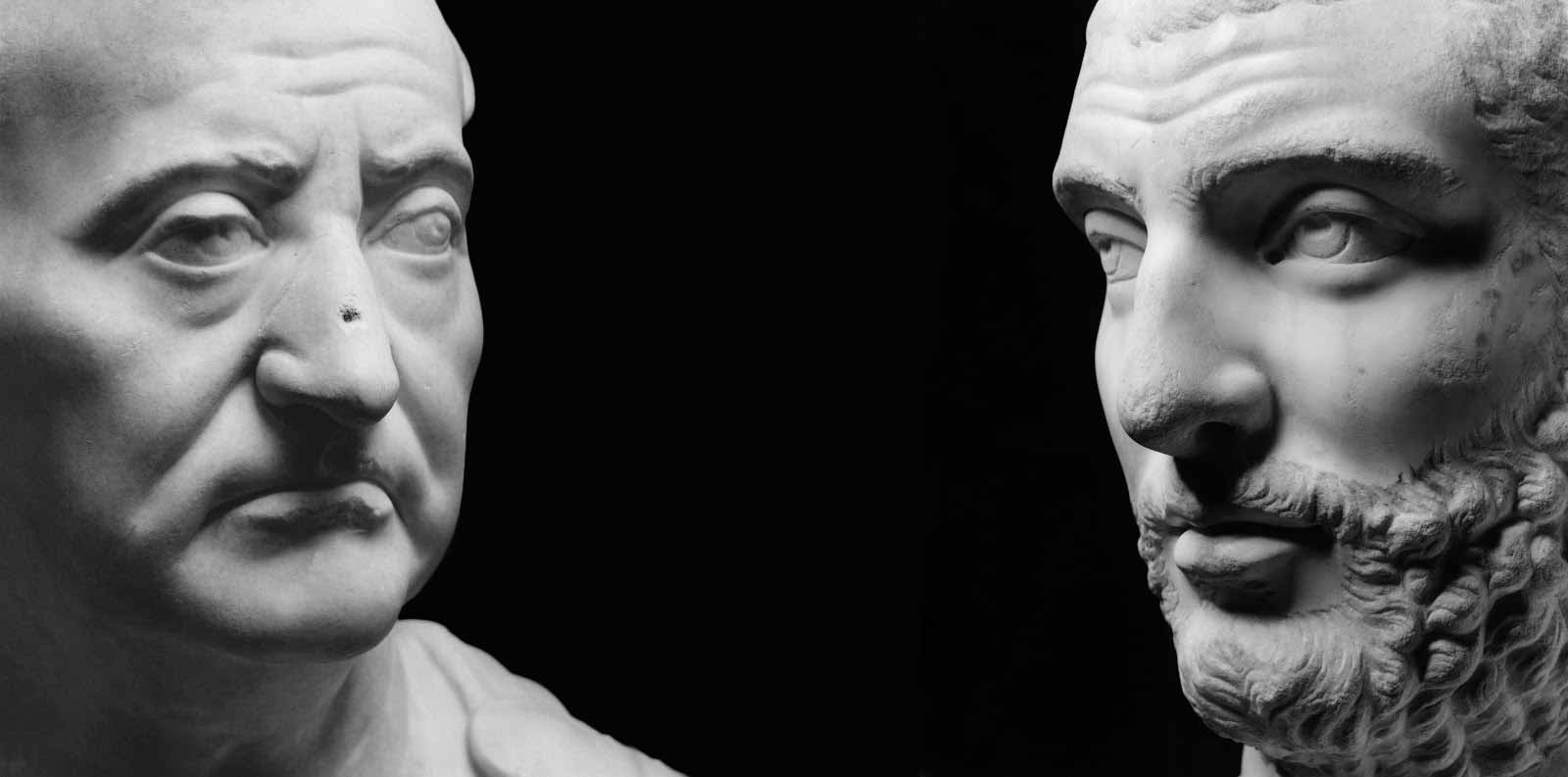

The choice of statues included in the exhibition is not based on the historical significance of the people, instead Spina selects “portraits that show the human side.” Even though the figures include members of the imperial family, deities, heroes, athletes, politicians, and a poet, the absence of accompanying captions with information about the bust, as well as the physical separation of the photographs from where the actual objects are displayed, anonymizes them. Indeed, it is the portraits of now unknown individuals that are among the most evocative images. In particular, the black and white photographs work best with ‘veristic’ busts, a trend of ‘warts and all’ portraiture that emerged in ancient Italy in the first century BC. In contrast to idealized, youthful faces, individuals were represented in the later stages of life. With these examples, the deep lines of their faces are accentuated by the use of light and shadow, the shading in the photographs draws out the texture and ripples of the skin in a way that the naked eye does not when confronted with the luminescence of the marble itself.

The presence of color on ancient statues has become a source of intense scholarly interest, as new research increasingly shows how paint and ornament were commonly applied to white marble figures. While the head of an Amazon excavated in 2006 at Herculaneum was found with her pupils, irises, and eyelashes delicately picked out in paint, the extent of its use was varied and is often unclear. Some modern efforts at reconstruction insist on coloring entire statues in garishly rich pigments, to the point that the marble is rendered invisible. This painting of statues is sometimes spoken of in terms of adding ‘realism’ to sculptures, yet in the exhibition we see how the absence of color is no bar to expressiveness.

The anonymity of the portraits also allows appreciation of the statues to move beyond the scholarly preoccupation with categorizing and dating. Two traditional strands of research in Roman sculpture have been the connecting of busts to known persons, and ascertaining whether certain pieces are ‘copies’ (itself a contentious term) of earlier Classical and Hellenistic era Greek works. Such approaches are important for understanding the historical context in which the statues were produced and such details are often the focus of interpretation in museums. But this runs the risk of overshadowing what can be discerned from an individual expression. By removing the question of whether a portrait is actually that of an emperor, we are left with a steely, self-assured man; by not fixating on which fifth century BC Greek general a Roman era bust ‘copies’, attention is focused on what his thoughtful, downward gaze conveys.

Just as the photographs are angled and lit to present a particular impression of the subject, so too the busts themselves are not candid ‘snapshots’ of ancient people. They are carefully considered studies, intended to communicate exactly what the subject and artist wanted an audience to see. Even the agedness was deliberate and, in some cases, likely exaggerated.

In Roman society, portraiture represented an individual’s identity and a marble image stood in for them when they were not present; carved in stone, a statue was meant to endure and preserve the memory of the subject (it is not surprising that a number of the sculptures included in the exhibition are originally from funerary monuments). This implies we should expect to find meaning in the details of a portrait–the ‘veristic’ style has been connected with Republican virtue, and particular hairstyles are argued to indicate alignment with imperial dynasties (some still maintain that the emperor Hadrian’s beard is a signifier of his love of Greek culture).

Faces of Rome also shows the relevance of animation and emotion as a consideration in the carving of a bust. In this way “the photos become a tool for understanding ancient artworks” because they encourage us to see beyond historical interpretation and think about the personality represented in the object.

Such visuals cannot be easily replicated. Spina worked when the museum was closed and “the silence of the public’s absence allowed a privileged dialogue with these portraits.” Perhaps more importantly, this allowed the statues to be lit in a manner that the everyday conditions do not allow. That the photography was carried out in Museo Centrale Montemartini is particularly fitting. Located outside of the ancient city walls, in a former industrial zone occupied by gasometers, market buildings, and warehouses, the museum was originally Rome’s first public power plant. Opened in 1912 and decommissioned in the 1960s, since 1997 it has housed an important collection of ancient sculpture excavated in the city, while also retaining much of the original machinery. Paralleling the light and dark of the photographs, the heavy, black iron turbines and engines provide an appealing contrast to the graceful, white marble statuary. As Spina points out, “few museums in the world offer this extraordinary visual experience… [where] there are two overlapping times.”