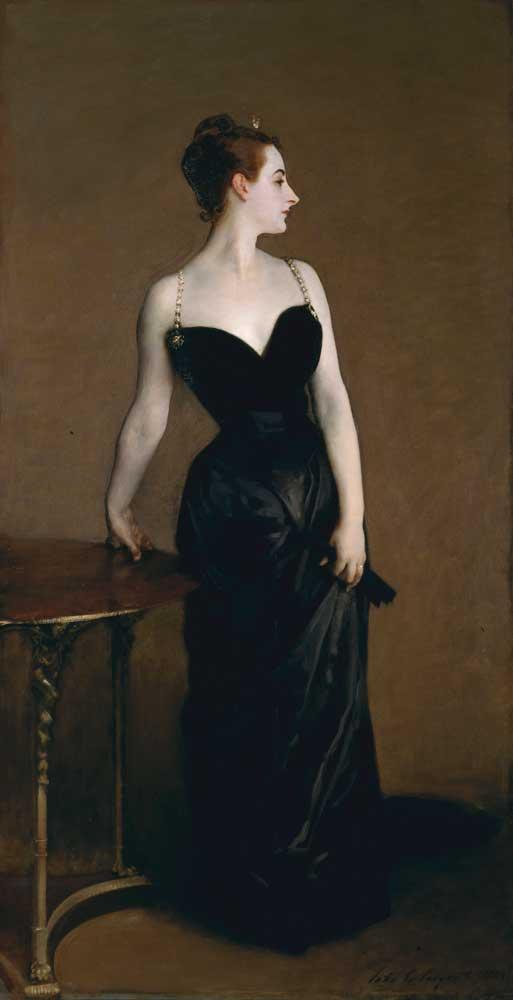

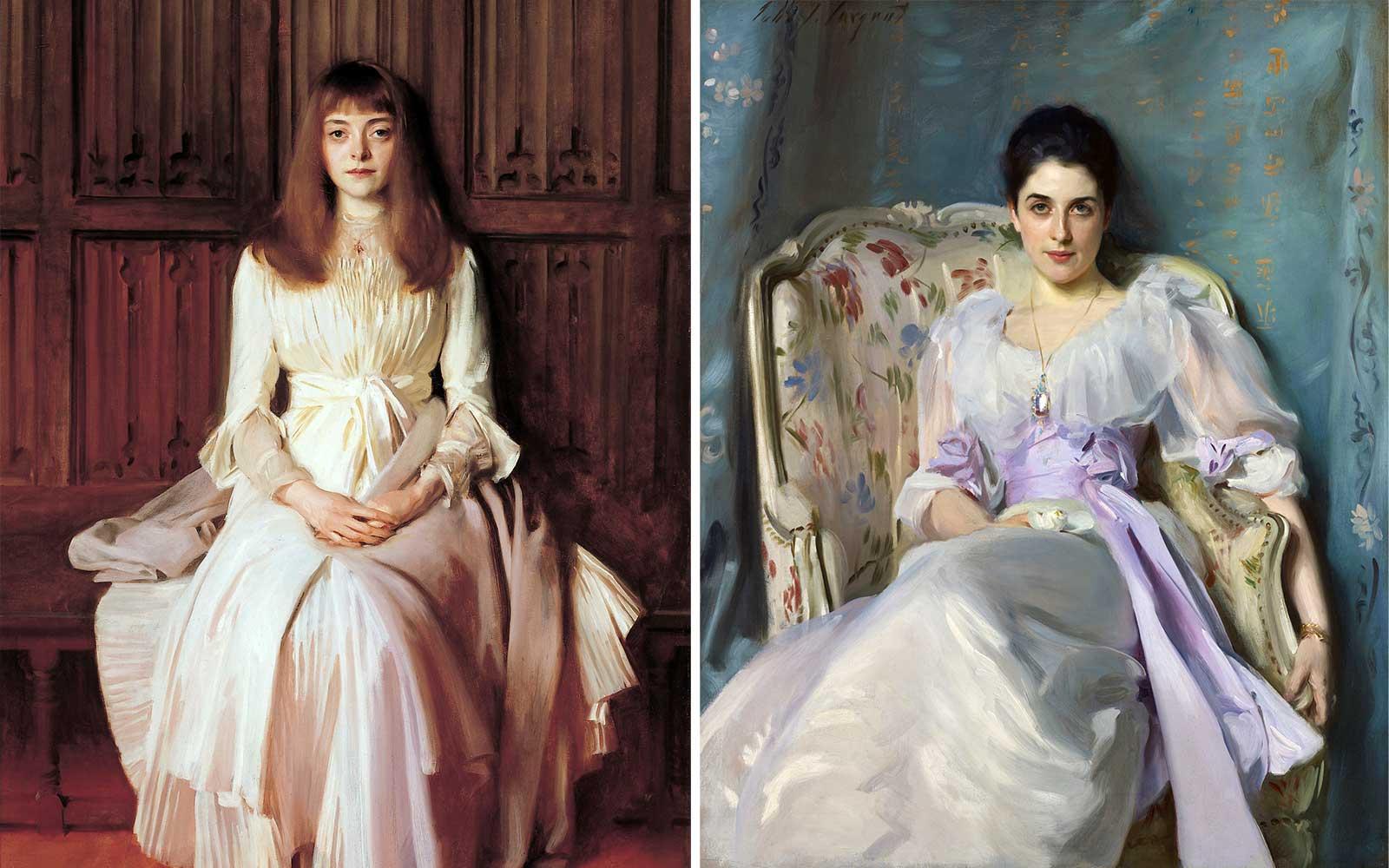

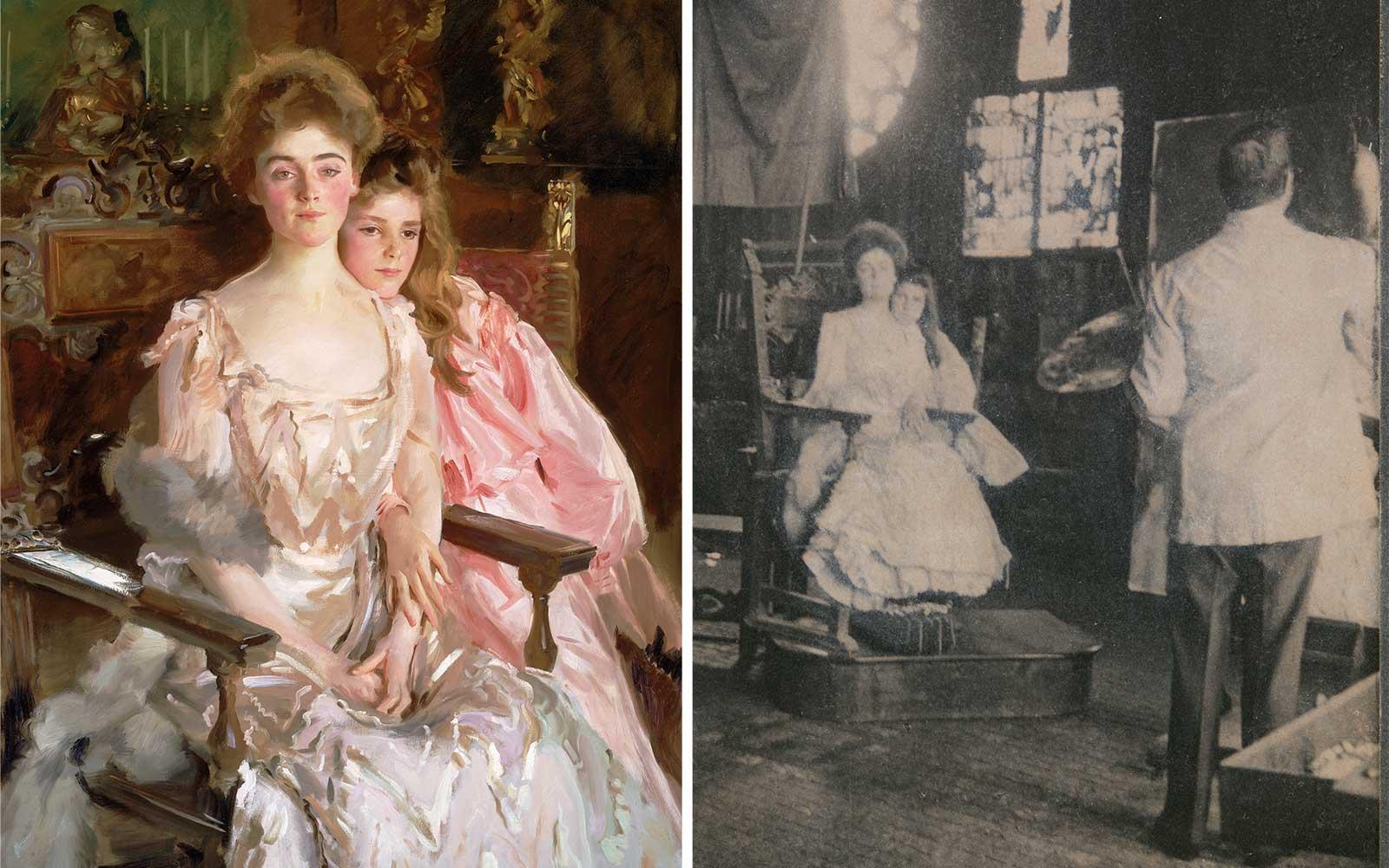

It is the inherent theatricality in Sargent’s approach to dressing and posing his subjects that infuses the exhibition with a heightened sense of drama and adds to the pure pleasure that viewing these masterworks of painterly bravura invokes. Sargent was the most successful portrait painter of his generation. Known for his exquisite ability to render the elegant soft fuzz of velvet or the sheen of satin in the luxuriant folds of a well-dressed Edwardian lady’s gown, Sargent used fashion not only to demonstrate his painterly skill but as a powerful tool to depict identity and personality. He regularly chose the outfits of his subjects or manipulated their clothing. This innovative use of costume was central to his artwork.

MFA Boston had begun to conceptualize this exhibition in 2016 long before COVID struck. “Our interpretive strategy was affected by audience input,” Hirshler elaborates. “In 2018, we invited museum goers’ participation via our Exhibition Lab: Sargent and Fashion. We gave people the opportunity to look behind the scenes to see how exhibitions are created…. We asked the public what type of manikin they preferred. [to display the garments]…. In offering five different approaches to labeling we discovered the audience was eager for more story, so the labels are longer. They wanted to know three things: 1. The identity of the sitter, 2. The significance of the clothing, and 3. The relationship of the sitter to the artist. More than just giving facts, my goal was to inspire people to look.”

Critics of Sargent have long accused him of being the servant to his mostly wealthy patrons. Hirshler, who is known as a Sargent scholar, was surprised to learn this was not the case. “I became aware how in control he was. His sitters repeatedly said that ‘Sargent told me what to wear,’” she said. In some cases, he used his imagination. MFA Boston conservator Lydia Vaghts described his preparation for the Portrait of Lady Helen Vincent (1904): “This is really an invented garment," said Vaghts. "It was originally white, and Sargent completely repainted it.” Known as a great English beauty, Lady Vincent wore a flowing white dress to pose on the balcony of her apartment in Venice. Sargent painted her wearing that white dress but was dissatisfied, and scraping off the white paint, he proceeded to paint her in black which contrasted with her swan-like neck and pearly white skin. He then wrapped her in a pink satin swath of fabric that may never have existed. While many of the works come from the MFA’s own extensive collection of Sargent, this painting is on a rare loan from the Birmingham Museum of Art.