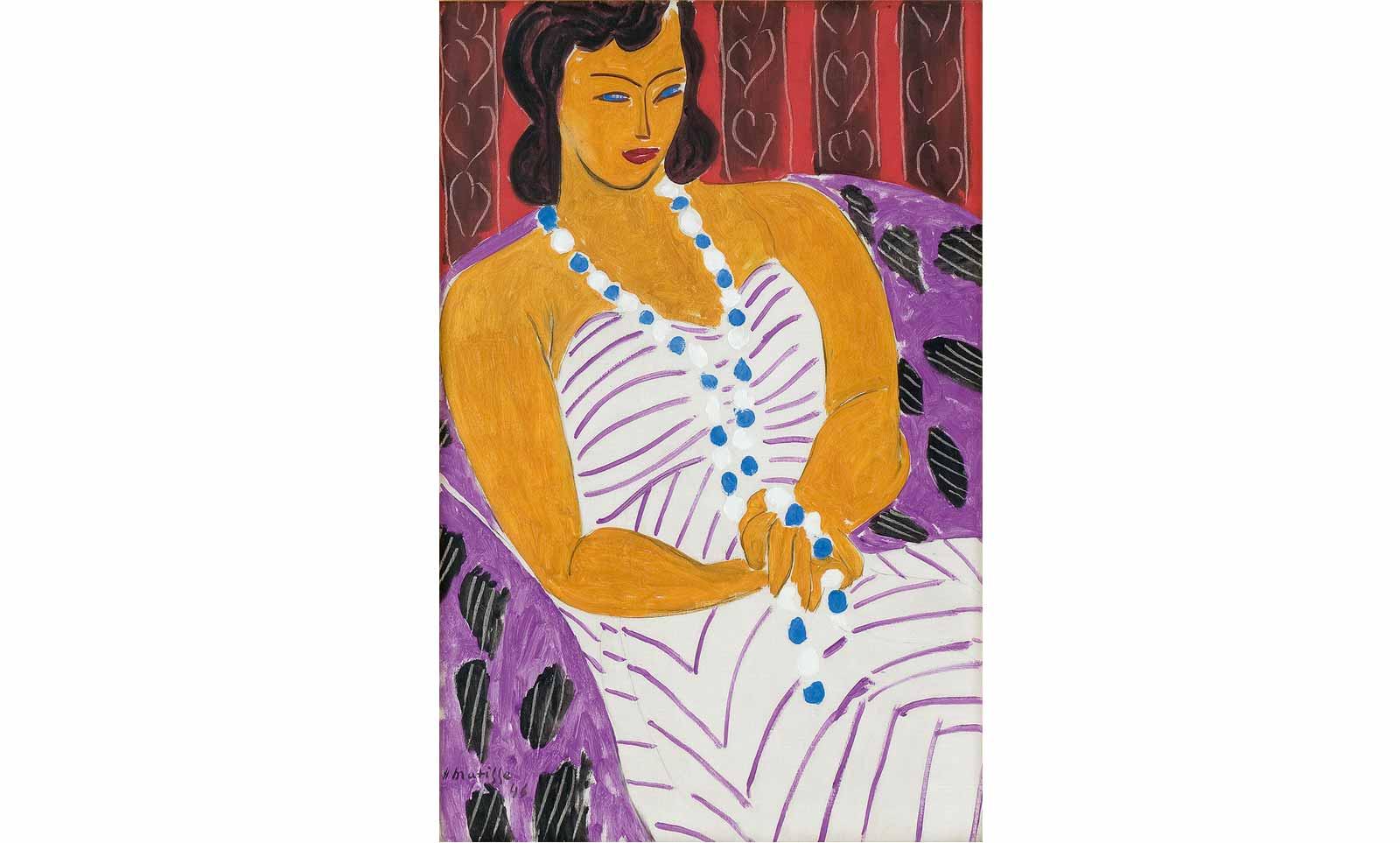

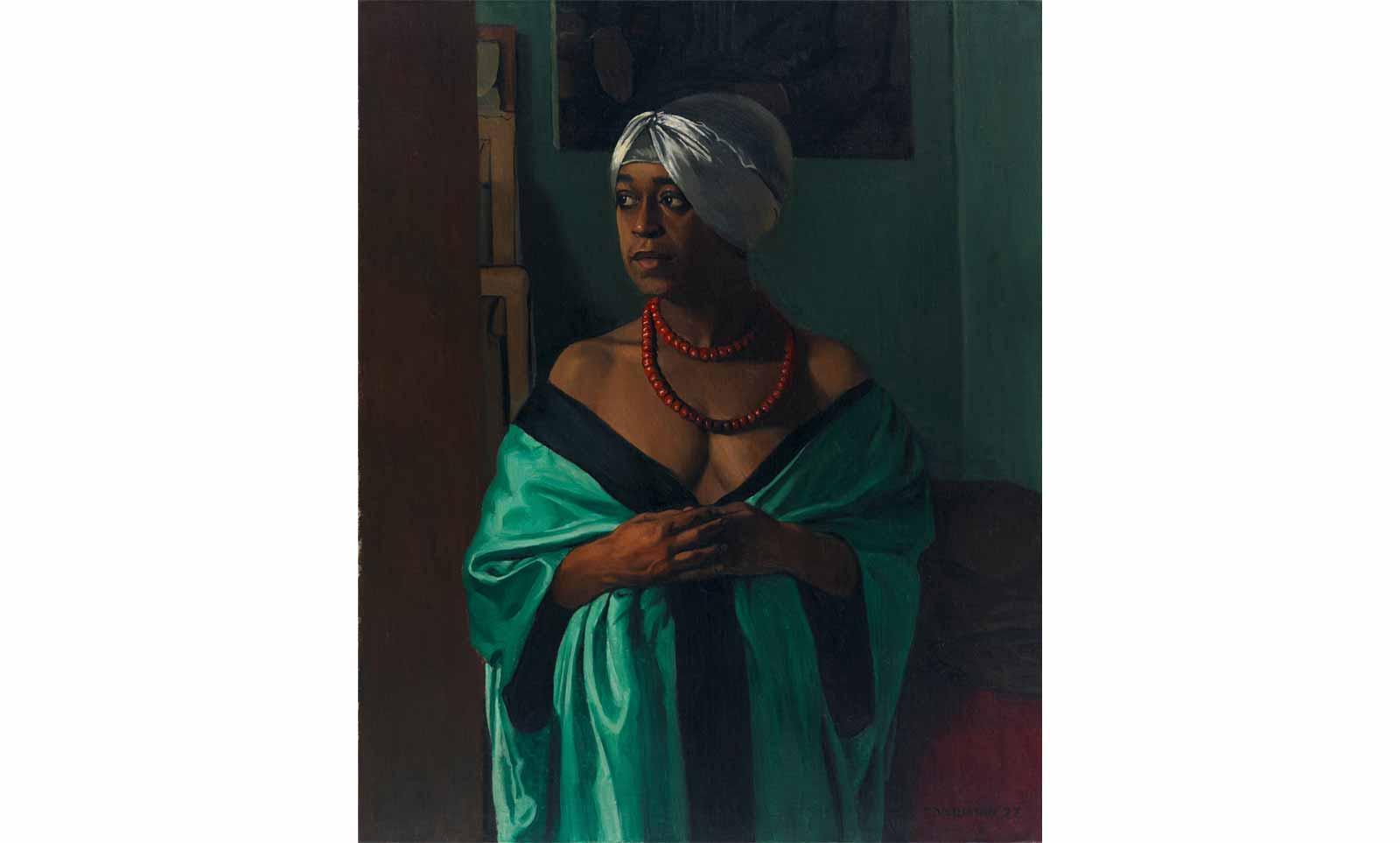

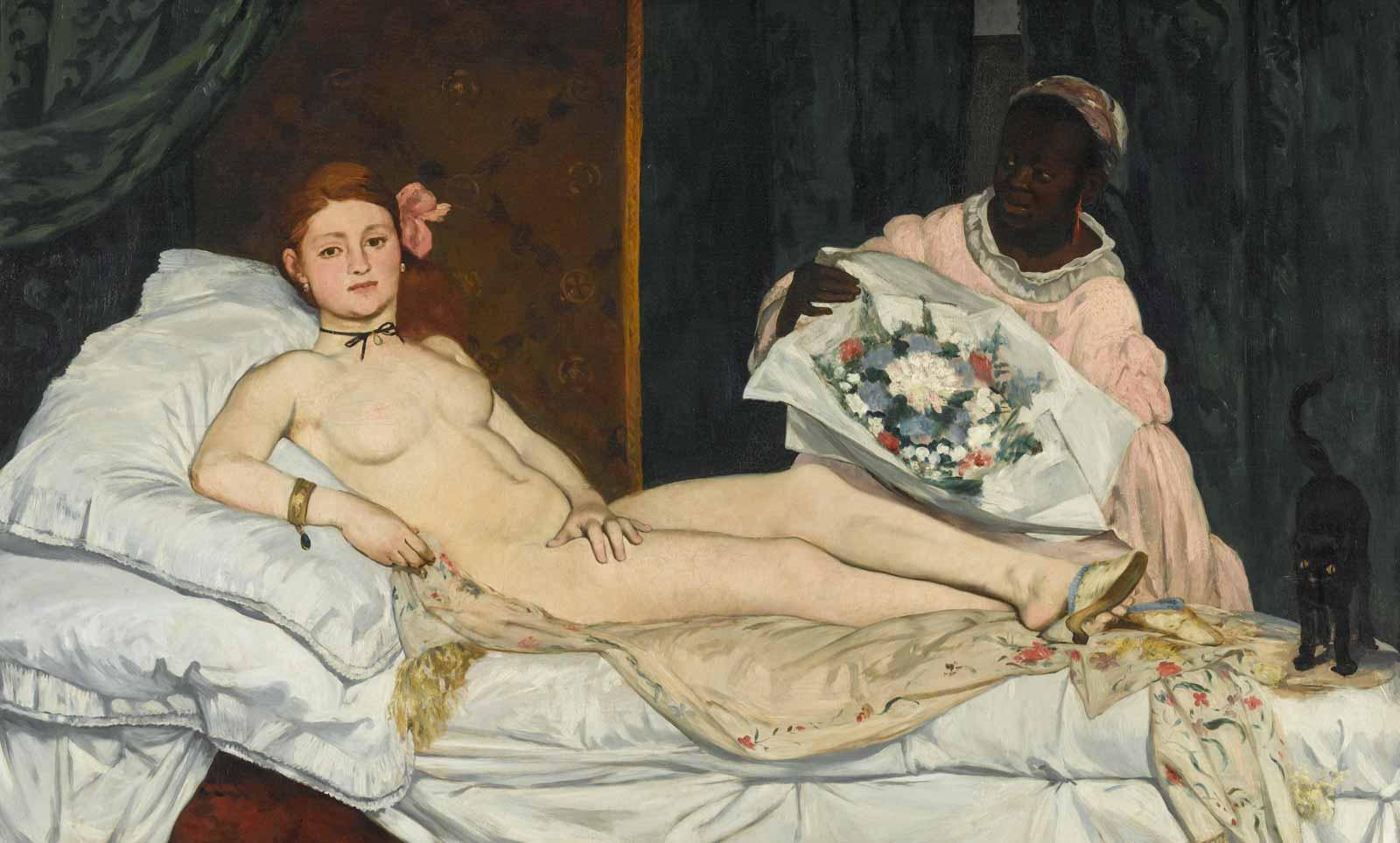

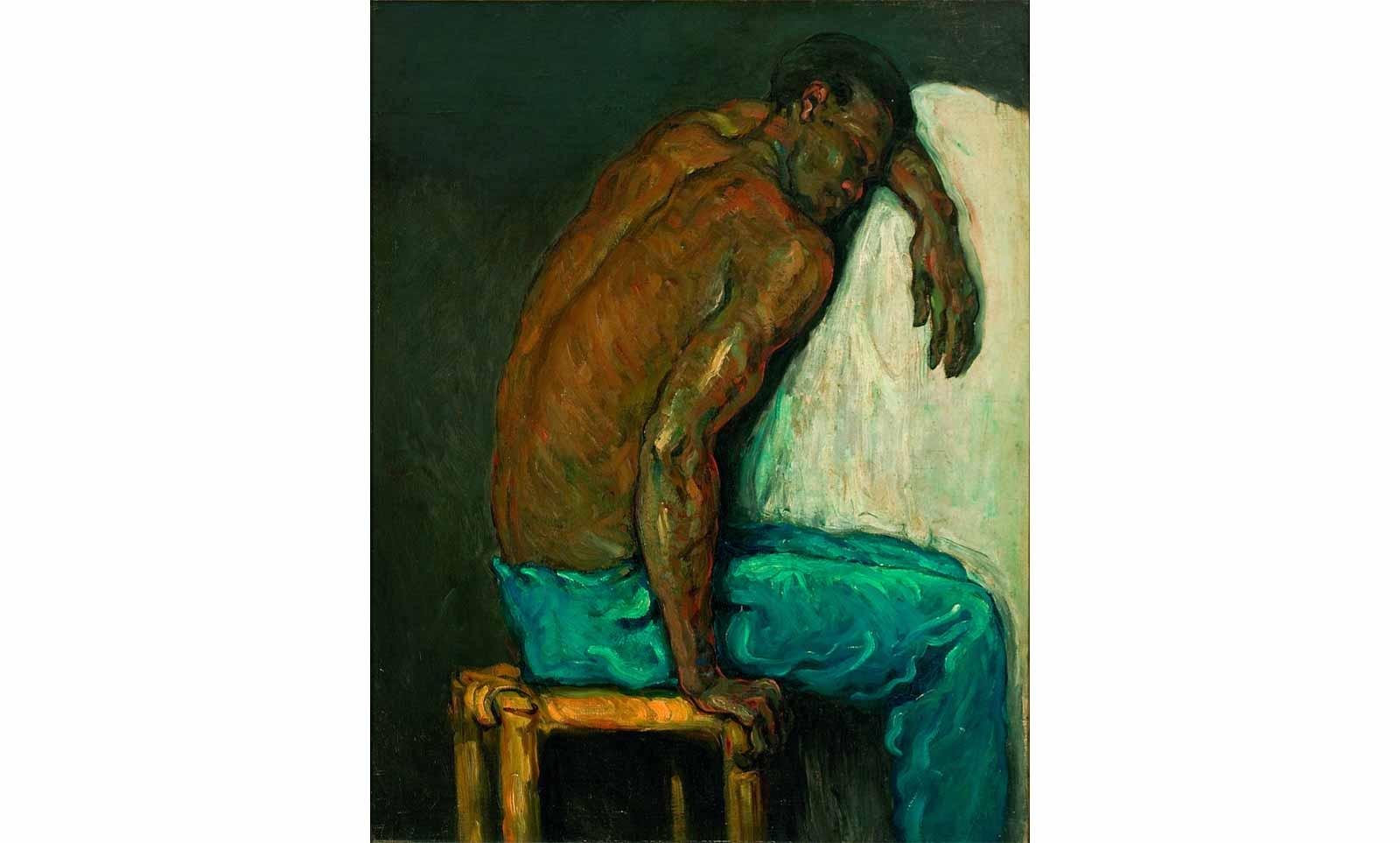

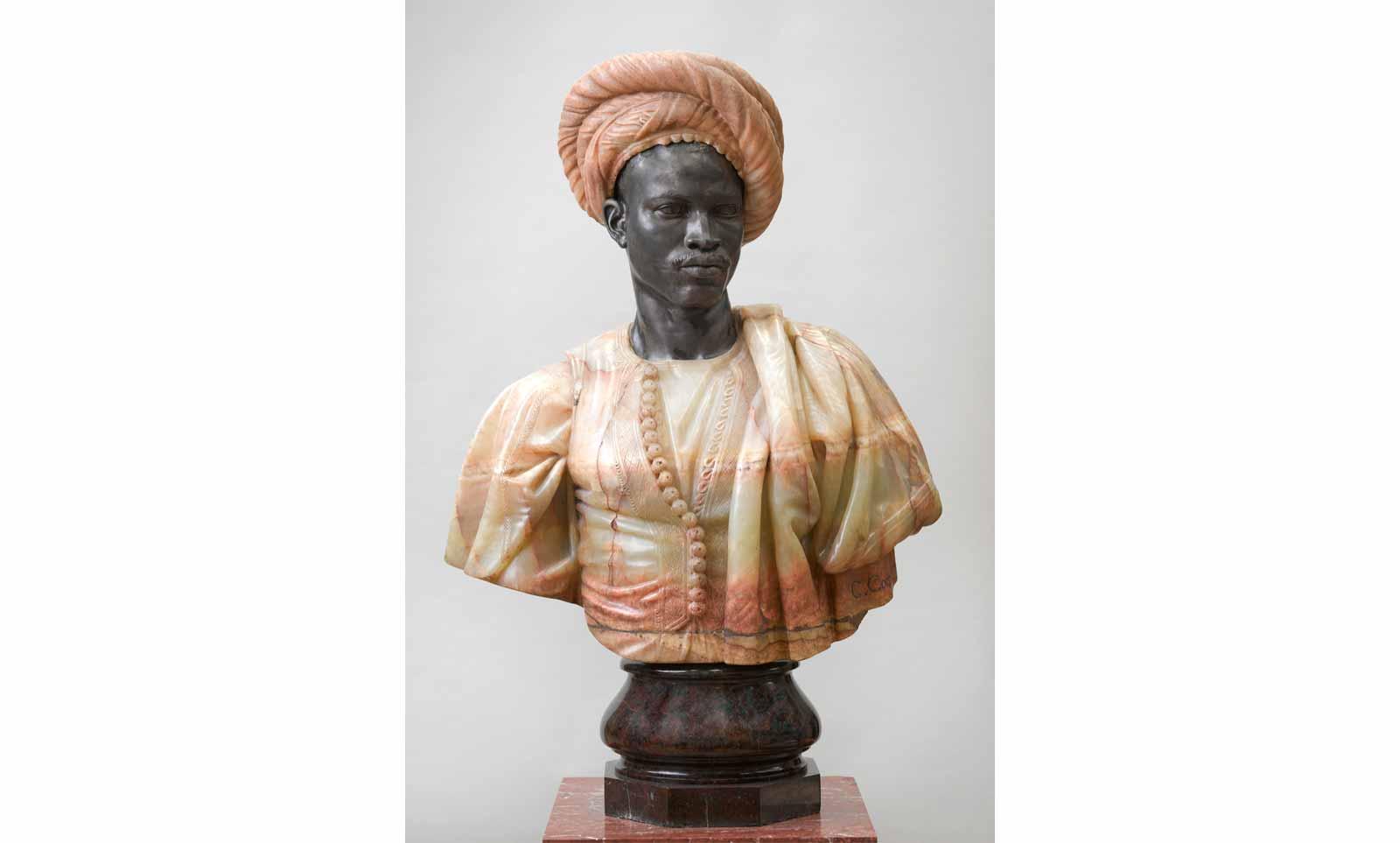

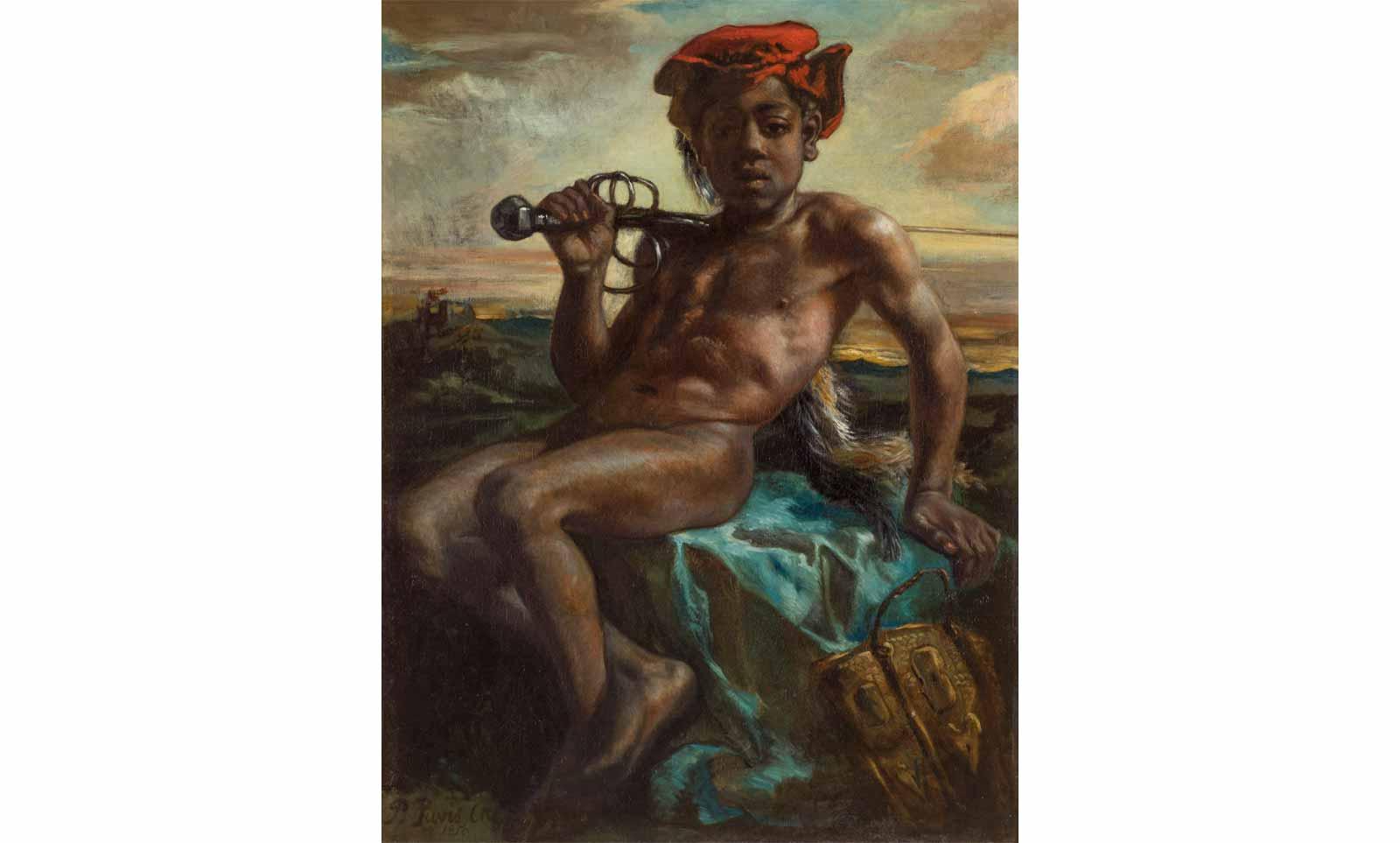

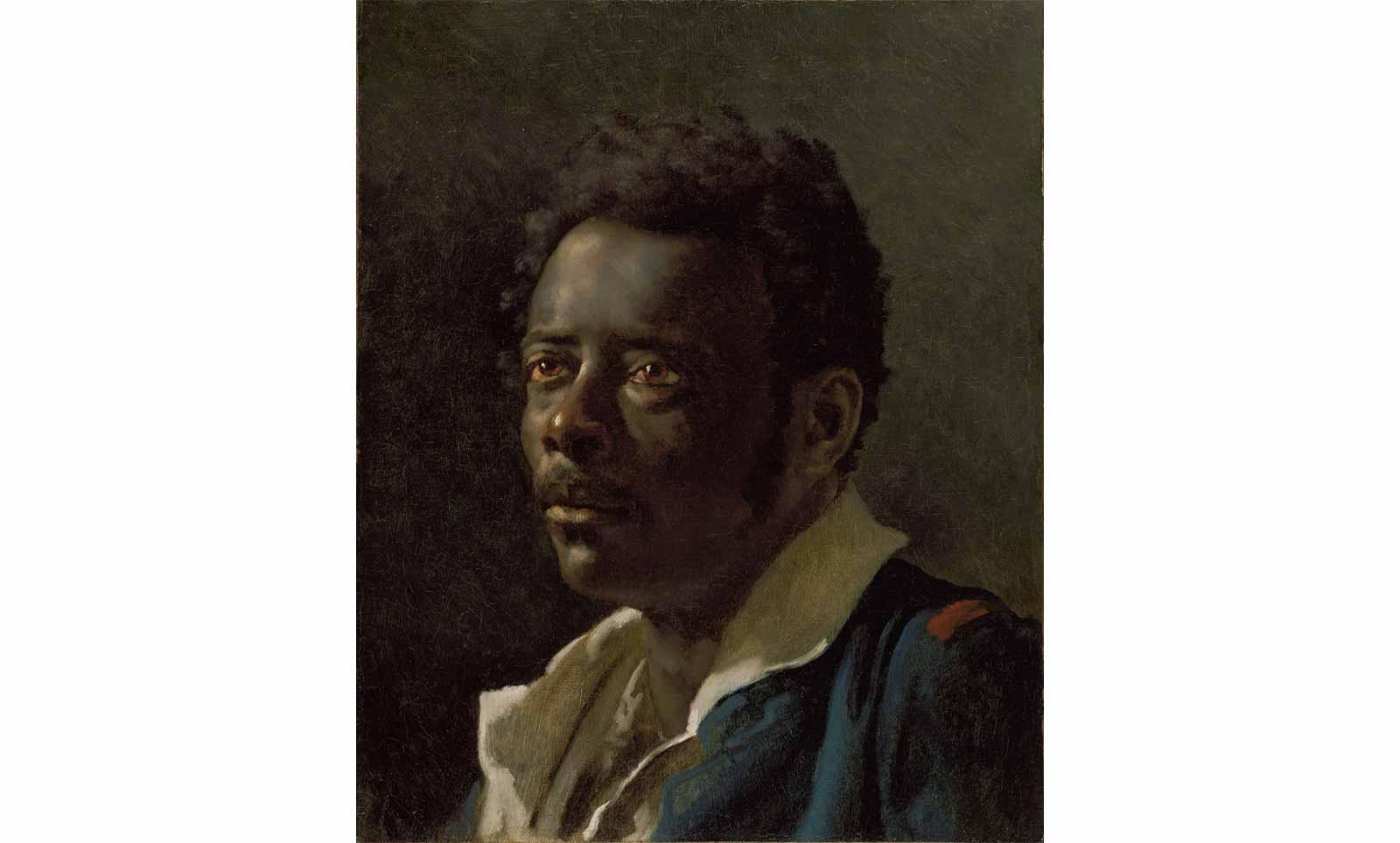

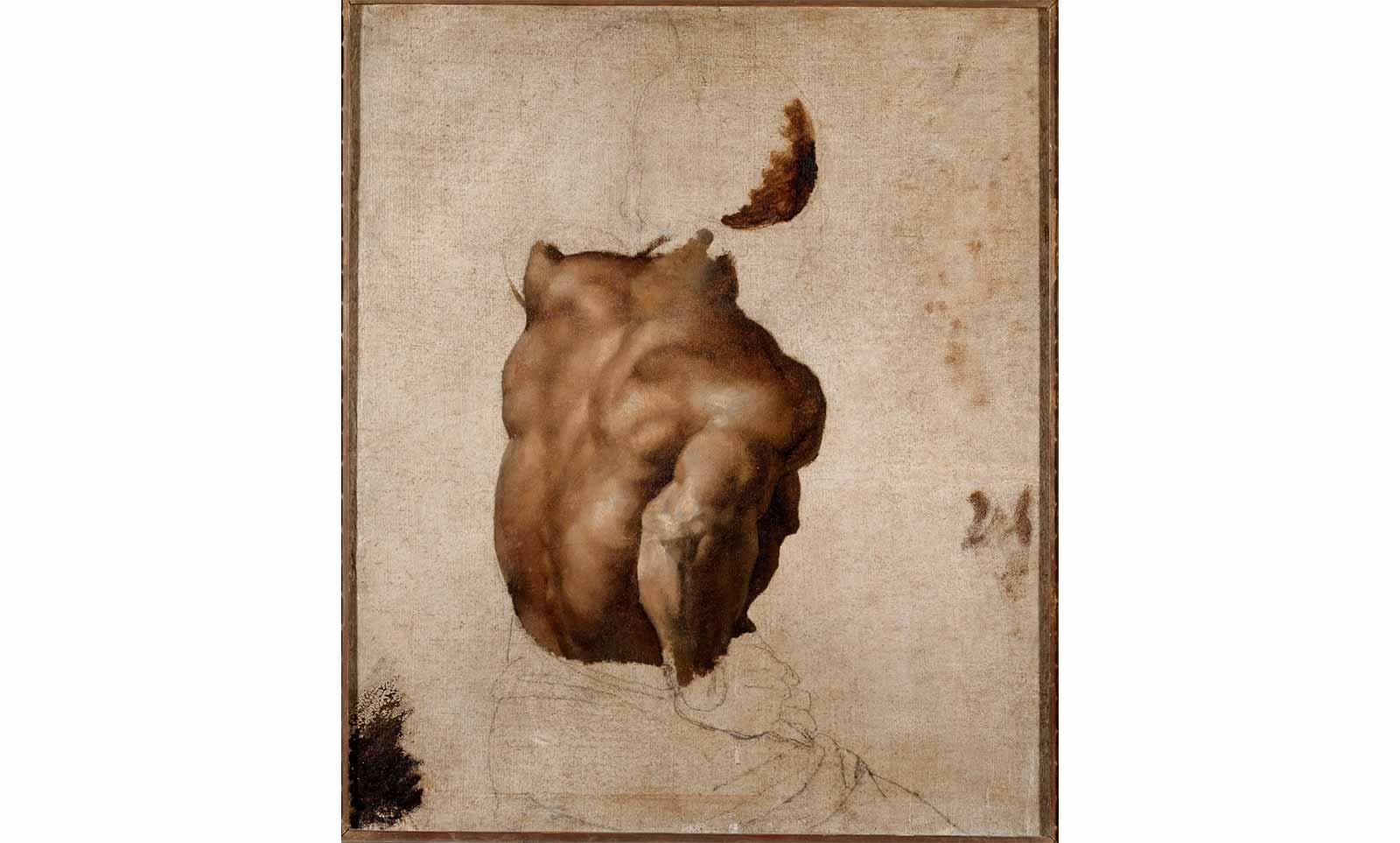

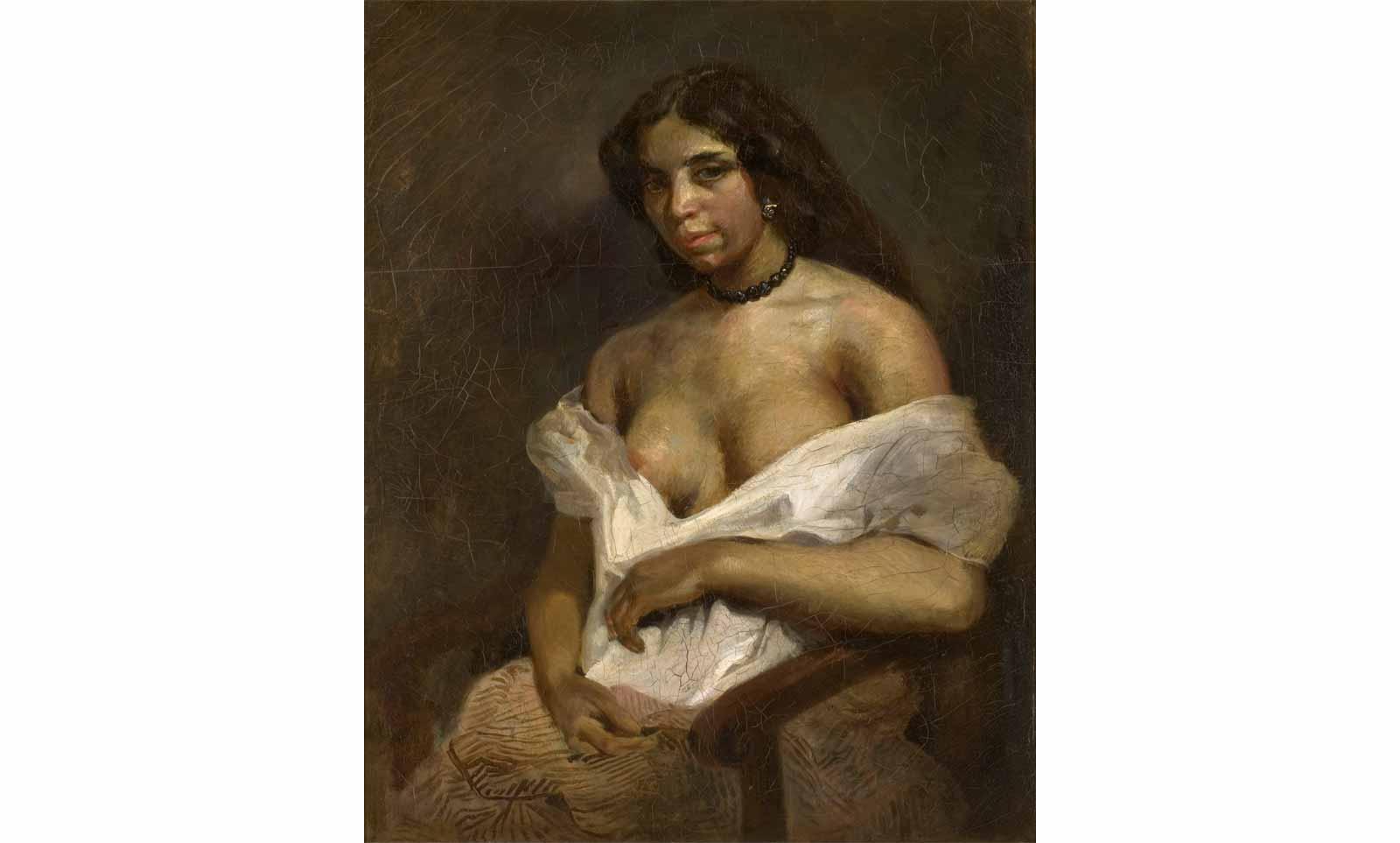

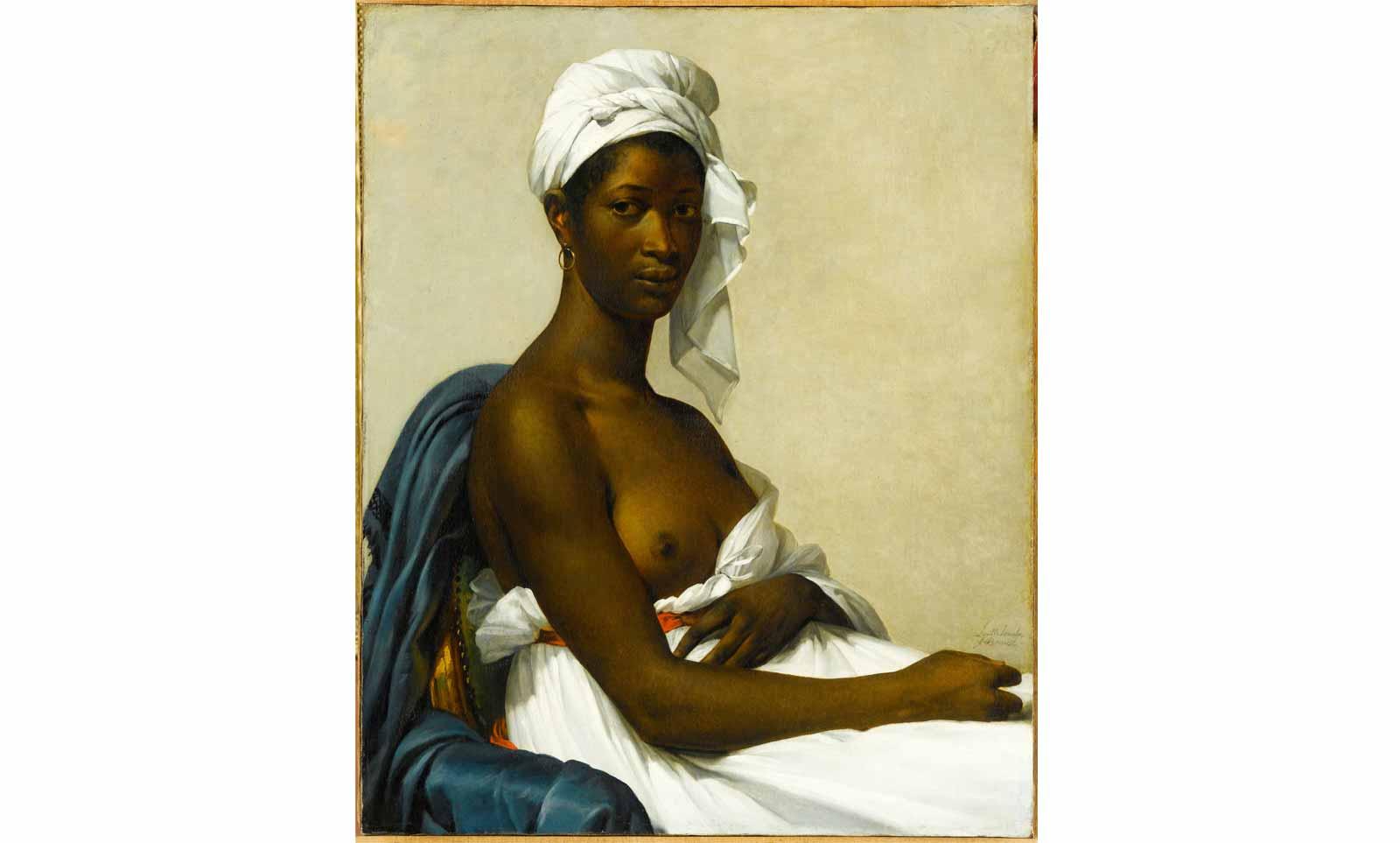

In organizing Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today, which ran October 24, 2018 to February 10, 2019 at the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery at Columbia University in New York, curator Denise Murrell aimed to shift visitor perceptions of black figures in the presented artworks, down to their label text. Many of the titles referred to subjects solely by their race, and Murrell wanted to find their names.

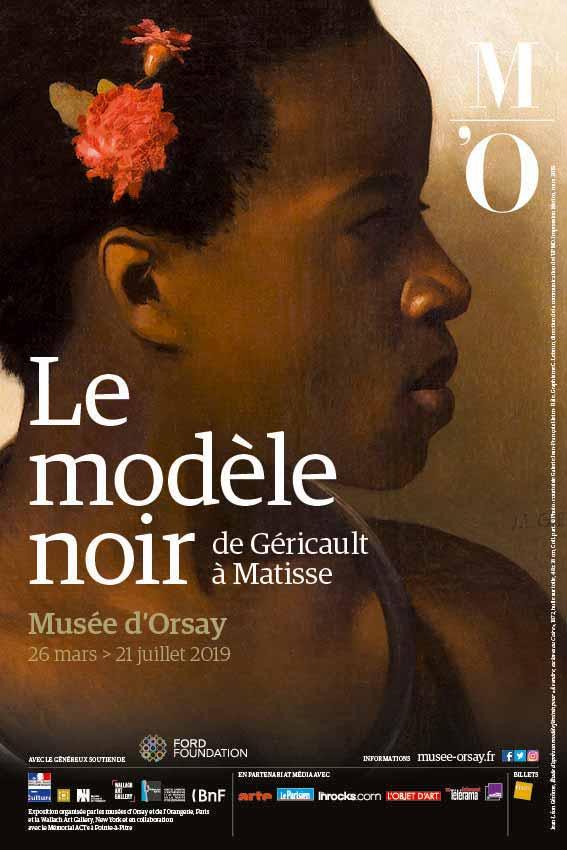

"We were talking about some of the titles of the works in the Wallach, and Denise said she really wished she could change the titles, but we couldn't because the lenders have a legal right to say what the label is going to be like," said Anne Higonnet, professor in the Department of Art History and Archaeology at Barnard College and Columbia University, who worked with Murrell on her research at Columbia. When the exhibition expanded into a larger show at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, the museum’s director Laurence des Cars supported the idea, and with that backing several works were temporarily retitled for Le Modèle noir, de Géricault à Matisse, on view through July 14, 2019.

“The politics of this are evident in the poster for the exhibition and the cover of the catalogue and also in the opening invitations,” Higonnet said. “The Orsay elected to choose all works that they were changing the titles of, and they included the title change and the old title to point out that it used to be different."