While some institutions have been slow to adapt to the tsunami of evidence that women have been the makers of many of the most brilliantly executed works throughout history, the Baltimore Museum of Art (“BMA”) has been a trailblazer. In its “2020 Vision” initiative, the museum dedicated its entire 2020 calendar year of exhibitions, programs, and acquisitions to artwork by women-identifying artists to coincide with the centennial of women’s suffrage in the United States. That year, the BMA spent close to $3 million to acquire work by 49 women artists, including works by Betye Saar, Margaret Taylor-Burroughs, Cherokee artist Kay WalkingStick, and a monumental map painting by Salish artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, who had her first New York retrospective at the Whitney Museum this past summer. In January 2023 the BMA appointed Asma Naeem as its new director. She is the first woman of color to lead the institution.

‘Making Her Mark’ Explores Four Centuries of Groundbreaking Women Artists in Europe

Anne Gueret, Portrait of a Female Artist with a Portfolio (Self-Portrait?), 1793.

The Baltimore Museum Presents a Show to Correct the Canon

Judith Leyster, Self-portrait, 1633.

Showcasing the accomplishments of European women artists, this exhibition seeks to make visible historically undervalued women who produced across media in traditional high-art categories.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith and her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes, 1623-25.

Now, the BMA, in collaboration with the Art Gallery of Ontario, has launched Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400-1800. Showcasing the accomplishments of European women artists, this exhibition seeks to make visible historically undervalued women who produced across media in traditional high-art categories—including painting, drawing, printmaking, sculpture, and the decorative arts—as well as those labeled craft, comprising material culture, such as embroidery, paper-cutting, and lacemaking. Curated by Andaleeb Badiee Banta, Senior Curator and Department Head, Prints, Drawings & Photographs at the BMA, and Alexa Greist, Associate Curator and R. Fraser Elliott Chair, Prints & Drawings at Art Gallery of Ontario, this effort demonstrates the BMA’s commitment to correcting women’s place in the canon of art history and engaging other international institutions to join them in that endeavor.

"Collaboration has been at the heart of the Making Her Mark project,” Badiee Banta told Art & Object over email. “Addressing women's diverse modes of making across four centuries required expertise far beyond that of one person's. From the beginning, my co-curator and I were eager to consult with a broad range of scholars and museum professionals to learn from their experiences and research. In fact, we soon realized that our collaborative model echoed the centrality of collaboration in the production of European art of the past. For centuries, women have been making art together in communal and corporate settings like convents, workshops, and the home. The notion of singular artistic genius is a decidedly male-established narrative."

The exhibition is thematically organized in four sections: Faith & Power, includes a view of the world usually dominated by male patronage. The Italian Baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1653) is the most high-profile female artist from that era to gain recent recognition. She is represented here by the powerful Judith and Her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes (c. 1623-25). Considered by many to be her most accomplished work, this is one of four paintings where Gentileschi depicts the biblical story of Judith murdering the general Holofernes with a Caravaggesque use of light and shade.

The section on Interiority engages the quiet intimacy of domestic labor, interior decoration, and the arts of calligraphy, drawing, and embroidery. Lush still life paintings by Anne Vallayer-Coster (1744-1818), who was a precocious young talent, and prolific Baroque painter Josefa de Ayala (1630-1684) are bursting with life. An 18th-century wooden cabinet with paper filigree and hairwork panels by Mary Anne Harvey Bonnell (1763-1853) is a recent acquisition. It is one of only six surviving examples of furniture in this medium and the BMA’s first pre-20th-century piece of furniture by named women makers.

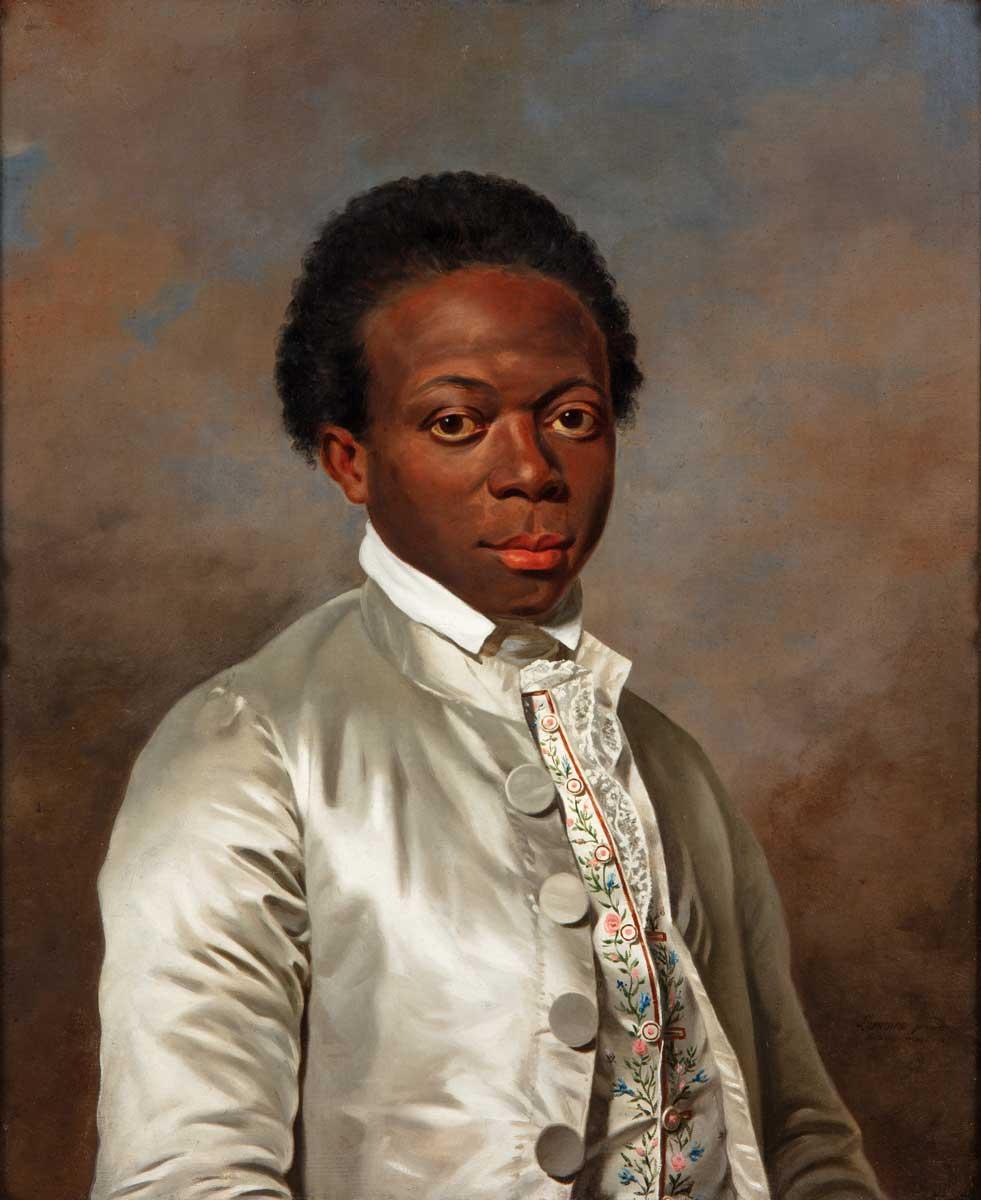

Marie Victoire Lemoine, Portrait of a Youth in an Embroidered Vest, 1785.

The gallery focusing on The Scientific Impulse showcases both professional and amateur naturalist drawings and paintings of flora and fauna. Science was, and to a certain extent still is, a field dominated by men. The abundance of work revealed by women includes Pauline Rifer de Courcelles (Madame Knip) (1781-1851) who focused on detailed drawings of birds, which decorated elegant sets of porcelain. Delicate watercolors by Giovanna Garzoni (1600-1670) belie the influence of Artemisia Gentileschi who Garzoni is thought to have interacted with. The Dutch still-life painter Rachel Ruysch (1664-1750) specialized in flowers and had a successful career in her own lifetime. She is the most well-documented female painter of the Dutch Golden Age and as a result her name has increasingly appeared at art auctions today. These women artists’ ability to observe and record natural phenomena brought to Europe via trade and the push to colonize far flung empires, also includes women’s involvement in the medical and astronomical sciences via more ephemeral media, paper documents, and manuscripts.

Women’s roles in the business of arts production, promotion, and education are uncovered in The Entrepreneurial Spirit. For women artists in any age, but particularly during this time frame, a self-portrait was a political act. The bold, exquisite self-portrait by Judith Leyster (1609-1660) now in the collection of the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., was first mistakenly attributed to Frans Hals. It was only correctly identified as a painting by Leyster in 1949. In this superbly clever work, she is self-confident about her talent and is showing off by painting herself in a huge lace collar and silk sleeves which would have been extremely expensive and probably her best clothes. The classicist French portrait painter Marie Victoire Lemoine (French, 1754 - 1820) was known for her detailed miniatures. Her dignified, striking portrait of a Black Youth in an Embroidered Vest 1785 demonstrates her ability to render the deep skin-tone of her subject in contrast to the white satin jacket he wears. The elaborate porcelain tea service by Marie-Victoire Jaquotot (1772-1855) features portraits of famous women, queens and princesses, and made me think about Judy Chicago’s 1979 installation, The Dinner Party.

A wonderful compliment to the BMA exhibition is Katy Hessel’s 2022 book The Story of Art Without Men. Hessel’s book is a much-needed correction to the status quo given that the two most widely referenced art history books, The Story of Art by E.H. Gombrich, first published in 1950, and H.W. Janson’s The History of Art, first published in 1962 (and the text this author used in college in the 1960s), did not include a single female artist in their original printing. Although subsequent editions of these male dominated texts have added a few women, much work still needs to be done.

In her Great Women Artists podcast, Hessel asks, “Was it a conscious decision to write women out of art history?” We can only conclude the answer, on some level, is “yes.” In a PBS interview coinciding with the publication of her book Hessel declares, “Women artists are not a trend.” She challenges museums to, “Bring the one percent of art by women out of storage and show it.” Hessel is not shy about declaring her goal to alter the path of art history. She is working hard to build a legacy for future generations very different than the story about art that was told to the talented women featured in Making Her Mark. Today, Hessel echoes the challenge boldly stated by Artemisia Gentileschi in 1649, “I’ll show you what a woman can do!”

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston has mounted a show of women artists with a narrower focus. Strong Women in Renaissance Italy, which is currently on view, and this month will see the reopening of the National Museum of Women in the Arts, in Washington, D.C., making this fall an unprecedented season of riches for women artists.

Making Her Mark. is co-organized by the Baltimore Museum of Art and the Art Gallery of Ontario. Co-curated by Andaleeb Badiee Banta, Senior Curator and Department Head, Prints, Drawings & Photographs at the BMA, and Alexa Greist, Curator and R. Fraser Elliott Chair, Prints & Drawings at the AGO.