Kinngait, a village formerly known as Cape Dorset, is one of Canada's most important artistic centers. The arctic community, its arts cooperative, and art studios are located on Dorset Island, off the southwest coast of Baffin Island in Nunavut. Though its population sits just under 1500, a significant portion of the village's residents are working artists. Kellypalik Etidloie, Saimaiyu Akesuk, and Killiktee Killiktee are three Kinngait artists whose work has begun to achieve international acclaim. Interviews with the three multimedia artists offer a glimpse into the vibrant contemporary arts scene in Kinngait.

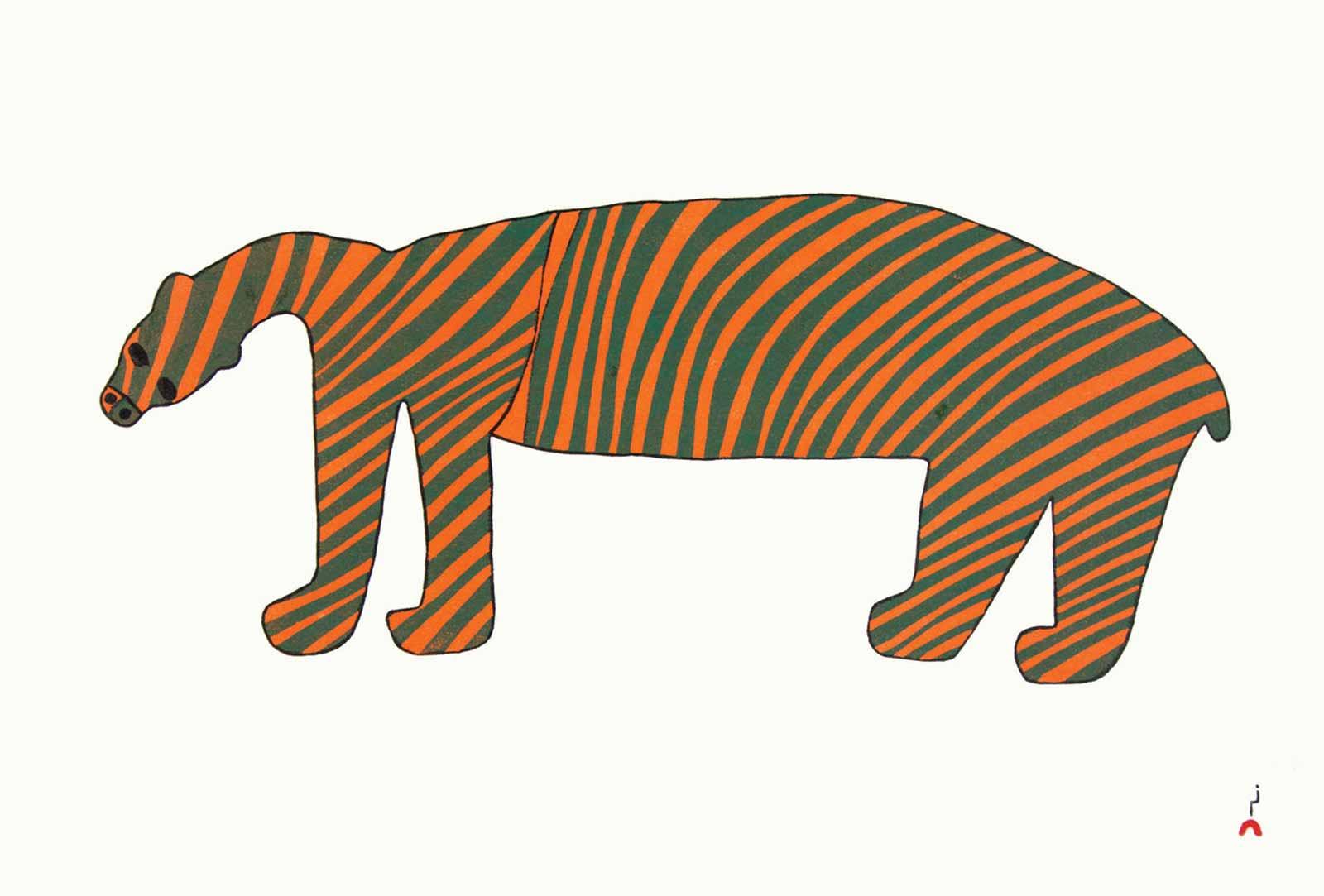

The works that artists are producing in Kinngait are dynamic, varied, and difficult to encapsulate in writing. Yet exhibitions in southern Canada have too often silenced or reinterpreted Inuit artists' voices in an attempt to market their pieces to outside audiences. In more recent years, many Nunavut artists are gaining international recognition, and collectors and viewers are becoming more attuned to the specificities of each artist's work. While Kenojuak Ashevak, one of the first generation of Kinngait printmakers, is often cited as the most well-known artist from the region (with many of her pieces in collections at the National Gallery of Canada, the Art Gallery of Ontario, and even on Canadian postage stamps), a new generation of artists are now establishing far-reaching reputations for their work.

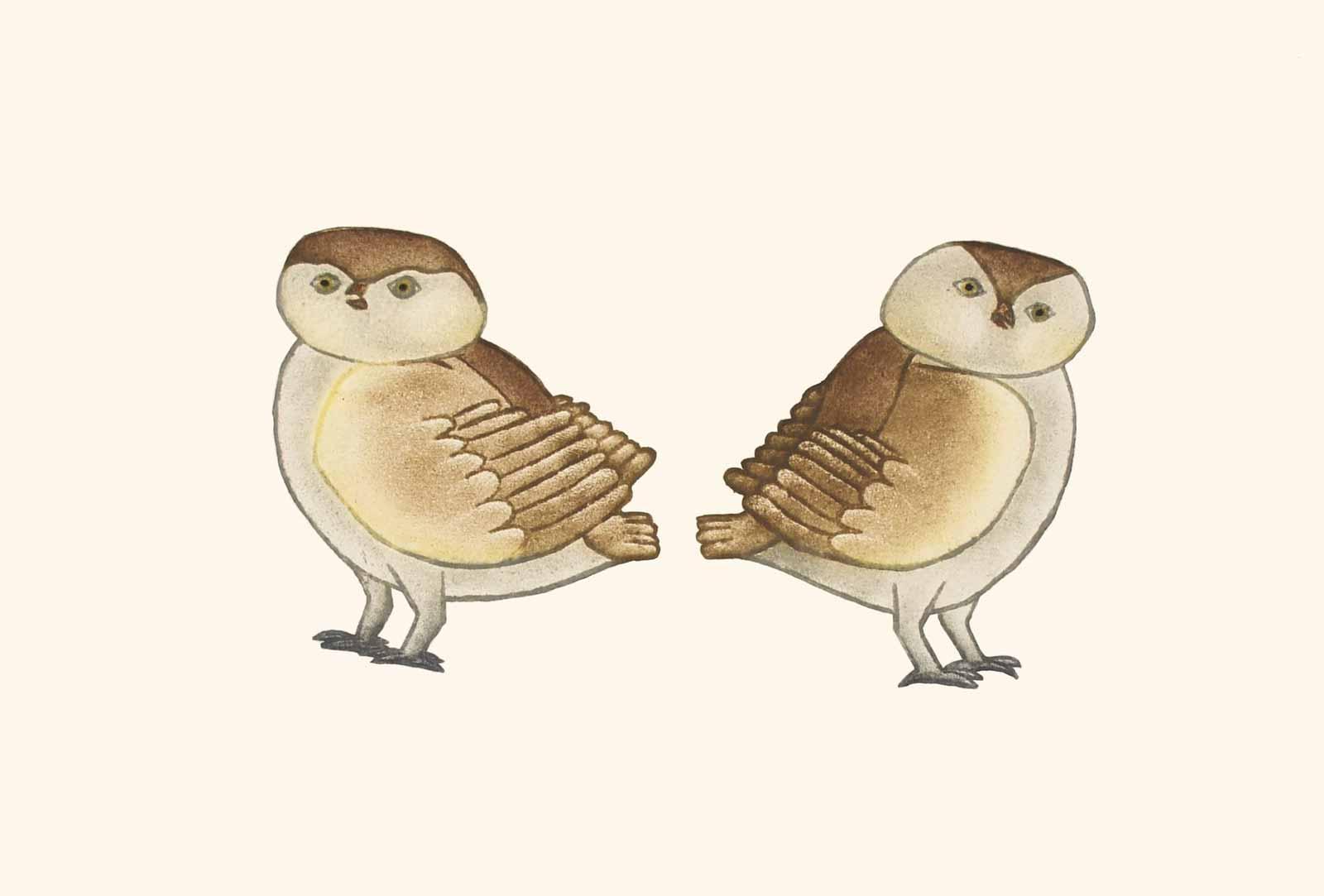

Commercial considerations are important to the artists currently working in Nunavut. Kellypalik Etidloie is a carver who produces dynamic, anthropomorphic animal carvings that appear to move, seemingly emerging from the stone from which he carves them. Etidloie comes from a long line of artists and feels a strong connection to his family when he carves. He says that much of his practice is inspired by the materials with which he works. For Etidloie, the most important aspect of his practice is persistence: he works every day, and this consistency has necessitated inevitable change in his practice.