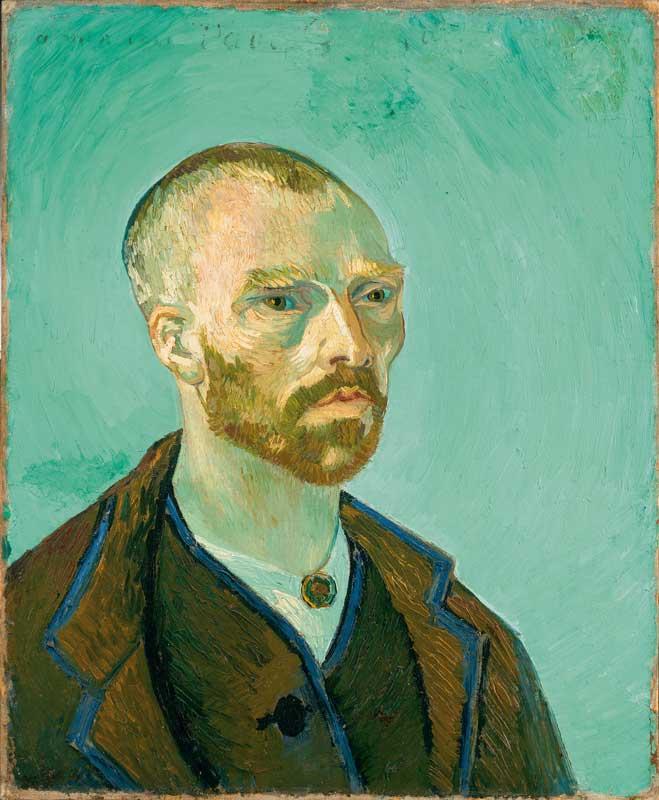

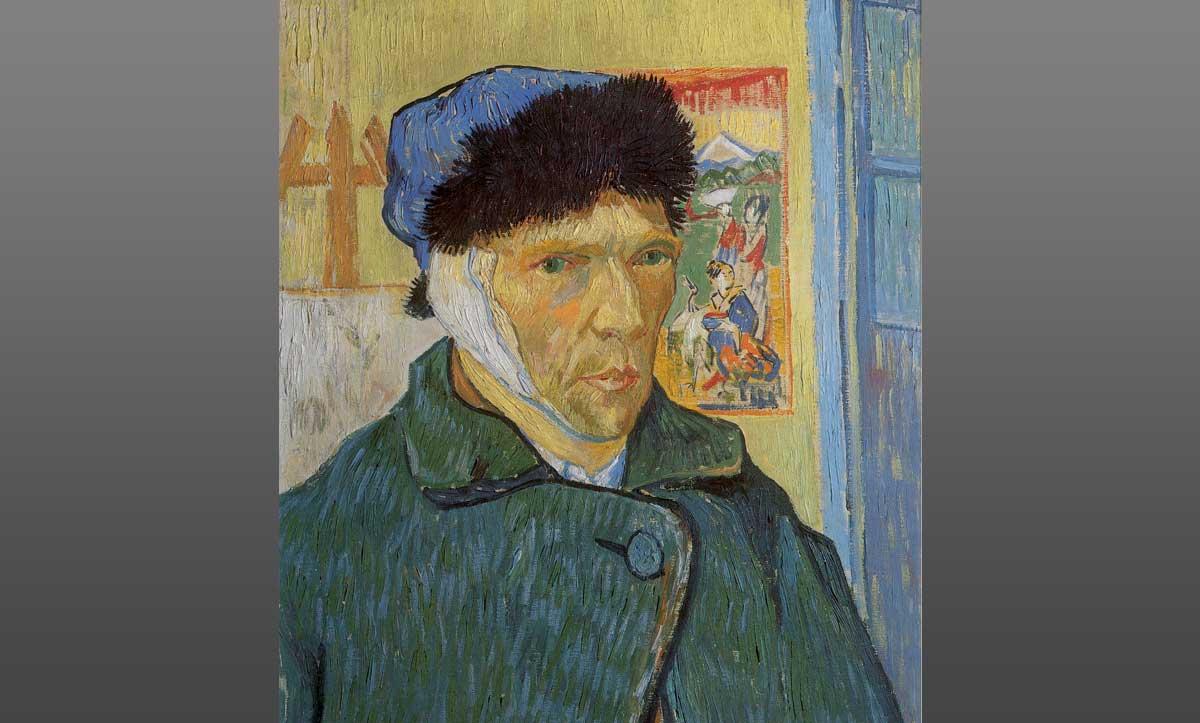

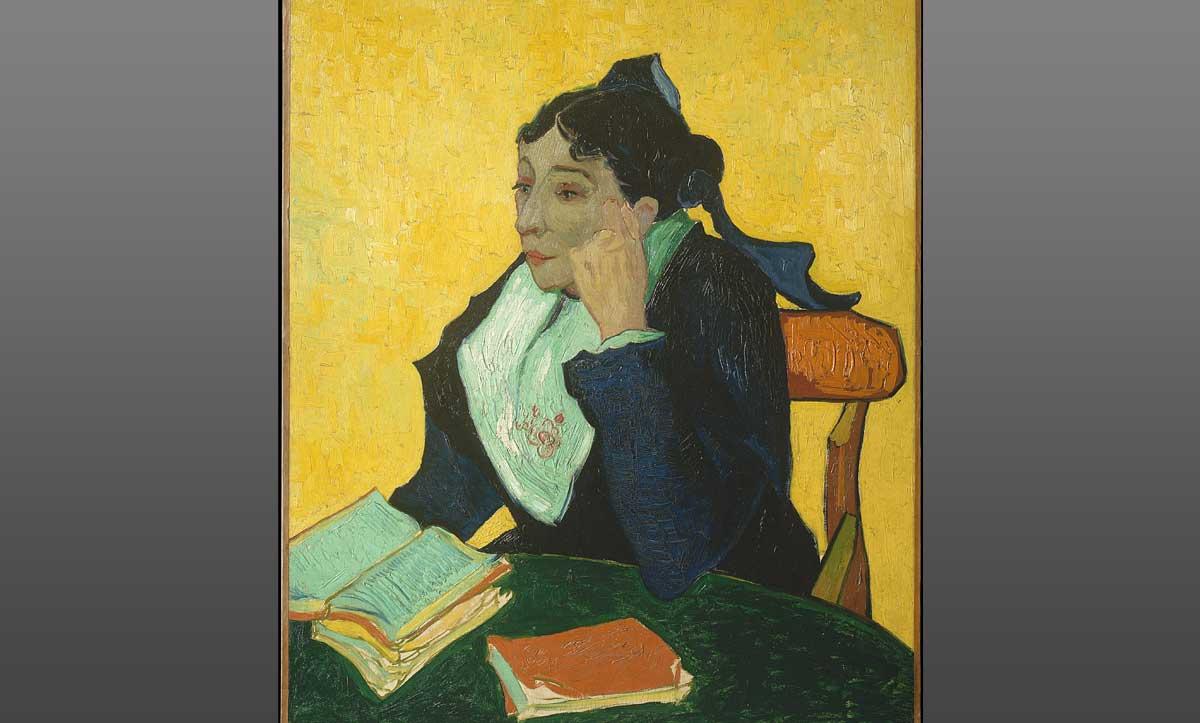

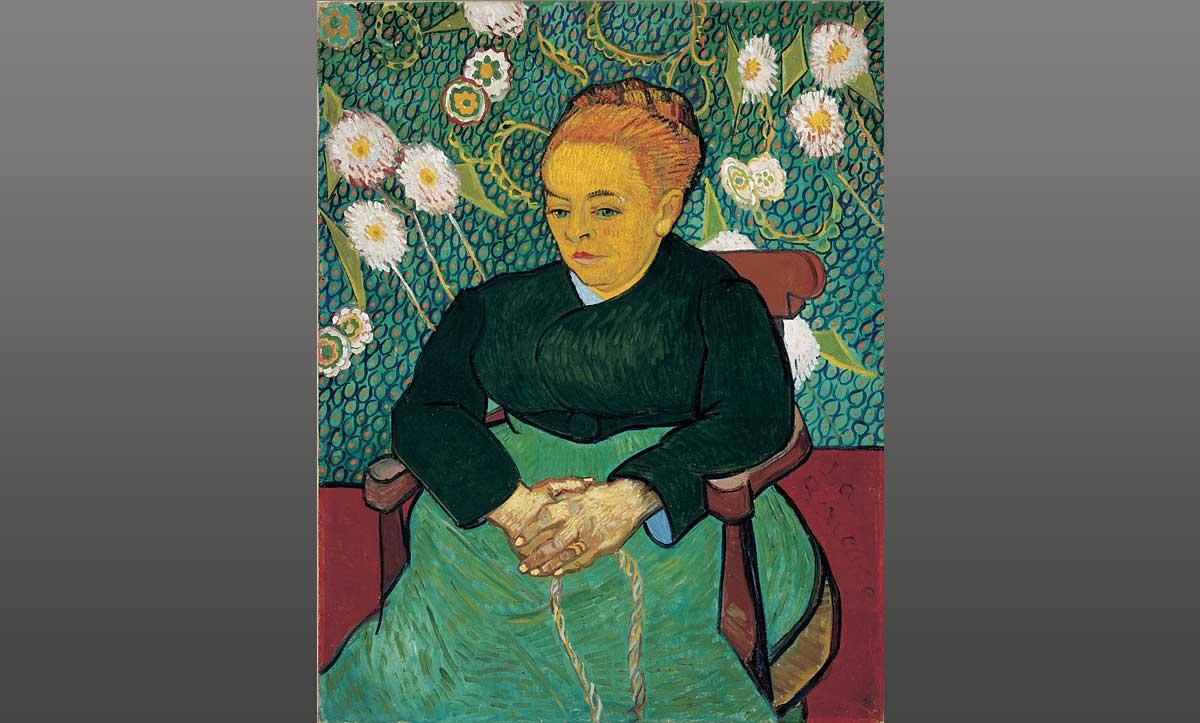

It was the winter of 1886, and a thirty-three-year-old Vincent van Gogh was broke. This was a normal state of affairs for the Dutch Post-Impressionist painter, who leaned heavily on his younger brother, Theo, to pay the bills. What was unusual, though, was that the two Van Goghs were not getting along. And since they were living together that winter, Vincent was in a vulnerable spot.

“He had a bad relationship with his brother at that time,” Louis van Tilborgh, senior researcher at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, said in an interview with Art & Object. “His brother threatened to leave him, so they would separate. And in case of separation, Van Gogh realized that, financially, he would be bad-off.”

The artist urgently sought a way to support himself, in the event that he was left to pay the rent on their shared Parisian apartment at 54 rue Lepic on his own. His paintings, left on consignment with dealers around town, weren’t selling; he needed an alternative plan.

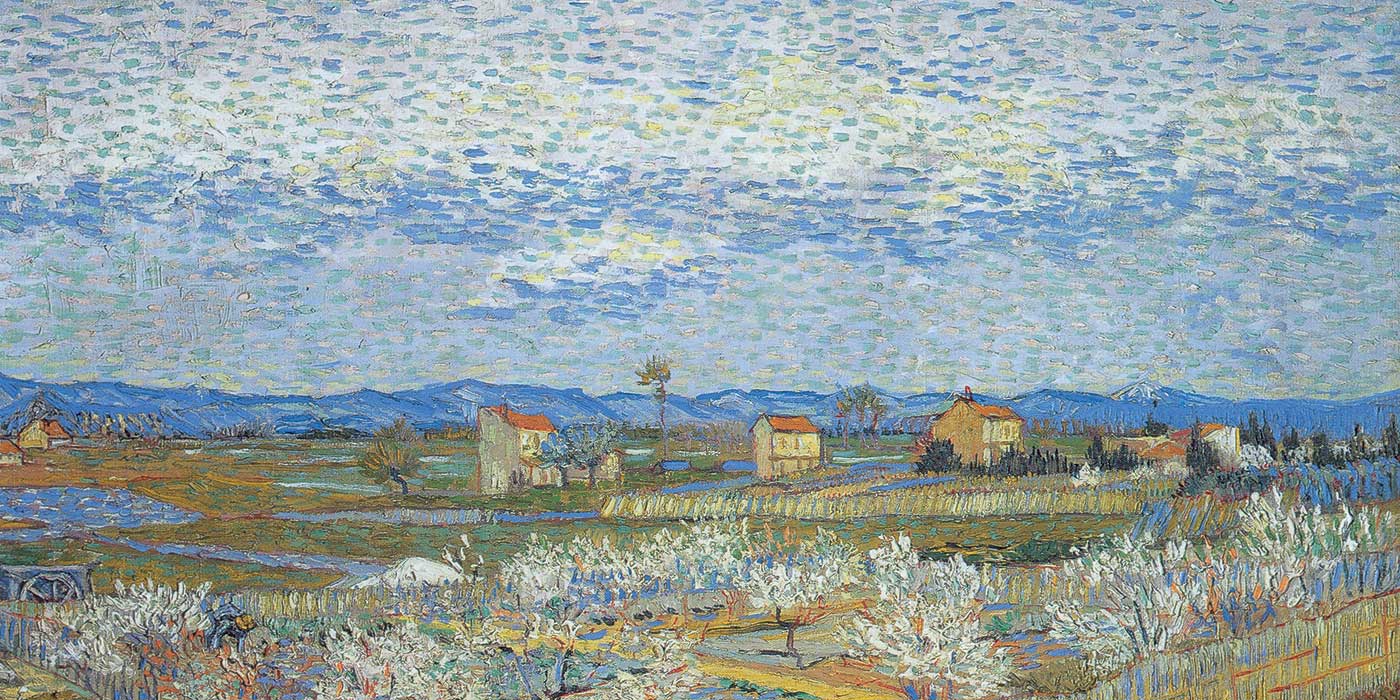

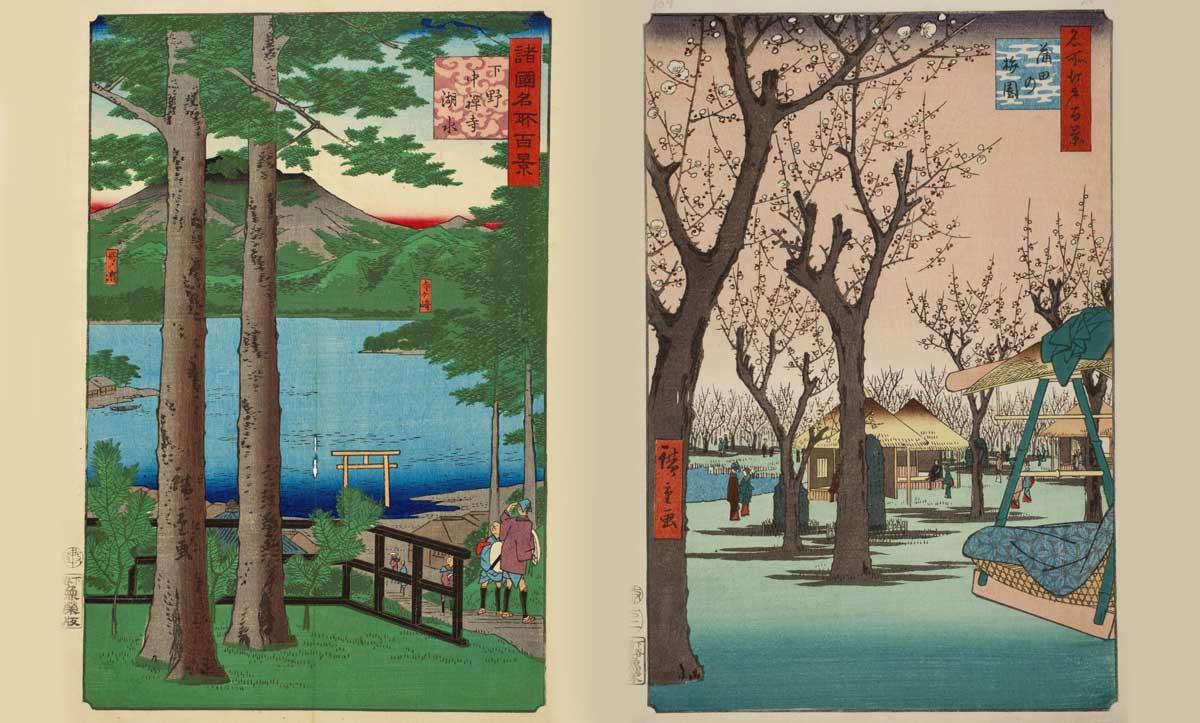

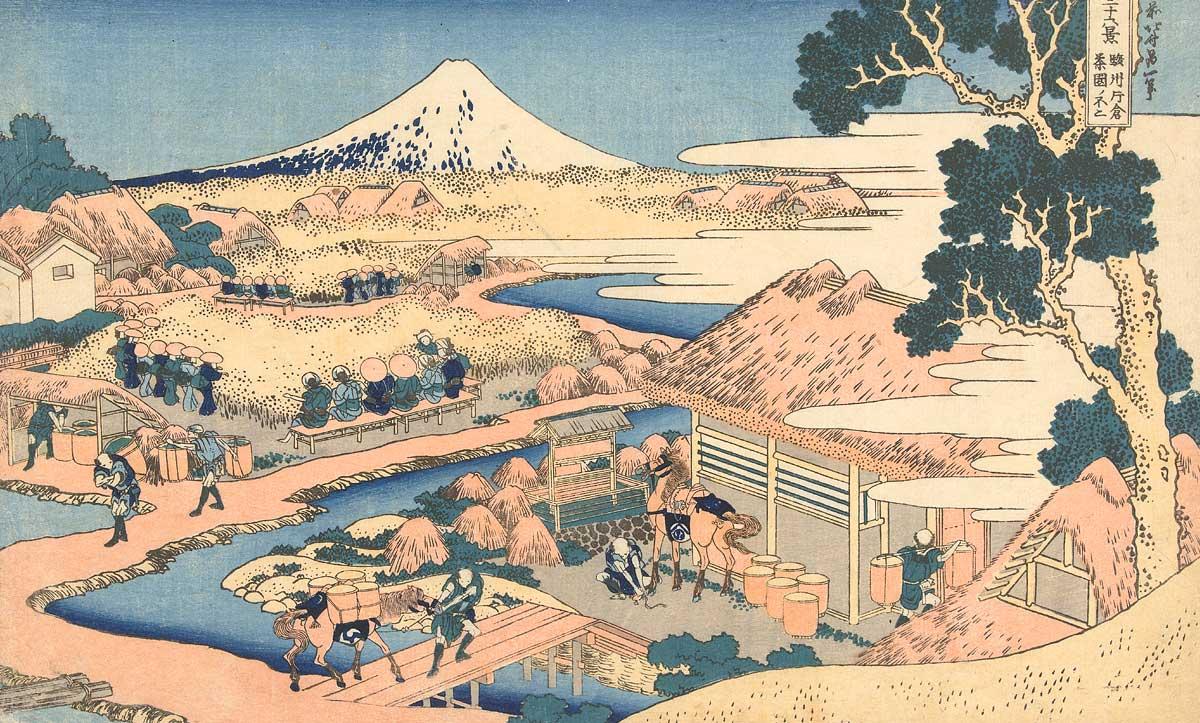

And so, Van Gogh impulsively decided to purchase—and attempt to quickly resell—a bundled lot of 660 Japanese woodcut prints from Siegfried Bing, a veteran and leading Japanese art dealer in the city. This instantaneously acquired assemblage is the subject of Japanese Prints: The Collection of Vincent van Gogh (2018), a scholarly publication that reexamines the artist’s relationship to these prints, which many have long assumed was used strictly for pleasure and artistic study.