In his diaristic book on Willem de Kooning, Reflections in the Studio, Edvard Lieber wrote:

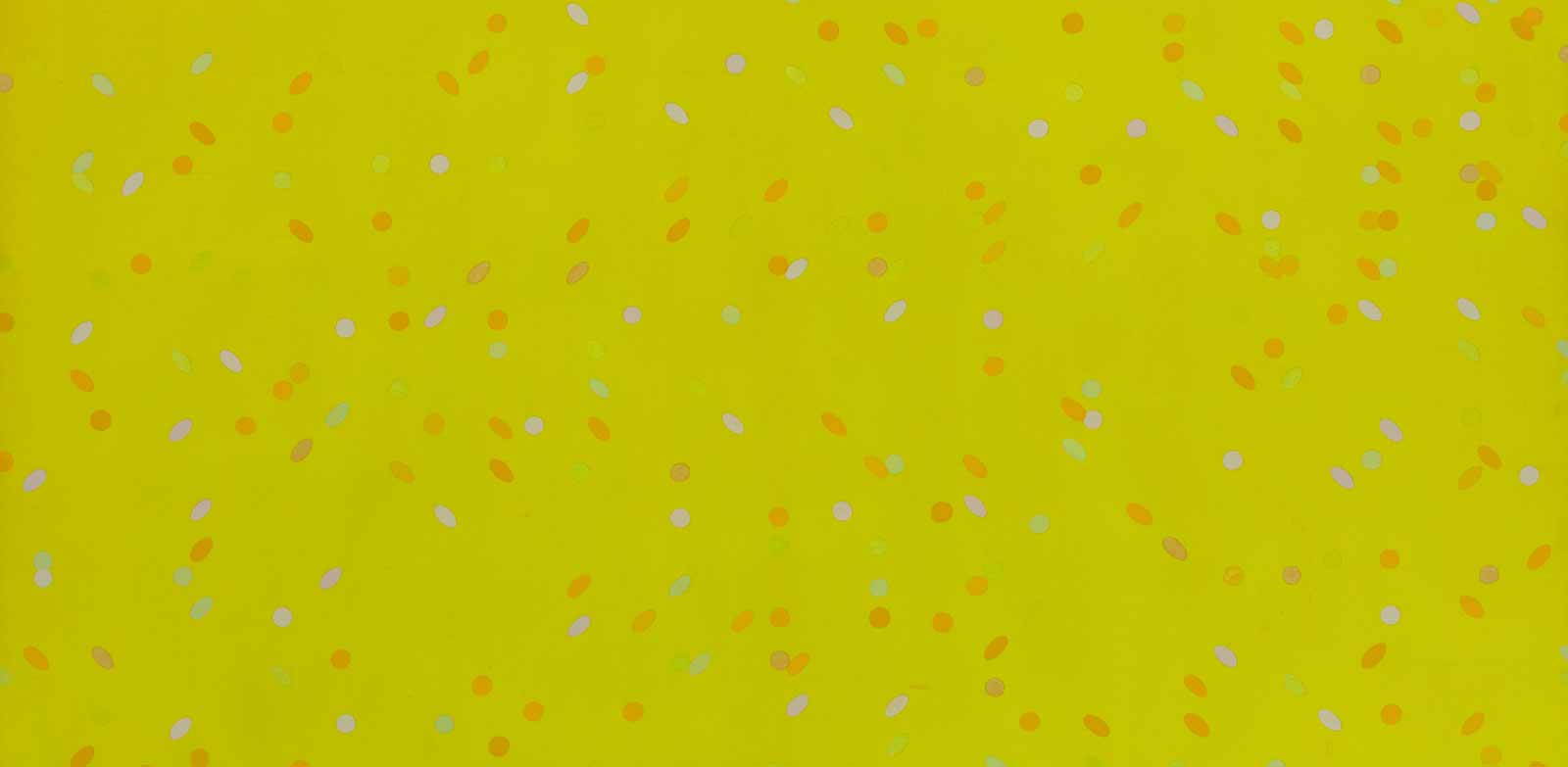

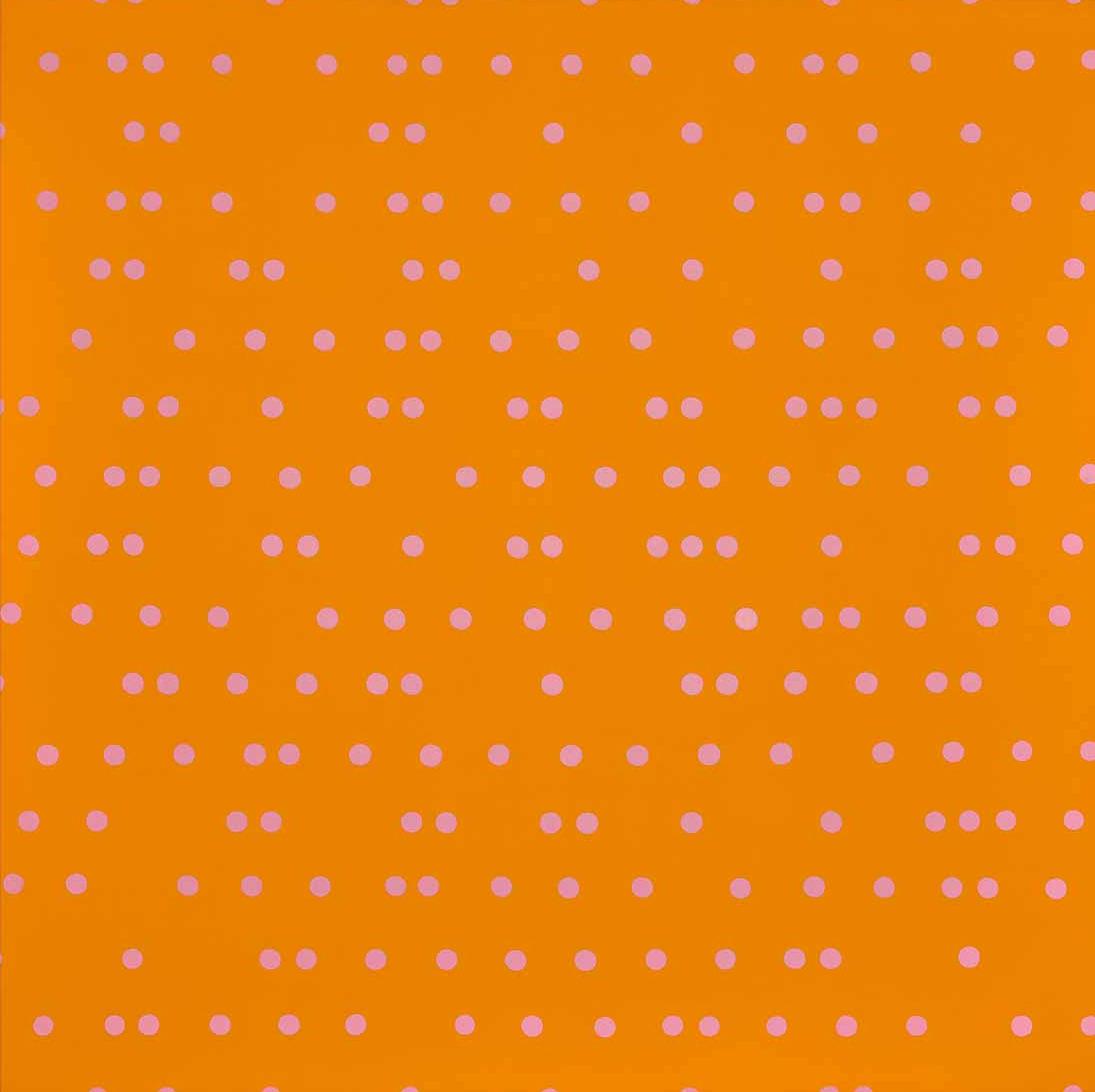

“In the late 1980s hyperactive forms began to appear in his paintings. ‘I’m back to a full palette with off-toned colors,’ de Kooning remarked. ‘Before it was about knowing what I didn’t know. Now it’s about not knowing that I know.’”

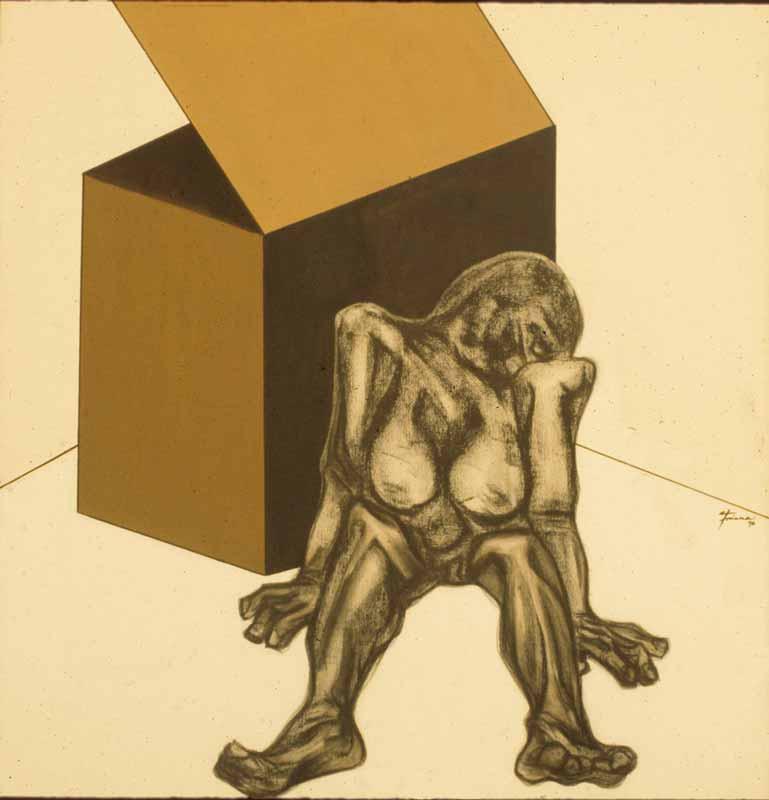

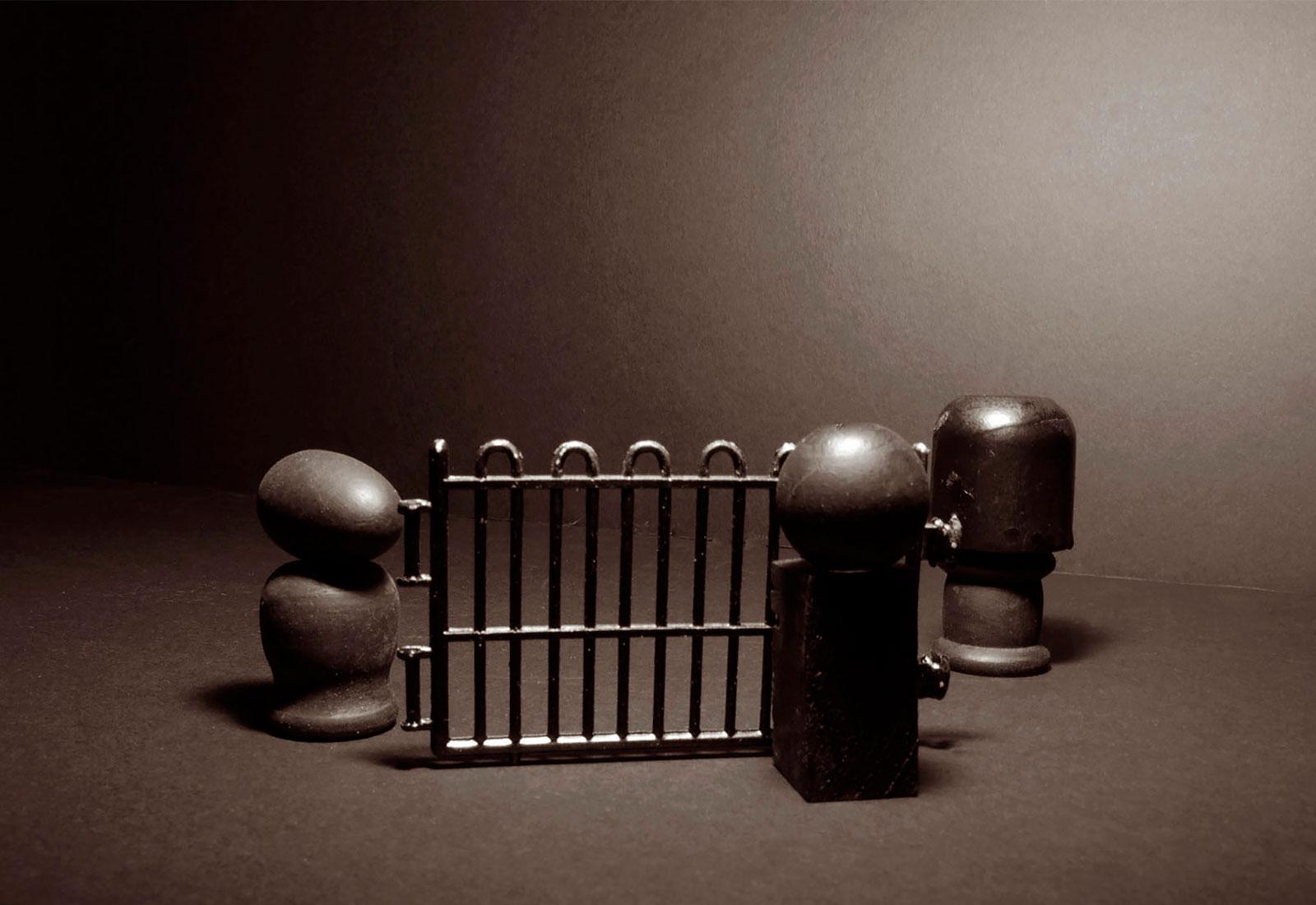

There is much to ponder about creative shifts in late-career artmaking. It’s a subject that has always fascinated scholars and audiences in all the arts because we usually expect painters, like musicians and poets, to grow more mellow or lyrical with advanced age.

Think of de Kooning’s angry women or architectural landscapes yielding to his famously thinned-out gestural paintings in soft pinks and greens and blues. De Kooning was in the throes of dementia, and we wonder what was intentional and what was instinctive—even unconscious—in his production. And then, of course, we wonder if this even matters or should be allowed to influence how an audience perceives the work.