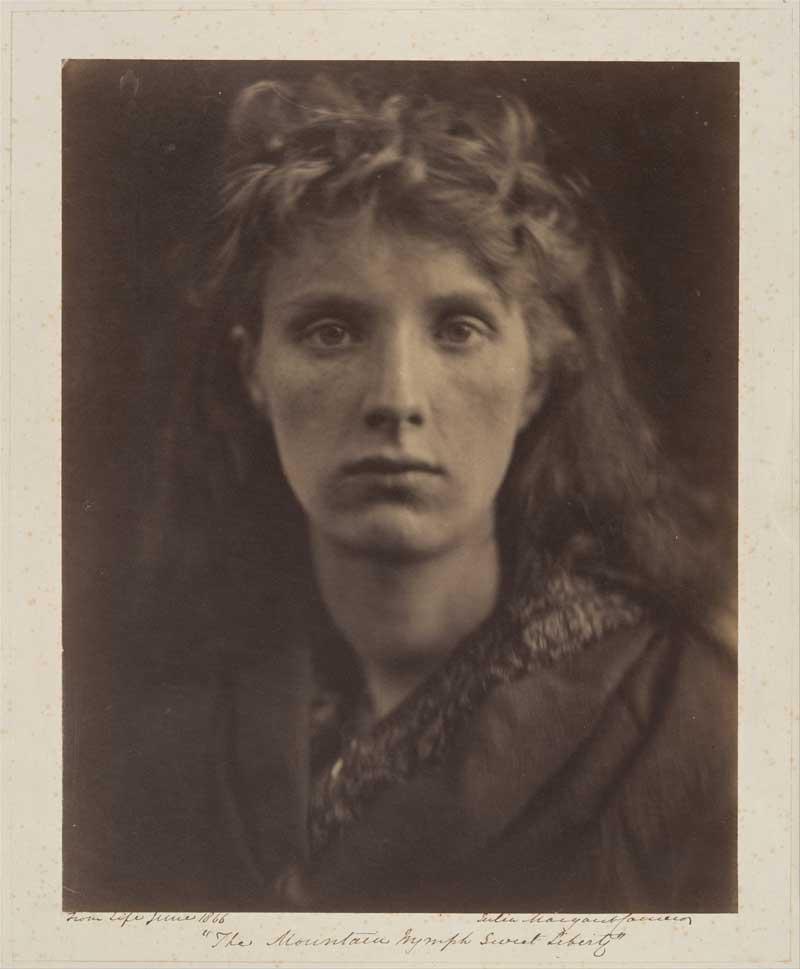

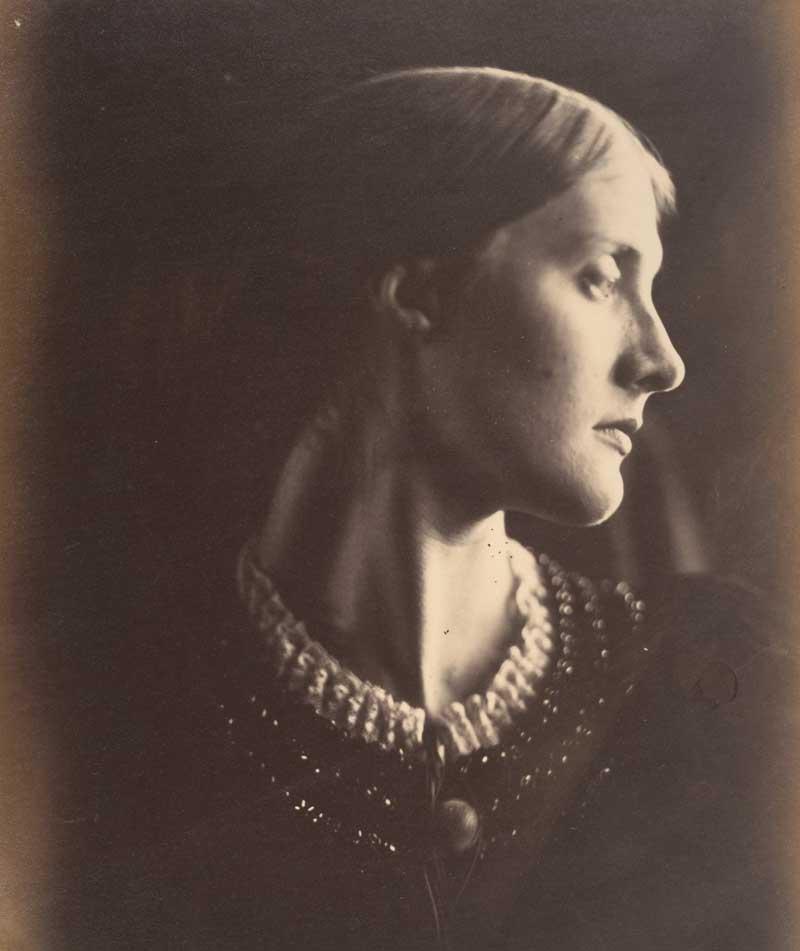

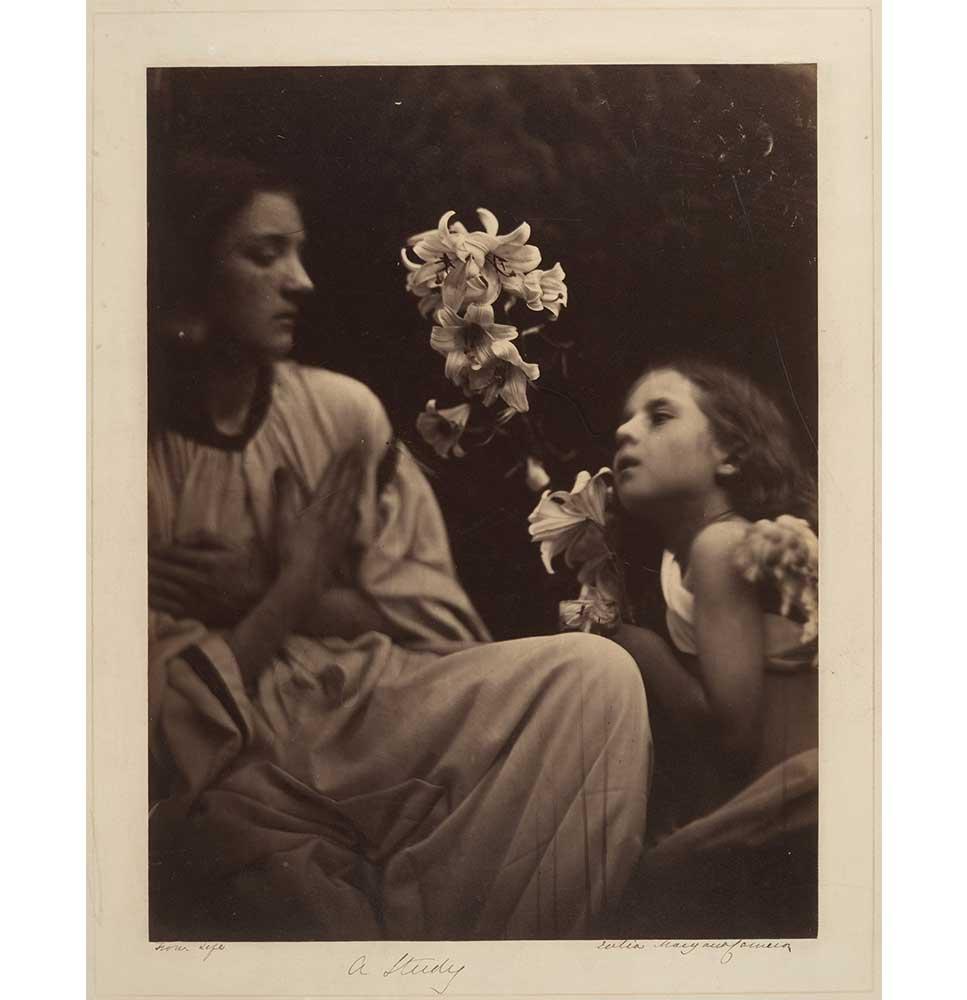

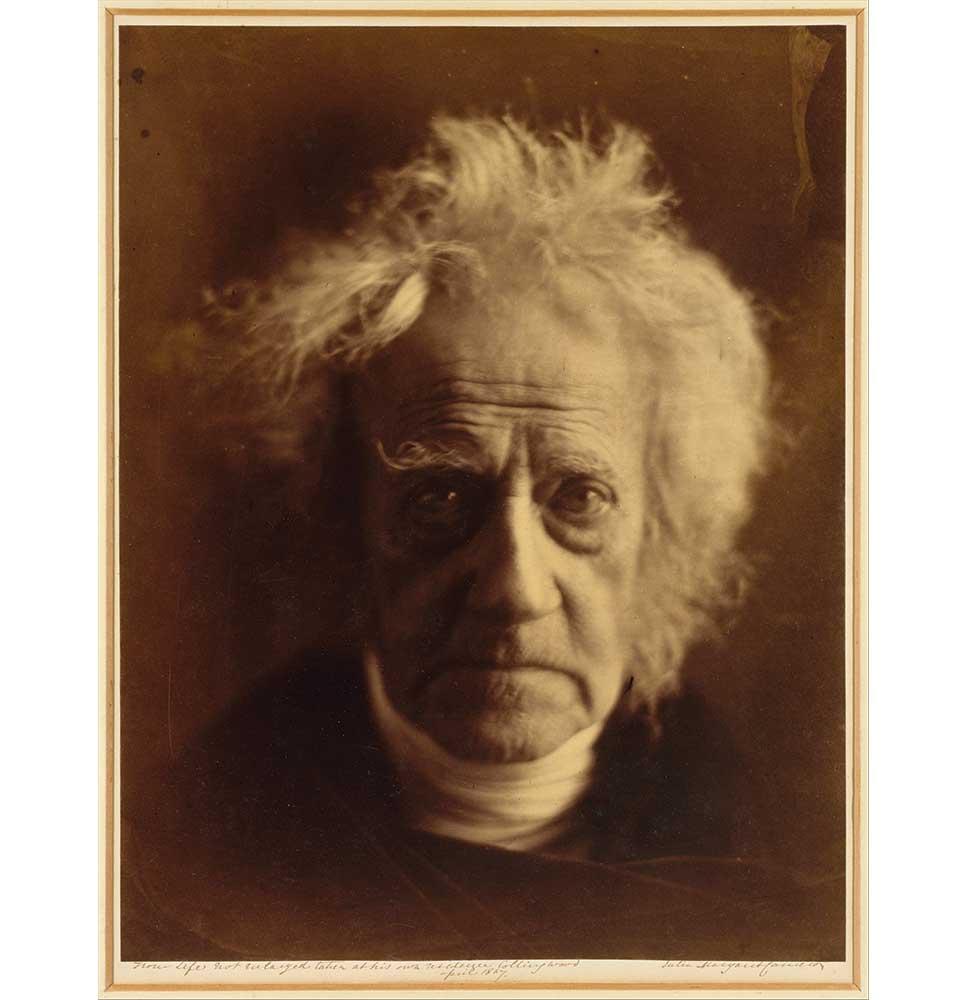

Julia Margaret Cameron’s early critics were concerned with beauty—the beauty of her sitters, her sensitivity in capturing it, her own physical charm, and, of course, where she failed to meet certain aesthetic ideals. When, in 1926, Bloomsbury Group-celebrities Virginia Woolf and Roger Fry wrote the first earnest appraisal of Julia Margaret Cameron’s photography, Fry remarked, “Beauty was a serious matter to Mrs. Cameron and her beautiful sitters.” Woolf too defined Cameron by this trait, partially in contrast to her Victorian setting: “it was from her mother, presumably, that she inherited her love of beauty and her distaste for the cold and formal conventions of English society.” Woolf even claimed that, at the end of Cameron’s life, she lay observing a starry sky, when she “breathed the one word, ‘Beautiful,’ and so died.”

Woolf and Fry’s short volume is called Victorian Photographs of Famous Men and Fair Women. Like the above statements, the title could be read and accepted as an of-its-time neutral or positive judgment of Cameron’s work. Yet Woolf, astute as she was, may have been probing at the gendered dialogue that surrounded Cameron and her work by playing with the notion of “fair women” and beauty itself.