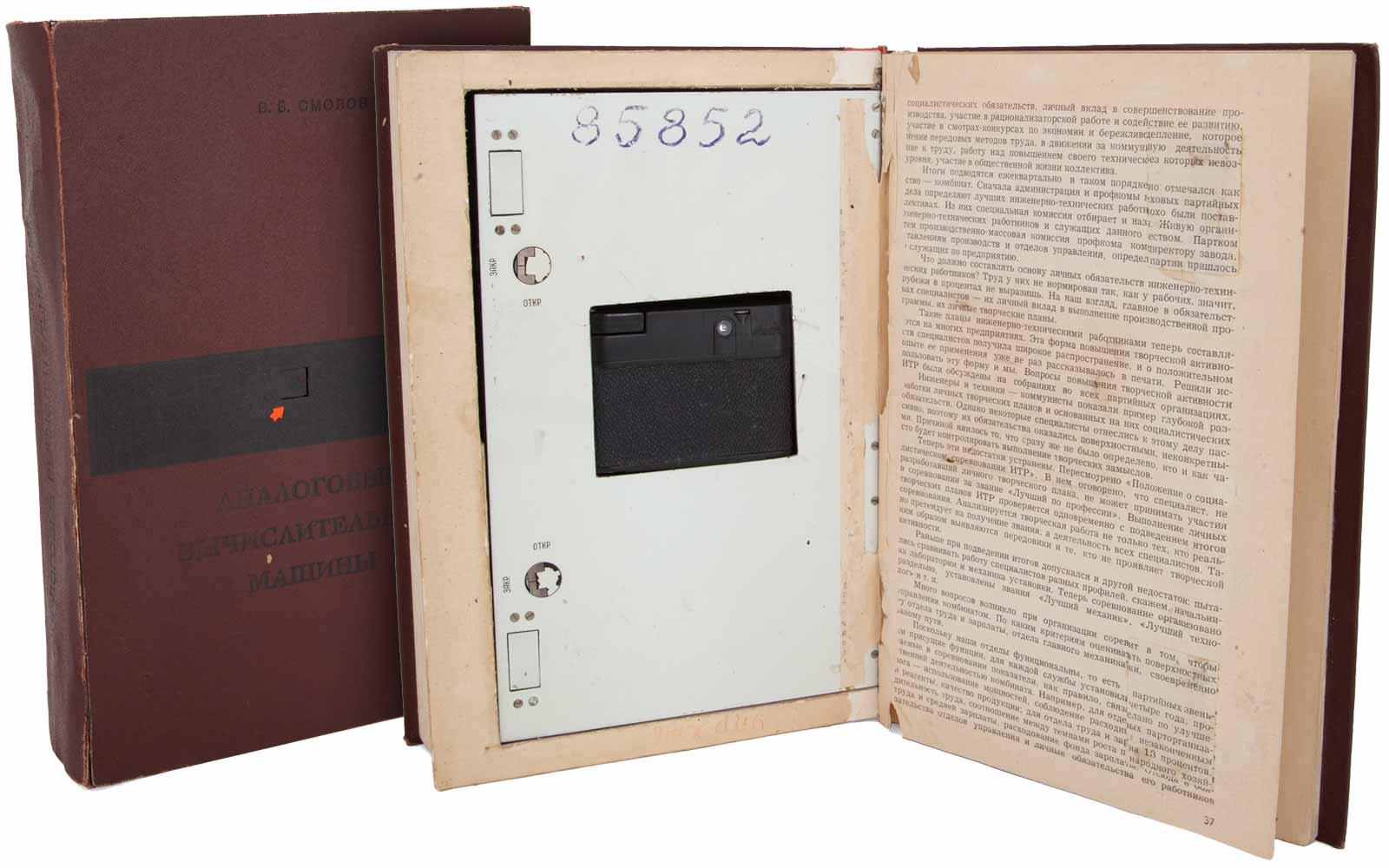

In the age of smartphones and smartglasses, we might feel blasé about a camera hidden in a hollowed-out hardcover book or a carton of Marlboros. As clunky as they may seem now, these objects were novelties used by covert intelligence operatives in the middle of the twentieth century. More impressive might be a ring camera, similar to the one that appears in the 1985 James Bond flick, A View to a Kill.

All three items can be found within a vast collection of spy relics that does actually read like a list of Bond gadgets, including all manner of code machines and surreptitious recording devices, which, until recently, formed the nucleus of New York City’s KGB Espionage Museum. The gold-plated ring camera, measuring 1 3/8” by 1½” and containing only enough film for one discrete snapshot, is particularly rare.

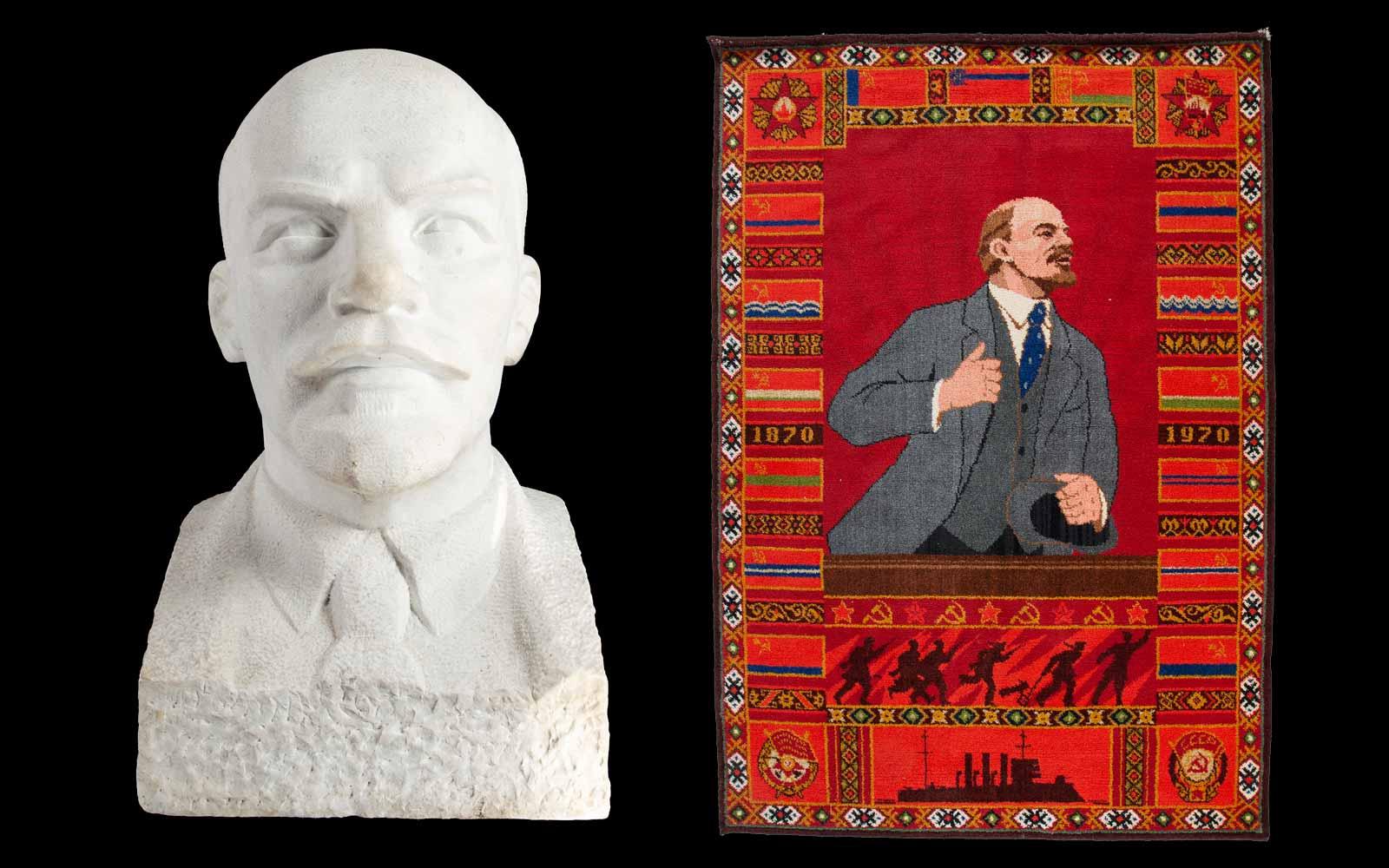

The museum’s co-curators, Julius Urbaitis, and his daughter, Agne Urbaityte, stocked the public space with Urbaitis’ personal collection. Urbaitis, 57, grew up in the shadow of a Russian military unit in Lithuania and began collecting military badges as a child. He also collected more mundane objects, such as match labels, vinyl records, stones, and passkeys, but he was drawn to the World War II and Cold War periods. He refined his collection until it was almost exclusively devoted to the Soviet secret police force known as the Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti (KGB). “I was fascinated by the search process and KGB artifacts are hard, complicated to find,” Urbaitis writes via email from his home in Kaunas, Lithuania.