When a group of European Surrealists immigrated to Mexico in the late 1930s to escape World War II, they found a culture in which their art would flourish. French poet and critic Andre Breton drafted the Manifesto of Surrealism in 1924. After visiting Mexico in 1938, he called it the most surreal country in the world. Salvador Dalí declared, “There is no way I’m going back to Mexico. I can’t stand to be in a country that is more Surrealist than my paintings.” Though Breton included Mexico’s own Frida Kahlo and her husband Diego Rivera in the fourth International Surrealist Exhibition of 1940's Mexico City, Kahlo never embraced the movement.

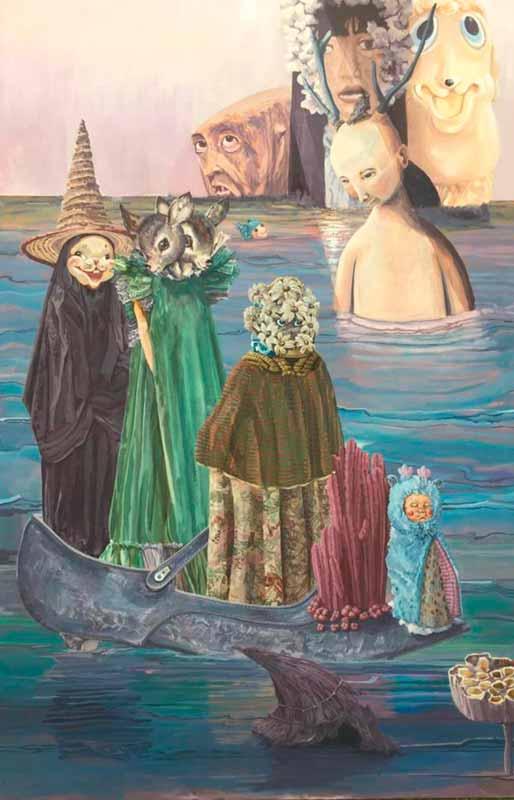

Among those immigrants to Mexico were three artists eventually nicknamed "The Three Witches." They were Leonora Carrington of England, Remedios Varo from Spain, and Hungarian-born photographer Kati Horna. While Carrington and Varo both rejected the Surrealist label, they shared an interest in mysticism and magic, amply provided by Mexican culture.

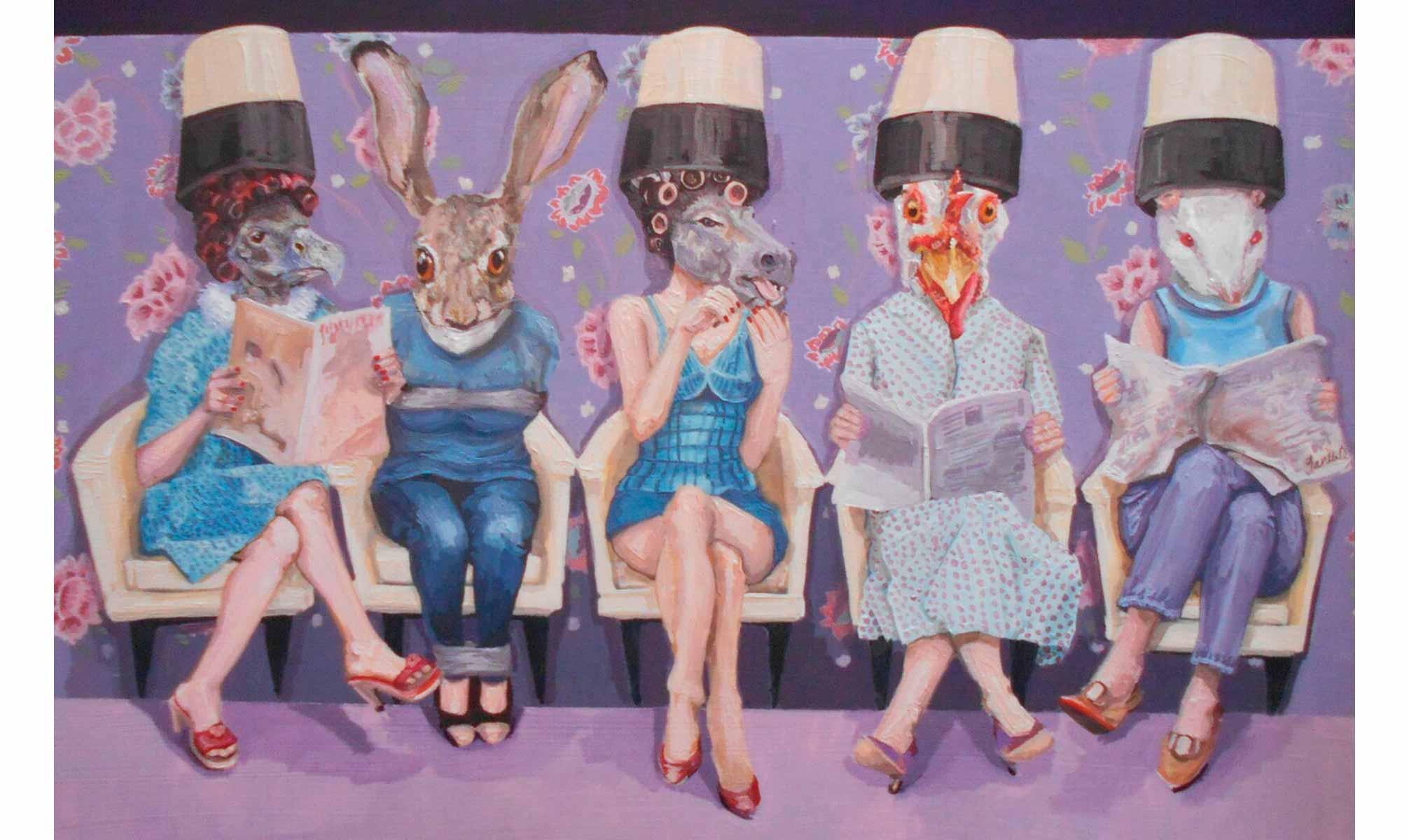

Liminal spaces and practices still exist. Using techniques including herbalism, divination, and spiritual cleansing, traditional curanderismo healers treat ailments including soul loss and the evil eye. A brujo can inflict a curse, while shape-shifting sorcerers called nahualli take animal forms.