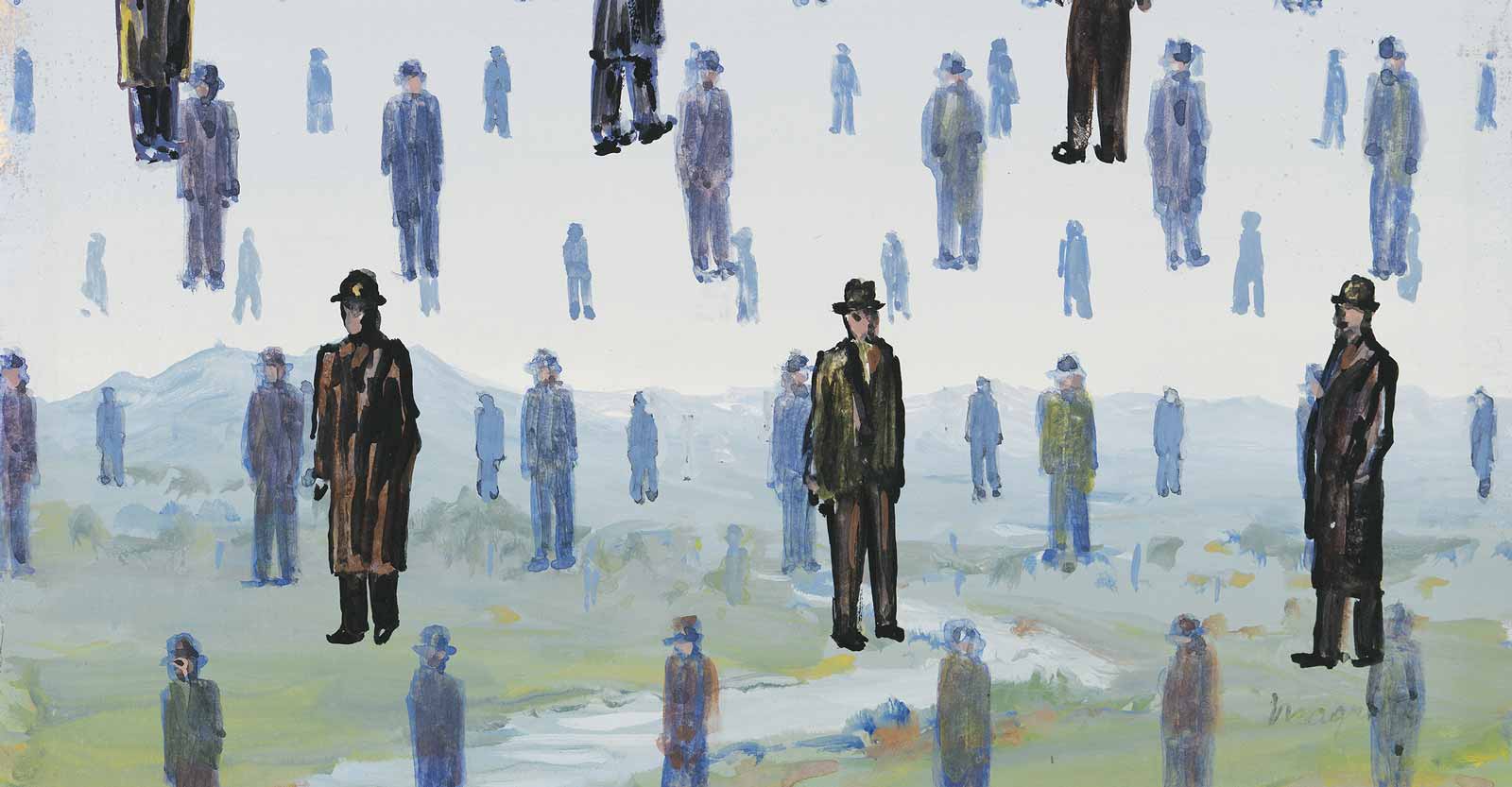

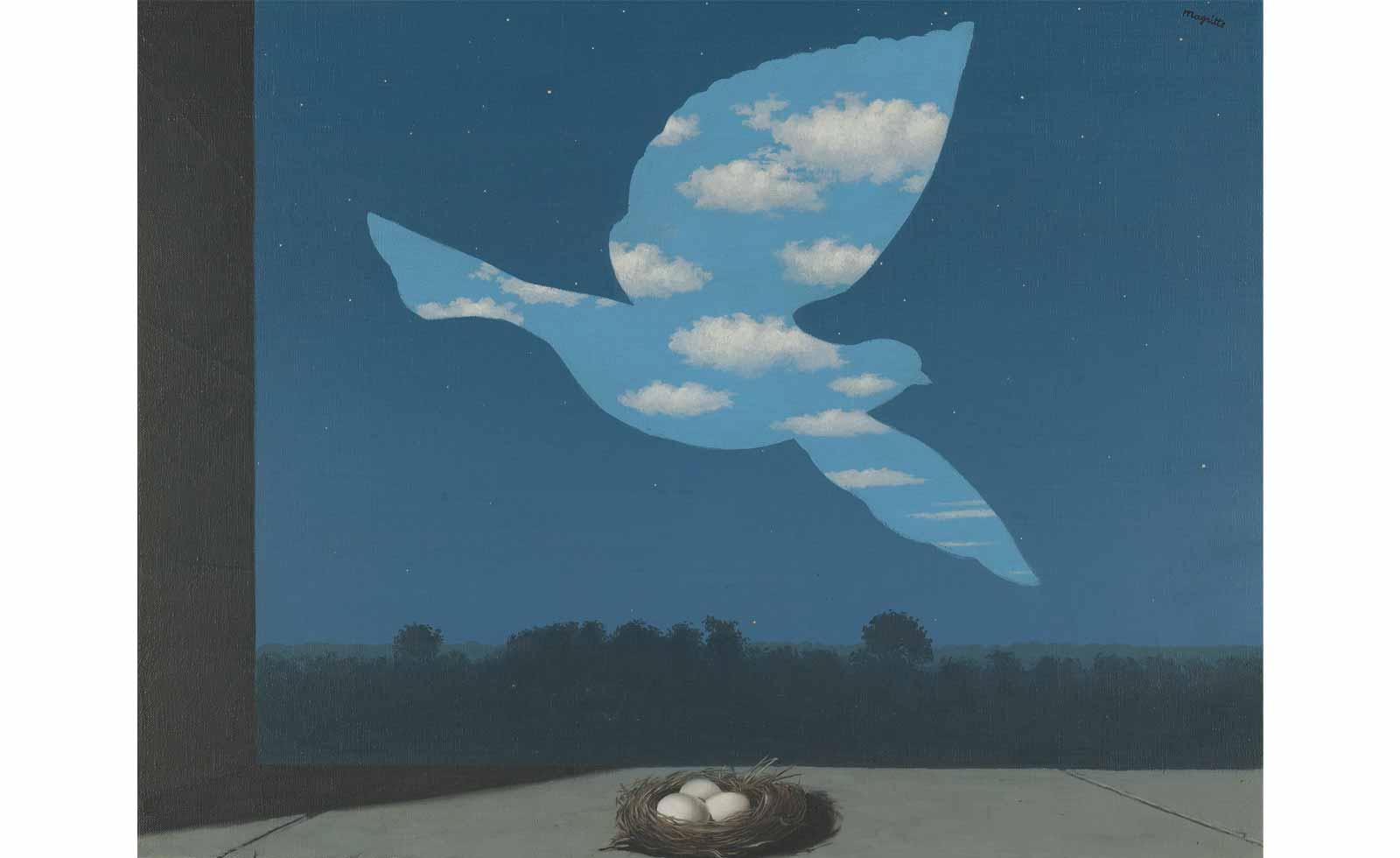

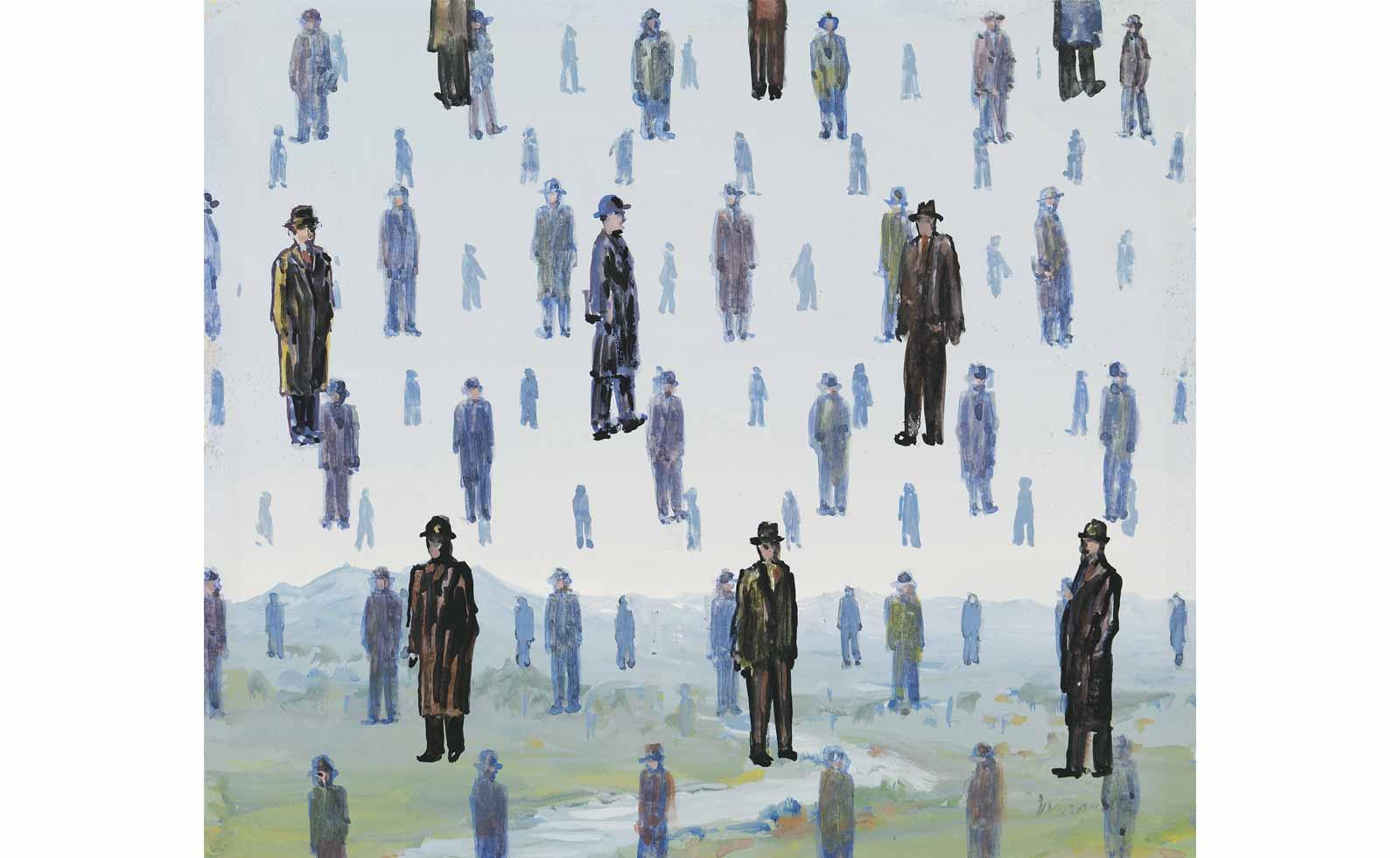

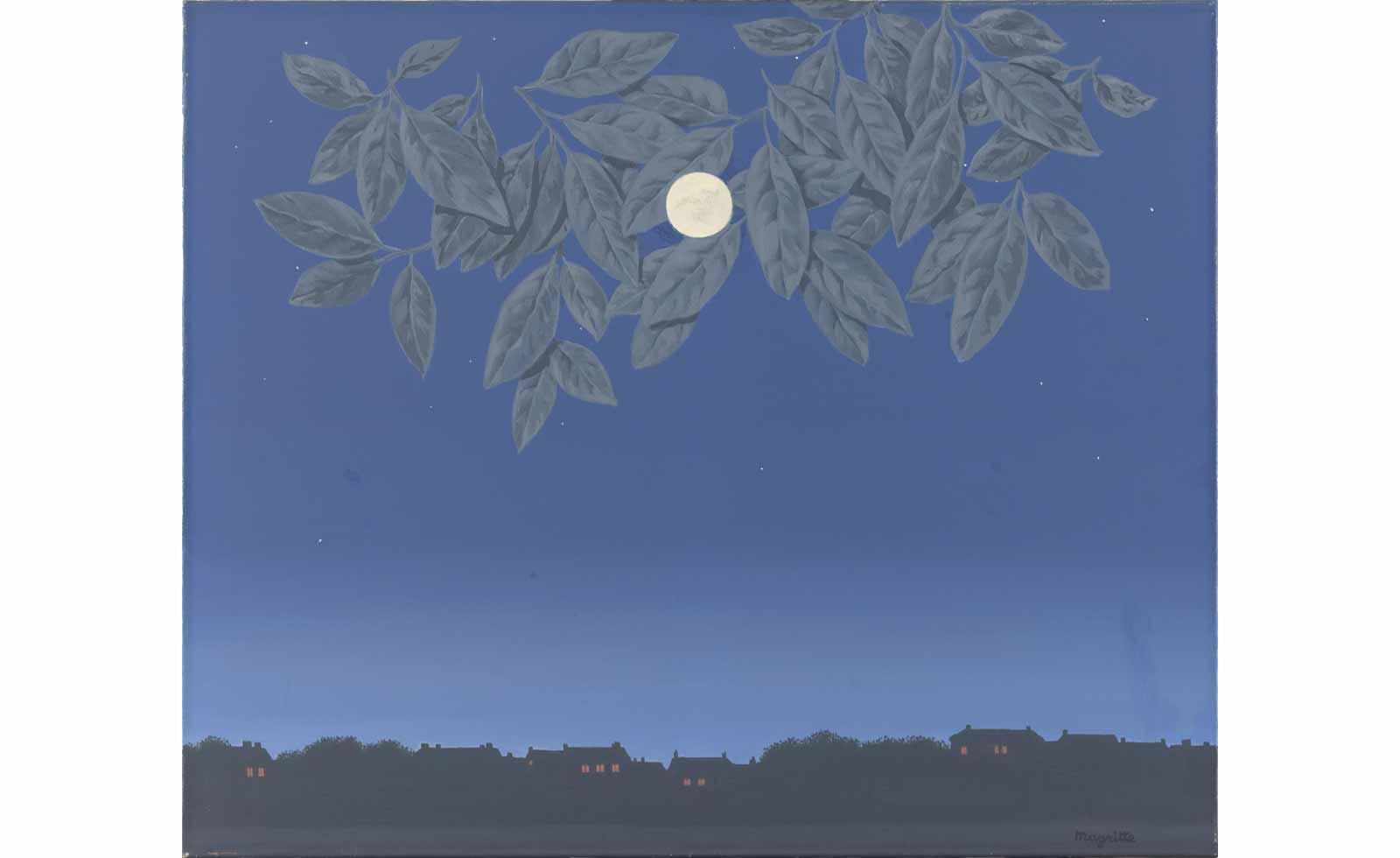

The consummate Surrealist painter, René Magritte (1898–1967) is widely celebrated for his amusing, thought-provoking images featuring ordinary objects represented in extraordinary settings. Distinguishable for his uncanny use of clouds, pipes, bowler hats, apples, and nudes, his paintings influenced subsequent generations of pop and conceptual artists and—perhaps more notably—the world of advertising, which is where his own illustrious career began.

Born in Belgium to a businessman father and a milliner mother, he received weekly painting lessons from age twelve and at seventeen started studying fine art at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, while simultaneously taking classes in the decorative and graphic arts there, too. In an interview shortly before his death, he claimed to have polished his drawing skills in the school’s classes on flora and fauna, where he also acquired his skills in anatomy and perspective, which helped make his pictures seem more real.

Magritte showed his early work—initially created in the style of the Impressionists before morphing into a blend of Cubism and Futurism—in local salon presentations and avant-garde publications. The artist’s first means of survival, however, came not from his personal paintings and drawings but from design work drawing decorative objects for wallpapers and through commissions for advertisements and catalogs. Designing posters and brochures for chocolate makers, car manufacturers, fashion houses, music publishers, and the cinema and theatre, Magritte was able to explore media and aesthetic styles, while sustaining a living and developing his painting skills and ideas on the side.

Inspired by the discovery of a dreamlike juxtaposition of objects and surroundings in the paintings of Giorgio de Chirico, who had a significant impact on the Surrealist movement, and Max Ernst’s innovative use of collage to construct strange new narratives, Magritte established a signature style of figurative painting, which Ernst later described as “collages painted entirely by hand.”