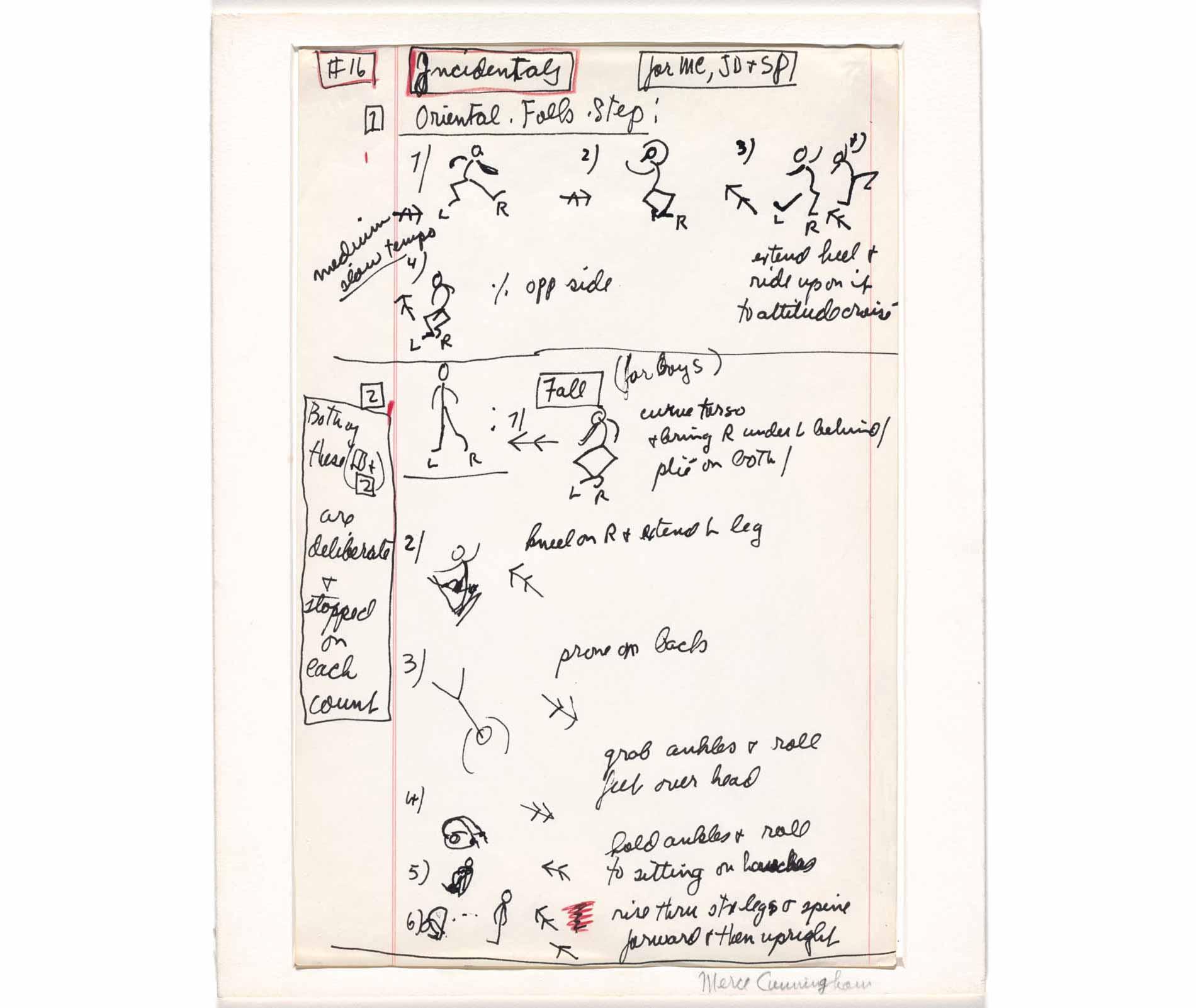

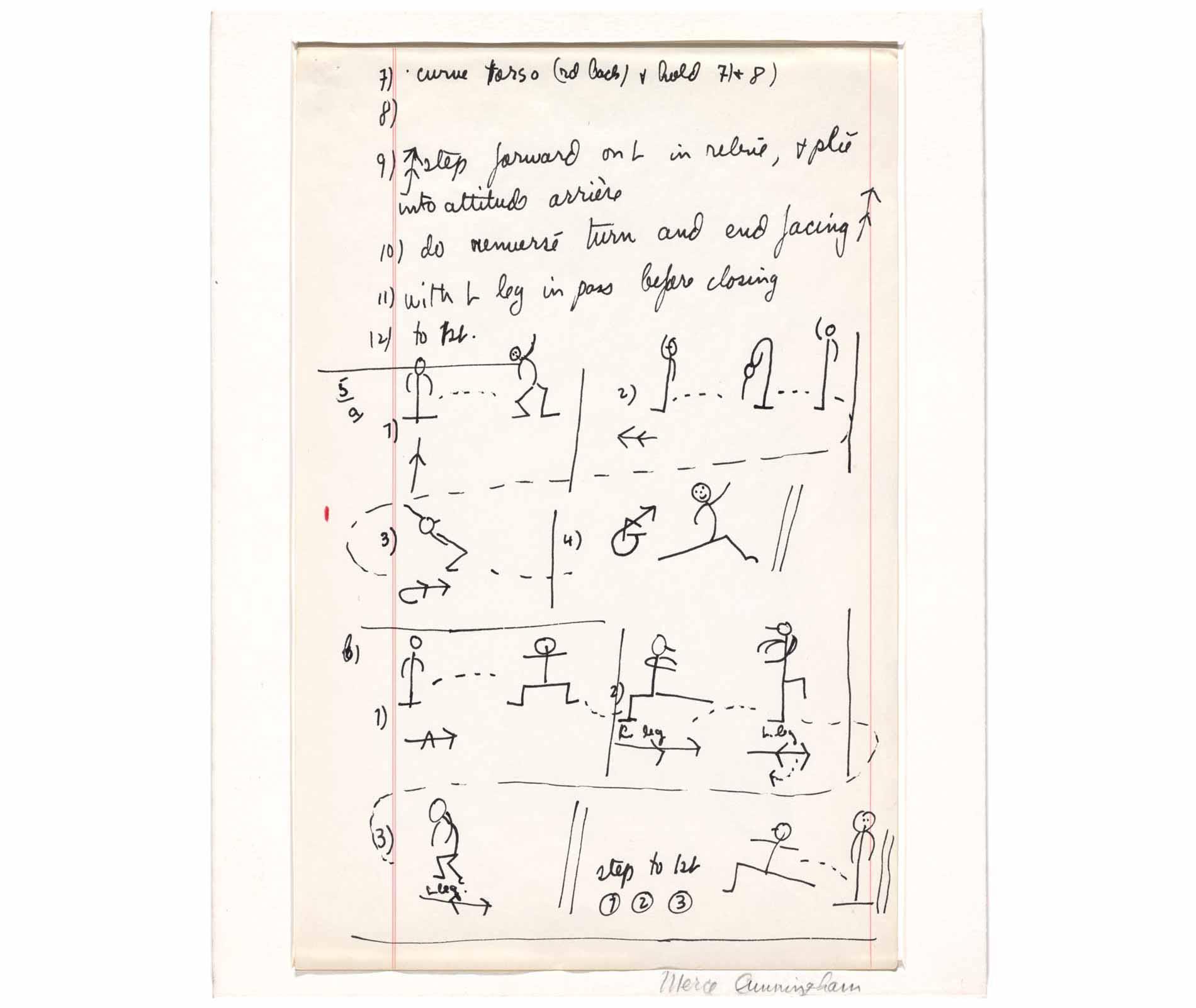

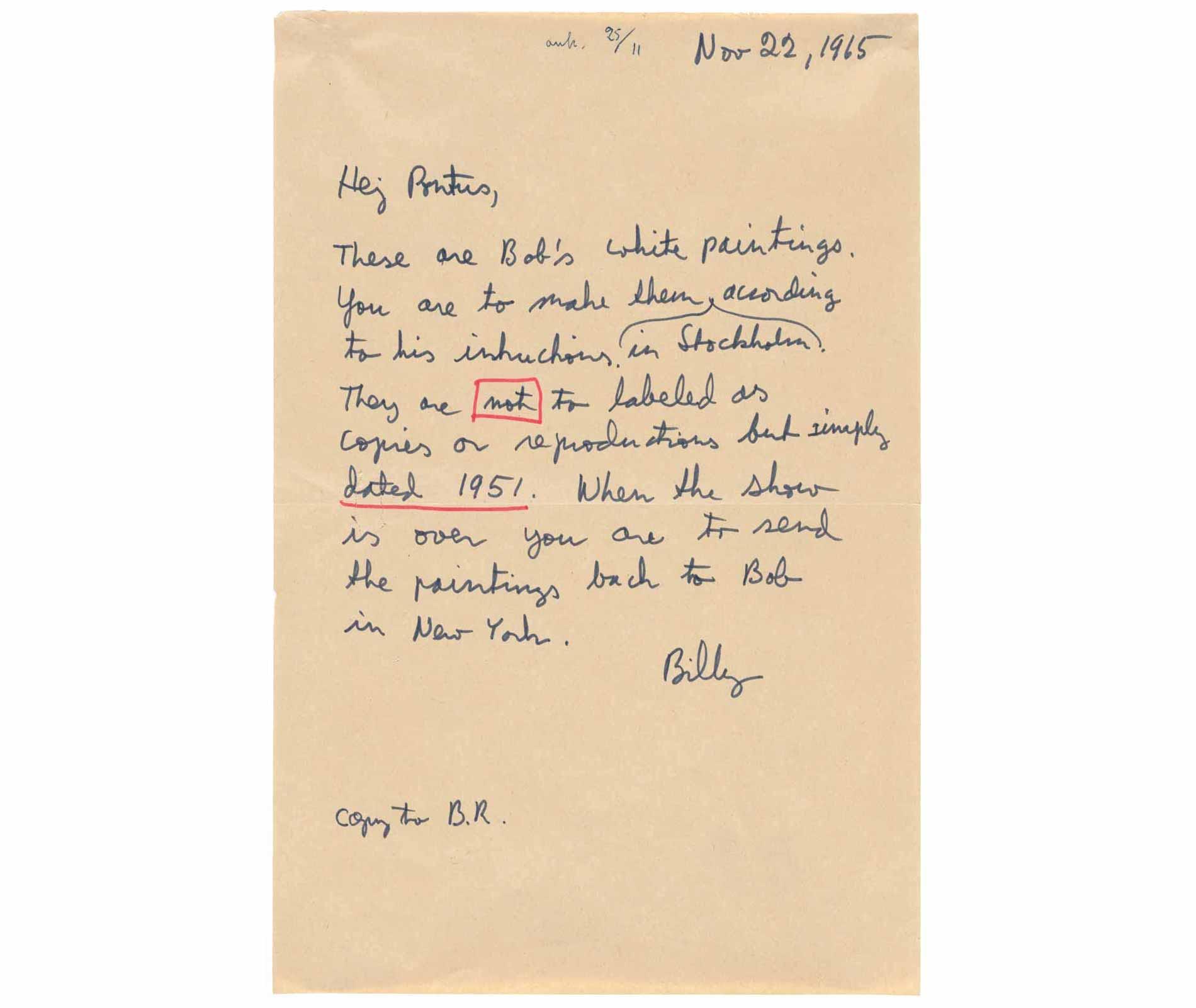

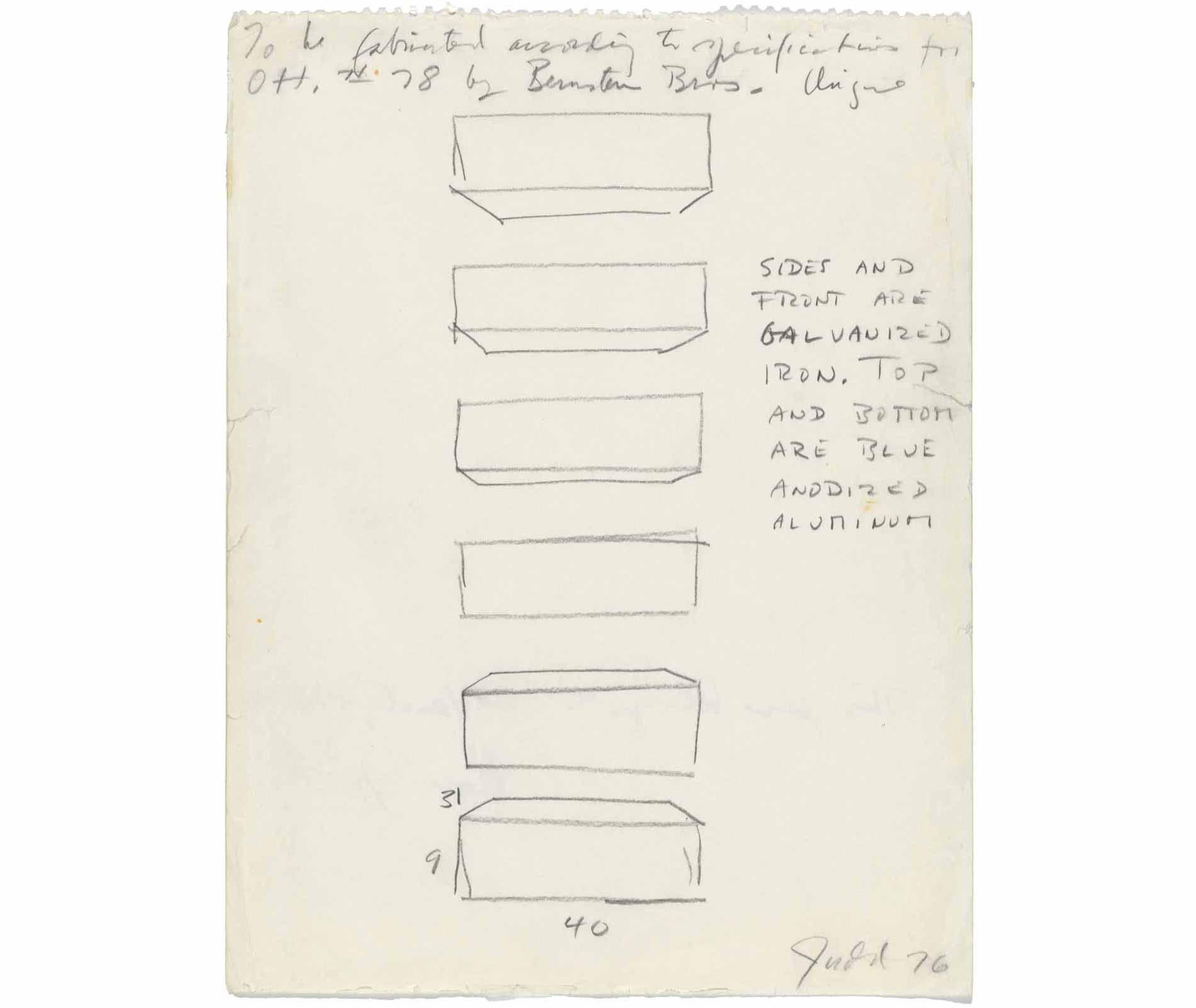

In late January 2019, New York’s Museum of Modern Art announced a notable bequest from Gilbert B. and Lila Silverman: a lot of 800 drawings by more than 300 different artists. More than 100–113, in fact–are works by artists new to the MoMA roster. These are no ordinary drawings, though, nor are they out of keeping with the Silvermans’ other donations. They contributed a major collection of Fluxus art and the archives of Avalanche magazine, which privileged the artist’s outlook over that of critics. These new drawings are instructional drawings. In short, they account for the how and why behind an exhibition’s installation (whether or not there was an exhibition, in the end). What eventual end the drawings will be put to is for now pure speculation, albeit speculation that offers rich possibilities.

With additions like the composer John Cage’s original score for Sounds of Venice, and Yoko Ono’s Instructions for Paintings, there’s reason for optimism and impatience. And if Christophe Cherix, the Robert Lehman Chief Curator of Drawings and Prints, is any guide, that optimism is far from unfounded: “This collection raises fascinating questions for audiences and scholars alike,” he says, “regarding issues such as the primacy of idea over process in art making, the legacy of ultimately unrealized or inherently ephemeral artworks, and the role of drawing today as paper becomes an increasingly uncommon repository for artists’ thoughts.”

The acquisition announcement was another indication that the drawing is enjoying a moment, with an expanding spate of dedicated spaces in museums and art fairs. There are of course the old stand by’s like New York’s Drawing Center, founded by the curator Martha Beck in 1977. It has operated continuously since then, hosting more than 300 exhibitions, producing 150 catalogs, and “explor[ing] the medium of drawing as primary, dynamic, and relevant to contemporary culture, the future of art, and creative thought.” The Drawing Center at the Morgan Library exists “to deepen the understanding and appreciation of the role of drawing in the history of art.” They stage lectures, symposia, exhibitions, and master classes, as well as offering research fellowships in the name of fully utilizing the Center’s holdings. So, whether or not this is a golden age for the drawing, there’s surely great enthusiasm for the medium among collectors, curators, and artists alike.

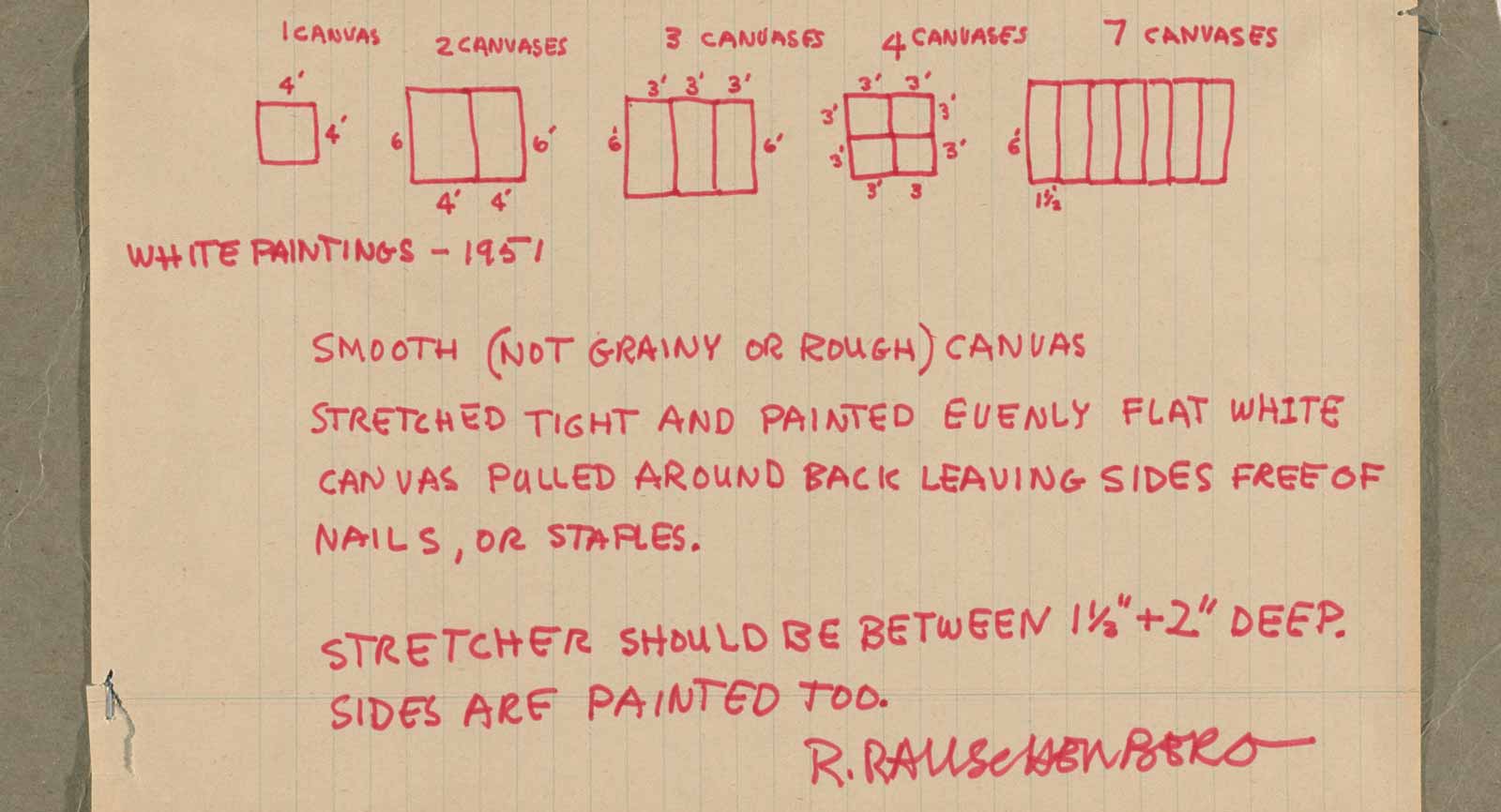

The new MoMA holdings are also squarely in line with the drawing’s versatility. In their foreword to Collecting Prints and Drawings, a volume exploring early modern collecting practices, the scholars Andrea M. Galdy and Sylvia Heudecker, write that “drawings possess an immediate and vigorous quality that makes them particularly suitable as documentary evidence.” Certainly, on an art historical level, a record of Robert Rauschenberg’s vision for his White series offers singular insights. Yet the drawing can seem like the art market’s middle child. It might lack the grandeur of a painting or original sculpture. It’s less easily accessible to collectors than a print, where even a relatively limited edition might run to a thousand and carry a modest price. And there’s at times a suggestion of the workmanlike about the drawing. Something preliminary, a staging ground ahead of the ascent. Nonetheless, consider a finely rendered architectural drawing completed ahead of construction, or a study undertaken before a painting. There are offerings in each of those veins so finely rendered as to deserve a place of honor in collections. To limit what qualifies as a masterful drawing is to remain blind to much of the medium’s appeal.