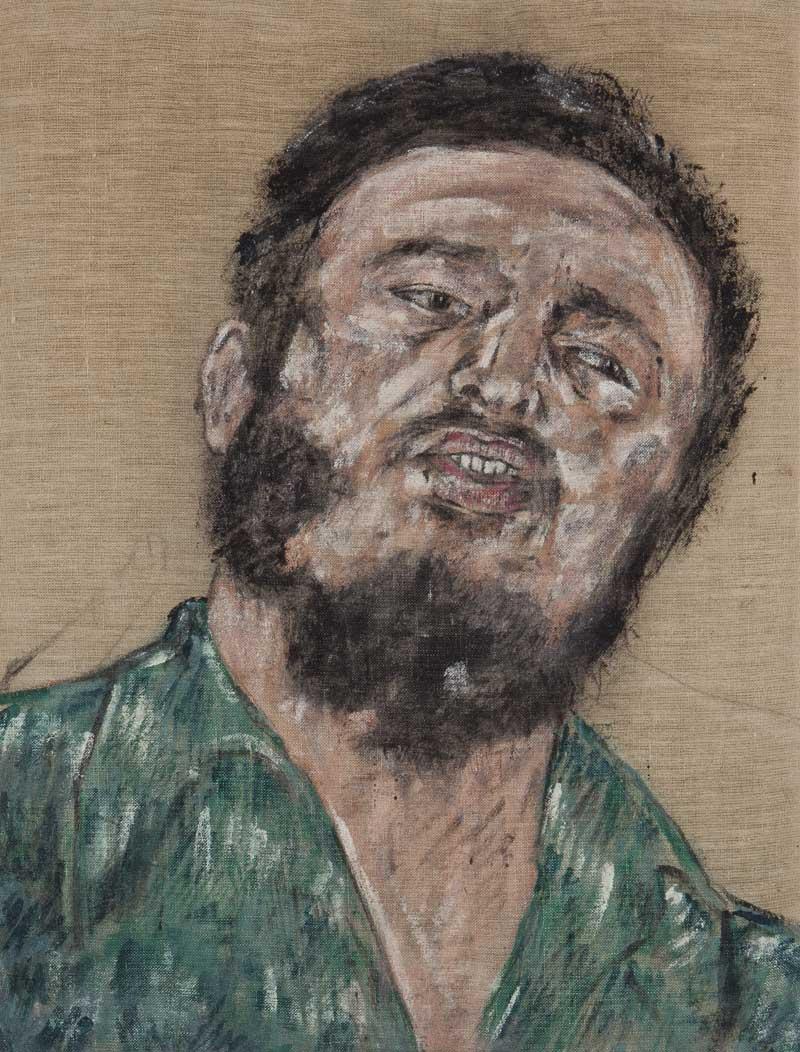

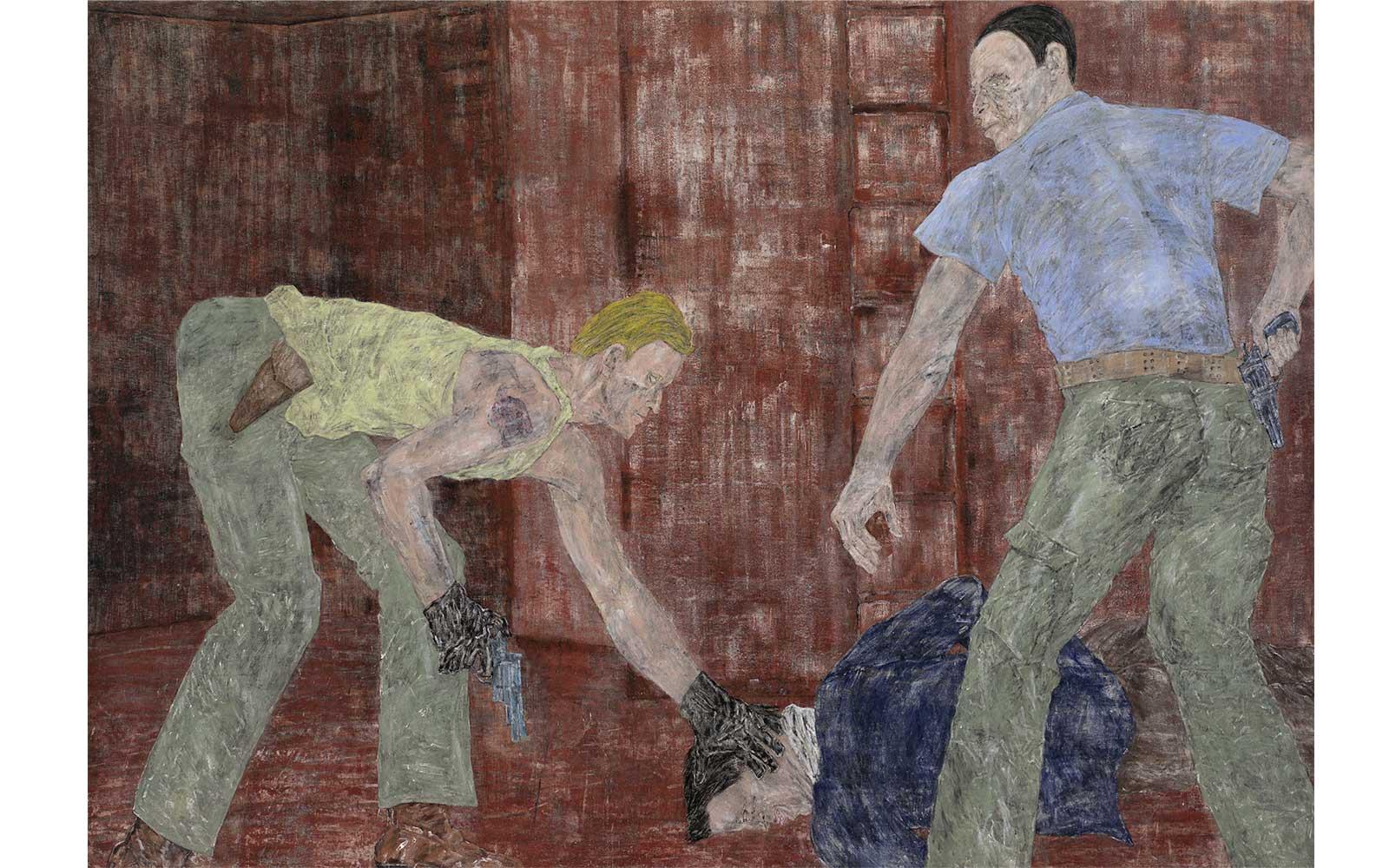

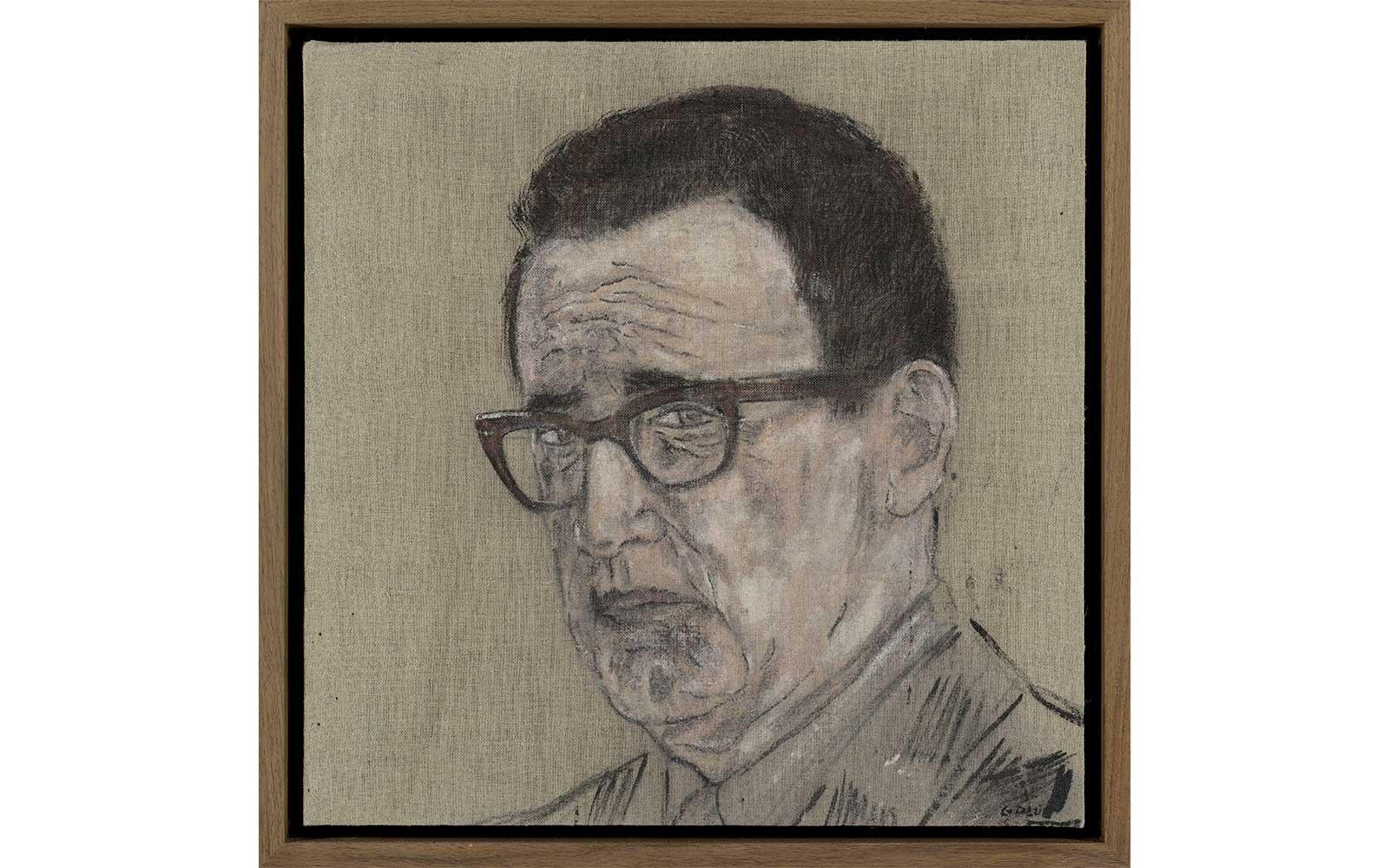

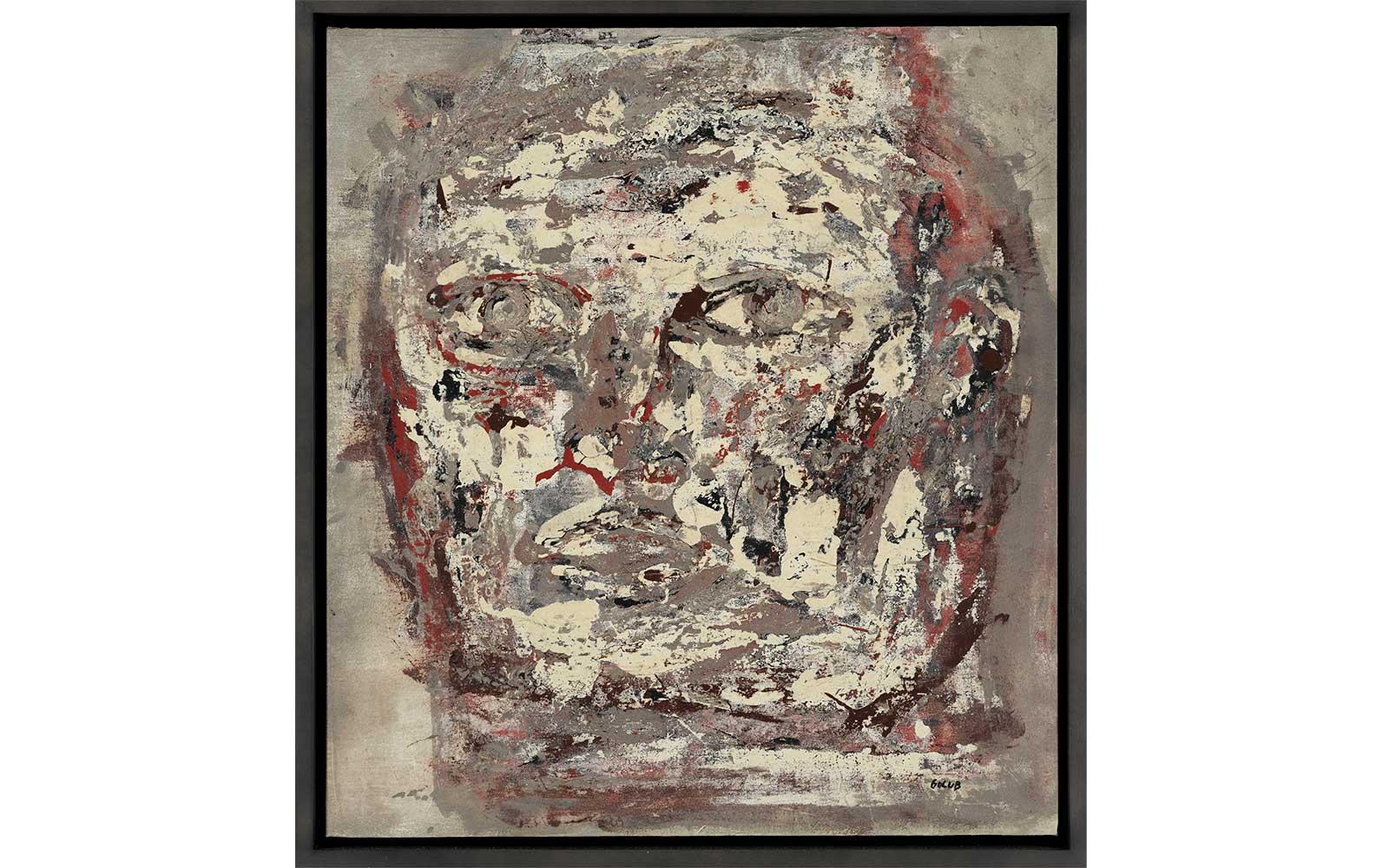

The visceral paintings of American figurative artist Leon Golub (1922-2004) confront us. The viewer serves as a witness. We are compelled to look. There is an initial shock value. Then comes the long, slow, seeping guilt that coincides with consciousness, a recognition that we are complicit, either directly or indirectly, in these atrocities. Golub’s paintings exude an undeniable psychological presence that transcends the moment in time when they were made.

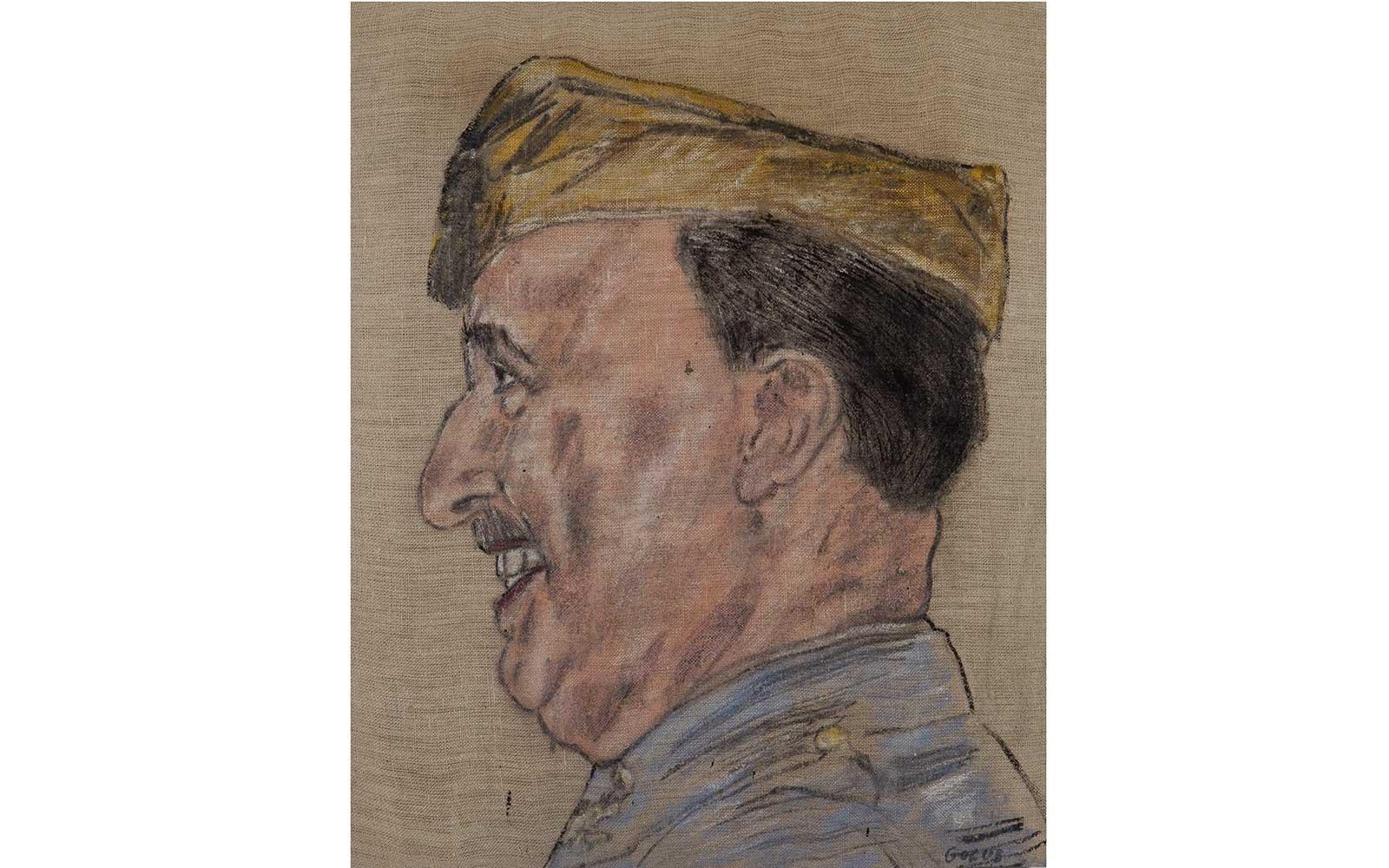

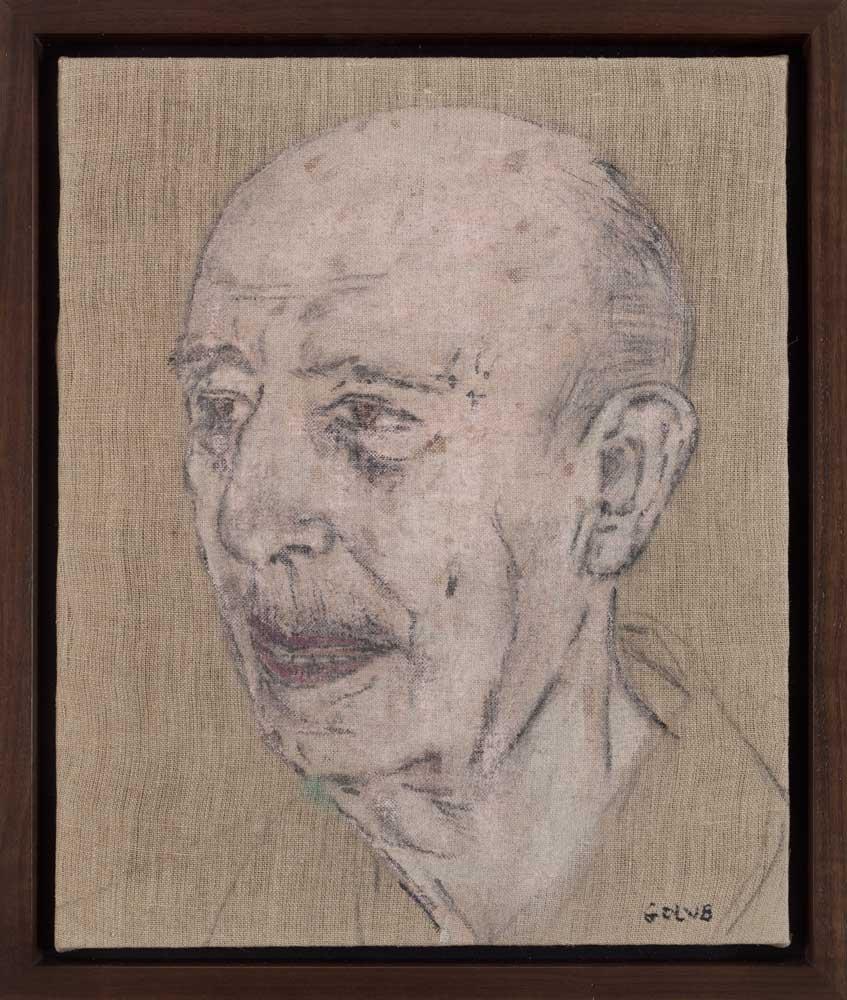

Leon Golub was born on January 23rd, 1922, in Chicago, Illinois where he attended the University of Chicago. He served in WWII and saw the barbarity of the Nazi concentration camps. When he returned from the war, he met his future wife, artist Nancy Spero (1926-2009), when they were both students at the Art Institute of Chicago, where he graduated in 1950 with an MFA. Spero became his collaborator in art and life and was a respected artist, feminist, and political activist building her own impressive career while bearing and raising their three sons.

Drawing solely from the works in their own collections, The Hall Art Foundation – founded in 2007 by collectors and philanthropists Andrew and Christine Hall, along with the Ulrich Meyer and Harriet Horwitz Meyer Collection – was able to mount this career-spanning exhibition with works from the 1940s until the artist’s death in 2004. Their extensive investment in Golub’s work speaks to the acknowledgment of the universal impact and long-term relevance that these images will continue to have for generations to come.