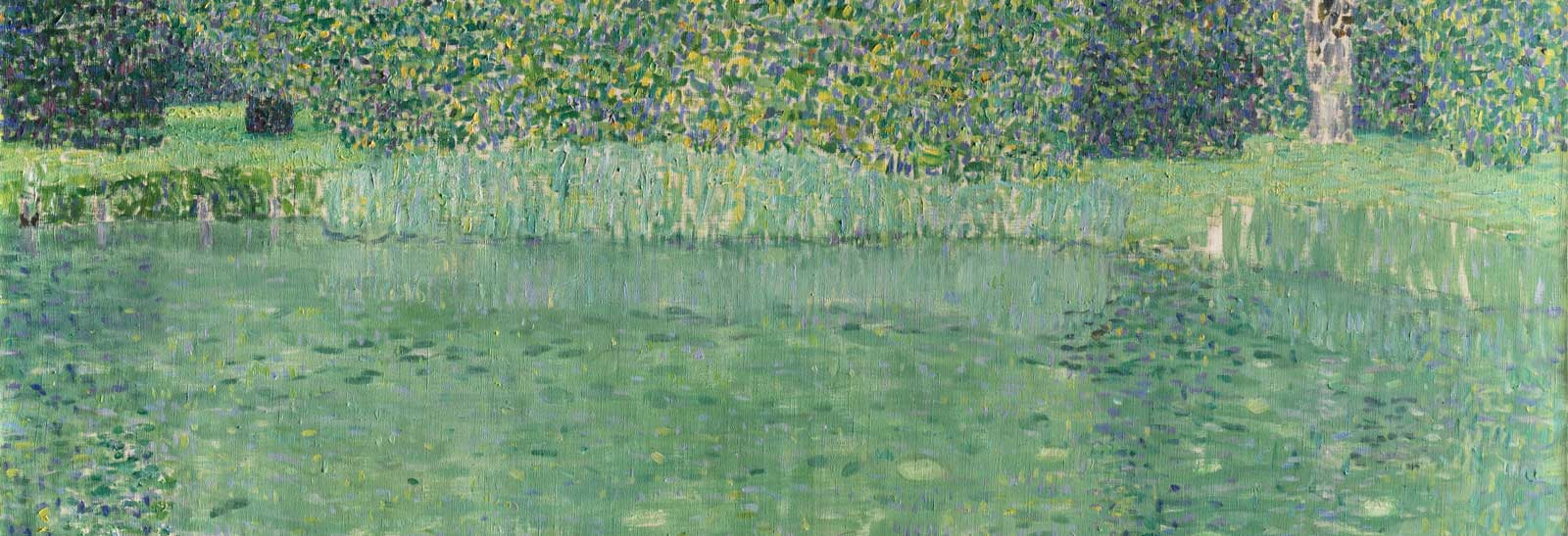

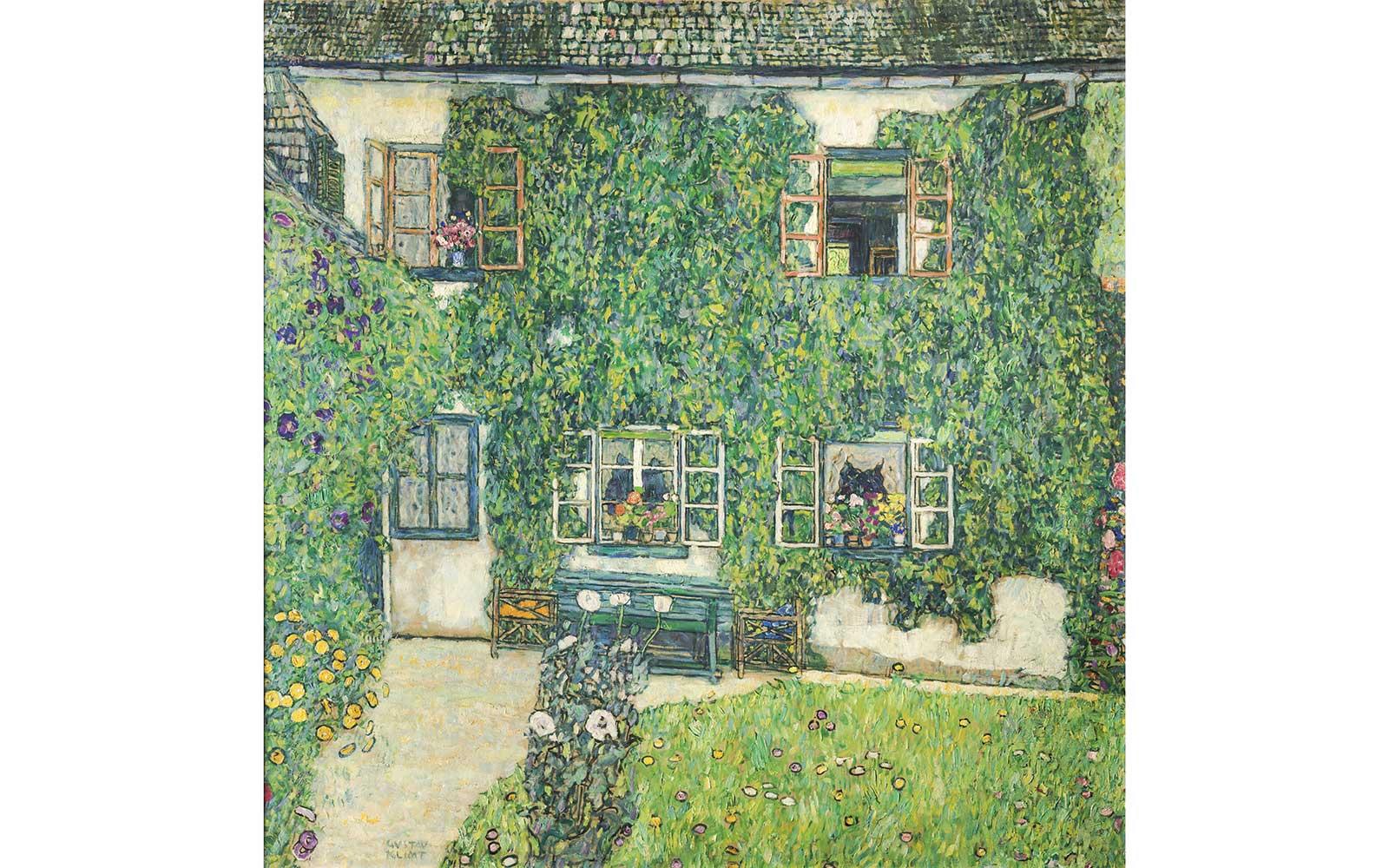

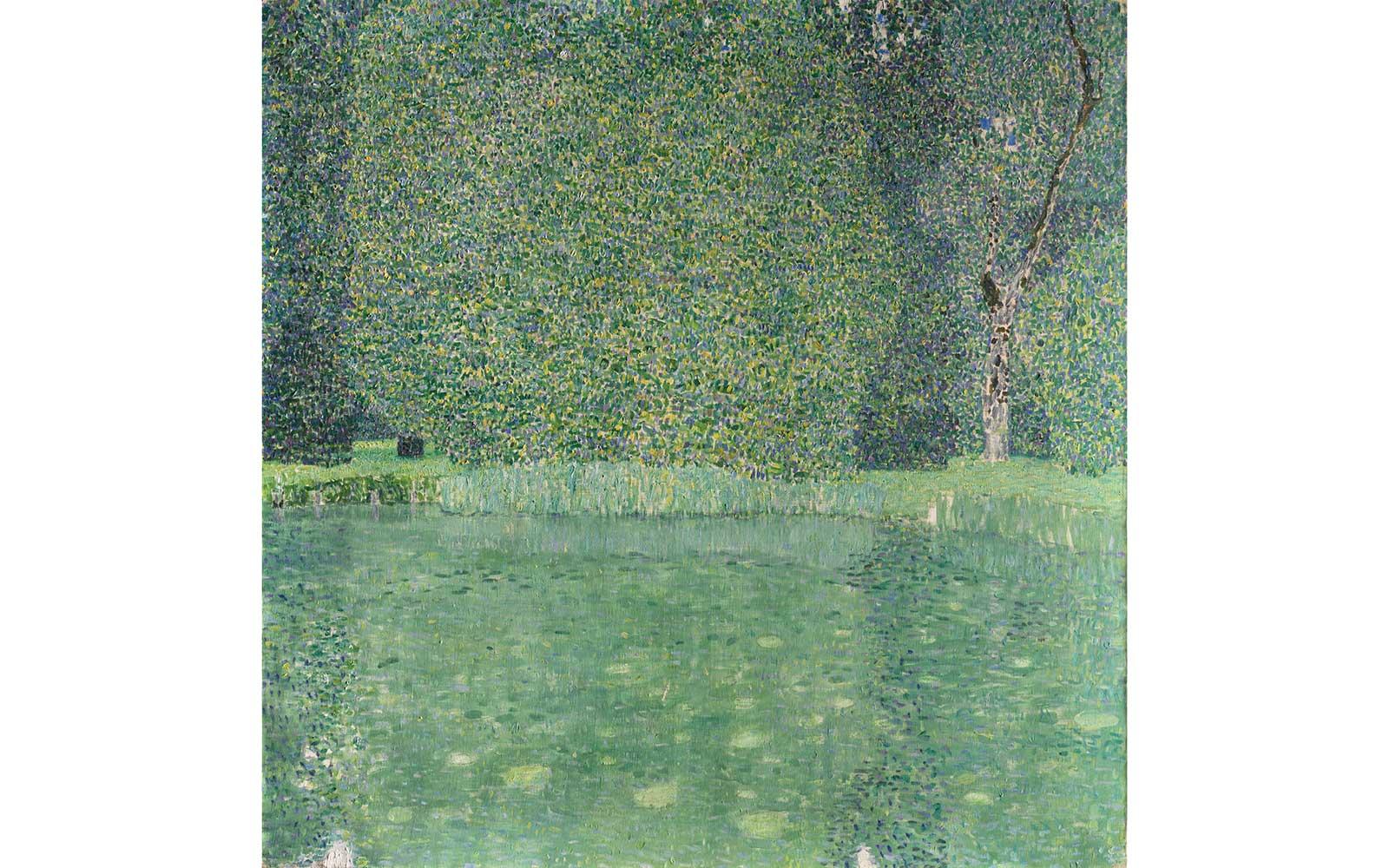

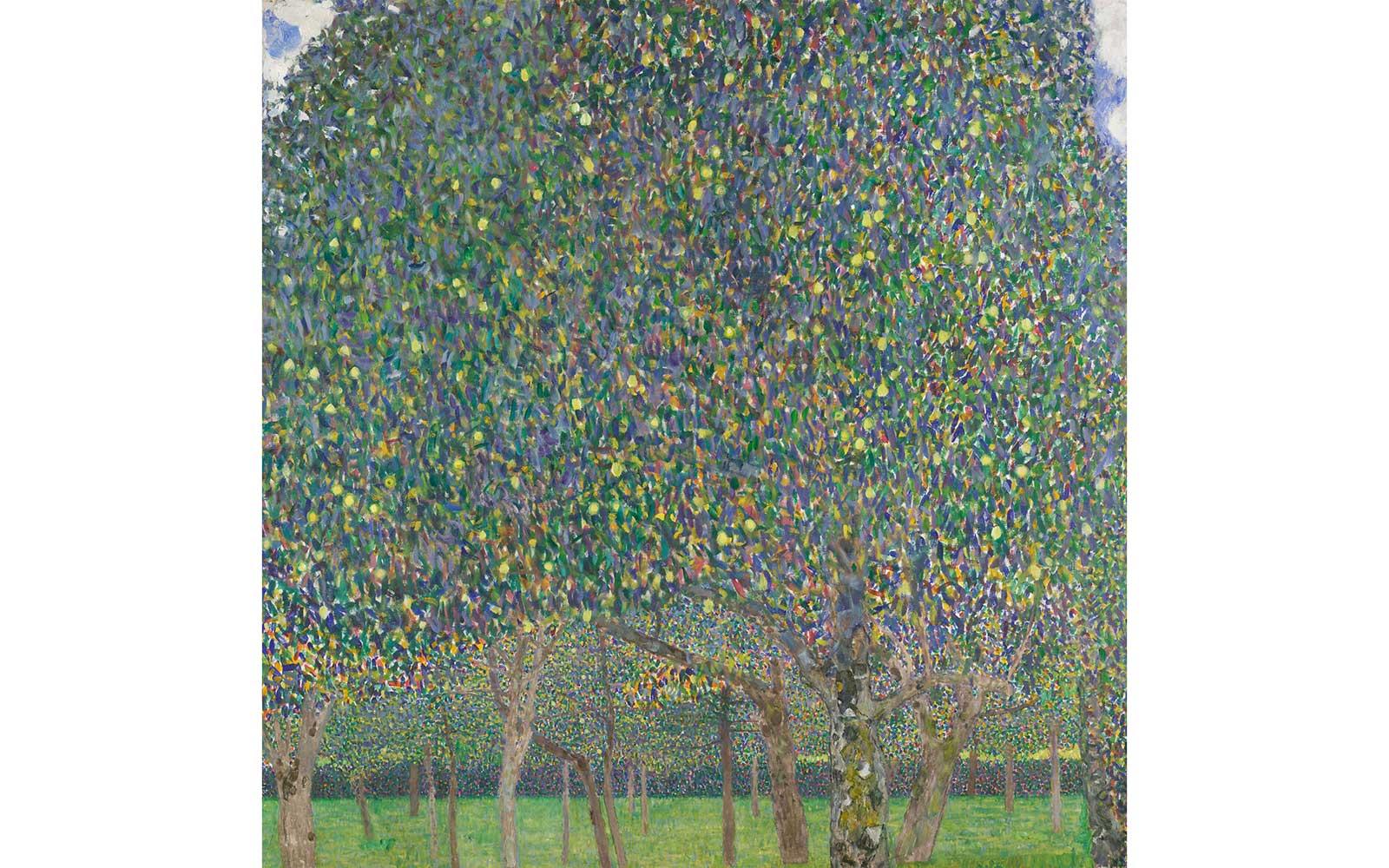

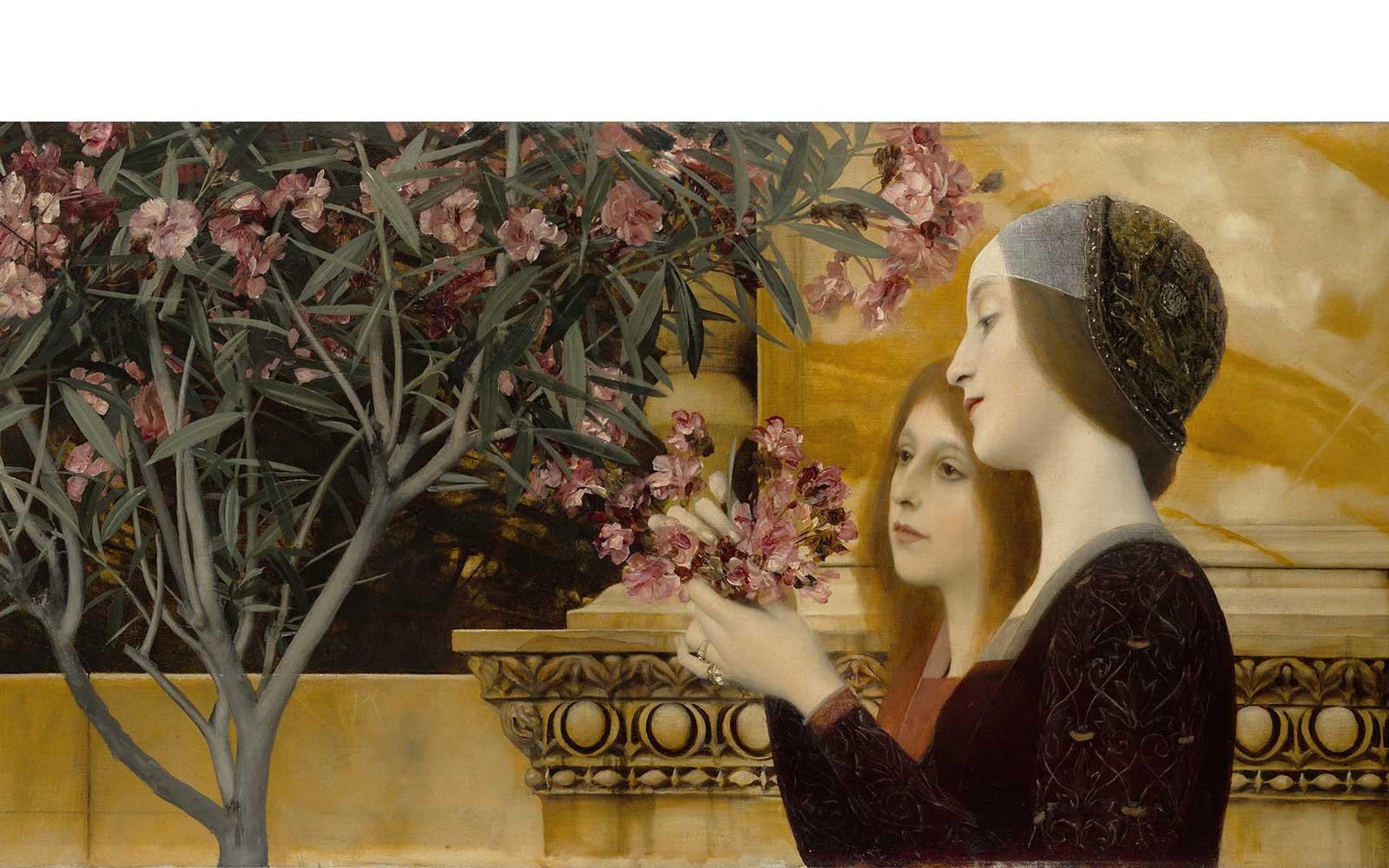

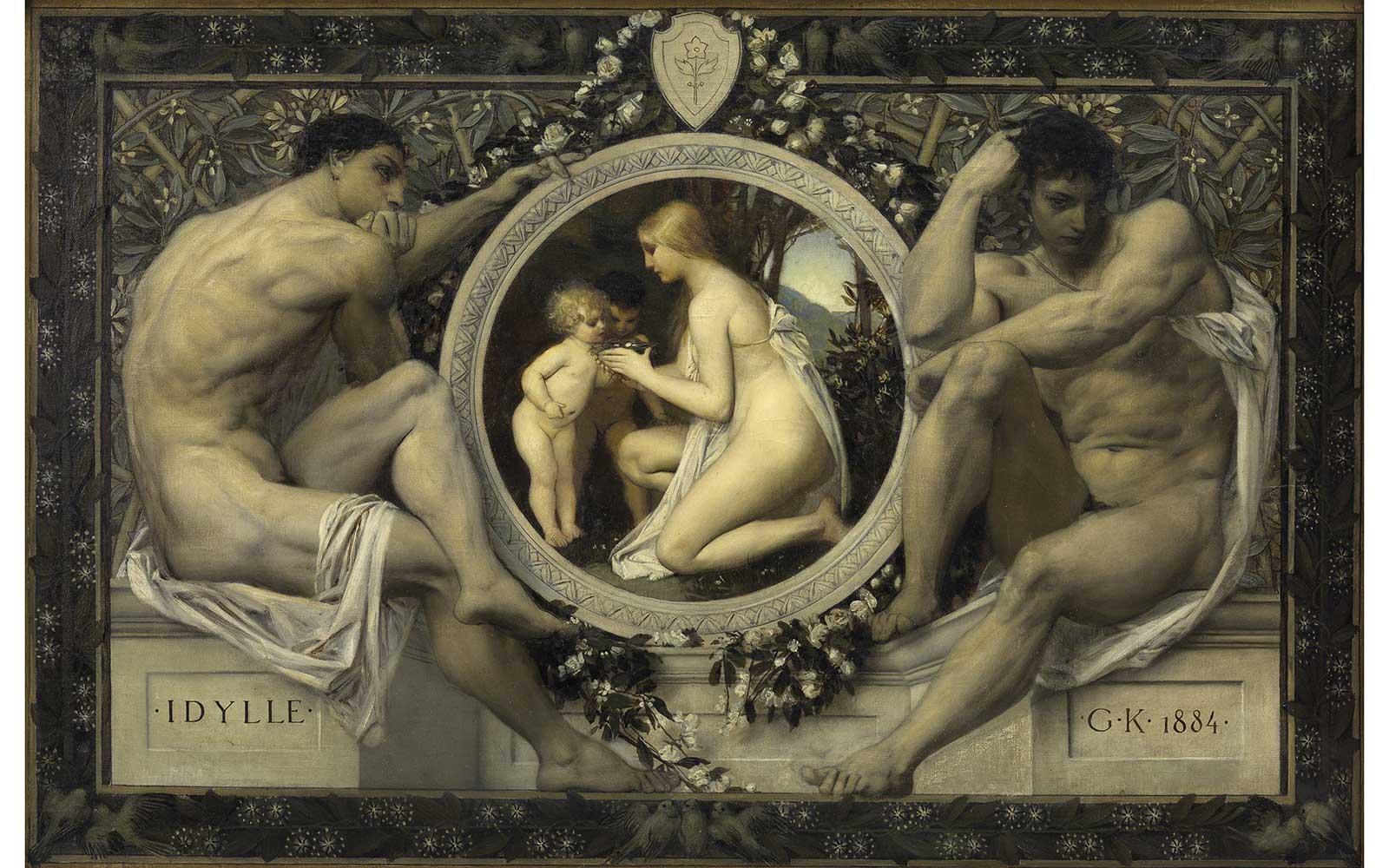

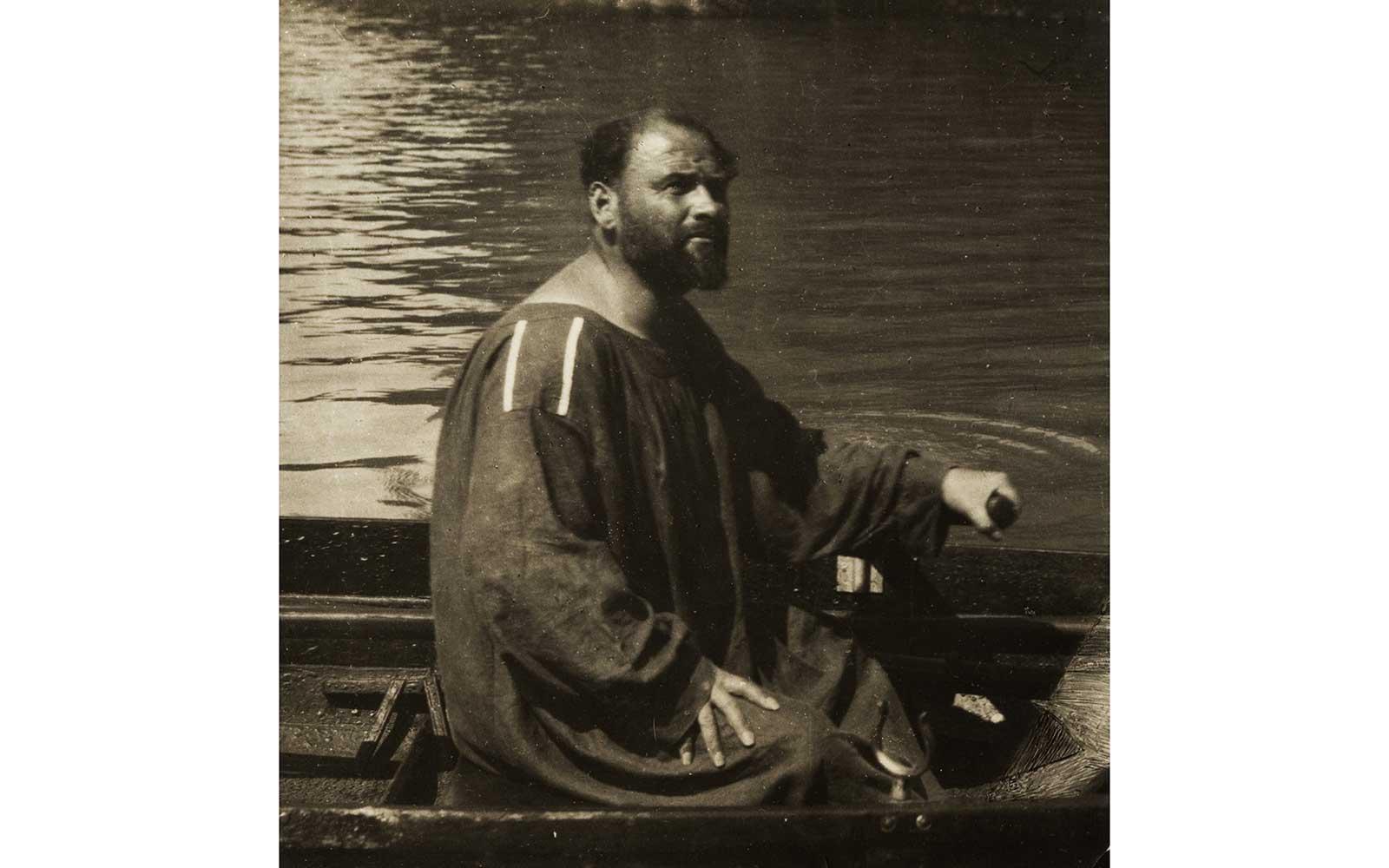

Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) is remembered as one of the foremost Symbolist painters of Austria, renowned for his swirling, gold-leaf portraits of women that epitomize sensuality and mystique. Less known for his landscapes today, Klimt was dedicated to the genre for years, often spending his summer holidays in the countryside painting the rural terrain he inhabited. In looking at these works in "Klimt Landscapes," the latest exhibition at New York’s Neue Galerie, one can see how Klimt’s portraiture practice intertwines with his landscapes, as the same life and emotion evident in his portraits are echoed—and even multiplied—in his pastoral scenes.

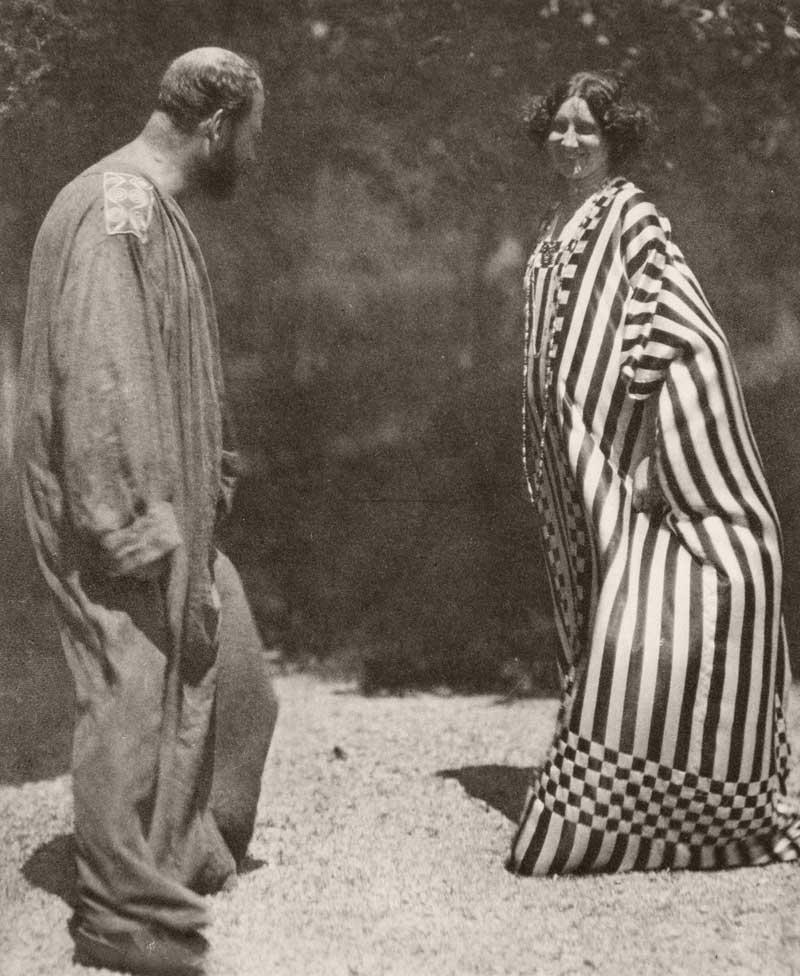

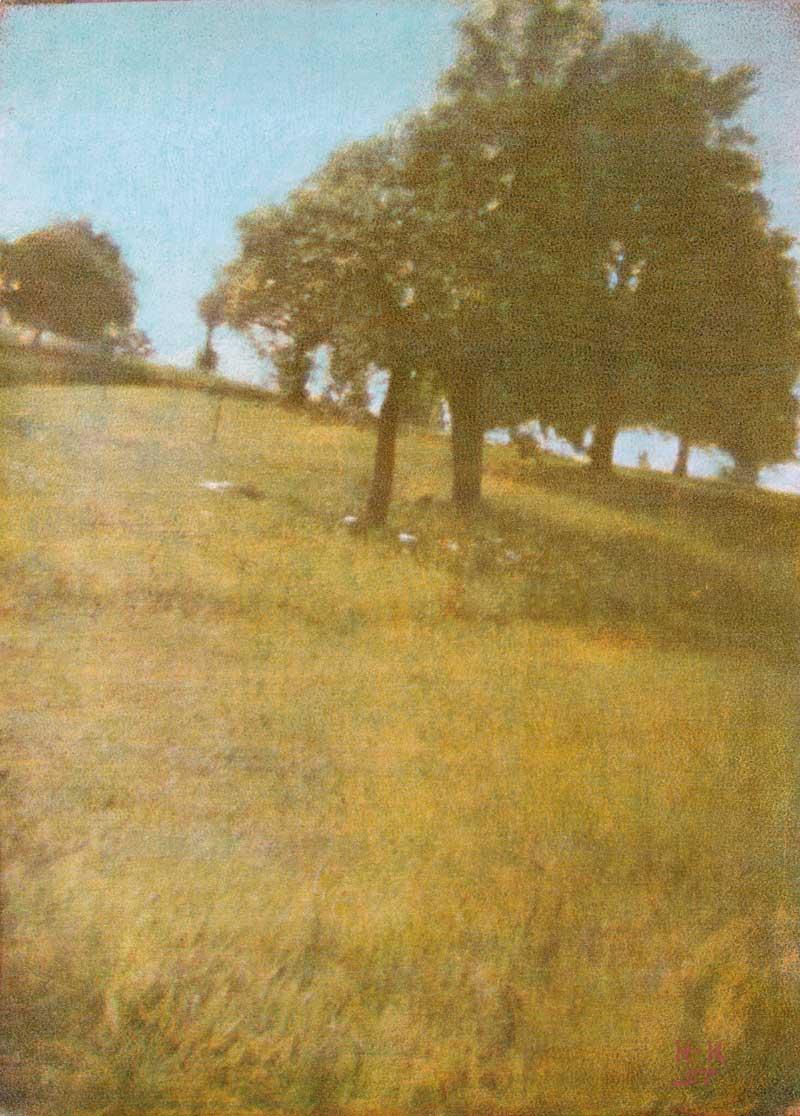

In a 1901 note to his companion and muse, Emilie Flöge, Klimt writes, “It is terrible, awful here in Vienna, everything parched, hot, dreadful, all this work on top of it, the ‘bustle’—I long to be gone like never before.” And off he went to Attersee, one of the largest lakes in the Salzkammergut region near Salzburg, where the artist would spend each summer accompanied by his avant-garde artistic circle.