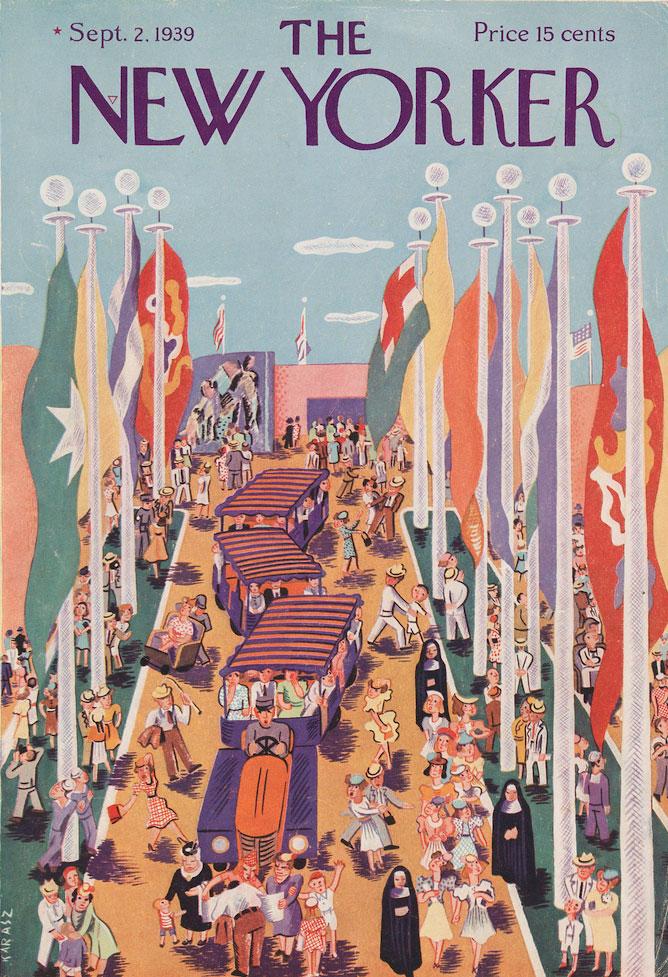

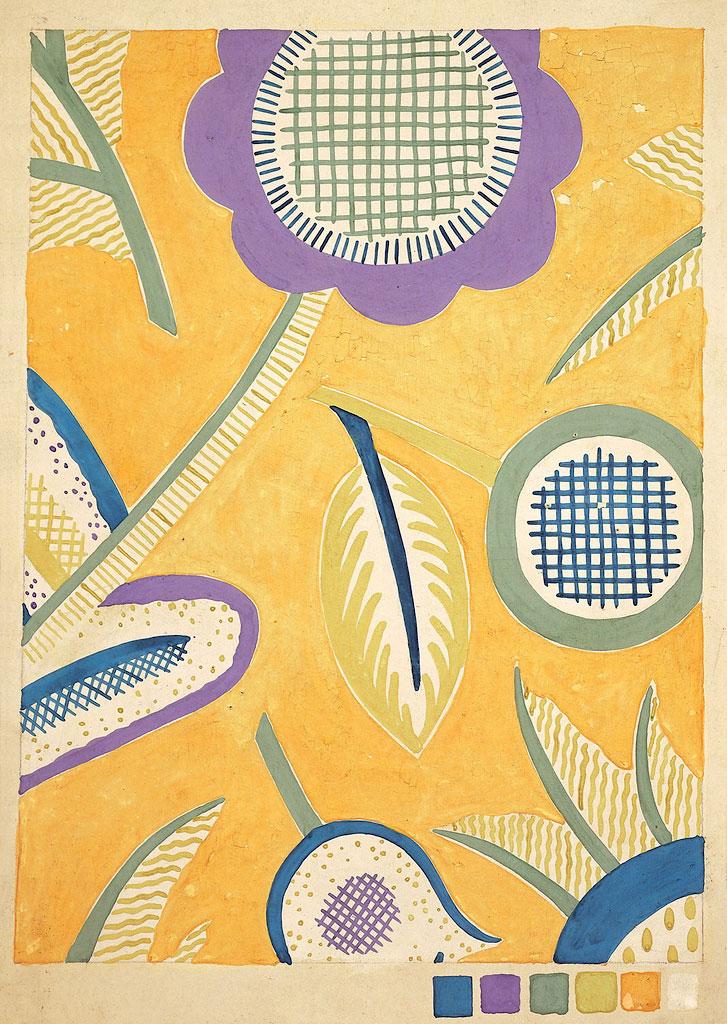

Ilonka Karasz excelled in adapting to the changing trends and new manufacturing processes of 20th-century design, from bringing modernist geometries to silver work and furniture in the 1920s, to earthenware ceramics and pioneering nursery design in the 1930s, to wallpaper with a hand drawn folk art aesthetic in the 1940s. Beginning with her arrival in New York’s Greenwich Village in 1913, until the 1970s, she contributed woodcuts and illustrations to books and magazines, including 186 New Yorker covers. Perhaps it’s this fragmentation of Karasz’s prolific career that has made her legacy obscure.

“She worked for a long time, so there certainly is evolution in her style, but she was consistently modern, emphasizing geometry and simplified lines,” said curator and scholar Ashley Callahan. “She also embraced folk art influences, nature, color, and charm.” Callahan began studying Karasz’s work in 1997 while a graduate student, and when she joined the Georgia Museum of Art at the University of Georgia as its first curator of decorative arts, she organized a 2003-04 exhibition on Karasz and explored her work in an accompanying monograph titled Enchanting Modern: Ilonka Karasz.

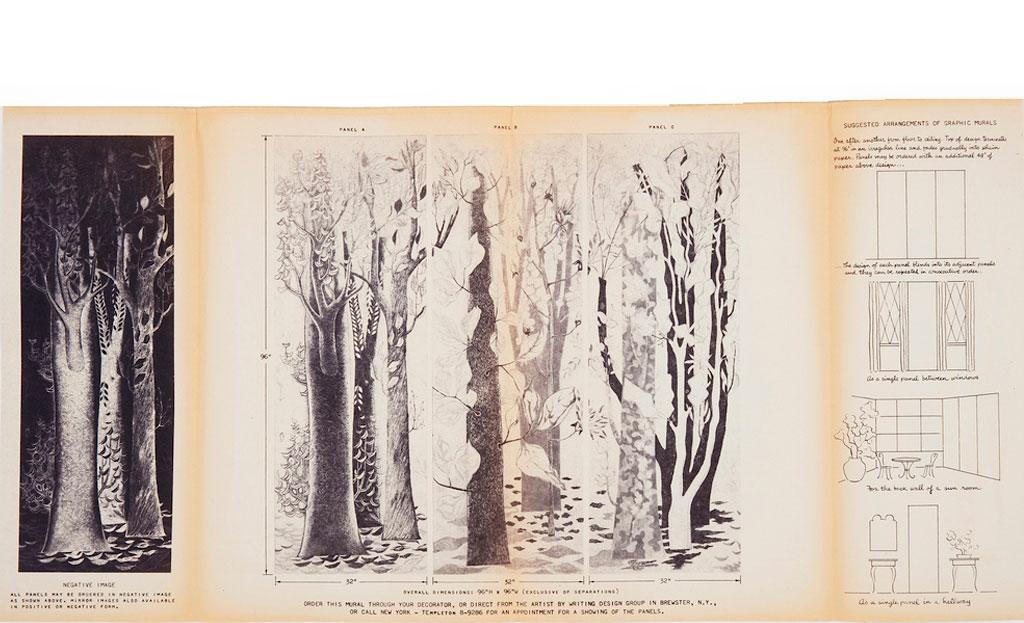

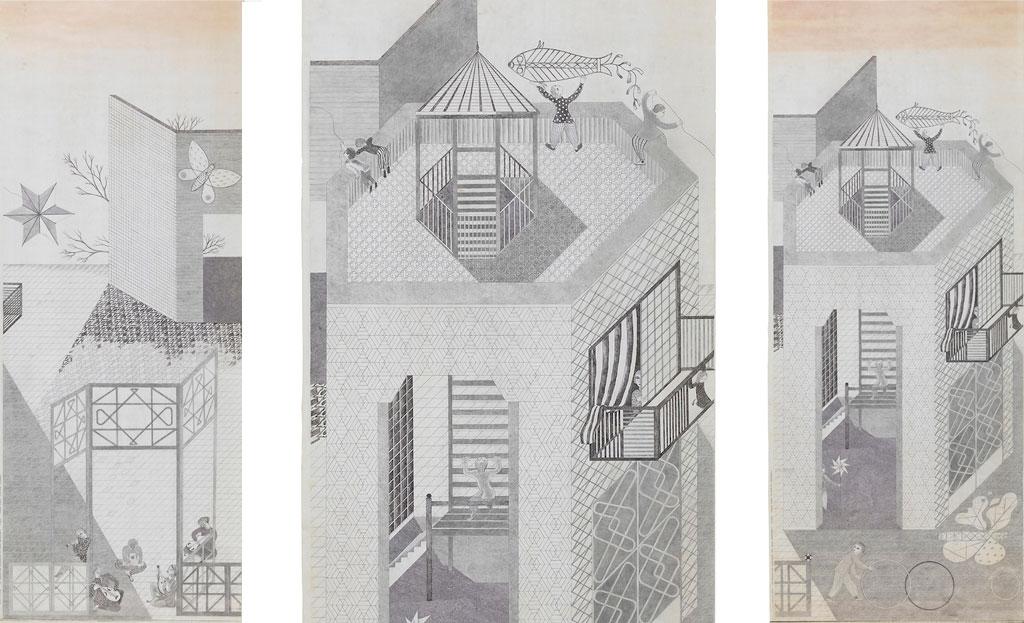

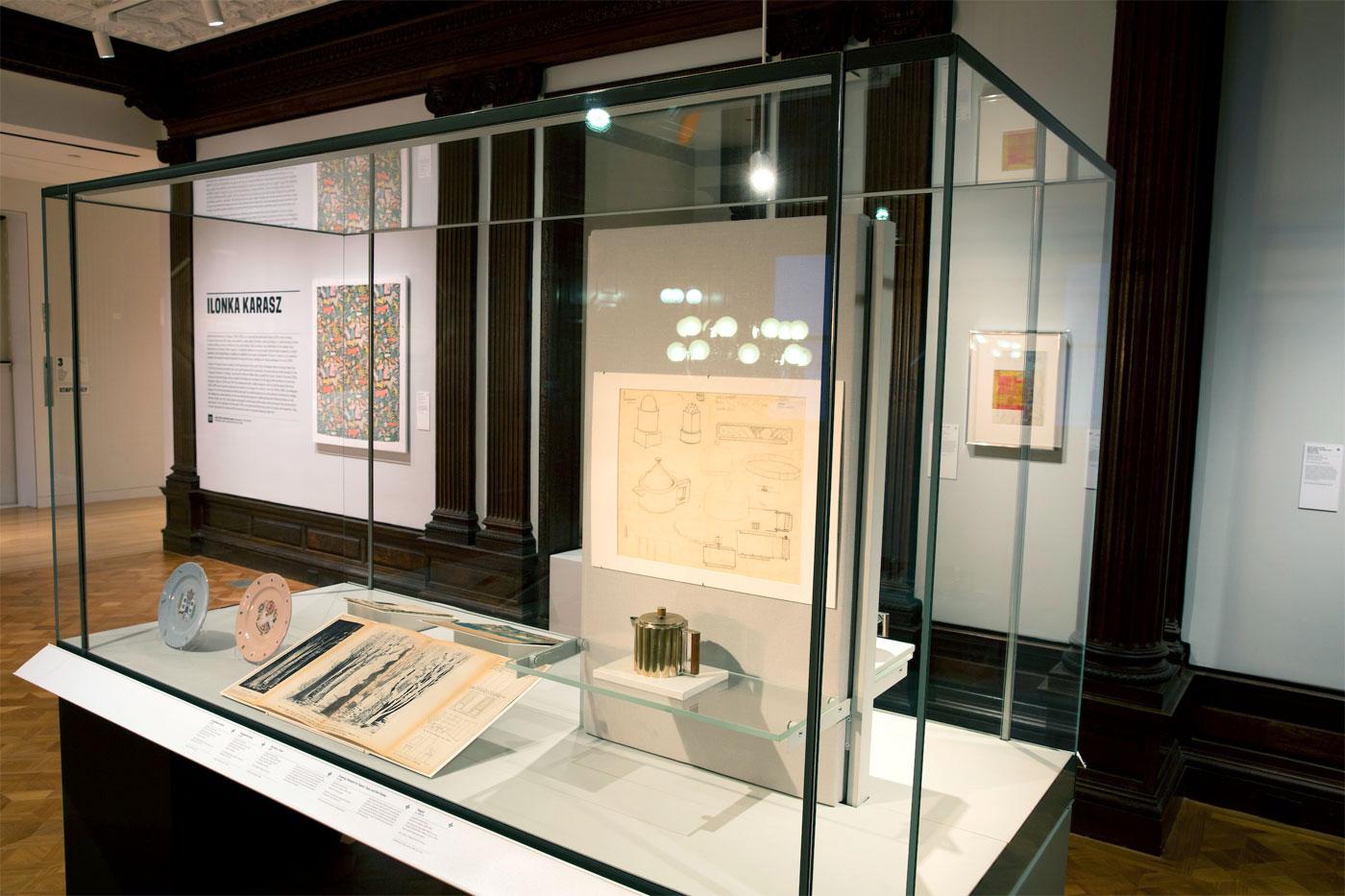

The Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York exhibited almost thirty objects by Karasz in a small 2018 retrospective that visualized her range. “One of the main reasons for doing it now was to celebrate a large gift of her work that we received at the end of last year,” said Greg Herringshaw, assistant curator in charge of the Wallcoverings Department and organizer of the exhibition. “We received a number of her mural wallpapers along with the original drawings for these, which is really amazing. The murals are printed in a technique that required the drawings to be the full scale. So the drawings for these wallpapers are about ten feet tall and all colored with graphite and ink.”